By Michael Hudson

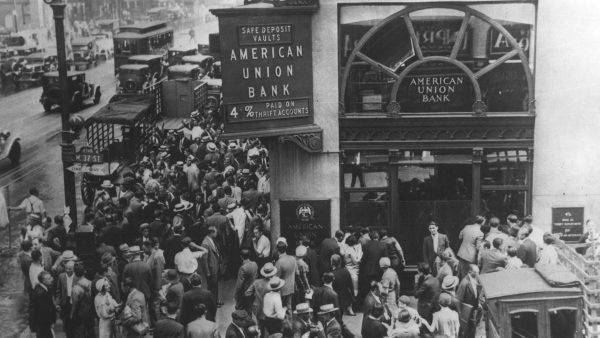

A run on American Union Bank in 1932

The California-based, cryptocurrency-focused Silvergate Bank collapsed on March 8. Two days later, Silicon Valley Bank went down as well, in the largest ever bank run. The latter was the second-biggest bank to fail in US history, and the most influential financial institution to crash since the 2008 crisis.

Economist Michael Hudson, co-host of the program Geopolitical Economy Hour, analyzes the disaster:

The breakup of banks that is now occurring in the United States is the inevitable result of the way in which the Obama administration bailed out the banks in 2008.

When real estate prices collapsed, the Federal Reserve flooded the financial system with 15 years of quantitative easing (QE) to re-inflate real estate prices – and with them, stock and bond prices.

What was inflated were asset prices, above all for the packaged mortgages that banks were holding, but also for stocks and bonds across the board. That is what bank credit does.

This made trillions of dollars for holders of financial assets – the One Percent and a bit more.

The economy polarized as stock prices recovered, the cost of home ownership soared (on low-interest mortgages), and the U.S. economy experienced the largest bond-market boom in history, as interest rates fell below 1%.

But in serving the financial sector, the Fed painted itself into a corner. What would happen when interest rates finally rose?

Rising interest rates cause bond prices to fall. And that is what has been happening under the Fed’s fight against “inflation,” by which it means rising wage levels.

Prices are plunging for bonds, and also for the capitalized value of packaged mortgages and other securities in which banks hold their assets against depositors.

The result today is similar to the situation that savings and loan associations (S&Ls) found themselves in the 1980s, leading to their demise.

S&Ls had made long-term mortgages at affordable interest rates. But in the wake of the Volcker inflation, the overall level of interest rates rose.

S&Ls could not pay higher their depositors higher rates, because their revenue from their mortgages was fixed at lower rates. So depositors withdrew their money.

To obtain the money to pay these depositors, S&Ls had to sell their mortgages. But the face value of these debts was lower, as a result of higher rates. The S&Ls (and many banks) owed money to depositors short-term, but were locked into long-term assets at falling prices.

Of course, S&L mortgages were much longer-term than was the case for commercial banks. And presumably, banks can turn over assets for the Fed’s line of credit.

But just as QE was followed to bolster the banks, its unwinding must have the reverse effect. And if it has made a bad derivatives trade, it’s in trouble.

Any bank has a problem of keeping its asset prices up with its deposit liabilities. When there is a crash in bond prices, the bank’s asset structure weakens. That is the corner into which the Fed has painted the economy.

Recognition of this problem led the Fed to avoid it for as long as it could. But when employment began to pick up and wages began to recover, the Fed could not resist fighting the usual class war against labor. And it has turned into a war against the banking system as well.

Silvergate was the first to go. It had sought to ride the cryptocurrency wave, by serving as a bank for various brand names.

After vast fraud by Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) was exposed, there was a run on cryptocurrencies. Their managers paid by withdrawing the deposits they had at the banks – above all, Silvergate. It went under. And with Silvergate went many cryptocurrency deposits.

The popular impression was that crypto provided an alternative to commercial banks and “fiat currency.” But what could crypto funds invest in to back their coin purchases, if not bank deposits and government securities or private stocks and bonds?

What was crypto, ultimately, if not simply a mutual fund with secrecy of ownership to protect money launderers?

Silvergate was a “special case,” given its specialized deposit base. Silicon Valley Bank also was a specialized case, lending to IT startups. First Republic Bank was specialized, too, lending to wealthy depositors in San Francisco and the northern California area.

All had seen the market price of their financial securities decline as Chairman Jerome Powell raised the Fed’s interest rates. And now, their deposits were being withdrawn, forcing them to sell securities at a loss.

