July 15, 2024

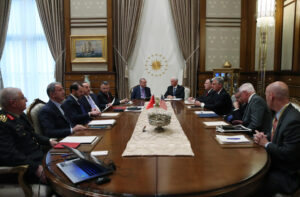

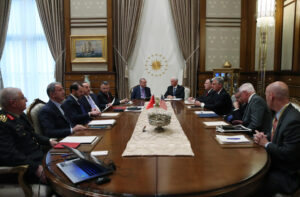

US Vice President Mike Pence and US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited Turkey on October 17, 2019, to meet with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

LONG READ

Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

Two inside sources from the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) have cast doubt on the Turkish government’s narrative regarding a coup attempt in 2016, which many believe was a false flag operation designed to consolidate the power of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

In his book titled “Never Give an Inch,” released last year, Mike Pompeo, who served as CIA director and secretary of state in the Trump administration, described the events of July 15, 2016 as a “purported ‘coup,'” casting doubt on the accuracy of the Erdoğan government’s narrative.

“Turkey has every incentive to align firmly with the West as well as a population that welcome it and benefit from it. Yet ever since a purported ‘coup’ in 2016, President Erdoğan had gone full Islamist-authoritarian. I spent countless hours with him and his national security advisor, Ibrahim Kalin, and intel chief, Hakan Fidan,” Pompeo wrote in his book.

When he visited Turkey for the first time as CIA director in 2017, he said he was subjected to a lengthy video of the coup events, apparently prepared by the Erdoğan government as a propaganda piece to convince foreign visitors of its narrative regarding the events of July 15.

He made another visit to Turkey in 2018 as secretary of state and then again in 2019, accompanying Vice President Mike Pence to persuade President Erdoğan to halt military intervention in Syria. During the visit Erdoğan asked for a few minutes alone with Pence, but the meeting lasted much longer than expected.

He described the trip as challenging and provided details in his book: “When we arrived at Erdoğan’s palace, he asked for a one-on-one meeting with the vice president for “a few minutes”. After about half an hour, I told our hosts that I needed to see the vice president, No dice. About twenty minutes went by, and now I was determined. Without permission, I walked down the hall and tried to push open the door of the room that Erdoğan and vice president were meeting in. It was locked. I then told my counterpart that we were going to break through the door- I was worried that Vice President Pence was being subjected to the same three-hour video of the 2016 coup that I had been forced to watch on my first visit to Turkey as CIA Director in 2017. The video was so long and obnoxious that I considered it a mental health issue!”

Conflicting expert reports, inconsistency in the timeline of events, ambiguous flight information data, missing crucial recordings, hastily conducted trial proceedings, suppression of evidence sought by the defense and an obvious mismatch between damage to the impact site and the type of bombs allegedly used all pointed in the direction of a false flag plot orchestrated by the Turkish government.

As a result of the false flag operation, Erdoğan further consolidated his power, transitioning the Turkish parliamentary democracy into an imperial-style presidential rule with no checks and balances. He exerted significant control over the legislative and judicial branches, appointing Islamists and nationalist/neonationalist allies to key government positions.

In the words of the CIA operations officer, who evidently has a deep understanding of Turkey, Erdoğan benefited personally from the coup events but inflicted serious harm on Turkey as a whole.

“The impact of the alleged coup attempt devastated Turkey’s chances of meaningful collaboration with the European Union and solidified all negative impressions or assumptions about Erdogan and his regime. Erdogan may have benefited in the short term but hurt Turkiye in the long term. Turkish people are less free and more afraid, their future looks more uncertain, and the firing of judges only weakens the judicial system and the world’s confidence in the Turkish government to afford its people any fair trials.”

Abdullah Bozkurt/Stockholm

Two inside sources from the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) have cast doubt on the Turkish government’s narrative regarding a coup attempt in 2016, which many believe was a false flag operation designed to consolidate the power of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

In his book titled “Never Give an Inch,” released last year, Mike Pompeo, who served as CIA director and secretary of state in the Trump administration, described the events of July 15, 2016 as a “purported ‘coup,'” casting doubt on the accuracy of the Erdoğan government’s narrative.

