The concept of 'National Bolshevism': An interpretative essay

Erik Van Ree

Journal of Political Ideologies

Volume 6, 2001 - Issue 3

Pages 289-307 | Published online: 04 Aug 2010

The concept of 'National Bolshevism' is mainly used in studies of twentieth-century German and Russian political radicalism. It has been subject to considerable inflation. The present article presents a case for a restrictive definition. National Bolshevism can most properly be defined as that radical tendency which combines a commitment to class struggle and total nationalization of the means of production with extreme state chauvinism. Definitional strictness is not only justified by the historical sources of the term in Germany and Russia. A further advantage of a narrow definition is that it helps us get important distinctions among nationalist and communist movements and states into focus. It is also helpful in bringing out a remarkable asymmetry between the propensity of nationalists and communists to adopt each other's programme.

It’s possible that I shall make an ass of myself. But in that case one can always get out of it with a little dialectic. I have, of course, so worded my proposition as to be right either way (K.Marx, Letter to F.Engels on the Indian Mutiny)

Wednesday, January 22, 2020

Communist Upbringing under Stalin: The Political Socialization and Militarization of Soviet

Youth, 1934-1941

Seth Bernstein

Doctor of Philosophy

Department of History

University of Toronto

2013

Abstract:

In 1935 the Communist Youth League (Komsomol) embraced a policy called

“communist upbringing” that changed the purpose of Soviet official youth culture. Founded in 1918, the Komsomol had been an organization of cultural proletarianization and economic

mobilization. After the turmoil of Stalin’s revolution from above, Soviet leaders declared that thecountry had entered the period of socialism. Under the new conditions of socialism, including the threat of war with the capitalist world, “communist upbringing” transformed the youth league into an organization of mass socialization meant to mold youth in the shape of the regime.

The key goals of “communist upbringing” were to broaden the influence of Soviet

political culture and to enforce a code of “cultured” behavior among youth. Youth leaders

transformed the Komsomol from a league of young male workers into an organization that

included more than a quarter of Soviet youth by 1941, incorporating more adolescents, women, and non-workers. Employing recreation, reward and disciplinary practices that blurred into repression, mass socialization in the Komsomol attempted to create a cohort of “Soviet” youth—sober, orderly, physically strong and politically loyal to Stalin’s regime.

The transformation of youth culture under Stalin reflected a general shift in Stalinist

social policies in the mid-1930s. Historians have argued whether this turn was a conservative

iii retreat from Bolshevik ideals or the use of apolitical modern state practices in the service of

socialism. This dissertation shows that while youth leaders were intensely interested in modern state practices, they made these practices into central elements of Soviet socialism. Through the Komsomol, youth became a resource for the state to guide along the uncertain and dangerous road to the future of communism. Reacting to domestic and international crises, Stalinist leaders created a system of state socialization for youth that would last until the fall of the Soviet Union.

Youth, 1934-1941

Seth Bernstein

Doctor of Philosophy

Department of History

University of Toronto

2013

Abstract:

In 1935 the Communist Youth League (Komsomol) embraced a policy called

“communist upbringing” that changed the purpose of Soviet official youth culture. Founded in 1918, the Komsomol had been an organization of cultural proletarianization and economic

mobilization. After the turmoil of Stalin’s revolution from above, Soviet leaders declared that thecountry had entered the period of socialism. Under the new conditions of socialism, including the threat of war with the capitalist world, “communist upbringing” transformed the youth league into an organization of mass socialization meant to mold youth in the shape of the regime.

The key goals of “communist upbringing” were to broaden the influence of Soviet

political culture and to enforce a code of “cultured” behavior among youth. Youth leaders

transformed the Komsomol from a league of young male workers into an organization that

included more than a quarter of Soviet youth by 1941, incorporating more adolescents, women, and non-workers. Employing recreation, reward and disciplinary practices that blurred into repression, mass socialization in the Komsomol attempted to create a cohort of “Soviet” youth—sober, orderly, physically strong and politically loyal to Stalin’s regime.

The transformation of youth culture under Stalin reflected a general shift in Stalinist

social policies in the mid-1930s. Historians have argued whether this turn was a conservative

iii retreat from Bolshevik ideals or the use of apolitical modern state practices in the service of

socialism. This dissertation shows that while youth leaders were intensely interested in modern state practices, they made these practices into central elements of Soviet socialism. Through the Komsomol, youth became a resource for the state to guide along the uncertain and dangerous road to the future of communism. Reacting to domestic and international crises, Stalinist leaders created a system of state socialization for youth that would last until the fall of the Soviet Union.