Reuters reported on March 10 that bank reserves at the Fed were plunging. That hardly is surprising, as banks are paying about 0.2% on deposits, while depositors can withdraw their money to buy two-year U.S. Treasury notes yielding 3.8% or almost 4%. No wonder well-to-do investors are running from the banks.

This is the quandary in which banks – and behind them, the Fed – find themselves.

The obvious question is why the Fed doesn’t simply bail them out. The problem is that the falling prices for long-term bank assets in the face of short-term deposit liabilities now looks like the new normal.

The Fed can lend banks for their current short-fall, but how can solvency be resolved without sharply reducing interest rates to restore the 15-year, abnormal Zero Interest-Rate Policy (ZIRP)?

Interest yields spiked on March 10. As more workers were being hired than was expected, Mr. Powell announced that the Fed might have to raise interest rates even higher than he had warned. Volatility increased.

And with it came a source of turmoil that has reached vast magnitudes beyond what caused the 2008 crash of AIG and other speculators: derivatives.

JP Morgan Chase and other New York banks have tens of trillions of dollars worth of derivatives – that is, casino bets on which way interest rates, bond prices, stock prices, and other measures will change. For every winning guess, there is a loser.

When trillions of dollars are bet on, some bank trader is bound to wind up with a loss that can easily wipe out the bank’s entire net equity.

There is now a flight to “cash,” to a safe haven – something even better than cash: U.S. Treasury securities. Despite the talk of Republicans refusing to raise the debt ceiling, the Treasury can always print the money to pay its bondholders.

It looks like the Treasury will become the new depository of choice for those who have the financial resources. Bank deposits will fall. And with them, bank holdings of reserves at the Fed.

So far, the stock market has resisted following the plunge in bond prices. My guess is that we will now see the Great Unwinding of the great Fictitious Capital boom of 2008-2015.

So the chickens are coming hope to roost – with the “chickens” being, perhaps, the elephantine overhang of derivatives.

The spectacular collapse of Silicon Valley Bank was caused by corruption, financial recklessness, and poor decision-making. With its bailout echoing 2008’s eager bailouts for the rich, it begs the question: How much longer will Americans put up with this?

Every now and then, a development perfectly embodies everything that’s wrong with an era. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is one such development, the culmination of many years of financial recklessness, corporate entitlement, and corrupted political decision-making.

The sixteenth-largest US bank by assets up until a few days ago, SVB’s implosion is the second-worst bank failure in US history and the worst since the dominos of the global financial crisis began falling in 2008. Founded in 1983, the bank was the go-to financial institution for the glut of Silicon Valley start-ups that have spread like a rash in the era of cheap money, which was one of the factors in its downfall.

When times were good for venture capital, they were also good for SVB, which served nearly half of all US venture-backed companies. Times were particularly good this past decade or so, as the Federal Reserve ushered in an era of rock-bottom interest rates after the Great Recession. Sluggish growth and high unemployment were top of mind for the political and economic elite; low interest rates, the thinking went, would mean a lower cost of borrowing, leading to more investment and more job creation.

Things curdled in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, when inflation overtook unemployment as the political and economic concern of the day. The Federal Reserve started rapidly hiking interest rates, by a massive 450 basis points over just the last year. This time, the thinking was that by constraining investment and raising expenses for both businesses and ordinary people, the Fed would put a lid on wage growth and consumer spending and rein in inflation (even though Fed chair Jerome Powell admitted this strategy wouldn’t affect food and fuel prices, two of the areas where average Americans are most feeling the effects of inflation).

This also had the secondary effect of turning off the tap on the ceaseless flow of venture capital that was keeping start-ups, even money-losing ones, above water, helping trigger a major downturn in tech, among other things. Lean times for the sector had a knock-on effect for SVB, which suddenly faced a crunch from its venture capital–backed depositors.

But the more perilous byproduct of the Fed’s rate hikes for SVB was the fact that it had heavily invested in government bonds — whose prices tend to drop when interest rates go up and vice versa — partly because it didn’t have much else to do with the money its customers were parking with it. According to Adam Tooze, SVB was taking a hit of at least $1 billion for every twenty-five basis points that the Fed raised rates, while not investing whatsoever in interest rate hedges, leaving it particularly exposed to Powell’s inflation-fighting gambit.