“Turkey has every incentive to align firmly with the West as well as a population that welcome it and benefit from it. Yet ever since a purported ‘coup’ in 2016, President Erdoğan had gone full Islamist-authoritarian. I spent countless hours with him and his national security advisor, Ibrahim Kalin, and intel chief, Hakan Fidan,” Pompeo wrote in his book.

When he visited Turkey for the first time as CIA director in 2017, he said he was subjected to a lengthy video of the coup events, apparently prepared by the Erdoğan government as a propaganda piece to convince foreign visitors of its narrative regarding the events of July 15.

He made another visit to Turkey in 2018 as secretary of state and then again in 2019, accompanying Vice President Mike Pence to persuade President Erdoğan to halt military intervention in Syria. During the visit Erdoğan asked for a few minutes alone with Pence, but the meeting lasted much longer than expected.

He described the trip as challenging and provided details in his book: “When we arrived at Erdoğan’s palace, he asked for a one-on-one meeting with the vice president for “a few minutes”. After about half an hour, I told our hosts that I needed to see the vice president, No dice. About twenty minutes went by, and now I was determined. Without permission, I walked down the hall and tried to push open the door of the room that Erdoğan and vice president were meeting in. It was locked. I then told my counterpart that we were going to break through the door- I was worried that Vice President Pence was being subjected to the same three-hour video of the 2016 coup that I had been forced to watch on my first visit to Turkey as CIA Director in 2017. The video was so long and obnoxious that I considered it a mental health issue!”

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited Turkey on October 17, 2018 to meet with Turkish President Erdoğan as well as his then-intelligence chief Hakan Fidan and national security advisor Ibrahim Kalin.

Another challenge to the Turkish government’s narrative came from a CIA operations officer who was in Turkey during the events of July 15. The interview, conducted anonymously, was published in April 2024 on the Homeland Security Today website, a nonprofit association operating under the Government Technology & Services Coalition. The interview was conducted by Mahmut Cengiz, an associate professor and research faculty with the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center (TraCCC) and the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.

“The Turkish military is well-trained, well-experienced in coups, and has advanced weapons. It would not have closed just one way of the Bosphorus Bridge and done a coup,” said the CIA officer, referring to the closure of one side of the bridge on the night of July 15. Court testimony from troops during coup trials revealed that soldiers were ordered to close one side of the bridge in response to a reported terrorist attack.

In April 2021 Nordic Monitor published classified intelligence reports filed by Turkish intelligence agency MIT and shared with the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) in the weeks and days preceding the coup attempt. The reports frequently highlighted the risks of imminent terrorist attacks on civilian and military targets in Istanbul and Ankara in late June and early July 2016. This context explains why many soldiers accused of involvement in the failed coup on July 15 believed they were responding to terror threats rather than participating in a coup attempt.

The intelligence messages published before July 15 vividly depict the operational environment of the Turkish military. These alerts, sent to every military unit across the country, indicated a heightened awareness that a terrorist attack could occur at any moment. The anxiety over potential attacks was compounded by a series of deadly terror incidents in the heart of the Turkish capital in 2015 and early 2016, including one at military housing units in Ankara, which deeply unsettled the security establishment.

“Initial assessment that it may have been a terrorist attack or a response to a terrorist attack, which may have included members of the Turkish military. During that time, there were multiple terrorist attacks throughout the country, carried out by ISIS [Islamic State in Iraq and Syria] and others by PKK [Kurdistan Workers’ Party],” said the CIA officer, who was stationed in Turkey at the time.

Another challenge to the Turkish government’s narrative came from a CIA operations officer who was in Turkey during the events of July 15. The interview, conducted anonymously, was published in April 2024 on the Homeland Security Today website, a nonprofit association operating under the Government Technology & Services Coalition. The interview was conducted by Mahmut Cengiz, an associate professor and research faculty with the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center (TraCCC) and the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University.

“The Turkish military is well-trained, well-experienced in coups, and has advanced weapons. It would not have closed just one way of the Bosphorus Bridge and done a coup,” said the CIA officer, referring to the closure of one side of the bridge on the night of July 15. Court testimony from troops during coup trials revealed that soldiers were ordered to close one side of the bridge in response to a reported terrorist attack.

