A special report on the first anniversary of the mission launched on July 20, 2020

Published: July 19, 2021 1

Dubai: July 20 — in the early hours of this day last year, the UAE’s dream of reaching for the stars was realised. Hope Probe, the first Arab interplanetary mission, was successfully launched from Tanegashima Space Centre (TNSC) in the Kagoshima Prefecture of southwestern Japan at 1.58am (UAE time) on July 20, 2020.

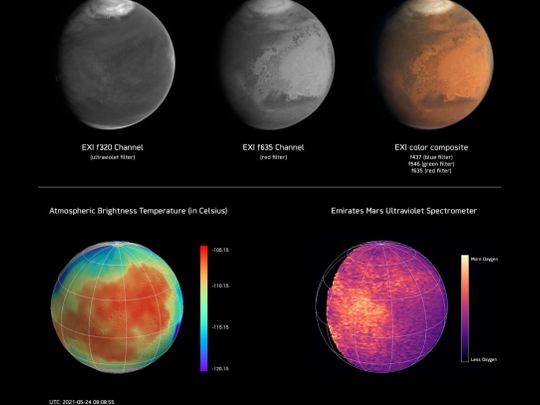

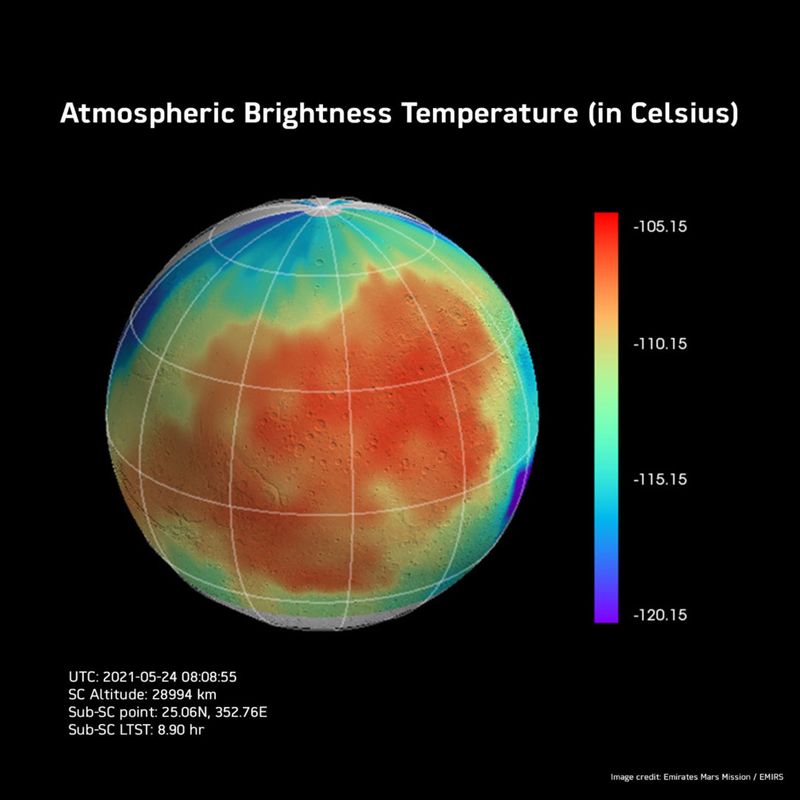

One year has passed and Hope Probe is currently orbiting the Red Planet to create a complete picture of the Martian atmosphere. “The mission has not only performed nominally across all areas, but has exceeded its anticipated performance, encompassing a range of additional activities and freeing up valuable resources to perform additional observations,” said the Emirates Mars Mission (EMM) on the eve of its first anniversary.

‘From strength to strength’

Omran Sharaf

EMM project director Omran Sharaf said on Monday: “We’ve had quite a lot of ‘wiggle room’ in addition to our planned parameters and our confidence in our spacecraft has gone from strength to strength, to be honest. We were able to cut the number of trajectory correction manoeuvres, perform additional observations during our flight to Mars and now have added a whole area of scientific study to the mission that I can only describe as a ‘bonus’. It has been a very busy year indeed for Hope Probe.”

‘A day full of pride’

Recalling the historic moment, Sharaf said in an earlier interview with Gulf News: “It was a day “full of pride, happiness and positivity. Yes, it was a very busy, intense and stressful day; but personally, I was confident about the teamwork and spacecraft design.”

