by Talia Ogliore, Washington University in St. Louis

American bison at the Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in Oklahoma.

Credit: Natalie Mueller

Blame it on the bison.

If not for the wooly, boulder-sized beasts that once roamed North America in vast herds, ancient people might have looked past the little barley that grew under those thundering hooves. But the people soon came to rely on little barley and other small-seeded native plants as staple food.

New research from Washington University in St. Louis helps flesh out the origin story for the so-called "lost crops." These plants may have fed as many Indigenous people as maize, but until the 1930s had been lost to history.

As early as 6,000 years ago, people in the American Northeast and Midwest were using fire to maintain the prairies where bison thrived. When Europeans slaughtered the bison to near-extinction, the plants that relied on these animals to disperse their seeds began to diminish as well.

"Prairies have been ignored as possible sites for plant domestication, largely because the disturbed, biodiverse tallgrass prairies created by bison have only been recreated in the past three decades after a century of extinction," said Natalie Mueller, assistant professor of archaeology in Arts & Sciences.

Following the bison

In a new publication in The Anthropocene Review, Mueller reports on four field visits during 2019 to the Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in eastern Oklahoma, the largest protected remnant of tallgrass prairie left on Earth. The roughly 40,000-acre preserve is home to about 2,500 bison today.

Mueller waded into the bison wallows after years of attempting to grow the lost crops from wild-collected seed in her own experimental gardens.

"One of the great unsolved mysteries about the origins of agriculture is why people chose to spend so much time and energy cultivating plants with tiny, unappetizing seeds in a world full of juicy fruits, savory nuts and plump roots," Mueller said.

They may have gotten their ideas from following bison.

Anthropologists have struggled to understand why ancient foragers chose to harvest plants that seemingly offer such a low return on labor.

"Before any mutualistic relationship could begin, people had to encounter stands of seed-bearing annual plants dense and homogeneous enough to spark the idea of harvesting seed for food," Mueller said.

Recent reintroductions of bison to tallgrass prairies offer some clues.

For the first time, scientists like Mueller are able to study the effects of grazing on prairie ecosystems. Turns out that munching bison create the kind of disturbance that opens up ideal habitats for annual forbs and grasses—including the crop progenitors that Mueller studies.

Credit: Washington University in St. Louis

Harvesting at the wallow's edge

At the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, Mueller and her team members got some tips from local expert Mike Palmer.

"Mike let us know roughly where on the prairie to look for the bison," Mueller said. "His occurrence data were at the resolution of roughly a square mile, but that helps when you're on a 60-square-mile grassland.

"I thought it would be hard to find trails to follow before I went out there, but it's not," she said. "They are super easy to find and easy to follow, so much so that I can't imagine humans moving through a prairie any other way!"

Telltale signs of grazing and trampling marked the "traces" that bison make through shoulder-high grasses. By following recently trodden paths through the prairie, the scientists were able to harvest seeds from continuous stands of little barley and maygrass during their June visit, and sumpweed in October.

"While much more limited in distribution, we also observed a species of Polygonum closely related to the crop progenitor and wild sunflowers in bison wallows and did not encounter either of these species in the ungrazed areas," Mueller said.

It was easier to move through the prairie on the bison paths than to venture off them.

"The ungrazed prairie felt treacherous because of the risk of stepping into burrows or onto snakes," she said.

With few landscape features for miles in any direction, the parts of the prairie that were not touched by bison could seem disorienting.

"These observations support a scenario in which ancient people would have moved through the prairie along traces, where they existed," Mueller said. "If they did so, they certainly would have encountered dense stands of the same plant species they eventually domesticated."

Diverse landscapes

Mueller encourages others to consider the role of bison as 'co-creators'—along with Indigenous peoples—of landscapes of disturbance that gave rise to greater diversity and more agricultural opportunities.

"Indigenous people in the Midcontinent created resilient and biodiverse landscapes rich in foods for people," she said. "They managed floodplain ecosystems rather than using levees and dams to convert them to monocultures. They used fire and multispecies interactions to create mosaic prairie-savanna-woodland landscapes that provided a variety of resources on a local scale."

Mueller is now growing seeds that she harvested from plants at the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve and also seeds that she separated from bison dung from the preserve. In future years, Mueller plans to return to the preserve and also to visit other prairies in order to quantify the distribution and abundance of crop progenitors under different management regimes.

"These huge prairies would not have existed if the native Americans were not maintaining them," using fire and other means, Mueller said. But to what end? Archaeologists have not found caches of bones or other evidence to indicate that Indigenous people were eating lots of prairie animals. Perhaps the ecosystems created by bison and anthropogenic fire benefited the lost crops.

"We don't think of the plants they were eating as prairie plants," she said. "However, this research suggests that they actually are prairie plants—but they only occur on prairies if there are bison.

"I think we're just beginning to understand what the botanical record was telling us," Mueller said. "People were getting a lot more food from the prairie than we thought."

Explore further

Five facts about bison, the new US national mammal

Blame it on the bison.

If not for the wooly, boulder-sized beasts that once roamed North America in vast herds, ancient people might have looked past the little barley that grew under those thundering hooves. But the people soon came to rely on little barley and other small-seeded native plants as staple food.

New research from Washington University in St. Louis helps flesh out the origin story for the so-called "lost crops." These plants may have fed as many Indigenous people as maize, but until the 1930s had been lost to history.

