Uber loses French case, driver declared employee

France's top civil court dealt ride-hailing giant Uber a setback on Wednesday with a key ruling that it had effectively employed one of its drivers.

Uber has long argued it is merely a platform linking self-employed drivers with riders, a model which allows for avoidance of certain taxes and social charges as well as paid vacations.

However that practice, which underpins the gig economy, has increasingly come under legal attack in many countries.

The French Court of Cassation ruled against Uber's appeal of a 2019 decision that a former driver who sued the firm effectively had a work contract.

The court found that Uber BV had control over the driver by his connection to the app which directs him to clients, and thus should not be considered an independent contractor but an employee.

"This is a first and it will impact all platforms inspired by Uber's model," said Fabien Masson, the lawyer for the former driver.

The ruling does not force Uber to automatically sign contracts, and drivers will have to go to court to obtain requalification as employees.

But for the estimated 150 Uber drivers who have already filed cases, "these drivers will benefit from this ruling", said Masson.

Another lawyer who represents a dozen Uber drivers, Kevin Mention, said the ruling will eventually put the gig economy model at risk in France as it clearly described practices that are common to all firms that use it.

"If they don't change their model today they are heading straight for the wall as it is certain qualification" for those who challenge their status as contractors.

Uber said the ruling missed many of the changes it has made.

"During the past two years we have made many changes that give drivers more control over how they use the app as well as better social protection," said a spokeswoman.

She said drivers choose Uber for the independence and flexibility it allows them and noted the Court of Cassation ruling contradicted its earlier decisions that said without an obligation to work there was no effective employment.

In the French case, the driver, who stopped working for Uber in 2016 after providing some 4,000 trips in under two years, sued to have his "commercial accord" reclassified as an employment contract.

He was seeking reimbursement for holidays and expenses as well as payment for "undeclared work" and unfair contract termination.

The former driver sued after Uber deactivated his account, "depriving him of the possibility to get new reservations", according to the court.

French court backs Uber driver in key gig-economy case (Update)

French court rules against Uber to class drivers as employees, not independent contractor

Issued on: 04/03/2020

French court rules against Uber to class drivers as employees, not independent contractor

Issued on: 04/03/2020

An advert for the Uber ride-sharing service is seen on a bus stop in Paris, France, March 11, 2016. © Charles Platiau, REUTERS

Text by:NEWS WIRES

France’s top civil court dealt ride-hailing giant Uber a setback on Wednesday with a ruling that it had effectively employed one of its drivers.

Uber has long argued that it is merely a platform linking self-employed drivers with riders, a model which allows it to avoid paying certain taxes and social charges as well as provide paid vacations.

However that practice, which underpins the gig economy, has increasingly come under legal attack in many countries.

In Wednesday’s ruling, the French Court of Cassation rejected Uber’s appeal against a 2019 decision that found a former driver who sued the firm effectively had a work contract.

The court found that Uber BV had control over the driver by his connection to the app which directs him to clients, and thus should not be considered an independent contractor but an employee.

“This is a first and it will impact all platforms inspired by Uber’s model,” said Fabien Masson, the lawyer for the former driver.

The ruling does not force Uber to automatically sign contracts, and drivers will be forced to go to court to obtain requalification as employees.

But for the estimated 150 Uber drivers who have already filed cases, “these drivers will benefit from this ruling”, said Masson.

Gig economy at risk

Another lawyer who represents a dozen Uber drivers, Kevin Mention, said the ruling will eventually put the gig economy model at risk in France as it clearly described practices that are common to all firms that use it.

“If they don’t change their model today they are heading straight for the wall as it is certain qualification” for those who challenge their status as contractors.

Uber, for its part, said the ruling missed many of the changes it has made.

“During the past two years we have made many changes that give drivers more control over how they use the app as well as better social protection,” said a spokeswoman.

She said drivers choose Uber for the independence and flexibility it allows them and noted the Court of Cassation ruling contradicted its earlier decisions that said without an obligation to work their was not effective employment.

In the French case, the driver, who stopped working for Uber in 2016 after providing some 4,000 trips in under two years, sued to have his “commercial accord” reclassified as an employment contract.

He was seeking reimbursement for holidays and expenses as well as payment for “undeclared work” and unfair contract termination.

The former driver sued after Uber deactivated his account, “depriving him of the possibility to get new reservations”, according to the court.

(AFP)

Text by:NEWS WIRES

France’s top civil court dealt ride-hailing giant Uber a setback on Wednesday with a ruling that it had effectively employed one of its drivers.

Uber has long argued that it is merely a platform linking self-employed drivers with riders, a model which allows it to avoid paying certain taxes and social charges as well as provide paid vacations.