Lenin’s Marxism*by Wolfgang Küttlertranslated by Loren Balhorn

Beginning in the early 1980s, Georges Labica worked towards a >renewal of Leninism<

against the dogma of Leninism that ruled in state socialism (1986, 123). He emphasized a

strand of thought in the Leninian tradition that avoids claims to a model character

seeking to raise >the empirical evidence of an exceptional historical situation to that of a

generality<, but instead seeks to serve as the foundation >of a political praxis<, which

works towards the realisation of a >communist revolution […] in conjunctures of a

necessarily extraordinary nature< (ibid.). He calls this type of renewing critique, which

works towards a constructive turn in the engagement with Lenin’s legacy, the >work of

the particular< (116). It requires historical concretization as well as critical evaluation of

Lenin’s >interventions< and their consequences for the further development of Marxism

(117).

The >warm stream, hopeful for change< (Mayer 1995, 300) that managed to survive,

against all odds, from Lenin to Gorbachev can nevertheless hardly conceal the fact that

Marxism >was in rapid retreat< (Hobsbawm 2011, 385) long before the emergence of

the >post-communist<, or rather >post-Soviet< situation (Haug 1993). This retreat could

also be observed in how >Soviet orthodoxy precluded any real Marxist analysis of what

had happened and was happening in Soviet society< (Hobsbawm 2011, 386). While

Marx’s analysis and critique of capitalism has retained its validity, reception of Lenin has

become even more overshadowed by Stalinism and its victims since 1989/91. Wolfgang

Ruge understands the tragedy of Lenin in that >he achieved a great amount, but what he

achieved did not correspond to that which he intended whatsoever<, and that his goal,

ultimately >overrun< by history, cost >millions of human lives< (2010, 398).

Nevertheless, the more Lenin is evaluated in light of the failure of Soviet state socialism

since 1989/91, including by Marxists and leftists, the more urgent a historical-critical

reconstruction of his views becomes.

This contribution first addresses the meaning of Lenin in terms of difference and

continuity with Marx on one hand, and in terms of the official Marxism-Leninism (ML)

canonised by Stalin on the other. Proceeding from the end of this epoch, the further

question of the general tendencies of development constituting the context in which

Lenin’s work and historical impact stand at the beginning of the 21st century, an epoch

characterised by conditions of global capitalism resting on the foundation of high-tech

forces of production, will also be addressed.

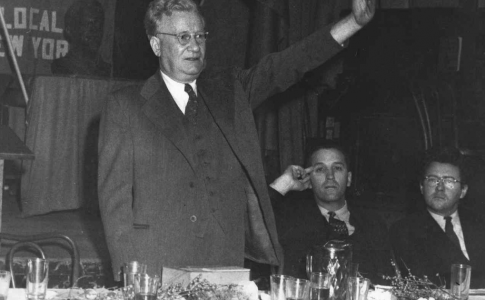

Canadian Trotskyism and the Legacy of James P. Cannon

photo James Patrick Cannon, SWP (Socialist Workers Party) local New York

Revolutionary socialists in Canada and the United States began organizing a revolutionary workers’ party around the same time. This occurred in the wake of World War I. The new organizations adopted the name Communist Party, in solidarity with the leading force in the Russian Revolution and in support of the leaders of the world’s first workers’ state, the Soviet Union. In Canada many members of the new party came from the Socialist Party of Canada and from the Social Democratic Party of Canada. In the United States, many of them came out of the Socialist Party of Eugene Debs and from the syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World, like James P. Cannon, who was a Wobbly before he became a Bolshevik. There were many internal tendencies and factions inside the new CPs, until Moscow stamped out internal democracy and required affiliates to the Comintern to expel all opponents of Joseph Stalin. In the USSR, many of Stalin’s political opponents were not just expelled or exiled; they were murdered. Historians say that Stalin killed more Communists than Adolf Hitler did.

Founding leaders of the Communist Party of Canada were Jack MacDonald and Maurice Spector. They worked closely with the leaders of the CP USA, like James P. Cannon and William Z. Foster. Spector and Cannon were delegates to the Sixth Congress of the Communist International in Moscow in 1928.

