by Colin Poitras, Yale University

Credit: Krystal Pollitt

Whether it comes from second-hand cigarette smoke, motor vehicle exhaust, building materials or the fumes from household cleaning supplies, toxic air is all around us.

Doctors and scientists are notably concerned about air pollution as it ranks among the top 10 global health risks associated with non-communicable diseases. Organic air pollutants have been shown to contribute to respiratory and cardiac disease as well as reproductive and neurobehavioral problems.

Yet measuring personal exposure levels remains tricky.

Some scientists use expensive air monitors placed in strategic locations. Others employ bulky backpacks loaded with expensive filters and pumps. Wearable detection badges are useful for people working dangerous jobs. Yet each approach has its own limitations, from time consuming laboratory analysis to high risks of unrelated environmental contamination.

Yale School of Public Health Assistant Professor Krystal Pollitt is introducing a new option–a lightweight, unobtrusive, wearable air pollutant sampler she calls the Fresh Air wristband.

During initial testing, the device reliably collected and retained air pollutant molecules over time, allowing for easy analysis and scale-up to monitor large segments of a population.

While the wristband was initially designed to detect air pollutants, in light of the current pandemic, Pollitt is exploring its potential use in monitoring exposure to small airborne pathogens such as coronavirus. She is working with Jordan Peccia, the Thomas E. Golden Jr. professor of chemical and environmental engineering, and Dr. Jodi Sherman, associate professor of anesthesiology and of epidemiology (environmental health sciences), in conducting a field test of the wristbands' capabilities with the help of health care providers at Yale New Haven Hospital.

In a study recently published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters, Pollitt and a team of YSPH graduate students used the Fresh Air wristband to investigate air pollutant exposure in a group of school-aged children in Springfield, Massachusetts. In this first large scale test of the device, the wristbands detected elevated levels of exposure to pyrene, nitrogen dioxide and other pollutants among children with asthma, those living in certain housing conditions and those taking cars rather than buses to school, illustrating the wristband's potential applications.

Whether it comes from second-hand cigarette smoke, motor vehicle exhaust, building materials or the fumes from household cleaning supplies, toxic air is all around us.

Doctors and scientists are notably concerned about air pollution as it ranks among the top 10 global health risks associated with non-communicable diseases. Organic air pollutants have been shown to contribute to respiratory and cardiac disease as well as reproductive and neurobehavioral problems.

Yet measuring personal exposure levels remains tricky.

Some scientists use expensive air monitors placed in strategic locations. Others employ bulky backpacks loaded with expensive filters and pumps. Wearable detection badges are useful for people working dangerous jobs. Yet each approach has its own limitations, from time consuming laboratory analysis to high risks of unrelated environmental contamination.

Yale School of Public Health Assistant Professor Krystal Pollitt is introducing a new option–a lightweight, unobtrusive, wearable air pollutant sampler she calls the Fresh Air wristband.

During initial testing, the device reliably collected and retained air pollutant molecules over time, allowing for easy analysis and scale-up to monitor large segments of a population.

While the wristband was initially designed to detect air pollutants, in light of the current pandemic, Pollitt is exploring its potential use in monitoring exposure to small airborne pathogens such as coronavirus. She is working with Jordan Peccia, the Thomas E. Golden Jr. professor of chemical and environmental engineering, and Dr. Jodi Sherman, associate professor of anesthesiology and of epidemiology (environmental health sciences), in conducting a field test of the wristbands' capabilities with the help of health care providers at Yale New Haven Hospital.

In a study recently published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters, Pollitt and a team of YSPH graduate students used the Fresh Air wristband to investigate air pollutant exposure in a group of school-aged children in Springfield, Massachusetts. In this first large scale test of the device, the wristbands detected elevated levels of exposure to pyrene, nitrogen dioxide and other pollutants among children with asthma, those living in certain housing conditions and those taking cars rather than buses to school, illustrating the wristband's potential applications.

