Who politicized the environment and climate change?

February 1, 2016

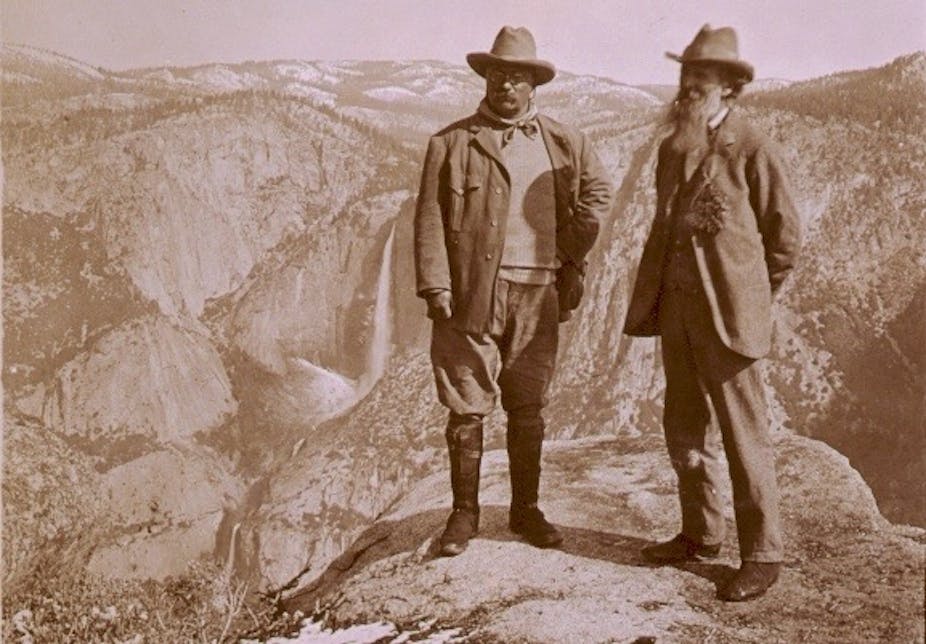

Protector in chief: Theodore Roosevelt with conservationist John Muir at Yosemite in 1906. U.S. Library of Congress

An environmental activist friend of mine recently shook her head and marveled at the extraordinary accomplishments of the last several months. “Still lots of work to be done,” she said. “But wow! This has been an epic period for environmentalists!”

From the rejection of the Keystone pipeline to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change (COP21), “epic” may be an apt descriptor for someone who is an environmentalist.

However, nothing galvanizes opposing forces to action better than significant wins by their foes. And 2016 appears to promise that environmental issues – particularly climate change – will be more politicized than ever before.

It wasn’t always this way.

By and large, environmental action since the 1960s proceeded in the U.S. in a bipartisan fashion, emphasizing issues of human health and resource conservation. That’s no longer true: almost by default, the Democratic Party stands largely alone, rather than together with the Republican Party, to uphold the ethic that environmental protection is a united, American common interest.

How have we gotten to a point where the environment has become such a partisan issue?

From Teddy R. to Reagan

The intellectual roots of American environmentalism are most often traced back to the 19th-century ideas of Romanticism and Transcendentalism from thinkers such as Henry David Thoreau. These philosophical and aesthetic ideas grew into initiatives for preserving the first national parks and monuments, an effort closely associated with Theodore Roosevelt. By the close of the 19th century, a combination of resource exploitation and increasing leisure led to a series of conservation efforts, such as protection of birds from feather hunters, which were often led by wealthy women.

Today’s environmentalism clearly harks back to these origins with aspects of being a social movement that seeks clear political outcomes, including regulation and government action. But much of what became known as the “modern environmental movement” originally coalesced around groups that formed under the influence of 1960s radicalism. The large oil spill in Santa Barbara, California in 1969 provided some of the impetus for landmark environmental laws signed by Nixon, including the Clean Air Act, which he signed December 31, 1970. National Archives

The large oil spill in Santa Barbara, California in 1969 provided some of the impetus for landmark environmental laws signed by Nixon, including the Clean Air Act, which he signed December 31, 1970. National Archives

The biggest impact of these organizations, though, came during the later 1960s and 1970s, when their membership skyrocketed with large numbers of the concerned, but not-so-radical, middle class. Through the formation of “nongovernment organizations” (NGOs), ranging widely from the Audubon Society to the Sierra Club, Americans found a mechanism through which they could demand a political response to environmental problems from lawmakers.