Hope Probe journeyed over 493 million km to reach the Red Planet. The original seven Trajectory Correction Manoeuvres (TCMs) was cut to four because of the spacecraft’s outstanding performance during the Launch and Early Operations Phase (LEOPs). This conserved resources and allowed the EMM team to perform a series of observations en route to Mars.

Then came the most critical part of the mission — the Mars Orbit Insertion (MOI). Worried, scared, but confident — it was definitely a mixed feeling for Sharaf and his team who have reached that point — the farthest that any Arab would go in the universe. They only had one shot and with only 50 per cent success rate — it could go either way: failure or accomplishment.

Entering Mars

On February 9, Hope Probe entered the Mars orbit. Sharaf told Gulf News: “After we arrived, the stress went away. The feeling was very difficult to describe. For the first few minutes, I was still in shock. The past seven years (from Hope Probe announcement in 2014), went really fast in front of me. It took me a while to realise our feat and it was a good feeling. Now, the load is still high but the stress level is significantly less.”

Members of the EMM then worked on calibrating Hope Probe’s scientific instruments to make sure the Martian atmospheric data that will be collected were accurate as they shifted to to Science orbit.

Cruise to Mars

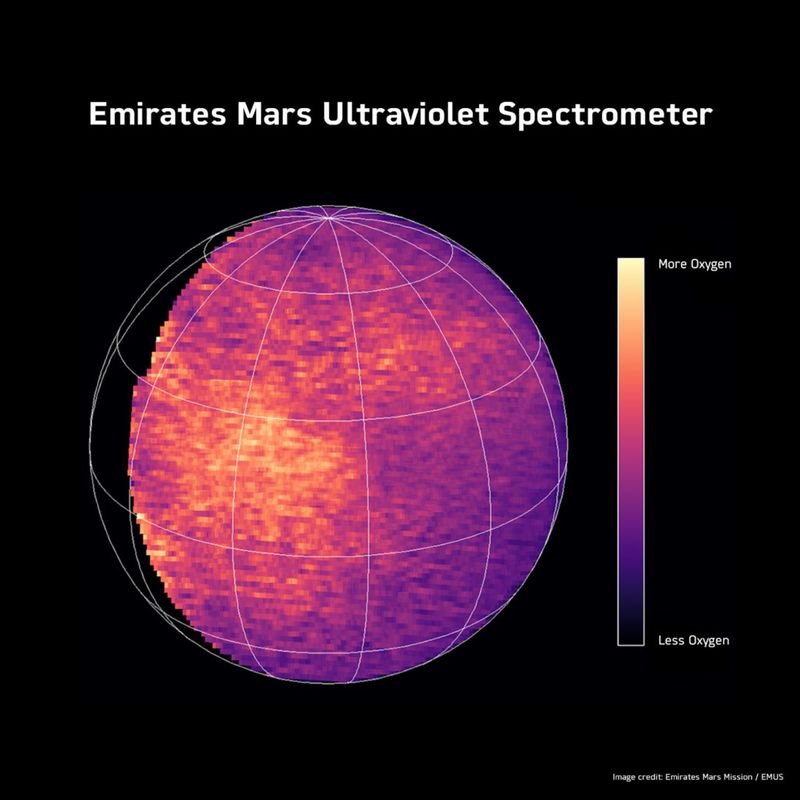

EMM’s Emirates Mars Ultraviolet Spectrometer (EMUS) instrument was activated during Hope’s cruise to Mars and used to image Mars’ exospheric hydrogen. The instrument was also cross-calibrated with the PHEBUS spectrometer aboard the European Space Agency’s BepiColombo spacecraft, itself en route to Mercury. “These experiments were possible simply because Mars Hope was in such good shape,” Hessa Al Matroushi, EMM’s Science Lead, recalled.

Because resources were available and the spacecraft performance so exceeded planning scenarios, the dust tracking feature of Mars Hope’s star tracker instruments was also enabled, allowing measurements of interplanetary dust in the wake of Mars as it spins around the sun.

WHY STUDY MARS

EMM has repeatedly answered the question — why study the Red Planet. It replied: “Mars has captured human imagination for centuries. Now, we are at a junction where we know a great deal about the planet, and we have the vision and technology to explore further. Mars is an obvious target for exploration for many reasons. From our pursuit to find extraterrestrial life to someday expand human civilisation to other planets, Mars serves as a long-term and collaborative project for the entire human race.”

