Scientists investigate potential regolith origin on Uranus' moon Miranda

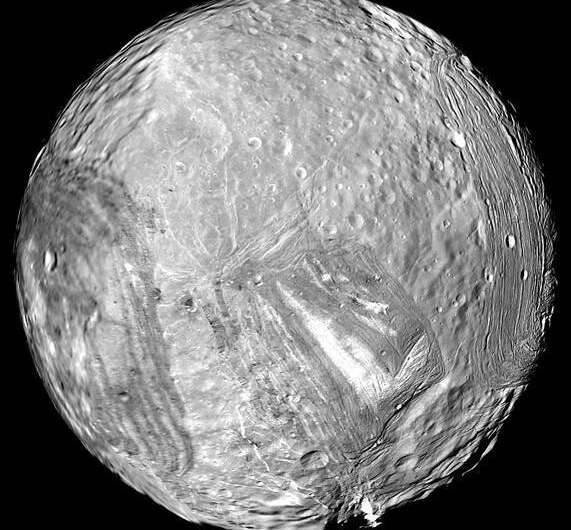

In a recent study published in The Planetary Science Journal, a pair of researchers led by The Carl Sagan Center at the SETI Institute in California investigated the potential origin for the thick regolith deposits on Uranus' moon, Miranda. The purpose of this study was to determine Miranda's internal structure, most notably its interior heat, which could help determine if Miranda harbors—or ever harbored—an internal ocean.

"It is unlikely that Miranda would be able to retain a subsurface ocean to the present day due to its small size," said Dr. Chloe Beddingfield, who is a scientist at the NASA Ames Research Center. "However, a thick regolith layer would act like an insulating blanket, trapping heat inside Miranda and enhancing the longevity of a subsurface ocean for some period. This trapped heat would have also promoted endogenic activity for longer periods of time on Miranda, such as the geologic activity that formed one or more of Miranda's coronae or the global rift system."

Regolith is defined as "a region of loose unconsolidated rock and dust that sits atop a layer of bedrock," and the surface material on both the moon and Mars are frequently referred to as regolith as opposed to soil much like Earth. The difference being that soil provides necessary nutrients and minerals for things to grow, whereas regolith can be considered dead soil.

For the study, the researchers analyzed craters, specifically "muted" craters, to determine the thickness of Miranda's surface regolith. These analyses included measuring the crater depth-diameter ratios, crater size-frequency distribution—also known as "crater counting," and the central mound within a specific crater, Alonso Crater. The study's findings determined three potential sources for Miranda's thick regolith, which include giant impact ejecta, plume deposits, and ring deposits from Uranus itself. The researchers state they favor the ring deposit hypothesis due to Miranda's blue color, and its regolith's large spatial extent and large thickness.

"If material from Uranus' rings were the primary source of Miranda's regolith, then that may indicate that Miranda formed out of ring material and/or that Miranda migrated through the rings in its early history," said Dr. Beddingfield. "In these scenarios, Uranus' rings may have been thicker in the past. However, future modeling work is needed to investigate these possibilities further."

Miranda was first discovered on February 16, 1948, by Gerard P. Kuiper at the McDonald Observatory in western Texas, and has only been visited by NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1986. This up-close encounter revealed a chaotic and intriguing world with craters, valleys, and chasms across its surface, with scientists continuing to debate to this day the processes behind the small moon's interesting features. One such type of feature is known as "coronae," which are large deformations that scientists hypothesize were formed from tectonic activity. So, how can this research help us better understand Miranda's overall surface appearance?

"Because Miranda's thick insulating regolith would reduce heat loss and possibly enhance geologic activity, the regolith may have helped support coronae formation," said Dr. Beddingfield. "The coronae are thought to have formed from upwelling diapirs that broke Miranda's surface. Perhaps the coronae inherited their polygonal shapes when those diapirs formed along pre-existing areas of weakness in the lithosphere, formed by pre-existing faults that make up global rift system. While the existence of Miranda's regolith doesn't tell us much about the specific processes involved in corona formation, it does allow us to get a sense of the relative timing of events and shows that geologic activity likely occurred over long periods of time."

The paper stresses that follow-up studies are required to better understand the potential possibilities other than Uranus ring deposits for Miranda's thick regolith.

"Miranda's regolith could be explained by processes other than ring material accumulation including material deposition due to plume activity in the past or deposition of ejecta from a giant impact," explained Dr. Beddingfield.

"We see evidence for thick plume deposits on Saturn's moon Enceladus, which exhibits ongoing plume activity. Alternatively, if one or more giant impact event events occurred during Miranda's early history, then the resulting ejecta may have formed the observed regolith on Miranda. While we favor the ring material deposition scenario, these two other scenarios are certainly feasible and warrant investigation in future work."

Currently, Voyager 2 remains the only spacecraft to have visited Uranus and its many moons, and there are no scheduled missions to revisit this far out in the solar system.

More information: Chloe B. Beddingfield et al, Miranda's Thick Regolith Indicates a Major Mantling Event from an Unknown Source, The Planetary Science Journal (2022). DOI: 10.3847/PSJ/ac9a4e

Journal information: The Planetary Science Journal

Provided by Universe Today Study reveals lunar regolith evolution process on Chang'e-4 landing area