Study finds high risk groups rejecting the COVID-19 vaccine in England

To increase COVID-19 vaccination rates, public health officials must understand who is refusing the vaccines. New research led by Ben Goldacre from the University of Oxford found that about 2% of people considered high-risk did not want the vaccine when offered. In addition, vaccination refusal in priority groups was most common among English people who are Black, South Asian, or from lower socioeconomic areas.

COVID-19 vaccines were offered to all patients in England within vaccine priority groups by mid-April 2021.

There is a concern of vaccine refusal from people labeled high-risk of contracting severe COVID-19 infection and who have a higher risk of dying from the disease. Also, the spreading of the coronavirus may heighten the chances of the virus festering and mutating in the body of an immunocompromised person — increasing the risk for a potentially new and dangerous variant.

The study “Recording of COVID-19 vaccine declined” among vaccination priority groups: a cohort study on 57.9 million NHS patients’ primary care records in situ using OpenSAFELY” is published on the medRxiv* preprint server.

.jpg)

Study details

The researchers collected medical records from 57.9 million patients to identify patients in vaccine priority groups who refused the vaccine.

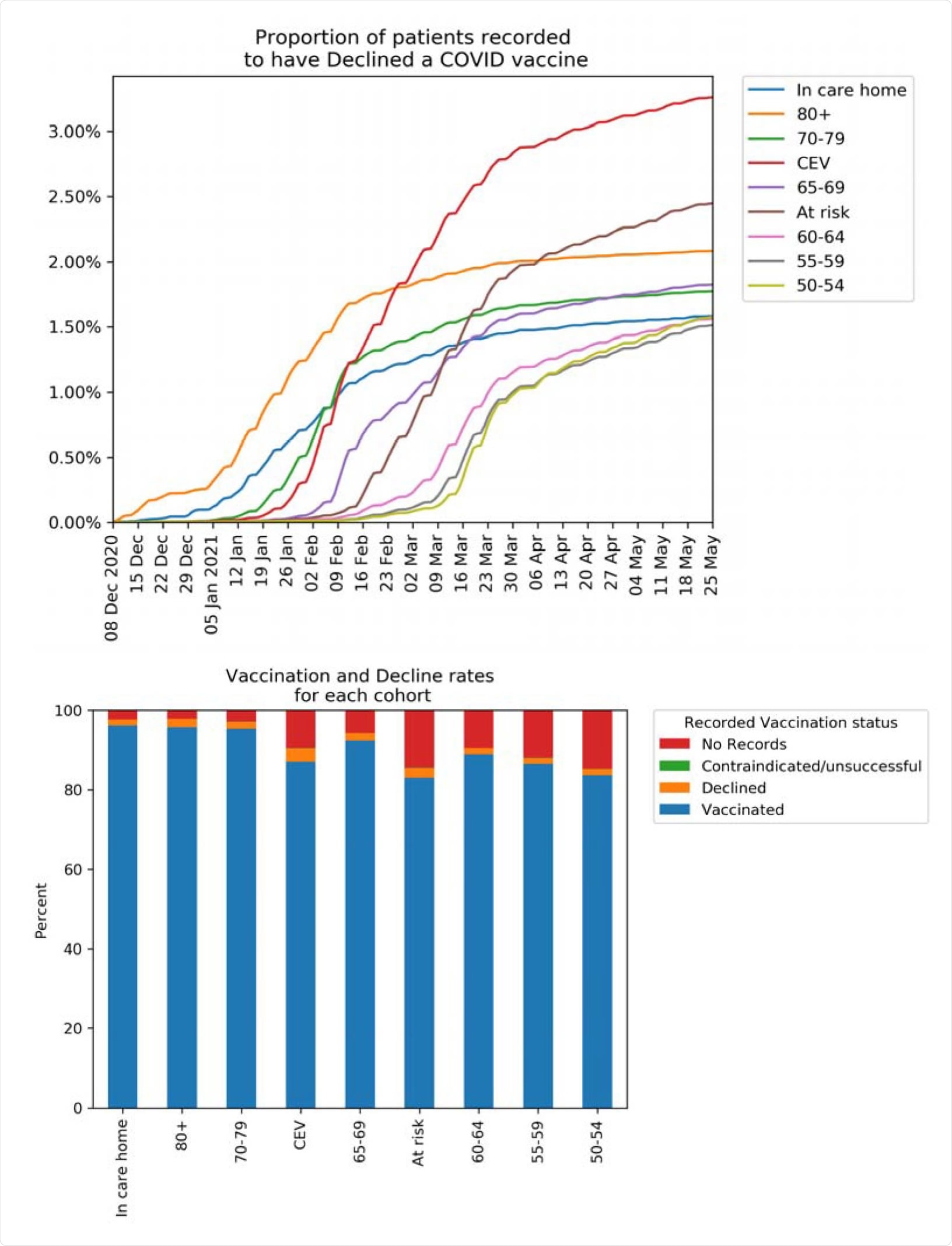

As of May 25, 2021, there were 24.5 million patients who were considered vaccine priority groups. Of these, 89.2% reported getting a COVID-19 vaccine, and 8.8% did not report any information on vaccination status.

People considered clinically extremely vulnerable (4.4%) were among the highest to have a vaccine refusal on record. This was followed by people over 80 (3.4%) and people considered at risk (3%).

Black people over the age of 80 were more likely to refuse a vaccine (15.3%) compared to South Asians (5.6%) and White people (1.5%).

Some factors may have contributed to vaccine refusal. For example, the research team found that people with severe mental health conditions or a learning disability had low vaccination rates. People were also more likely to refuse a vaccine if they were pregnant compared to nonpregnant people at childbearing age.

About 18% of people who initially refused

the vaccine changed their minds

About 2.7% stated that they declined the vaccine when it was offered to them. However, of the 2.7% who refused, 18.9% of these patients were later vaccinated.

Of the 18.9% who later became vaccinated, 13.1% were from the ‘At-Risk’ group and 30.7% in people over 80.

The research team also noted that people who were later vaccinated might have changed their minds as more time passed and coronavirus information became more available.

Clinical coding of vaccine refusal across

medical practices

Almost all medical practices in England have clinical codes to record whether someone has refused a vaccine. Results showed that almost every practice had at least one patient who refused the vaccine.

However, the team also found that the use of clinical codes varied across practices. Therefore, they suggest developing specific administrative codes specific to the COVID-19 vaccination campaign to help with recording patient data and for future booster shots.

*Important Notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Curtis HJ, et al. Recording of “COVID-19 vaccine declined” among vaccination priority groups: a cohort study on 57.9 million NHS patients’ primary care records in situ using OpenSAFELY. medRxiv, 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.05.21259863, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.05.21259863v1

Posted in: Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News