As early as 6,000 years ago, people in the American Northeast and Midwest were using fire to maintain the prairies where bison thrived. When Europeans slaughtered the bison to near-extinction, the plants that relied on these animals to disperse their seeds began to diminish as well.

"Prairies have been ignored as possible sites for plant domestication, largely because the disturbed, biodiverse tallgrass prairies created by bison have only been recreated in the past three decades after a century of extinction," said Natalie Mueller, assistant professor of archaeology in Arts & Sciences.

Following the bison

In a new publication in The Anthropocene Review, Mueller reports on four field visits during 2019 to the Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in eastern Oklahoma, the largest protected remnant of tallgrass prairie left on Earth. The roughly 40,000-acre preserve is home to about 2,500 bison today.

Mueller waded into the bison wallows after years of attempting to grow the lost crops from wild-collected seed in her own experimental gardens.

"One of the great unsolved mysteries about the origins of agriculture is why people chose to spend so much time and energy cultivating plants with tiny, unappetizing seeds in a world full of juicy fruits, savory nuts and plump roots," Mueller said.

They may have gotten their ideas from following bison.

Anthropologists have struggled to understand why ancient foragers chose to harvest plants that seemingly offer such a low return on labor.

"Before any mutualistic relationship could begin, people had to encounter stands of seed-bearing annual plants dense and homogeneous enough to spark the idea of harvesting seed for food," Mueller said.

Recent reintroductions of bison to tallgrass prairies offer some clues.

For the first time, scientists like Mueller are able to study the effects of grazing on prairie ecosystems. Turns out that munching bison create the kind of disturbance that opens up ideal habitats for annual forbs and grasses—including the crop progenitors that Mueller studies.

Credit: Washington University in St. Louis

Harvesting at the wallow's edge

At the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, Mueller and her team members got some tips from local expert Mike Palmer.

"Mike let us know roughly where on the prairie to look for the bison," Mueller said. "His occurrence data were at the resolution of roughly a square mile, but that helps when you're on a 60-square-mile grassland.

"I thought it would be hard to find trails to follow before I went out there, but it's not," she said. "They are super easy to find and easy to follow, so much so that I can't imagine humans moving through a prairie any other way!"

Telltale signs of grazing and trampling marked the "traces" that bison make through shoulder-high grasses. By following recently trodden paths through the prairie, the scientists were able to harvest seeds from continuous stands of little barley and maygrass during their June visit, and sumpweed in October.

"While much more limited in distribution, we also observed a species of Polygonum closely related to the crop progenitor and wild sunflowers in bison wallows and did not encounter either of these species in the ungrazed areas," Mueller said.

It was easier to move through the prairie on the bison paths than to venture off them.

"The ungrazed prairie felt treacherous because of the risk of stepping into burrows or onto snakes," she said.

With few landscape features for miles in any direction, the parts of the prairie that were not touched by bison could seem disorienting.

"These observations support a scenario in which ancient people would have moved through the prairie along traces, where they existed," Mueller said. "If they did so, they certainly would have encountered dense stands of the same plant species they eventually domesticated."

Diverse landscapes

Mueller encourages others to consider the role of bison as 'co-creators'—along with Indigenous peoples—of landscapes of disturbance that gave rise to greater diversity and more agricultural opportunities.

"Indigenous people in the Midcontinent created resilient and biodiverse landscapes rich in foods for people," she said. "They managed floodplain ecosystems rather than using levees and dams to convert them to monocultures. They used fire and multispecies interactions to create mosaic prairie-savanna-woodland landscapes that provided a variety of resources on a local scale."

Mueller is now growing seeds that she harvested from plants at the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve and also seeds that she separated from bison dung from the preserve. In future years, Mueller plans to return to the preserve and also to visit other prairies in order to quantify the distribution and abundance of crop progenitors under different management regimes.

"These huge prairies would not have existed if the native Americans were not maintaining them," using fire and other means, Mueller said. But to what end? Archaeologists have not found caches of bones or other evidence to indicate that Indigenous people were eating lots of prairie animals. Perhaps the ecosystems created by bison and anthropogenic fire benefited the lost crops.

"We don't think of the plants they were eating as prairie plants," she said. "However, this research suggests that they actually are prairie plants—but they only occur on prairies if there are bison.

"I think we're just beginning to understand what the botanical record was telling us," Mueller said. "People were getting a lot more food from the prairie than we thought."

Explore further

Five facts about bison, the new US national mammal

More information: Natalie G Mueller et al. Bison, anthropogenic fire, and the origins of agriculture in eastern North America, The Anthropocene Review (2020).

Provided by Washington University in St. Louis

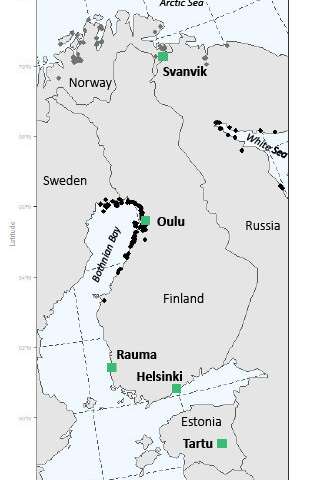

Five botanical gardens in which Siberian primroses from Norway and Finland were planted. Credit: University of Helsinki

Five botanical gardens in which Siberian primroses from Norway and Finland were planted. Credit: University of Helsinki