Glass half empty? What climate change means for Canada's wine industry

Wine has long been synonymous with good times, celebration and an appreciation of the finer things in life

Evolved over thousands of years and cultures, wine is something we all take for granted. But that is all about to change.

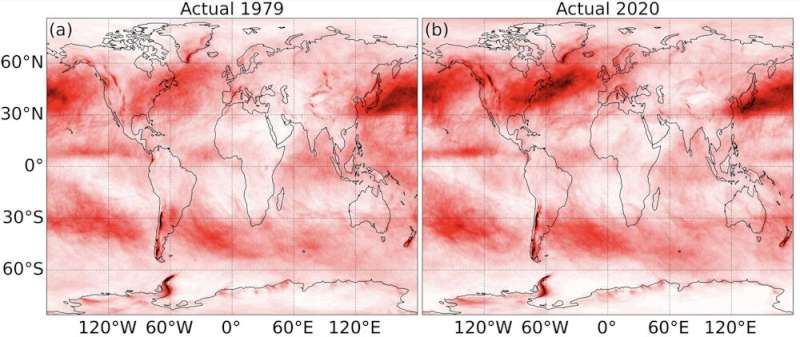

Recent publications on climate volatility have painted a bleak picture of the future for this beloved alcoholic beverage.

It is now clear that global warming is affecting most of the crops that are essential to feed the world. Climate change is impacting the production of both staple food crops like wheat, rice and corn and also commodity crops including coffee, cocoa and grapes.

Most of the world's vineyards, including its most venerable names, are facing incredible existential challenges that pose essential risks to their very survival if they don't adapt to the changing environmental conditions. Canadian wine is by no means exempt from these changes.

Signs of things to come

In January 2024, the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia experienced a devastating cold snap, with temperatures plummeting below -20°C. This unprecedented climatic event inflicted severe damage to all the grapevines in the region and could result in a 97% to 99% decrease in annual grape and wine production across the region—with projected revenue losses over the next few years in the $440 to $445 million range.

It is still too early in the season to assess the full extent of the damage and, while many vines will need replacement, there is still hope that with careful management some vines will bounce back within a few years.

The Okanagan cold snap is merely the latest climate change-induced climatic event to rock the Canadian and global wine industry in recent years.

Drought conditions, heat waves and smoke from forest fires have heavily impacted grape yields and resulted in variations in wine quality across regions. The cumulative effect of these climate-related events underscores the undeniable influence that climate change is already having on wine production and quality.

The viticulture industry must confront and adapt to these challenges to ensure its sustainability and resilience in the face of ongoing environmental changes.

The future of wineries

In order to adapt, the wine industry will need to embrace new production methods and technologies while promoting collaboration between researchers and growers.

Agriculture technologies—ranging from precision viticulture tools to high-resolution spatial information and AI—offer invaluable insights into vineyard management, grape quality optimization and environmental practices.

Providing more support to viticulturists can help incentivize sustainable farming practices and eco-labeling. At the same time, providing access to resources and education can significantly enhance the industry's resilience and sustainability over the long term.

Meanwhile, forward-thinking new policies could encourage research and development in areas like climate change adaptation, disease management and alternative grape varieties more suitable for changing environmental conditions. Policymakers should promote the adoption of renewable energy sources and more climate-resilient approaches to the vines and the soil.

Canadian governments should provide financial incentives and support the wine industry's transition to a more sustainable future. The recently announced $177 million, three-year extension to the federal government's Wine Sector Support Program is a good start.

Climate change not entirely to blame

Grapevines are often cultivated in areas that are incredibly vulnerable to changes in climate and while global warming is the greatest challenge the wine industry faces, it is not the only one.

The last 20 years have seen a significant drop in wine consumption as changing lifestyles, price hikes and health concerns push consumers—particularly young people—to cut back on alcohol. When people do indulge in wine, they are increasingly splurging on pricier bottles, choosing quality over quantity.

Data shows that Gen Z is sipping far less alcohol (around 20% less) than previous generations and more young people than ever are jumping on the no or low alcohol "NoLo" movement.

China, long a major wine market, has so far seen a 25% drop in wine sales in 2024 as rising prices and economic slowdown has left fewer glasses clinking than ever. Simply put, the wine world is experiencing a sobering moment.

Turning challenge into opportunity

Wine is one of life's great pleasures and an intrinsic part of human cultures—likely almost as old as civilization itself.

For those of us who drink wine, it is imperative that we try to be mindful of how we can all support our local viticulture industry in these challenging times.

As consumers, our role is pivotal in supporting resilience. Actions ranging from embracing local products, visiting vineyards, buying new wines crafted from climate-resilient varieties and staying informed about the challenges confronting the winery sector all can contribute to a brighter future for the industry.

We need to believe that the Canadian wine industry can not only adapt to change but can also thrive by producing great wines and developing the wine tourism that will educate consumers about the tradition and cultural heritage of Canadian wine making.

While global warming news can often seem all doom-and-gloom there remains a ray of hope. Using adaptation strategies and embracing agritech innovation, we can mitigate the impacts of climate change as much as possible. This adversity could catalyze a heightened focus on sustainability, adaptation and innovation within the viticulture sector. That, if nothing else, would be a positive outcome.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bordeaux for Kent, climate change to shift wine regions: Study