However that practice, which underpins the gig economy, has increasingly come under legal attack in many countries.

In Wednesday’s ruling, the French Court of Cassation rejected Uber’s appeal against a 2019 decision that found a former driver who sued the firm effectively had a work contract.

The court found that Uber BV had control over the driver by his connection to the app which directs him to clients, and thus should not be considered an independent contractor but an employee.

“This is a first and it will impact all platforms inspired by Uber’s model,” said Fabien Masson, the lawyer for the former driver.

The ruling does not force Uber to automatically sign contracts, and drivers will be forced to go to court to obtain requalification as employees.

But for the estimated 150 Uber drivers who have already filed cases, “these drivers will benefit from this ruling”, said Masson.

Gig economy at risk

Another lawyer who represents a dozen Uber drivers, Kevin Mention, said the ruling will eventually put the gig economy model at risk in France as it clearly described practices that are common to all firms that use it.

“If they don’t change their model today they are heading straight for the wall as it is certain qualification” for those who challenge their status as contractors.

Uber, for its part, said the ruling missed many of the changes it has made.

“During the past two years we have made many changes that give drivers more control over how they use the app as well as better social protection,” said a spokeswoman.

She said drivers choose Uber for the independence and flexibility it allows them and noted the Court of Cassation ruling contradicted its earlier decisions that said without an obligation to work their was not effective employment.

In the French case, the driver, who stopped working for Uber in 2016 after providing some 4,000 trips in under two years, sued to have his “commercial accord” reclassified as an employment contract.

He was seeking reimbursement for holidays and expenses as well as payment for “undeclared work” and unfair contract termination.

The former driver sued after Uber deactivated his account, “depriving him of the possibility to get new reservations”, according to the court.

(AFP)

Craspedotropis gretathunbergae. Taxon Expeditions

Craspedotropis gretathunbergae. Taxon Expeditions Taxon Expeditions participant J.P. Lim collecting snails. Taxon Expeditions - Pierre Escoubas

Taxon Expeditions participant J.P. Lim collecting snails. Taxon Expeditions - Pierre Escoubas