Spector accidentally got hold of a copy of Trotsky’s “Critique of the Draft Programme of the Communist International,” which criticized the position of Nikolai Bukharin and Joseph Stalin. It especially exposed the anti-Marxist theory of “socialism in one country.” This critique became a basis of the International Left Opposition. In a truly prophetic statement, Trotsky warned that if the Communist International adopted socialism in one country, it would inevitably lead to the nationalist and reformist degeneration of every Communist Party in the world. His prediction—which was ridiculed by the Stalinists at the time—was proved correct. Cannon reported what happened on that fateful occasion:

Through some slip-up in the apparatus in Moscow, which was supposed to be airtight, this document of Trotsky came into the translating room of the Comintern. It fell into the hopper, where they had a dozen or more translators and stenographers with nothing else to do. They picked up Trotsky’s document, translated it and distributed it to the heads of the delegations and the members of the program commission. So, lo and behold, it was laid in my lap, translated into English! Maurice Spector, a delegate from the Canadian party, and in somewhat the same frame of mind as myself, was also on the program commission and he got a copy. We let the caucus meetings and the Congress sessions go to the devil while we read and studied this document. Then I knew what I had to do, and so did he. Our doubts had been resolved. It was as clear as daylight that Marxist truth was on the side of Trotsky. We had a compact there and then—Spector and I—that we would come back home and begin a struggle under the banner of Trotskyism. (1)

Socialism in One Country: A Study of Pragmatism and Ideology in the Soviet 1920s

Michael Bensley

Table of Contents:

Introduction: p.3

I. War Communism: p.10

II. Lenin's Final Years: p.23

III. Interregnum: p.38

IV. Socialism in One Country as Theory: p.61

V. Socialism in One Country in Context: p.74

Conclusion: p.96

Bibliography: p.104

INTRODUCTION (EXCERPT)

Michael Bensley

Table of Contents:

Introduction: p.3

I. War Communism: p.10

II. Lenin's Final Years: p.23

III. Interregnum: p.38

IV. Socialism in One Country as Theory: p.61

V. Socialism in One Country in Context: p.74

Conclusion: p.96

Bibliography: p.104

INTRODUCTION (EXCERPT)

Bolshevik policy, upon seizure of power, had

associated itself with the concept of internationalism.

The principle was that the revolution should only

begin in Russia and that the western nations would,

in consequence, revolt as well. The economic aid

that western Europe was expected to donate to

their Russian partners was crucial. This was

especially true for Trotsky who, in his original capacity,

could not imagine any other course of action

other than his 'permanent revolution,' as first set out in

Results and Prospects (1906).5

In the

years which followed the First World War, the western nations

mainly stabilised. In consequence, the regime had

to abandon expectations of further insurrection

the question of whether a country could attempt to reach socialism alone.

The Russian situation,

primarily the backwardness of her industrial development, was another

pertinent issue to be

considered. Leon Trotsky, in an article in Pravda of May 1922 compared the

Soviet Union to a 'besieged fortress,' stating that during such a time of

political and economic isolation from the rest of the world, it was necessary

for the state to ensure unity at any cost.7

The political structures which

developed had ensured the dominance of the Bolsheviks as the only legitimate

party. A level of naivety existed intheir actions, as well as authoritarian

tendencies. Early policies such as 'War Communism' had been carried out in a

callous manner, with scant regard for the human cost. 'The descent into chaos'

which ensued, the excesses and trespasses into human life, had introduced a

framework which could be described as a 'Partocracy'.8

In 1921 the New Economic Policy was introduced. Whether this was a retreat

on the same lines as

the Brest-Livotsk treaty of 1918, (which withdrew the Bolsheviks from the

war against the Central

Powers), or more a pragmatic manoeuvre, is a question which shall be

explored. However, in Lenin's

last years of control, the party would go on to solidify its monopoly of

power. With such events as

the Social Revolutionary trials of 1922, the state had completed its path

towards authoritarianism. It

has been argued that the manner in which events which brought this on. The

idea being that Lenin had to operate in a difficult climate and had to enforce the

one-party state as a temporary measure to ensure the survival of the regime.

This would ultimately lead us to the conclusion that such concepts as 'Workers'

Democracy' reflected his original intentions, if the situation had not dictated

otherwise.9

Of course, historians who take ideology

as a primary factor in the way that the early Soviet Republic developed, have

commented on the economic 'retreat' of introducing NEP being countered with

political tightening.10

This would explain why Lenin had

dealt with his political opponents in this time in such a brutal fashion.