During the 1970s and 1980s, NGOs often initiated the call for specific policies and then lobbied members of Congress to create legislation. Such bipartisan action included clean water laws that restored Lake Erie and Ohio’s Cuyahoga River or responded to dramatic events such as the Santa Barbara Oil Spill in 1969.

An environmental activist friend of mine recently shook her head and marveled at the extraordinary accomplishments of the last several months. “Still lots of work to be done,” she said. “But wow! This has been an epic period for environmentalists!”

From the rejection of the Keystone pipeline to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change (COP21), “epic” may be an apt descriptor for someone who is an environmentalist.

However, nothing galvanizes opposing forces to action better than significant wins by their foes. And 2016 appears to promise that environmental issues – particularly climate change – will be more politicized than ever before.

It wasn’t always this way.

By and large, environmental action since the 1960s proceeded in the U.S. in a bipartisan fashion, emphasizing issues of human health and resource conservation. That’s no longer true: almost by default, the Democratic Party stands largely alone, rather than together with the Republican Party, to uphold the ethic that environmental protection is a united, American common interest.

How have we gotten to a point where the environment has become such a partisan issue?

From Teddy R. to Reagan

The intellectual roots of American environmentalism are most often traced back to the 19th-century ideas of Romanticism and Transcendentalism from thinkers such as Henry David Thoreau. These philosophical and aesthetic ideas grew into initiatives for preserving the first national parks and monuments, an effort closely associated with Theodore Roosevelt. By the close of the 19th century, a combination of resource exploitation and increasing leisure led to a series of conservation efforts, such as protection of birds from feather hunters, which were often led by wealthy women.

Today’s environmentalism clearly harks back to these origins with aspects of being a social movement that seeks clear political outcomes, including regulation and government action. But much of what became known as the “modern environmental movement” originally coalesced around groups that formed under the influence of 1960s radicalism.

The large oil spill in Santa Barbara, California in 1969 provided some of the impetus for landmark environmental laws signed by Nixon, including the Clean Air Act, which he signed December 31, 1970. National Archives

The large oil spill in Santa Barbara, California in 1969 provided some of the impetus for landmark environmental laws signed by Nixon, including the Clean Air Act, which he signed December 31, 1970. National ArchivesThe biggest impact of these organizations, though, came during the later 1960s and 1970s, when their membership skyrocketed with large numbers of the concerned, but not-so-radical, middle class. Through the formation of “nongovernment organizations” (NGOs), ranging widely from the Audubon Society to the Sierra Club, Americans found a mechanism through which they could demand a political response to environmental problems from lawmakers.

During the 1970s and 1980s, NGOs often initiated the call for specific policies and then lobbied members of Congress to create legislation. Such bipartisan action included clean water laws that restored Lake Erie and Ohio’s Cuyahoga River or responded to dramatic events such as the Santa Barbara Oil Spill in 1969.