In April 2021 Nordic Monitor published classified intelligence reports filed by Turkish intelligence agency MIT and shared with the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) in the weeks and days preceding the coup attempt. The reports frequently highlighted the risks of imminent terrorist attacks on civilian and military targets in Istanbul and Ankara in late June and early July 2016. This context explains why many soldiers accused of involvement in the failed coup on July 15 believed they were responding to terror threats rather than participating in a coup attempt.

The intelligence messages published before July 15 vividly depict the operational environment of the Turkish military. These alerts, sent to every military unit across the country, indicated a heightened awareness that a terrorist attack could occur at any moment. The anxiety over potential attacks was compounded by a series of deadly terror incidents in the heart of the Turkish capital in 2015 and early 2016, including one at military housing units in Ankara, which deeply unsettled the security establishment.

“Initial assessment that it may have been a terrorist attack or a response to a terrorist attack, which may have included members of the Turkish military. During that time, there were multiple terrorist attacks throughout the country, carried out by ISIS [Islamic State in Iraq and Syria] and others by PKK [Kurdistan Workers’ Party],” said the CIA officer, who was stationed in Turkey at the time.

US Vice President Mike Pence visited Turkey on October 17, 2019 to convince President Erdoğan to halt military operations in Syria.

The CIA officer also found it perplexing to witness the Turkish government’s swift removal of over 10,000 alleged members of the Gülen movement from various government institutions within just 12 hours of the alleged coup. ” … they [Turkish officials] must explain how they could produce a long list of suspects” in such a short period of time, he said.

Although the Turkish military itself said the military mobilization on July 15 was very limited and involved less than 1 percent of the troops, the Erdoğan government was quick to conduct mass purges of senior officers from NATO’s second largest army in terms of manpower. A total of 23,971 personnel, primarily in the officer ranks, were purged from the Turkish army without any military, administrative or criminal investigations.

The purge primarily targeted pro-NATO officers or individuals who had served in NATO assignments, at NATO headquarters in Brussels or at NATO-affiliated bases in the US, Norway, Germany, Italy and Spain. Evidence presented in coup trials revealed that the profiling of those to be purged was quietly carried out between 2014 and 2016 by Turkish intelligence agency MIT and its extensive network of informants.

The purge took a real toll on staff officers who were the backbone in the operational and planning capabilities of the army. Out of 1,886 staff officers, 1,524 were purged, which amounted to 81 percent of all staff officers. Overall, 10,468 officers or one-third of the entire officer ranks were removed from the Turkish military. What is more, two-thirds of all generals and admirals were summarily and abruptly purged or forced to retire.

Many senior officers were either on vacation or had nothing to do with the mobilization on July 15, yet they were arrested and imprisoned because their military background indicated they had served at NATO bases in the US, Italy, Spain, Germany or Norway in the past.

The CIA officer also found it perplexing to witness the Turkish government’s swift removal of over 10,000 alleged members of the Gülen movement from various government institutions within just 12 hours of the alleged coup. ” … they [Turkish officials] must explain how they could produce a long list of suspects” in such a short period of time, he said.

Although the Turkish military itself said the military mobilization on July 15 was very limited and involved less than 1 percent of the troops, the Erdoğan government was quick to conduct mass purges of senior officers from NATO’s second largest army in terms of manpower. A total of 23,971 personnel, primarily in the officer ranks, were purged from the Turkish army without any military, administrative or criminal investigations.

The purge primarily targeted pro-NATO officers or individuals who had served in NATO assignments, at NATO headquarters in Brussels or at NATO-affiliated bases in the US, Norway, Germany, Italy and Spain. Evidence presented in coup trials revealed that the profiling of those to be purged was quietly carried out between 2014 and 2016 by Turkish intelligence agency MIT and its extensive network of informants.

The purge took a real toll on staff officers who were the backbone in the operational and planning capabilities of the army. Out of 1,886 staff officers, 1,524 were purged, which amounted to 81 percent of all staff officers. Overall, 10,468 officers or one-third of the entire officer ranks were removed from the Turkish military. What is more, two-thirds of all generals and admirals were summarily and abruptly purged or forced to retire.

Many senior officers were either on vacation or had nothing to do with the mobilization on July 15, yet they were arrested and imprisoned because their military background indicated they had served at NATO bases in the US, Italy, Spain, Germany or Norway in the past.