With Lenin's departure from leadership, due to a series of strokes, the

disunity of the leadership had

begun to unravel. As will be discussed in the course of this dissertation,

Stalin had been able to

secure a large number of positions in the state apparatus. His domination

of the bureaucracy

became a crucial factor. Through such organs as the Secretariat he had been

able to manipulate the

Party Congresses, so that the overwhelming majority of voting delegates came

in line with the

leadership, regardless of where the party cells placed their allegiance.

This had been of enormous

importance in the conflict with Trotsky's opposition.11

When Trotsky introduced the 'New Course' (1923), a criticism of the

inflated bureaucracy and the

excesses which had formed as a result of this, a debate began which would

see Stalin enter the field

of theory himself, with such works as The Foundations of Leninism (1924).

With Lenin's death, Stalin

was able to interpret freely many of the former master's ideas and twist

them in such a way that he

could use them to back up any attack. In the fight against 'Trotskyism',

the idea of 'socialism in one

country' came about. Initially, the idea of economic development within

isolated circumstances was

conceptualised by Nikolai Bukharin, but it would later be mentioned in a

pamphlet by Stalin, The

October Revolution and the Tactics of the Russian Communists (1924).12

To ascertain how it was that Stalin was able to take a few lines of Lenin's

previous works and

transform them in such a way as to develop his own body of ideas is crucial

in understanding the

discourse of events in the 1920s. The course of this work will therefore

examine both the context in

which 'socialism of one country' was conceived, and its relative value in

practice. It is easy to

espouse the view that his theory was 'a mere smoke-screen for a clash of

personal ambitions.'13 As

Isaac Deutscher, in his political biography Stalin reminds us, 'No doubt

the personal rivalries were a

strong element in it. But the historian who reduced the whole matter to

that would commit a

blatant mistake.'14 Indeed, as much as it could be argued that the whole

matter was simply to attack

Trotsky's 'permanent revolution' as a counter-thesis of sorts, it had other

properties.

Of course, Bukharin's view of building socialism in Russia alone was far

more geared towards slow

and considered development. By utilising NEP, the state could take a path

towards socialism which

would not have the disastrous outcomes which had become associated with

'War Communism'.15 It

will strike the reader that, for all the caution that Stalin would decree

in the mid-1920s, he ultimately

embarked on the 'revolution from above' and the 'great break.' The main

reasons why this had

occurred is the topic for the last chapter of this dissertation. Suffice it

is to say, the impact of varying

political and socio-economic crises, which occurred from 1926 onwards, had

a fundamental effect on

the regime and upon those who ruled it.

Nikolai Vavilov in the years of Stalin's ‘Revolution from Above’ (1929–1932)

Abstract

This paper examines new evidence from Russian archives to argue that Soviet geneticist and plant breeder, Nikolai I. Vavilov's fate was sealed during the ‘Cultural Revolution’ (‘Revolution from Above’) (1929–1932). This was several years before Trofim D. Lysenko, the Soviet agronomist and widely portrayed archenemy and destroyer of Vavilov, became a major force in Soviet science. During the ‘Cultural Revolution’ the Soviet leadership wanted to subordinate science and research to the task of socialist reconstruction. Vavilov, who was head of the Institute of Plant Breeding (VIR) and the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VASKhNIL), came under attack from the younger generation of researchers who were keen to transform biology into a proletarian science. The new evidence shows that it was during this period that Vavilov lost his independence to determine research strategies and manage personnel within his own institute. These changes meant that Lysenko, who had won Stalin's support, was able to gain influence and eventually exert authority over Vavilov. Based on the new evidence, Vavilov's arrest in 1940 after he criticized Lysenko's conception of Non-Mendelian genetics was just the final challenge to his authority. He had already experienced years of harassment that began before Lysenko gained a position of influence. Vavilov died in prison in 1943.