Credit: Yale University

"These results show the potential utility of the Fresh Air wristband as a wearable personal air pollutant sampler capable of assessing exposure among vulnerable populations, especially young children and pregnant women," said Pollitt, who holds joint appointments in the YSPH Department of Environmental Health Sciences and the Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering in the Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science.

So how does it work? The Fresh Air wristband looks like a fashionable Swatch wristwatch with a quarter-sized plastic air sampler embedded where the watch face would normally be. Pop open the cover and inside is a small foam pad coated with a chemical (triethanolamine) that reacts with nitrogen dioxide, an air pollutant that is a byproduct of burned fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas. The device also contains a small sorbent bar made of a silicone-based polymer (polydimethylsiloxane). The bar collects volatile organic compounds (the chemicals found in such things as glue, pesticides, cigarettes, and solvents) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) like phenanthrene and chrysene, which can be found in car exhaust, cigarette smoke, wood smoke and fumes from cooking. The Fresh Air wristband is particularly good at capturing heavier molecular compounds and retaining them over multiple days.

The sampling pad and sorbent bars contained in the wristband can be easily inserted and removed, especially when testing personal exposures over time. As samples are collected, the wristband materials are placed in airtight amber glass vials for preservation until chemical analysis. Rather than extracting the samples using solvents (a labor-intensive lab process), Pollitt says her device allows for faster and easier analysis using mass spectrometry to get a detailed chemical profile of a person's chemical exposures.

In the Springfield study, 33 children ages 12 and13 wore the wristbands for 5 days, only taking them off at night where they were left next to their beds. The participants were predominately girls (69%) and a third had physician-diagnosed asthma.

"These results show the potential utility of the Fresh Air wristband as a wearable personal air pollutant sampler capable of assessing exposure among vulnerable populations, especially young children and pregnant women," said Pollitt, who holds joint appointments in the YSPH Department of Environmental Health Sciences and the Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering in the Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science.

So how does it work? The Fresh Air wristband looks like a fashionable Swatch wristwatch with a quarter-sized plastic air sampler embedded where the watch face would normally be. Pop open the cover and inside is a small foam pad coated with a chemical (triethanolamine) that reacts with nitrogen dioxide, an air pollutant that is a byproduct of burned fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas. The device also contains a small sorbent bar made of a silicone-based polymer (polydimethylsiloxane). The bar collects volatile organic compounds (the chemicals found in such things as glue, pesticides, cigarettes, and solvents) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) like phenanthrene and chrysene, which can be found in car exhaust, cigarette smoke, wood smoke and fumes from cooking. The Fresh Air wristband is particularly good at capturing heavier molecular compounds and retaining them over multiple days.

The sampling pad and sorbent bars contained in the wristband can be easily inserted and removed, especially when testing personal exposures over time. As samples are collected, the wristband materials are placed in airtight amber glass vials for preservation until chemical analysis. Rather than extracting the samples using solvents (a labor-intensive lab process), Pollitt says her device allows for faster and easier analysis using mass spectrometry to get a detailed chemical profile of a person's chemical exposures.

In the Springfield study, 33 children ages 12 and13 wore the wristbands for 5 days, only taking them off at night where they were left next to their beds. The participants were predominately girls (69%) and a third had physician-diagnosed asthma.

Key findings included:

Girls had higher levels of pollutant exposure than boys.

Children with asthma had elevated exposures to pyrene and acenapthylene, two aromatic hydrocarbons which could exacerbate breathing problems.

Children living in houses with gas stoves had increased exposure to certain pollutants compared to those with electric stoves.

Children in homes using stove ventilation hoods had lower exposure levels of nitrogen dioxide compared to homes without ventilation hoods.

Children who traveled by car to school had increased levels of aromatic hydrocarbons compared to their peers who walked or traveled by bus.