Pro-Erdoğan supporters rally at the Bosporus Bridge in Istanbul on July 21, 2016. (Photo by YASIN AKGUL / AFP)

The purge following the alleged coup was not confined to the military but extended to the judiciary, police, intelligence agencies, academic institutions and others. More than 4,000 judges and prosecutors, including senior figures from the top appeals and constitutional courts, were immediately dismissed. This underscored the Erdoğan government’s intent to influence the narrative in coup trials, transform the Turkish judiciary into a political tool under Erdoğan’s control and suppress opposition and dissent.

Nearly 200 media outlets were shuttered, hundreds of journalists were arrested or forced into exile, thousands of NGOs were closed, and the wealth and assets of many businesses, totaling tens of billions of dollars, were seized and redistributed to Erdoğan’s associates and supporters.

According to a statement by Justice Minister Yılmaz Tunç to the state-run Anadolu news agency on July 12, 2024, a total of 705,172 people have faced legal action, primarily through detention and arrest, since July 2016. Among them, 125,456 were convicted on bogus charges related to terrorism and/or the coup attempt.

The CIA officer noted that the Erdoğan government’s attribution of the coup to the Gülen movement served multiple purposes, including discrediting Fethullah Gülen, who has distanced himself from the Erdoğan government and opposed its use of Islam for political objectives.

Regarding the failure of the Erdoğan government to secure the extradition of Gülen, who has been in self-exile in the US since 1999, the CIA officer said, “From a legal standpoint, the Turkish government did not present the United States with any shred of legal evidence that proves Gulen was involved in the alleged coup attempt. Most of the documents presented would not stand a chance in any court of law. The documents were filled with emotional tirades and assumptions, which would not have been enough to indict Gulen, let alone extradited to Turkiye.”

The purge following the alleged coup was not confined to the military but extended to the judiciary, police, intelligence agencies, academic institutions and others. More than 4,000 judges and prosecutors, including senior figures from the top appeals and constitutional courts, were immediately dismissed. This underscored the Erdoğan government’s intent to influence the narrative in coup trials, transform the Turkish judiciary into a political tool under Erdoğan’s control and suppress opposition and dissent.

Nearly 200 media outlets were shuttered, hundreds of journalists were arrested or forced into exile, thousands of NGOs were closed, and the wealth and assets of many businesses, totaling tens of billions of dollars, were seized and redistributed to Erdoğan’s associates and supporters.

According to a statement by Justice Minister Yılmaz Tunç to the state-run Anadolu news agency on July 12, 2024, a total of 705,172 people have faced legal action, primarily through detention and arrest, since July 2016. Among them, 125,456 were convicted on bogus charges related to terrorism and/or the coup attempt.

The CIA officer noted that the Erdoğan government’s attribution of the coup to the Gülen movement served multiple purposes, including discrediting Fethullah Gülen, who has distanced himself from the Erdoğan government and opposed its use of Islam for political objectives.

Regarding the failure of the Erdoğan government to secure the extradition of Gülen, who has been in self-exile in the US since 1999, the CIA officer said, “From a legal standpoint, the Turkish government did not present the United States with any shred of legal evidence that proves Gulen was involved in the alleged coup attempt. Most of the documents presented would not stand a chance in any court of law. The documents were filled with emotional tirades and assumptions, which would not have been enough to indict Gulen, let alone extradited to Turkiye.”

Fethullah Gülen is seen visiting a hospital in Philadelphia for a checkup.

The officer confirmed the stance taken by the US Department of Justice regarding the extradition of Gülen. Despite repeated extradition requests and efforts by the Erdoğan government to secure Gülen’s temporary detention in the US, American officials resisted these demands. The Justice Department concluded that the Turkish requests did not meet the legal standards for extradition set by the US-Turkey extradition treaty and US law. Therefore, extradition could not proceed without additional evidence substantiating the allegations against Gülen.

Similar skepticism was also expressed by Turkey’s other NATO allies. The German Federal Intelligence Service (BND) was unconvinced that Gülen was behind the failed coup in Turkey. “Turkey has tried to convince us of that at every level but so far it has not succeeded,” Bruno Kahl, the head of the BND, said in an interview with Der Spiegel published in March 2017.

