COVID cluckers: Pandemic feeds demand for backyard chickens

by Terence Chea

DECEMBER 30, 2020

Ron and Allison Abta hold hens in front of their backyard chicken run in Ross, Calif., Dec. 15, 2020. The coronavirus pandemic is coming home to roost in America's backyards. Forced to hunker down at home, more people are setting up coops and raising their own chickens, which provide an earthy hobby, animal companionship and a steady supply of fresh eggs. (AP Photo/Terry Chea)

The coronavirus pandemic is coming home to roost in America's backyards.

Forced to hunker down at home, more people are setting up coops and raising their own chickens, which provide an earthy hobby, animal companionship and a steady supply of fresh eggs.

Amateur chicken-keeping has been growing in popularity in recent years as people seek environmental sustainability in the food they eat. The pandemic is accelerating those trends, some breeders and poultry groups say, prompting more people to make the leap into poultry parenthood.

Businesses that sell chicks, coops and other supplies say they have seen a surge in demand since the pandemic took hold in March and health officials ordered residents to stay home.

Allison and Ron Abta of Northern California's Marin County had for years talked about setting up a backyard coop. They took the plunge in August.

The couple's three kids were thrilled when their parents finally agreed to buy chicks.

"These chickens are like my favorite thing, honestly," said 12-year-old Violet, holding a dark feathered hen in her woodsy backyard. "They actually have personalities once you get to know them."

The coronavirus pandemic is coming home to roost in America's backyards.

Forced to hunker down at home, more people are setting up coops and raising their own chickens, which provide an earthy hobby, animal companionship and a steady supply of fresh eggs.

Amateur chicken-keeping has been growing in popularity in recent years as people seek environmental sustainability in the food they eat. The pandemic is accelerating those trends, some breeders and poultry groups say, prompting more people to make the leap into poultry parenthood.

Businesses that sell chicks, coops and other supplies say they have seen a surge in demand since the pandemic took hold in March and health officials ordered residents to stay home.

Allison and Ron Abta of Northern California's Marin County had for years talked about setting up a backyard coop. They took the plunge in August.

The couple's three kids were thrilled when their parents finally agreed to buy chicks.

"These chickens are like my favorite thing, honestly," said 12-year-old Violet, holding a dark feathered hen in her woodsy backyard. "They actually have personalities once you get to know them."

Members of the Abta family, from left, Allison, Violet, Eli, and Ariella hold hens in front of their backyard chicken run in Ross, Calif., on Dec. 15, 2020. The coronavirus pandemic is coming home to roost in America's backyards. Forced to hunker down at home, more people are setting up coops and raising their own chickens, which provide an earthy hobby, animal companionship and a steady supply of fresh eggs. (AP Photo/Terry Chea)

The baby birds lived inside the family's home for six weeks before moving into the chicken run in the yard. A wire-mesh enclosure now houses the five heritage hens—each a different breed—and protects them from bobcats, foxes and other predators.

Mark Podgwaite, a Vermont chicken breeder who heads the American Poultry Association, said he and other breeders have noticed an uptick in demand for chicks since the pandemic began. His organization, which represents breeders and poultry-show exhibitors, has seen a jump in new members.

"Without question, the resurgence in raising backyard poultry has been unbelievable over the past year," said Podgwaite, who keeps a flock of roughly 100 birds. "It just exploded. Whether folks wanted birds just for eggs or eggs and meat, it seemed to really, really take off."

The Abta family bought the chicks from Mill Valley Chickens, which sells chickens, feed and supplies and builds coops and runs. Owner Leslie Citroen also offers classes for first-time chicken keepers. She estimates her sales have grown 400% this year.

"Once COVID hit, my phone just started ringing off the hook and it just has not slowed down," Citroen said. "I don't think it's going to slow down. I think this new interest and passion in chickens is permanent."

Citroen said most of her customers this year are first-time chicken keepers. They range from parents looking for something to keep homebound children busy to "preppers" who want their own protein supply in case the world falls apart.

"Demand is just through the roof right now," Citroen said. "I've sold all my baby chicks. I've sold all my juveniles. And I'm starting to sell some of my family flock."

One of her newest customers is Ben Duddleston, who lives in nearby San Anselmo. He stopped by her home to buy three hens.

The self-described "first-time chicken dad" wanted to surprise his kids, ages 5 and 10, on Christmas.

"I think it's totally pandemic related. I don't think that I'd be doing this if in normal times," Duddleston said.

Explore further National warning on backyard chooks after salmonella outbreaks

© 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.