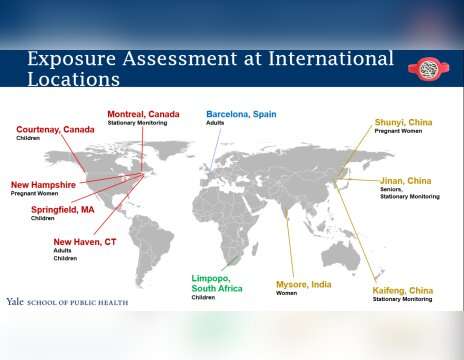

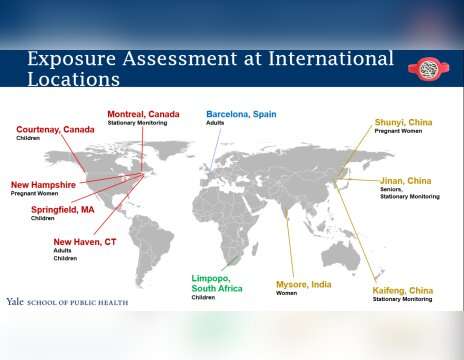

The research team has expanded its work globally and is currently using hundreds of the Fresh Air wristbands to explore chemical exposures among pregnant women, seniors and other demographics in other countries.

Pollitt, who invented the device, is currently in the process of filing for a patent. Students from her research group, Elizabeth Lin, Jeremy Koelmel, Alex Chen, and Anmol Arora, are forming a start-up company to make the product available to the public. The group was a recent finalist in this year's Startup Yale innovation and entrepreneurship competition. They have also received multiple start-up grants from the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale and InnovateHealth Yale.

Pollitt envisions many important uses for the Fresh Air wristband.

"We see the Fresh Air wristband being an important tool in future epidemiological studies and potentially also for citizen science," said Pollitt. "It can provide insight into a single individual's pollutant profile and be scaled-up to collect data across large populations, which can help us better understand the environmental risk factors for disease."

More information: Elizabeth Z. Lin et al. The Fresh Air Wristband: A Wearable Air Pollutant Sampler, Environmental Science & Technology Letters (2020).

Journal information: Environmental Science & Technology Letters

Provided by Yale University

Wristband samplers show similar chemical exposure across three continents

by Chris Branam, Oregon State University APRIL 22, 2019

Oregon State University

To assess differences and trends in personal chemical exposure, Oregon State University researchers deployed chemical-sampling wristbands to individuals on three continents.

After they analyzed the wristbands that were returned, they found that no two wristbands had identical chemical detections. But the same 14 chemicals were detected in more than 50 percent of the wristbands returned from the United States, Africa and South America.

"Whether you are a farmworker in Senegal or a preschooler in Oregon, you might be exposed to those same 14 chemicals that we detected in over 50 percent of the wristbands," said Holly Dixon, a doctoral candidate at Oregon State and the study's lead author.

The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, is published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

This study demonstrates that the wristbands, which absorb chemicals from the air and skin, are an excellent screening tool for population exposures to organic chemicals, said Kim Anderson, an OSU environmental chemist and leader of the research team. It's notable, she said, that most of the 14 common chemicals aren't heavily studied.

"Some of these are not on our radar, yet they represent an enormous exposure," she said. "If we want to understand the impact of chemical exposures, this was very enlightening."

Anderson and her team invented the wristband samplers several years ago. They have been used in other studies, including one that measured Houston residents' exposure in floodwaters after Hurricane Harvey.

In this study, 242 volunteers from 14 communities in four countries—the United States, Senegal, South Africa and Peru—wore a total of 262 wristbands. The Houston residents were included in the study.

Oregon State researchers analyzed the wristbands for 1,530 unique organic chemicals. The number of chemical detections ranged from four to 43 per wristband, with 191 different chemicals detected. And 1,339 chemicals weren't detected in any wristband. They detected 36 chemicals in common in the United States, South America and Africa.

Because the wristbands don't measure chemical levels, the study authors didn't make any conclusions regarding health risks posed by the wearers of wristbands. But certain levels of chemical exposures are associated with adverse health outcomes.

For example, exposure to certain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) has been associated with cancer, self-regulatory capacity issues, low birth weight and respiratory distress. These chemicals were found in many of the wristbands.