In April 2017 German intelligence expert and author Erich Schmidt-Eenboom asserted that Erdoğan, not the Gülen movement, was behind the failed coup in Turkey, citing intelligence reports from the CIA and BND. Speaking during a program on German public broadcaster ZDF, Schmidt-Eenboom said: “According to CIA analyses, the so-called coup attempt was staged by Erdogan to prevent a real coup. The BND, CIA, and other Western intelligence services do not see the slightest evidence implicating Gülen in instigating the coup attempt.”

The role of Turkish intelligence in coordinating what turned out to be a false flag coup attempt was indeed exposed during the coup trials, despite efforts by judges to suppress evidence, reject nearly all motions filed by the defense and refuse to summon intelligence and military chiefs for cross-examination. Multiple pieces of evidence surfaced pointing to the spy agency, revealing its involvement in the events.

In a highly unusual occurrence, MIT agents paid a visit and toured Akıncı Air Base, months before the July 15 events. The base was later alleged by the government to be the putschists’ headquarters.

Maj. Adnan Arıkan testified in court on January 14, 2019 that a team of MIT agents had visited Akıncı Air Base in May 2016, two months before the coup attempt, describing the visit as unprecedented and aimed at scouting the base for the purposes of the false flag.

The officer confirmed the stance taken by the US Department of Justice regarding the extradition of Gülen. Despite repeated extradition requests and efforts by the Erdoğan government to secure Gülen’s temporary detention in the US, American officials resisted these demands. The Justice Department concluded that the Turkish requests did not meet the legal standards for extradition set by the US-Turkey extradition treaty and US law. Therefore, extradition could not proceed without additional evidence substantiating the allegations against Gülen.

Similar skepticism was also expressed by Turkey’s other NATO allies. The German Federal Intelligence Service (BND) was unconvinced that Gülen was behind the failed coup in Turkey. “Turkey has tried to convince us of that at every level but so far it has not succeeded,” Bruno Kahl, the head of the BND, said in an interview with Der Spiegel published in March 2017.

In April 2017 German intelligence expert and author Erich Schmidt-Eenboom asserted that Erdoğan, not the Gülen movement, was behind the failed coup in Turkey, citing intelligence reports from the CIA and BND. Speaking during a program on German public broadcaster ZDF, Schmidt-Eenboom said: “According to CIA analyses, the so-called coup attempt was staged by Erdogan to prevent a real coup. The BND, CIA, and other Western intelligence services do not see the slightest evidence implicating Gülen in instigating the coup attempt.”

The role of Turkish intelligence in coordinating what turned out to be a false flag coup attempt was indeed exposed during the coup trials, despite efforts by judges to suppress evidence, reject nearly all motions filed by the defense and refuse to summon intelligence and military chiefs for cross-examination. Multiple pieces of evidence surfaced pointing to the spy agency, revealing its involvement in the events.

In a highly unusual occurrence, MIT agents paid a visit and toured Akıncı Air Base, months before the July 15 events. The base was later alleged by the government to be the putschists’ headquarters.

Maj. Adnan Arıkan testified in court on January 14, 2019 that a team of MIT agents had visited Akıncı Air Base in May 2016, two months before the coup attempt, describing the visit as unprecedented and aimed at scouting the base for the purposes of the false flag.

Turkish F-16 fighter jets

The base command initially denied MIT’s request to visit the base, explaining that it was busy with some 100 F-16 combat pilots who were in training at the time. The MIT agents could have paid a visit to other air bases that were less busy in Ankara or other cities, but MIT’S insistence on visiting Akıncı was found quite strange, Arıkan said.

In the end Air Force Commander Gen. Abidin Ünal, a close confidant of President Erdoğan, with whom he met secretly outside the chain of command several times, allowed the visit, overruling the base command, and MIT sent a team of 70 agents to look around and scout the base. “What benefit did such a large delegation get from this trip? What were the duties of the people in this delegation and what were their activities on July 15, 2016?“ Arıkan asked.

“The MIT delegation toured almost every place on the base including the flight tower and locations where the 141st, 142nd and 143rd squadrons were deployed as well as hangars and ammunition depots. From a military point of view, this was really a reconnaissance. Those who understand a little bit about intelligence, those who know a little bit about the principles of unconventional warfare, understand the purpose of this activity very well,” Arıkan said.

During the coup trials, it was revealed that MIT had been secretly working with a lieutenant colonel in the air force to direct warplanes to buzz the capital city of Ankara in order to bolster the perception that a false flag was a real coup attempt by the Turkish Armed Forces.