The baby birds lived inside the family's home for six weeks before moving into the chicken run in the yard. A wire-mesh enclosure now houses the five heritage hens—each a different breed—and protects them from bobcats, foxes and other predators.

Mark Podgwaite, a Vermont chicken breeder who heads the American Poultry Association, said he and other breeders have noticed an uptick in demand for chicks since the pandemic began. His organization, which represents breeders and poultry-show exhibitors, has seen a jump in new members.

"Without question, the resurgence in raising backyard poultry has been unbelievable over the past year," said Podgwaite, who keeps a flock of roughly 100 birds. "It just exploded. Whether folks wanted birds just for eggs or eggs and meat, it seemed to really, really take off."

The Abta family bought the chicks from Mill Valley Chickens, which sells chickens, feed and supplies and builds coops and runs. Owner Leslie Citroen also offers classes for first-time chicken keepers. She estimates her sales have grown 400% this year.

Ben Duddleston discusses buying chickens and supplies from Leslie Citroen, owner of Mill Valley Chickens in Mill Valley, Calif., Dec. 15, 2020. The coronavirus pandemic is coming home to roost in America's backyards. Citroen says demand for heritage hens has increased sharply since the pandemic began and Duddleston says the pandemic influenced his decision to become a "first-time chicken dad." (AP Photo/Terry Chea)

A heritage hen sits on a wire enclosure at Mill Valley Chickens in Mill Valley, Calif., Dec. 15, 2020. The coronavirus pandemic is coming home to roost in America's backyards. Owner Leslie Citroen says demand for backyard chickens has increased sharply since the pandemic began. (AP Photo/Terry Chea)

"Once COVID hit, my phone just started ringing off the hook and it just has not slowed down," Citroen said. "I don't think it's going to slow down. I think this new interest and passion in chickens is permanent."

Citroen said most of her customers this year are first-time chicken keepers. They range from parents looking for something to keep homebound children busy to "preppers" who want their own protein supply in case the world falls apart.

"Demand is just through the roof right now," Citroen said. "I've sold all my baby chicks. I've sold all my juveniles. And I'm starting to sell some of my family flock."

One of her newest customers is Ben Duddleston, who lives in nearby San Anselmo. He stopped by her home to buy three hens.

The self-described "first-time chicken dad" wanted to surprise his kids, ages 5 and 10, on Christmas.

"I think it's totally pandemic related. I don't think that I'd be doing this if in normal times," Duddleston said.

Explore further National warning on backyard chooks after salmonella outbreaks

© 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.

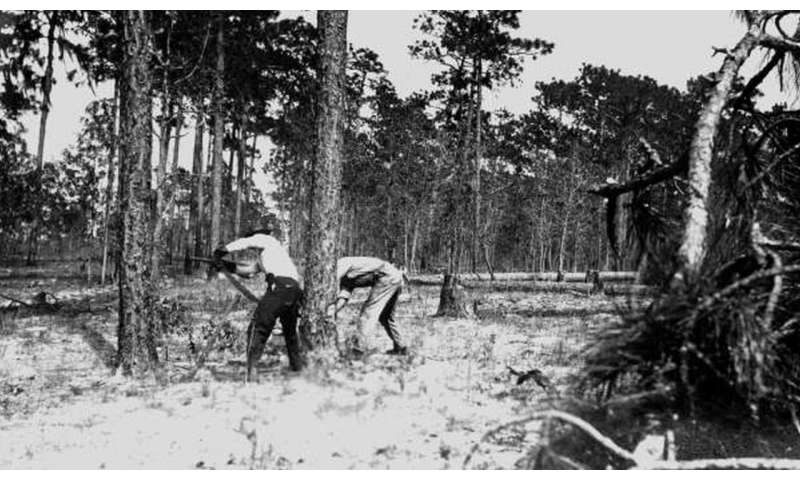

A stand of 80- to 85-year-old longleaf pines and an open, grassy area where seedlings can grow unhampered—including a few at the top of the shadow are seen in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss. Landowners and government agencies in nine states from Texas to Virginia are working to bring back longleaf pines, planting seedlings in some areas and managing others to remove shrubs and other kinds of trees. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)

A stand of 80- to 85-year-old longleaf pines and an open, grassy area where seedlings can grow unhampered—including a few at the top of the shadow are seen in the DeSoto National Forest in Miss. Landowners and government agencies in nine states from Texas to Virginia are working to bring back longleaf pines, planting seedlings in some areas and managing others to remove shrubs and other kinds of trees. (AP Photo/Janet McConnaughey)