Exposure to specific flame retardants, which were found in wristbands in the U.S. and South America, has been associated with cancer, neurotoxicity and cardiotoxicity.

And exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) has been linked to health effects such as low semen quality, adverse pregnancy outcomes and endocrine-related cancers.

The researchers detected 13 potential EDCs in more than half of all the wristbands.

Other notable findings in the study included:

To assess differences and trends in personal chemical exposure, Oregon State University researchers deployed chemical-sampling wristbands to individuals on three continents.

After they analyzed the wristbands that were returned, they found that no two wristbands had identical chemical detections. But the same 14 chemicals were detected in more than 50 percent of the wristbands returned from the United States, Africa and South America.

"Whether you are a farmworker in Senegal or a preschooler in Oregon, you might be exposed to those same 14 chemicals that we detected in over 50 percent of the wristbands," said Holly Dixon, a doctoral candidate at Oregon State and the study's lead author.

The study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, is published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

This study demonstrates that the wristbands, which absorb chemicals from the air and skin, are an excellent screening tool for population exposures to organic chemicals, said Kim Anderson, an OSU environmental chemist and leader of the research team. It's notable, she said, that most of the 14 common chemicals aren't heavily studied.

"Some of these are not on our radar, yet they represent an enormous exposure," she said. "If we want to understand the impact of chemical exposures, this was very enlightening."

Anderson and her team invented the wristband samplers several years ago. They have been used in other studies, including one that measured Houston residents' exposure in floodwaters after Hurricane Harvey.

In this study, 242 volunteers from 14 communities in four countries—the United States, Senegal, South Africa and Peru—wore a total of 262 wristbands. The Houston residents were included in the study.

Oregon State researchers analyzed the wristbands for 1,530 unique organic chemicals. The number of chemical detections ranged from four to 43 per wristband, with 191 different chemicals detected. And 1,339 chemicals weren't detected in any wristband. They detected 36 chemicals in common in the United States, South America and Africa.

Because the wristbands don't measure chemical levels, the study authors didn't make any conclusions regarding health risks posed by the wearers of wristbands. But certain levels of chemical exposures are associated with adverse health outcomes.

For example, exposure to certain polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) has been associated with cancer, self-regulatory capacity issues, low birth weight and respiratory distress. These chemicals were found in many of the wristbands.

Exposure to specific flame retardants, which were found in wristbands in the U.S. and South America, has been associated with cancer, neurotoxicity and cardiotoxicity.

And exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) has been linked to health effects such as low semen quality, adverse pregnancy outcomes and endocrine-related cancers.

The researchers detected 13 potential EDCs in more than half of all the wristbands.

Other notable findings in the study included:

Consumer product-related chemicals and phthalates—a group of chemicals found in plastics and vinyl—were a high percentage of chemical detections across all study locations.

U.S. children—11 years old or younger—had the highest percentage of flame-retardant detections compared with all other participants.

Wristbands worn in the Houston area immediately after Hurricane Harvey had the highest mean number of chemical detections—28—compared with other study locations, where the means ranged from 10-25.

Flame retardants were not detected in any wristbands in Africa. The absence of flame retardants in Senegal and South Africa wristbands may reflect a difference in flammability protection standards, housing materials and/or furniture used in certain Africa communities compared with communities in the U.S. and South America.

Toxicological and epidemiological studies often focus on one chemical or chemical class, yet people are exposed to complex chemical mixtures, rather than to a single chemical or an individual chemical class. The results reveal common chemical mixtures across several communities that can be prioritized for future study, Dixon said.

The study authors noted two significant limitations. They relied on a convenience sample of volunteers and did not randomly recruit participants, so the chemical exposures they reported may not be representative of all chemical exposures in the 14 communities.

Also, deployment length varied depending on the specific project. But they didn't detect a difference in the number of chemicals detected based on how long a participant wore a wristband.

Explore further

More information: Holly M. Dixon et al, Discovery of common chemical exposures across three continents using silicone wristbands, Royal Society Open Science (2019).

Journal information: Royal Society Open Science

Provided by Oregon State University