Several senior military commanders testified during the trial that MIT agent Korkut Gül coordinated the activity in the tower at Akıncı Air Base manned by Lt. Col. Nihat Altıntop, the airfield operations commander. Altıntop was in the tower and was frequently on the phone with the MIT agent.

It was also revealed that Intelligence chief Hakan Fidan had lengthy talks with then-chief of general staff Hulusi Akar in the days leading up to the coup attempt, with their final meeting on July 14 lasting for hours. These encounters were described as highly unusual by Akar’s aides, who were instructed not to record his entry to military bases. Court evidence further revealed that the coup plan was executed by two senior intelligence officers, Sadık Üstün and Kemal Eskintan, both with military backgrounds who had been recruited by MIT long before the events unfolded.

The base command initially denied MIT’s request to visit the base, explaining that it was busy with some 100 F-16 combat pilots who were in training at the time. The MIT agents could have paid a visit to other air bases that were less busy in Ankara or other cities, but MIT’S insistence on visiting Akıncı was found quite strange, Arıkan said.

In the end Air Force Commander Gen. Abidin Ünal, a close confidant of President Erdoğan, with whom he met secretly outside the chain of command several times, allowed the visit, overruling the base command, and MIT sent a team of 70 agents to look around and scout the base. “What benefit did such a large delegation get from this trip? What were the duties of the people in this delegation and what were their activities on July 15, 2016?“ Arıkan asked.

“The MIT delegation toured almost every place on the base including the flight tower and locations where the 141st, 142nd and 143rd squadrons were deployed as well as hangars and ammunition depots. From a military point of view, this was really a reconnaissance. Those who understand a little bit about intelligence, those who know a little bit about the principles of unconventional warfare, understand the purpose of this activity very well,” Arıkan said.

During the coup trials, it was revealed that MIT had been secretly working with a lieutenant colonel in the air force to direct warplanes to buzz the capital city of Ankara in order to bolster the perception that a false flag was a real coup attempt by the Turkish Armed Forces.

Several senior military commanders testified during the trial that MIT agent Korkut Gül coordinated the activity in the tower at Akıncı Air Base manned by Lt. Col. Nihat Altıntop, the airfield operations commander. Altıntop was in the tower and was frequently on the phone with the MIT agent.

It was also revealed that Intelligence chief Hakan Fidan had lengthy talks with then-chief of general staff Hulusi Akar in the days leading up to the coup attempt, with their final meeting on July 14 lasting for hours. These encounters were described as highly unusual by Akar’s aides, who were instructed not to record his entry to military bases. Court evidence further revealed that the coup plan was executed by two senior intelligence officers, Sadık Üstün and Kemal Eskintan, both with military backgrounds who had been recruited by MIT long before the events unfolded.

Hulusi Akar (left) and Hakan Fidan

Üstün’s role in the false military bid to purportedly oust Erdoğan was exposed when he made one major mistake in timing. He prematurely identified the alleged leader of the putschists, triggering closer scrutiny of his role in the July 15 events.

During the court hearings of suspected putschists who knew him well, many came forward revealing further details of his role in the false flag operation. Immediately after the coup events, the Erdoğan government sent him off to Australia as a diplomatic attaché, out of the reach of defense attorneys who wanted to put him on the stand and cross-examine him. He never testified in court despite repeated motions filed by defense lawyers in multiple court cases and was not summoned to testify before the parliamentary commission set up to investigate the failed coup.

In a major blunder, Üstün prematurely named a decorated general, senior member of the Supreme Military Council (YAŞ) and former Air Forces Commander Akın Öztürk as the leader of the putschists when the general was still at his daughter’s home, located some four or five kilometers from Akıncı Air Base, the alleged headquarters of the putschists. Öztürk, who had no affiliation with the Gülen movement, was completely unaware of the plot unfolding around him and was playing with his grandchildren on the night of the coup attempt.

Eskintan, who oversaw armed jihadist groups in Syria on behalf of MIT, facilitated the clandestine transportation of unregistered firearms, ammunition and jihadist fighters from Syria prior to the events of July 15, 2016. The aim of this operation was to provoke a state of chaos, leading to tragic civilian and military casualties due to the ensuing violence.