The Reintegration of the Russian Empire and the Bolshevik Views of "Russia":

The Case of the Moscow Party Organization

Author(s) Ikeda, Yoshiro

After the years of the civil war much of the former imperial territory appeared to be reintegrated by the Bolsheviks. The process of reintegration itself took the form of the conquest of the peripheries.6 But the notion of “Russia” remained ambiguous for the Bolshevik regime. In connection with this we cannot avoid Agurskii’s study on so-called national Bolshevism. According to him, in the years of the NEP, an emigrant ideology of national Bolshevism, which considered the Bolshevik regime as the only real political power able to reintegrate and develop the “one, indivisible Russia” and called on technocrats to support it, found resonance within the party. By tolerating and even promoting currents of Russian nationalism in culture and politics, the leaders of the party, and especially Stalin, caught up and introduced this ideology into the party policy for the consolidation of the legitimacy of the regime. Thus, Agurskii explained the intensive emergence of Russian nationalism in the USSR of the NEP era. The study of Agurskii is pioneering in making clear many aspects of the underground dialogue between the emigrant statist movement of the Change of Landmarks and the Bolshevik regime. However, if he assumes that the Bolshevik government tolerating the Russian nationalist currents in Soviet society, had been seeking reinforcement of the cultural and political hegemony of the Russian ethnicity (and judging from his attention to the writers whose main theme was the Russian peasantry, he seems to do so), then he is not correct. It seems that in 1920s and afterwards the Bolshevik regime had aimed not so much for the hegemony of ethnic Russians, as for the consolidation of a supra-ethnic entity. To make this matter clear, I will turn to the recent studies of the Bolshevik nationality policy in the 1920s and later. These studies had made clear that the 4 Here I depend on the argument of Anthony Smith that “the nation has come to blend two sets of dimensions, the one civic and territorial, the other ethnic and genealogical.” Anthony D. Smith, National Identity (Reno, 1991), p. 15. Especially on the “civic nation,” see, ibid., p. 116. 5 Sanborn, Drafting the Russian Nation, pp. 21-38; David Brandenberger, National Bolshevism: Stalinist Mass Culture and the Formation of Modern Russian National Identity, 1931-1956 (Cambridge, 2002), ch. 1.

The Case of the Moscow Party Organization

Author(s) Ikeda, Yoshiro

After the years of the civil war much of the former imperial territory appeared to be reintegrated by the Bolsheviks. The process of reintegration itself took the form of the conquest of the peripheries.6 But the notion of “Russia” remained ambiguous for the Bolshevik regime. In connection with this we cannot avoid Agurskii’s study on so-called national Bolshevism. According to him, in the years of the NEP, an emigrant ideology of national Bolshevism, which considered the Bolshevik regime as the only real political power able to reintegrate and develop the “one, indivisible Russia” and called on technocrats to support it, found resonance within the party. By tolerating and even promoting currents of Russian nationalism in culture and politics, the leaders of the party, and especially Stalin, caught up and introduced this ideology into the party policy for the consolidation of the legitimacy of the regime. Thus, Agurskii explained the intensive emergence of Russian nationalism in the USSR of the NEP era. The study of Agurskii is pioneering in making clear many aspects of the underground dialogue between the emigrant statist movement of the Change of Landmarks and the Bolshevik regime. However, if he assumes that the Bolshevik government tolerating the Russian nationalist currents in Soviet society, had been seeking reinforcement of the cultural and political hegemony of the Russian ethnicity (and judging from his attention to the writers whose main theme was the Russian peasantry, he seems to do so), then he is not correct. It seems that in 1920s and afterwards the Bolshevik regime had aimed not so much for the hegemony of ethnic Russians, as for the consolidation of a supra-ethnic entity. To make this matter clear, I will turn to the recent studies of the Bolshevik nationality policy in the 1920s and later. These studies had made clear that the 4 Here I depend on the argument of Anthony Smith that “the nation has come to blend two sets of dimensions, the one civic and territorial, the other ethnic and genealogical.” Anthony D. Smith, National Identity (Reno, 1991), p. 15. Especially on the “civic nation,” see, ibid., p. 116. 5 Sanborn, Drafting the Russian Nation, pp. 21-38; David Brandenberger, National Bolshevism: Stalinist Mass Culture and the Formation of Modern Russian National Identity, 1931-1956 (Cambridge, 2002), ch. 1.