What finally doomed SVB was that the resulting losses prompted a panic among depositors. This was in no small part thanks to far-right billionaire Peter Thiel’s VC firm Founders Fund, which, after finding out its investors were having trouble transferring money to its SVB accounts, ordered them to send them to other banks and had withdrawn all of its cash by the time the bank started melting down late last week. Around the same time, a newsletter popular in the VC world warned about SVB’s financial issues, while one depositor described the fear among a group chat of more than two hundred tech executives, who soon rushed to pull their money out. Behavior like this led to a classic bank run, where everyone with funds in the bank scrambles to withdraw their money at the same time, collapsing it.

All of this was enabled by the usual combination of corporate power and corruption in Washington, DC. It was Donald Trump and a GOP Congress’s 2018 rollback of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law that, at the personal request of SVB’s president three years earlier, opened the door to this kind of meltdown, by exempting banks the size of SVB from liquidity mandates and more frequent stress tests from regulators. Not that it was the SVB simply asking nicely: the bank also spent more than half a million dollars on lobbying in those three years, employing as lobbyists former staffers for then House majority leader (and now speaker) Kevin McCarthy, who enthusiastically supported the rollback.

Of course, it wasn’t just Republicans to blame. Seventeen Democrats backed the legislation, and critical to shaking off progressive criticisms of the bill was Rep. Barney Frank — the “Frank” in Dodd-Frank — who insisted it wouldn’t make a future financial crisis more likely and whose advice was cited by Wall Street–captured Democrats on the Senate floor and elsewhere as they prepared to gut the hard-fought financial regulations.

Worse than the way Frank’s advice has aged is the fact that at the time, he happened to sit on the board of Signature Bank. That institution didn’t just benefit from Frank giving a thumbs up to Congress weakening his own signature legislative achievement, but has just now been closed down by regulators after becoming the third-largest bank failure in US history at the hands of its own bank run, to prevent a wider contagion of the financial system — the exact thing Frank insisted wouldn’t happen.

Meanwhile, the individualist supermen of Silicon Valley and Wall Street have transformed overnight into willing wards of the state, demanding the government come to the rescue of wealthy investors who stand to lose. (The federal government only insures deposits up to $250,000, which means more than 85 percent of SVB’s deposits were uninsured.) Larry Summers, fresh off railing against “unreasonably generous student loan relief,” is now telling us it’s “not the time for moral hazard lectures or for lesson administering or for alarm about the political consequences of ‘bailouts,’” as he demanded that all uninsured deposits “be fully backed by Monday morning.”

Unsurprisingly, Summers and his ilk won out. Despite pledging not to bail out SVB and Signature, the Treasury, Fed, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation invoked a “systemic risk exception” to announce that all depositors, even those above the $250,000 threshold, will “have access to all of their money” starting today, and that it would start an emergency lending program for banks to ensure as much.

Some are drawing a distinction here from the infamous and hated 2008 bailouts, because this time, the banks aren’t being rescued and taxpayers aren’t footing the bill (the funds being used to cover depositors are made up of fees that were levied on banks). But at the end of the day, the government is stepping in to ensure wealthy investors and executives don’t lose a cent from this debacle, despite the fact that they knew full well their deposits weren’t insured. Even the Wall Street Journal calls this a “de facto bailout.”

There is the obvious, wealth-inflected unfairness inherent to all this. Once again, the big guys are quickly doused with a firehose of money when they get into trouble after failing to carry out basic due diligence. Meanwhile, working people are lectured about personal responsibility, and are forced to scratch and claw to be freed of crushing debt, for basic economic protections in the middle of an economic catastrophe, and to get one-time stimulus checks that barely cover a month’s rent in many cities.

There’s also the question of what kind of future irresponsibility this will encourage. After all, investors just saw (again) firsthand that the federal government will step in to rescue them even if their deposits are uninsured — no matter how irresponsible the financial institution they were parking their money in happened to be, as long as there’s a whiff of potential wider financial instability around the corner. We might also ask what other economic mayhem might be triggered by the Fed’s determination to fight inflation through cranking up interest rates; SVB is just one of many possible entities that could spiral into instability as the central bank barrels ahead with a plan that experts warn will trigger recession, as the cryptocurrency collapse already showed us.

Behind it all, there’s a question: How much longer people will tolerate a system like this? One where vast amounts of wealth are misdirected to unproductive ends in the middle of world historical crises, then frittered away in speculative recklessness that nearly brings the entire structure down, only for those with the money to parachute to safety while everyone else remains condemned to austerity. The original bank bailouts set off a cascade of popular anger that’s irrevocably shaped the landscape of twenty-first-century politics, from Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders campaigns to the Tea Party movement and the Trump presidency. What will it look like if they keep on happening?