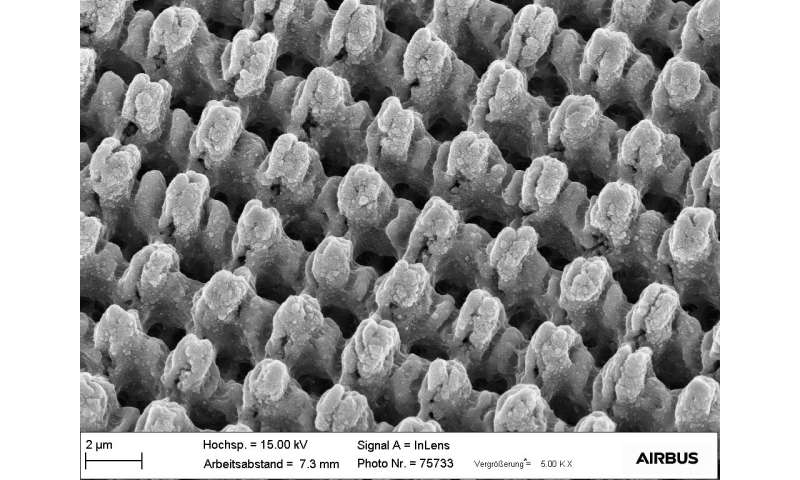

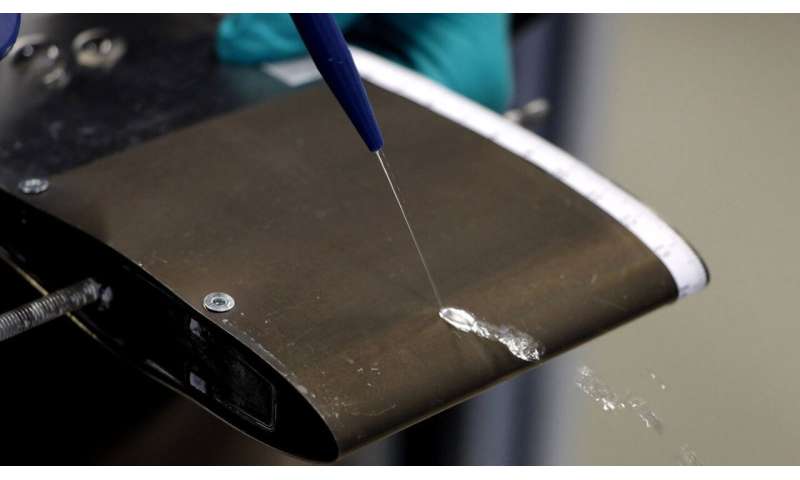

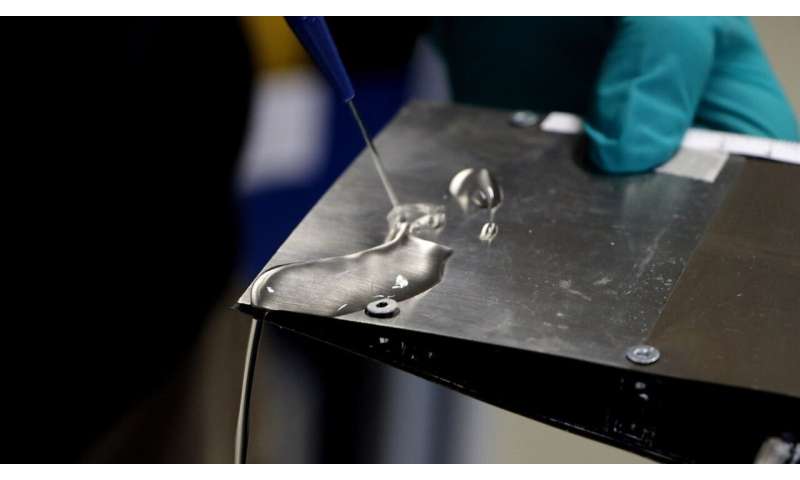

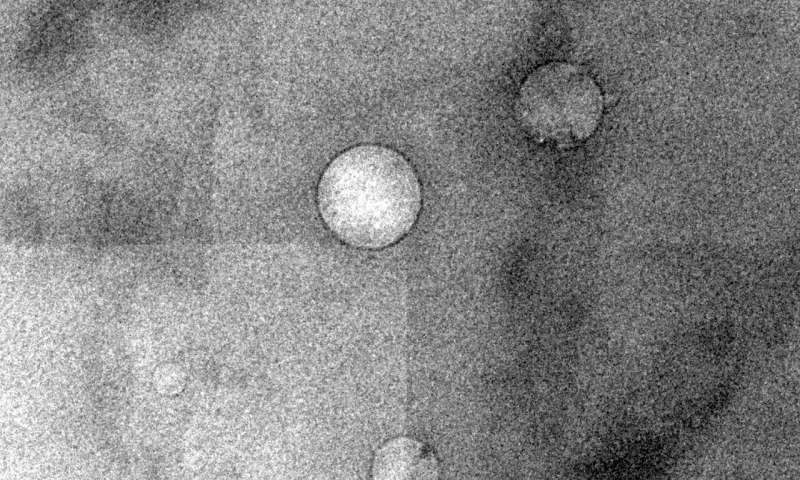

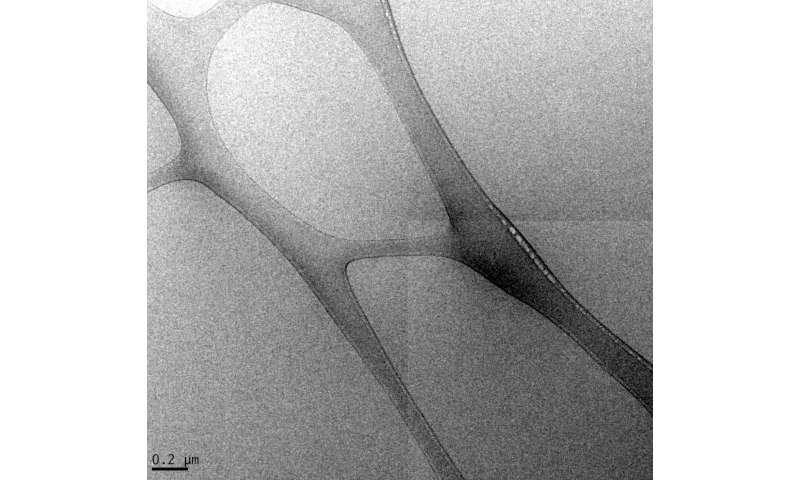

High-salinity brine mixed with crude oil does not appear to emulsify like low-salinity brine does, according to Rice University engineers studying the phenomenon. Their results have implications for enhanced oil recovery. Credit: Wenhua Guo/Rice University

High-salinity brine mixed with crude oil does not appear to emulsify like low-salinity brine does, according to Rice University engineers studying the phenomenon. Their results have implications for enhanced oil recovery. Credit: Wenhua Guo/Rice University