In fact, bullets extracted from the bodies of civilians killed on the night of July 15 were found not to be registered in the Turkish military arsenal. Despite motions by defense lawyers representing alleged putschists, the government refused to conduct thorough autopsies, ballistic examinations or hand swabs to determine if a person had fired a gun from powder residue imprints in the palm.

Eskintan, who served as head of special operations within the agency, is known by the nom de guerre “Abu Furkan” in Syria. He has been extensively involved in collaborating with jihadist groups in both Syria and Libya, using them as proxies to advance the political objectives of the Erdoğan government.

It was also revealed that key statements extracted from suspects who endured lengthy torture sessions, threats of rape and harm to their loved ones were prepared in advance and fabricated. The foundational document used by a public prosecutor to initiate coup investigations and referenced in all coup trials was also scripted. This document listed events that had not yet occurred or did not happen at all, suggesting that the government had prepared the sequence of events well in advance to portray the limited military mobilization as a coup attempt.

Üstün’s role in the false military bid to purportedly oust Erdoğan was exposed when he made one major mistake in timing. He prematurely identified the alleged leader of the putschists, triggering closer scrutiny of his role in the July 15 events.

During the court hearings of suspected putschists who knew him well, many came forward revealing further details of his role in the false flag operation. Immediately after the coup events, the Erdoğan government sent him off to Australia as a diplomatic attaché, out of the reach of defense attorneys who wanted to put him on the stand and cross-examine him. He never testified in court despite repeated motions filed by defense lawyers in multiple court cases and was not summoned to testify before the parliamentary commission set up to investigate the failed coup.

In a major blunder, Üstün prematurely named a decorated general, senior member of the Supreme Military Council (YAŞ) and former Air Forces Commander Akın Öztürk as the leader of the putschists when the general was still at his daughter’s home, located some four or five kilometers from Akıncı Air Base, the alleged headquarters of the putschists. Öztürk, who had no affiliation with the Gülen movement, was completely unaware of the plot unfolding around him and was playing with his grandchildren on the night of the coup attempt.

Eskintan, who oversaw armed jihadist groups in Syria on behalf of MIT, facilitated the clandestine transportation of unregistered firearms, ammunition and jihadist fighters from Syria prior to the events of July 15, 2016. The aim of this operation was to provoke a state of chaos, leading to tragic civilian and military casualties due to the ensuing violence.

In fact, bullets extracted from the bodies of civilians killed on the night of July 15 were found not to be registered in the Turkish military arsenal. Despite motions by defense lawyers representing alleged putschists, the government refused to conduct thorough autopsies, ballistic examinations or hand swabs to determine if a person had fired a gun from powder residue imprints in the palm.

Eskintan, who served as head of special operations within the agency, is known by the nom de guerre “Abu Furkan” in Syria. He has been extensively involved in collaborating with jihadist groups in both Syria and Libya, using them as proxies to advance the political objectives of the Erdoğan government.

It was also revealed that key statements extracted from suspects who endured lengthy torture sessions, threats of rape and harm to their loved ones were prepared in advance and fabricated. The foundational document used by a public prosecutor to initiate coup investigations and referenced in all coup trials was also scripted. This document listed events that had not yet occurred or did not happen at all, suggesting that the government had prepared the sequence of events well in advance to portray the limited military mobilization as a coup attempt.

Kemal Eskintan, Turkish intelligence agent who coordinated jihadist groups in Syria and Libya.

No evidence has surfaced showing that a commission named the Council of Peace in the Homeland (Yurtta Sulh Konseyi), which purportedly plotted the coup, was actually formed. Additionally, the members of this supposed council have never been identified.

There was no military plan to execute a coup on July 15, unlike past successful coups where detailed planning with numerous contingencies was typical. Prosecutors singled out F-16 fighter jets allegedly used to bomb parliament and other locations, but it was later revealed that these planes had not flown on July 15. Despite requests from the defense during coup trials, the government refused to share the jets’ flight data or the recorded video footage from the airbase.

There was only one directive transmitted through MEDAS, the Turkish military’s secure communications channel, that involved reassignments as part of the coup attempt. The message was approved by a brigadier general, which was unusual because such directives typically involved officers at higher ranks, such as full generals or admirals.