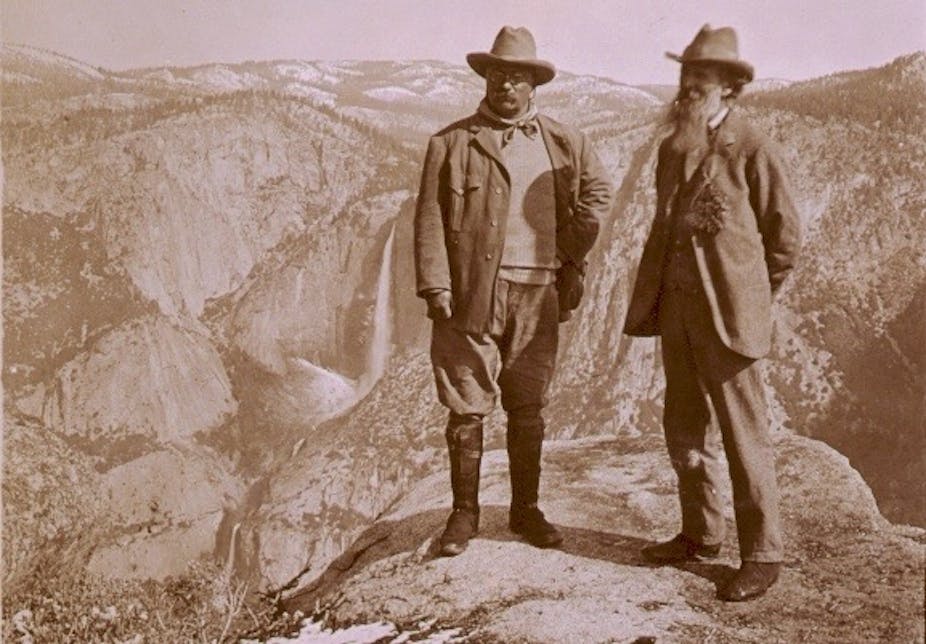

The nuclear power accident at Three Mile Island in 1979 fueled an antinuclear protest, a major concern of many environmentalists. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

The nuclear power accident at Three Mile Island in 1979 fueled an antinuclear protest, a major concern of many environmentalists. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)Republican and Democratic presidents of this era signed laws that had begun with grassroots demands for environmental action. Environmental issues, whether they were the effects of acid rain or the ozone hole, had become a prime concern in the political arena. Indeed, by the 1980s, NGOs had created a new political and legal battlefield as each side of environmental arguments sought to lobby lawmakers.

These gains by environmentalists had a ripple effect politically. In “A Climate of Crisis,” historian Patrick Allitt describes the opposition to environmentalism that emerged as a result of the bipartisan action on environment in the 1970s.

In particular, he describes the “anti-environmental” response manifested in policies of President Ronald Reagan, who slowed efforts to limit private development on public lands and set out to shrink the responsibilities of the federal government.

Antiregulation

Today, portions of this backlash appear to inform the views of candidates in the 2016 Republican presidential primary who reiterate the libertarian belief that it’s best to severely limit government regulation of the environment.

And compared to the cooperative vision of past leaders including President Teddy Roosevelt and Congressman John Saylor, who fought in the 1960s for wilderness and scenic river legislation, the Republican environmental mandate of the past appears today to be stymied.

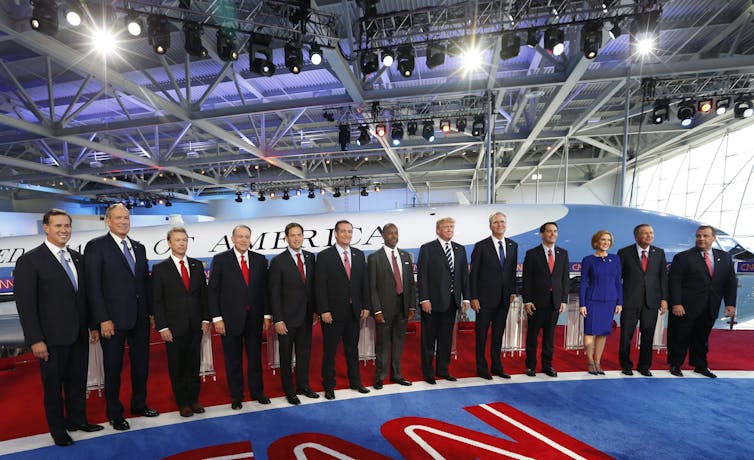

Climate change and environmental issues have barely come up in presidential debates, with candidates typically complaining that environment regulations will harm the economy. Mario Anzuoni/Reuters

Climate change and environmental issues have barely come up in presidential debates, with candidates typically complaining that environment regulations will harm the economy. Mario Anzuoni/ReutersRepublican presidential candidate Senator Ted Cruz, for example, tapped into this spirit when in December 2015 he held a three-hour “hearing” titled “Data or Dogma? Promoting Open Inquiry in the Debate over the Magnitude of Human Impact on Climate Change” (which technically was convened by the science panel of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation that he chairs).