New Revolutionary Agenda: The Interwar Japanese Left on the “Chinese Revolution”

Tatiana Linkhoeva, New York University

Abstract

To achieve socialist revolutions in Asia, the Third Communist International (Comintern)

recommended to Asian revolutionaries the strategy of a united front comprising the

proletariat and the national bourgeoisie, which would prioritize the anti-colonial and

anti-imperialist struggle. The early Japanese Communist Party (JCP) (1922–1926) resisted this

recommendation, which lumped together colonized India and semi-colonized China with the

only empire in Asia, Japan. The JCP insisted on the priority of the domestic national struggle,

arguing that without toppling the imperial government at home by means of a socialist

revolution, there could be no dismantling of Japanese imperialism and therefore no Chinese

Revolution. After the outbreak of Japanese aggression in China in 1927 (the first Shantung

intervention in May of that year) and the rise of popular nationalist support for the empire at

home, members of the Japanese Left recognized that they had failed to properly engage with

Japanese imperialism in Asia. Based on Comintern archives and the writings of leading

Japanese Communists, this article argues that, as a strategy to rebrand and redeem itself in the

new critical situation in Asia, the Japanese Left began to regard the Chinese Revolution as the

only path to liberation, not only for Asia but for Japan as well.

Keywords: Japanese Communism, Chinese Revolution, Comintern, Japanese imperialism

Tatiana Linkhoeva, New York University

Abstract

To achieve socialist revolutions in Asia, the Third Communist International (Comintern)

recommended to Asian revolutionaries the strategy of a united front comprising the

proletariat and the national bourgeoisie, which would prioritize the anti-colonial and

anti-imperialist struggle. The early Japanese Communist Party (JCP) (1922–1926) resisted this

recommendation, which lumped together colonized India and semi-colonized China with the

only empire in Asia, Japan. The JCP insisted on the priority of the domestic national struggle,

arguing that without toppling the imperial government at home by means of a socialist

revolution, there could be no dismantling of Japanese imperialism and therefore no Chinese

Revolution. After the outbreak of Japanese aggression in China in 1927 (the first Shantung

intervention in May of that year) and the rise of popular nationalist support for the empire at

home, members of the Japanese Left recognized that they had failed to properly engage with

Japanese imperialism in Asia. Based on Comintern archives and the writings of leading

Japanese Communists, this article argues that, as a strategy to rebrand and redeem itself in the

new critical situation in Asia, the Japanese Left began to regard the Chinese Revolution as the

only path to liberation, not only for Asia but for Japan as well.

Keywords: Japanese Communism, Chinese Revolution, Comintern, Japanese imperialism

The Soviet experiment with Pure Communism*

Introduction

In 1957, forty years after the Russian revolution, Michael Polanyi (HE IS THE RIGHT WING NEO CON BROTHER OF KARL POLANYI) summarized

the state of Soviet studies by pointing out that despite, or because of the fact

that “volume upon volume of excellent scholarship [was] rapidly accumulating

on the history of the Russian Revolution … The Revolution [was] about to be

quietly enshrined under a pyramid of monographs.” This condition continues

to persist even after seventy years of reflection upon one of the most fateful

events in political–economic history. Despite heroic efforts by Paul Craig

Roberts and Laszlo Szamuely to lift the Revolution from underneath the debris

of wood pulp, confusion still permeates historical discussion of the meaning of

the Soviet experience with Communism.4 “We have forgotten,” as Polyanyi

wrote, “what the Russian Revolution was about: that it set out to establish a

money-less industrial system, free from the chaotic and sordid automation of

the market and directed instead scientifically by one single comprehensive

plan.”5

The grand debate over the Soviet experience from 1918 to 1921 revolves

around whether the Bolsheviks followed policies that were ideological in origin

or were forced upon them by the necessity of civil war. If Bolshevik economics

was ideological, then Marxian socialism must confront the failure of its utopia

to achieve results that are even humane, let alone superior to capitalism. If it

was spawned by an emergency, then the Soviet experience from 1918 to 1921

does not provide any lesson for the economic assessment of socialism. (Some

recent authors wish to argue that the policies now known as “War Communism”

were produced by both ideology and emergency, and, as a result, they

fundamentally misunderstand the meaning of the Soviet experience with

socialism.)6 In order to evaluate these opposing interpretations, let me first lay

out points of agreement and conflict among those interpreters of the Soviet

experience with socialism who have established the two poles of the grand

debate......