In other words the directive written by the lower-ranking officer, assigning duties to higher-ranking officers, violated the chain of command. It was later discovered that some of the ranks listed on the assignment sheet were recorded incorrectly, indicating that the document was prepared outside of General Staff headquarters and based on outdated data.

Many commanders in the field found the message suspicious, being outside the chain of command, and did not participate in the coup or the military mobilization, which was limited to only 1 percent of the Turkish military. The operation, designed to fail from the start according to experts, was contained easily and quickly.

No evidence has surfaced showing that a commission named the Council of Peace in the Homeland (Yurtta Sulh Konseyi), which purportedly plotted the coup, was actually formed. Additionally, the members of this supposed council have never been identified.

There was no military plan to execute a coup on July 15, unlike past successful coups where detailed planning with numerous contingencies was typical. Prosecutors singled out F-16 fighter jets allegedly used to bomb parliament and other locations, but it was later revealed that these planes had not flown on July 15. Despite requests from the defense during coup trials, the government refused to share the jets’ flight data or the recorded video footage from the airbase.

There was only one directive transmitted through MEDAS, the Turkish military’s secure communications channel, that involved reassignments as part of the coup attempt. The message was approved by a brigadier general, which was unusual because such directives typically involved officers at higher ranks, such as full generals or admirals.

In other words the directive written by the lower-ranking officer, assigning duties to higher-ranking officers, violated the chain of command. It was later discovered that some of the ranks listed on the assignment sheet were recorded incorrectly, indicating that the document was prepared outside of General Staff headquarters and based on outdated data.

Many commanders in the field found the message suspicious, being outside the chain of command, and did not participate in the coup or the military mobilization, which was limited to only 1 percent of the Turkish military. The operation, designed to fail from the start according to experts, was contained easily and quickly.

Sadık Üstün, an agent of Turkey’s intelligence agency MIT, who runs secret ops in Libya. He is seen here giving a speech in Brussels in 2013.

A case involving the bombing of the Turkish parliament, allegedly by coup plotters according to the government narrative, collapsed in court when the defendants took the stand and refuted the prosecutor’s allegations.

The bombing of the nation’s parliament building, an unprecedented move that made no sense and lacked a motive, appears to have been staged by elements of intelligence as part of a plot to sideline legislative and judicial oversight and transform Turkey into an authoritarian regime run by one man and his inner circle.

Some likened parliament’s bombing to the Reichstag fire, an arson attack on the German parliament in 1933 that helped the Nazis consolidate their grip on the government and paved the way for the rise of Adolf Hitler.

A case involving the bombing of the Turkish parliament, allegedly by coup plotters according to the government narrative, collapsed in court when the defendants took the stand and refuted the prosecutor’s allegations.

The bombing of the nation’s parliament building, an unprecedented move that made no sense and lacked a motive, appears to have been staged by elements of intelligence as part of a plot to sideline legislative and judicial oversight and transform Turkey into an authoritarian regime run by one man and his inner circle.

Some likened parliament’s bombing to the Reichstag fire, an arson attack on the German parliament in 1933 that helped the Nazis consolidate their grip on the government and paved the way for the rise of Adolf Hitler.

Conflicting expert reports, inconsistency in the timeline of events, ambiguous flight information data, missing crucial recordings, hastily conducted trial proceedings, suppression of evidence sought by the defense and an obvious mismatch between damage to the impact site and the type of bombs allegedly used all pointed in the direction of a false flag plot orchestrated by the Turkish government.

As a result of the false flag operation, Erdoğan further consolidated his power, transitioning the Turkish parliamentary democracy into an imperial-style presidential rule with no checks and balances. He exerted significant control over the legislative and judicial branches, appointing Islamists and nationalist/neonationalist allies to key government positions.

In the words of the CIA operations officer, who evidently has a deep understanding of Turkey, Erdoğan benefited personally from the coup events but inflicted serious harm on Turkey as a whole.

“The impact of the alleged coup attempt devastated Turkey’s chances of meaningful collaboration with the European Union and solidified all negative impressions or assumptions about Erdogan and his regime. Erdogan may have benefited in the short term but hurt Turkiye in the long term. Turkish people are less free and more afraid, their future looks more uncertain, and the firing of judges only weakens the judicial system and the world’s confidence in the Turkish government to afford its people any fair trials.”

.gif)