Terence Corcoran: John Kenneth Galbraith's industrial state makes a comeback

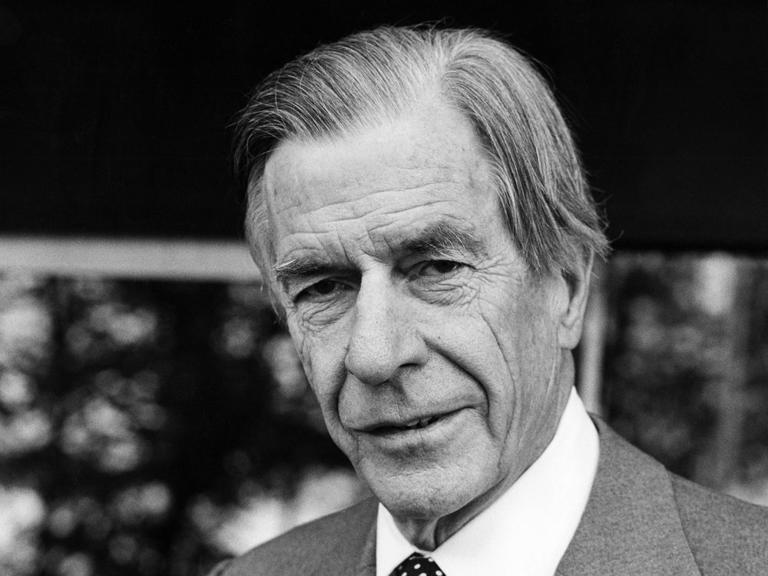

Economist John Kenneth Galbraith, 1978.© Provided by Financial Post

It is hardly news that national industrial policy is making a big comeback around the world, almost 60 years after John Kenneth Galbraith wrote The New Industrial State, a 1967 bestseller that proposed replacing market economics with state industrial planning. His theories failed to take hold in the 20th century but we are now driving into the 21st century under the influence of Galbraith’s neo-Marxist economic views.

Recent reports include a column in the Financial Times which complained this week that while America under President Joe Biden has rolled out a plethora of tariffs, subsidies and regulations, the plan falls shamefully short of meeting the full official industrial policy status. For that to happen, America needs to move away from “the mythology of efficient and always self-correcting markets, to an age in which the public sector will have to do more nudging, or ‘marketcrafting’, as some would put it, to ensure economically and politically stable outcomes.”

Throughout the European Union, politicians and activists are constantly insisting on more state actions to bring in the green new deal and industrial development. EU government leaders are agitating for a more “proactive innovative industrial strategy” to fight off competition from China, France’s economic minister said last year.

In North America, industrial policy theory crashed in the 1980s as one economic camp after another shot it down as unworkable. Both Democrats and Republicans turned against massive state planning in the United States. Various efforts were launched in Canada, nationally and provincially, but the economy has remained largely market driven.

In Quebec, a new study from The Centre for Productivity and Prosperity concludes that 25 years of provincial government industrial policy “has been a failure.” One of the study’s authors describes the basic industrial policy problem: “The government actively promotes the development of sectors it deems promising and passively seeks to preserve jobs in businesses that are not conducive to productivity, innovation, and investment.”

The root of the industrial strategy problem is the impossible task of predicting and controlling future economic developments in co-operation with businesses looking for state backing, known in economics as corporate rent-seekers. In the Quebec case, the researchers unfortunately do not totally reject the industrial planning as a method. They simply seem to be saying that the Quebec state got it wrong and needs to make it right. They call on the government to “urgently conduct a complete and uncompromising diagnosis” of the failed policies.

Another new study released this week looked at a classic industrial strategy story, Japan’s 1980s effort to boost technology development with policies similar to Biden’s CHIPs plan to create regional tech hubs. The study concludes that while Japan boosted the fortunes of some corporations and regions, the benefits were not widely distributed.

The latest Canadian formulation of industrial policy-making has triggered a relatively fierce debate over the role Canada’s pension funds should play in financing Canadian industry. A group of 90 corporate executives published an open letter calling on Ottawa to change pension investment rules to force pension managers to invest more money in Canadian corporations. “Government has the right, responsibility, and obligation to regulate how this savings regime operates,“ said Canada’s top corporate leaders.

The rent-seeking aspect of the executive plea was identified in an incisive report on the pension issue by the Financial Post’s Barbara Shecter. One pension fund manager noted the “self-serving” executive plea for a structure that would effectively direct pension investment funds into Canadian corporate shares. Also, forcing pensions to invest more in Canadian corporations would expose pension funds unstable industrial policies.

Specifics for directing pension funds are expected in next month’s budget. Will the government actually move in directions that have been strongly denounced throughout the pension industry? One determining factor will be the Trudeau government’s willingness to push Canada’s public pensions into funding the massive regulatory and subsidy policies around green growth. Does that mean pensions, already supportive of net-zero targets, could soon be forced to invest in Canadian electric vehicles and critical mineral developments?

It is not a coincidence that John Kenneth Galbraith’s 1967 magnum opus puts new technical developments at the top of his justifications for a new industrial state. When investment in technological development is running high, he said, there is the risk that “a failure in persuading consumers to buy the product can be extremely expensive.” To get around the reluctant consumer, Galbraith called for industrial policy. “The cost and associated risk can be greatly reduced if the state pays for more exalted technical development or guarantees a market for the technologically advanced product. Suitable justification — national defence, national prestige, deeply felt public need such as for supersonic travel — can be found. Modern technology thus defines a growing function of the modern state.”

Substituting EVs and net-zero for supersonic travel puts us squarely in the 21st-century version of Galbraith’s industrial policy thought process. Even supersonic travel is back on the planning agenda . A news story this week reports that NASA and a collection of corporations are developing jets that will break the sound barrier “with smaller carbon footprint, mostly because they will be fuelled by sustainable aviation fuel.”

Get out the planning books! We are flying into the new industrial state at record speed.

• Email: tcorcoran@postmedia.com

Financial Post