Introduction

In 1957, forty years after the Russian revolution, Michael Polanyi (HE IS THE RIGHT WING NEO CON BROTHER OF KARL POLANYI) summarized

the state of Soviet studies by pointing out that despite, or because of the fact

that “volume upon volume of excellent scholarship [was] rapidly accumulating

on the history of the Russian Revolution … The Revolution [was] about to be

quietly enshrined under a pyramid of monographs.” This condition continues

to persist even after seventy years of reflection upon one of the most fateful

events in political–economic history. Despite heroic efforts by Paul Craig

Roberts and Laszlo Szamuely to lift the Revolution from underneath the debris

of wood pulp, confusion still permeates historical discussion of the meaning of

the Soviet experience with Communism.4 “We have forgotten,” as Polyanyi

wrote, “what the Russian Revolution was about: that it set out to establish a

money-less industrial system, free from the chaotic and sordid automation of

the market and directed instead scientifically by one single comprehensive

plan.”5

The grand debate over the Soviet experience from 1918 to 1921 revolves

around whether the Bolsheviks followed policies that were ideological in origin

or were forced upon them by the necessity of civil war. If Bolshevik economics

was ideological, then Marxian socialism must confront the failure of its utopia

to achieve results that are even humane, let alone superior to capitalism. If it

was spawned by an emergency, then the Soviet experience from 1918 to 1921

does not provide any lesson for the economic assessment of socialism. (Some

recent authors wish to argue that the policies now known as “War Communism”

were produced by both ideology and emergency, and, as a result, they

fundamentally misunderstand the meaning of the Soviet experience with

socialism.)6 In order to evaluate these opposing interpretations, let me first lay

out points of agreement and conflict among those interpreters of the Soviet

experience with socialism who have established the two poles of the grand

debate......

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=WAR+COMMUNISM

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=SOVIET+UNION

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=STATE+CAPITALISM

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=RUSSIAN+REVOLUTION

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=RUSSIA

SEE https://plawiuk.blogspot.com/search?q=COMMUNISM

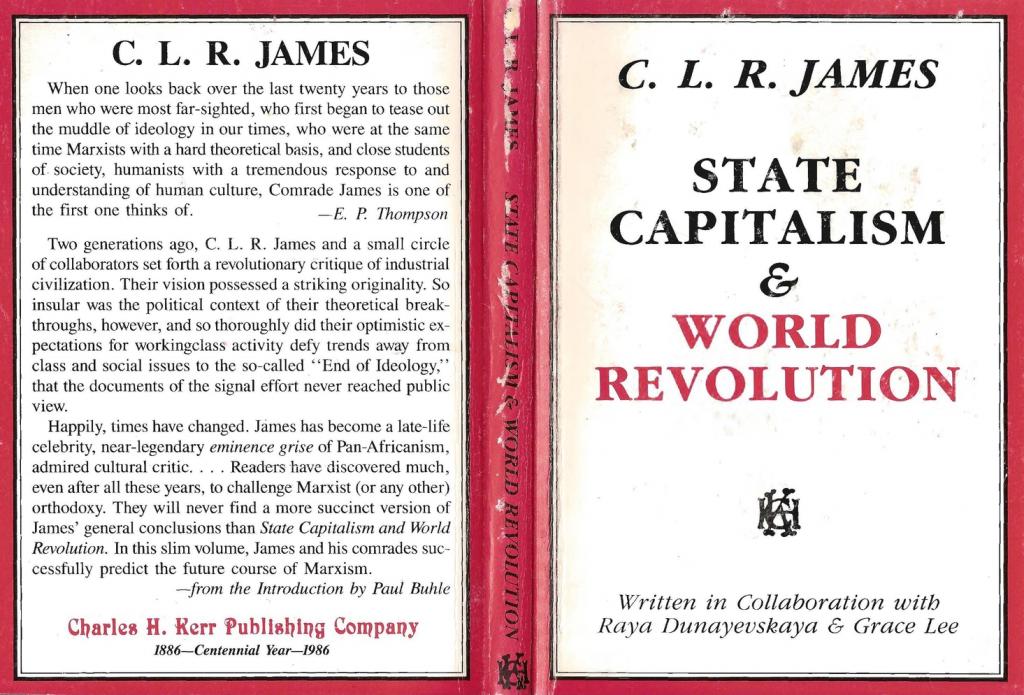

by R Dunayevskaya - Cited by 3 - Related articles

general conclusions than State Capitalism and World Revolution. I. In this slim ... The singular Raya Dunayevskaya, Russian-born intellectual and secretary to ...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)