Prior to his hearing on the topic, climate change had been little discussed at the party’s presidential debates; however, Cruz proclaimed that the “accepted science” proving climate change was actually a “religion” being forced on the American public by “monied interests.”

By contrast, Democrats stress the term “common sense” and appear more than content to allow their party to become the primary bastion for environmental concern. Hillary Clinton, as the likely Democratic presidential candidate, has often been publicly ahead of the Obama administration on environmental issues.

For instance, when in early 2015 Obama approved the expansion of Arctic drilling, Clinton openly opposed it. Also, Clinton was openly against the Keystone pipeline project long before Obama definitively rejected it.

In both Keystone and Arctic drilling, Obama allowed the issues a long and very public vetting process that has revealed a powerful, broad-based environmental lobby. NGOs such as 350.org and others have demonstrated a willingness for activist demonstrations, particularly due to a deep base of support for issues such as climate change and sustainable energy.

Republican candidates seem prepared to relent possible compromise on environmental questions in order to appeal to a special interest faction of their party. Overall, though, Gallup polling demonstrates broad-based support for environmental issues, including a solid 46 percent favoring protecting the environment over economic development.

Climate change worsens the political divide

Going forward, the most revealing flashpoint on issues related to the environment is likely to be climate change, particularly after the historic Paris Agreement of December 2015.

Global warming first made front page news in the 1980s when NASA scientist James Hansen testified to the Senate. Then in 2007, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) made history by specifying the connection between temperature rise and human activity with “very high confidence.”

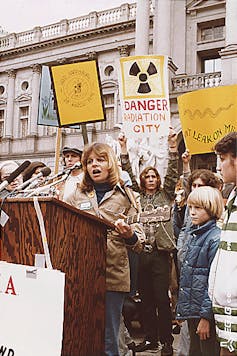

An emerging political force: activists for action on climate change and sustainable energy. Steve Rhodes/flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

An emerging political force: activists for action on climate change and sustainable energy. Steve Rhodes/flickr, CC BY-NC-NDIn its relation to environmentalism, climate change represents a clear expansion of thinking. While local issues such as oil spills and toxic waste remain concerns, climate change clarified the possible planet-changing extent of the human impact. As a concept, it has had time to percolate through human culture so that today we are most concerned with issues of “mitigation” and “adaptation” – managing or dealing with implications.

In each case, these responses to climate change involve plans for regulations to, for example, limit carbon emissions. In response to the increasing call for structural changes to our economy and society, contrary voices (such as that of Cruz) have found traction by saying mitigation efforts will undercut economic development and, in general, disrupt our everyday lives.

Not surprisingly, concrete mitigation efforts, such as discussions of “cap and trade” legislation to curb greenhouse gas emissions and international pacts such as COP21, have also spurred panicked responses among those destined to be impacted by the new thinking. For instance, coal companies and a number of states openly fight efforts by the EPA to monitor and regulate CO2 as a pollutant.

So who politicized the environment? Ultimately, voters have.

By tying environmental issues such as climate change to our system of laws and regulations at the end of the 1960s, Americans permanently chained these concerns to political vagaries in the future. Politics is now an integral part of the process of regulating the nation’s environment and health.

Therefore, a better question might be: “Who exploits the issue of environmental protection for political gain?” That answer, it appears, unfolds today for American voters.

Brian C. Black

Professor of History and Environmental Studies, Pennsylvania State University

Pennsylvania State University provides funding as a founding partner of

Professor of History and Environmental Studies, Pennsylvania State University

Pennsylvania State University provides funding as a founding partner of

The Conversation