As the first weather satellite of Mars, Hope (Al Amal in Arabic) is the first probe to provide a complete picture of the Martian atmosphere. It will help answer key questions about the global Martian atmosphere and the loss of hydrogen and oxygen gases into space over the span of one Martian year.

Specifically, Hope Probe will help humans “understand climate dynamics and the global weather map through characterising the lower atmosphere of Mars; explain how the weather changes the escape of hydrogen and oxygen through correlating the lower atmosphere conditions with the upper atmosphere; and understand the structure and variability of hydrogen and oxygen in the upper atmosphere, as well as identifying why Mars is losing them into space.”

Hope Probe transitioned to its unique 20,000-43,000km elliptical science orbit, with an inclination to Mars of 25 degrees. In this orbit, the is orbiting of the Red Planet every 55 hours to capture a full planetary sample every four orbits or nine Martian days.

Hope probe’s three instruments were activated on April 10 then a period of commissioning and testing followed, before the mission’s Science phase formally commenced on May 23. It was during this period that the EMM science team first made the stunning observations of Mars’ discrete aurora that have electrified the global Mars science community, releasing the first global images of Mars discrete aurora in the far-ultraviolet, and providing new insights into the discrete aurora phenomenon in Mars’ nightside atmosphere.

The mages of a ghostly glow known as Mars’ Discrete Aurora taken by Hope Probe’s EMUS instrument were released by the Emirates Mars Mission (EMM) on June 30. His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai, also tweeted about the Martian phenomenon and said: “The UAE’s Hope Probe, first-ever Arab interplanetary mission, has captured the first global images of Mars’ Discrete Aurora. The high-quality images open up unprecedented potential for the global science community to investigate solar interactions with Mars.”

Revolutionary scientific implications

According to EMM, the images taken by Hope Probe “have revolutionary implications for our understanding of the interactions between solar radiation, Mars’ magnetic fields and the planetary atmosphere.”

Al Matroushi noted: “These unique global snapshots of the Discrete Aurora of Mars are the first time such detailed and clear observations have been made globally, as well as across previously unobservable wavelengths. The implications for our understanding of Mars’ atmospheric and magnetospheric science are tremendous and provide new support to the theory that solar storms are not necessary to drive Mars’ aurora.”

EMM Deputy Science Lead Justin Deighan added: “We have totally blown out ten years of study of Mars’ auroras with ten minutes of observations. The data we are capturing confirms the tremendous potential we now have of exploring Mars’ aurora and the interactions between Mars’ magnetic fields, atmosphere and solar particles with a coverage and sensitivity we could only previously dream of. These exciting observations go above and beyond the original science goals of Hope Probe.”

Sharing Science data with the world

Hope Probe has a two-year mission to map Mar’s atmospheric dynamics. According to EMM, the first Science data from the mission will be released globally with no embargo, following a period of validation and checking, on October 2021. “Hope Probe is the culmination of a knowledge transfer and development effort started in 2006, which has seen Emirati engineers working with partners around the world to develop the UAE’s spacecraft design, engineering and manufacturing capabilities,” EMM noted.

Beyond Mars

Hope Probe’s historic journey to the Red Planet coincides with a year of celebrations to mark the UAE’s Golden Jubilee. According to EMM, “beyond the scientific objectives of Hope Probe are its strategic objectives that revolve around human knowledge, Emirati capabilities, and global collaboration.”

The mission will achieve beyond data and results. It will improve the quality of life on Earth by pushing our limits to make new discoveries; encourage global collaboration in Mars exploration; demonstrate leadership in space research; build Emirati capabilities in the field of interplanetary exploration; boost scientific knowledge because a sustainable, future-proof economy is a knowledge-based economy; inspire future Arab generations to pursue space science; and establish the UAE’s position as a beacon of progress in the region.

Photos: Landmarks in red mark UAE Hope Probe

In photos: UAE Hope Probe launch as it happened

UAE Hope Probe in Mars orbit: Leaders laud success of mission - see photos

Photos: UAE leaders honour Hope Probe team

Pictures: Blast off to Mars for UAE's Hope Probe mission

Photos: UAE’s Hope Probe creates history

Look: Latest images of Mars taken by UAE’s Hope Probe

UAE Hope Probe shares images of Mars’ Discrete Aurora

Emirates Mars Mission receives prestigious Sir Arthur Clarke Award in London

Meet Omran Sharaf: The man behind UAE’s Hope Probe

UAE’s Hope Probe now on its science orbit around Mars

Mars Hope Probe: A quantum leap forward