The year 2020 exposed the risks and weaknesses of the market-driven global system like never before. It’s hard to avoid the sense that a turning point has been reached

Composite: Guardian Design/AFP/Getty/Shutterstock/Xinhua/EPA/Reuters

The long read

by Adam Tooze

Thu 2 Sep 2021

If one word could sum up the experience of 2020, it would be disbelief. Between Xi Jinping’s public acknowledgment of the coronavirus outbreak on 20 January 2020, and Joe Biden’s inauguration as the 46th president of the United States precisely a year later, the world was shaken by a disease that in the space of 12 months killed more than 2.2 million people and rendered tens of millions severely ill. Today the official death tolls stands at 4.51 million. The likely figure for excess deaths is more than twice that number. The virus disrupted the daily routine of virtually everyone on the planet, stopped much of public life, closed schools, separated families, interrupted travel and upended the world economy.

To contain the fallout, government support for households, businesses and markets took on dimensions not seen outside wartime. It was not just by far the sharpest economic recession experienced since the second world war, it was qualitatively unique. Never before had there been a collective decision, however haphazard and uneven, to shut large parts of the world’s economy down. It was, as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) put it, “a crisis like no other”.

Even before we knew what would hit us, there was every reason to think that 2020 might be tumultuous. The conflict between China and the US was boiling up. A “new cold war” was in the air. Global growth had slowed seriously in 2019. The IMF worried about the destabilising effect that geopolitical tension might have on a world economy that was already piled high with debt. Economists cooked up new statistical indicators to track the uncertainty that was dogging investment. The data strongly suggested that the source of the trouble was in the White House. The US’s 45th president, Donald Trump, had succeeded in turning himself into an unhealthy global obsession. He was up for reelection in November and seemed bent on discrediting the electoral process even if it yielded a win. Not for nothing, the slogan of the 2020 edition of the Munich Security Conference – the Davos for national security types – was “Westlessness”.

Get the Guardian’s award-winning long reads sent direct to you every Saturday morning

Apart from the worries about Washington, the clock on the Brexit negotiations was running out. Even more alarming for Europe as 2020 began was the prospect of a new refugee crisis. In the background lurked both the threat of a final grisly escalation in Syria’s civil war and the chronic problem of underdevelopment. The only way to remedy that was to energise investment and growth in the global south. The flow of capital, however, was unstable and unequal. At the end of 2019, half the lowest-income borrowers in sub-Saharan Africa were already approaching the point at which they could no longer service their debts.

The pervasive sense of risk and anxiety that hung around the world economy was a remarkable reversal. Not so long before, the west’s apparent triumph in the cold war, the rise of market finance, the miracles of information technology, and the widening orbit of economic growth appeared to cement the capitalist economy as the all-conquering driver of modern history. In the 1990s, the answer to most political questions had seemed simple: “It’s the economy, stupid.” As economic growth transformed the lives of billions, there was, Margaret Thatcher liked to say, “no alternative”. That is, there was no alternative to an order based on privatisation, light-touch regulation and the freedom of movement of capital and goods. As recently as 2005, Britain’s centrist prime minister Tony Blair could declare that to argue about globalisation made as much sense as arguing about whether autumn should follow summer.

By 2020, globalisation and the seasons were very much in question. The economy had morphed from being the answer to being the question. A series of deep crises – beginning in Asia in the late 90s and moving to the Atlantic financial system in 2008, the eurozone in 2010 and global commodity producers in 2014 – had shaken confidence in market economics. All those crises had been overcome, but by government spending and central bank interventions that drove a coach and horses through firmly held precepts about “small government” and “independent” central banks. The crises had been brought on by speculation, and the scale of the interventions necessary to stabilise them had been historic. Yet the wealth of the global elite continued to expand. Whereas profits were private, losses were socialised. Who could be surprised, many now asked, if surging inequality led to populist disruption? Meanwhile, with China’s spectacular ascent, it was no longer clear that the great gods of growth were on the side of the west.

Advertisement

And then, in January 2020, the news broke from Beijing. China was facing a full-blown epidemic of a novel coronavirus. This was the natural “blowback” that environmental campaigners had long warned us about, but whereas the climate crisis caused us to stretch our minds to a planetary scale and set a timetable in terms of decades, the virus was microscopic and all-pervasive, and was moving at a pace of days and weeks. It affected not glaciers and ocean tides, but our bodies. It was carried on our breath. It would put not just individual national economies but the world’s economy in question.

As it emerged from the shadows, Sars-CoV-2 had the look about it of a catastrophe foretold. It was precisely the kind of highly contagious, flu-like infection that virologists had predicted. It came from one of the places they expected it to come from – the region of dense interaction between wildlife, agriculture and urban populations sprawled across east Asia. It spread, predictably, through the channels of global transport and communication. It had, frankly, been a while coming.

There have been far more lethal pandemics. What was dramatically new about coronavirus in 2020 was the scale of the response. It was not just rich countries that spent enormous sums to support citizens and businesses – poor and middle-income countries were willing to pay a huge price, too. By early April, the vast majority of the world outside China, where it had already been contained, was involved in an unprecedented effort to stop the virus. “This is the real first world war,” said Lenín Moreno, president of Ecuador, one of the hardest-hit countries. “The other world wars were localised in [some] continents with very little participation from other continents … but this affects everyone. It is not localised. It is not a war from which you can escape.”

Lockdown is the phrase that has come into common use to describe our collective reaction. The very word is contentious. Lockdown suggests compulsion. Before 2020, it was a term associated with collective punishment in prisons. There were moments and places where that is a fitting description for the response to Covid. In Delhi, Durban and Paris, armed police patrolled the streets, took names and numbers, and punished those who violated curfews. In the Dominican Republic, an astonishing 85,000 people, almost 1% of the population, were arrested for violating the lockdown.

Even if no violence was involved, a government-mandated closure of all eateries and bars could feel repressive to their owners and clients. But lockdown seems a one-sided way of describing the economic reaction to the coronavirus. Mobility fell precipitately, well before government orders were issued. The flight to safety in financial markets began in late February. There was no jailer slamming the door and turning the key; rather, investors were running for cover. Consumers were staying at home. Businesses were closing or shifting to home working. By mid-March, shutting down became the norm. Those who were outside national territorial space, like hundreds of thousands of seafarers, found themselves banished to a floating limbo.

Thu 2 Sep 2021

If one word could sum up the experience of 2020, it would be disbelief. Between Xi Jinping’s public acknowledgment of the coronavirus outbreak on 20 January 2020, and Joe Biden’s inauguration as the 46th president of the United States precisely a year later, the world was shaken by a disease that in the space of 12 months killed more than 2.2 million people and rendered tens of millions severely ill. Today the official death tolls stands at 4.51 million. The likely figure for excess deaths is more than twice that number. The virus disrupted the daily routine of virtually everyone on the planet, stopped much of public life, closed schools, separated families, interrupted travel and upended the world economy.

To contain the fallout, government support for households, businesses and markets took on dimensions not seen outside wartime. It was not just by far the sharpest economic recession experienced since the second world war, it was qualitatively unique. Never before had there been a collective decision, however haphazard and uneven, to shut large parts of the world’s economy down. It was, as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) put it, “a crisis like no other”.

Even before we knew what would hit us, there was every reason to think that 2020 might be tumultuous. The conflict between China and the US was boiling up. A “new cold war” was in the air. Global growth had slowed seriously in 2019. The IMF worried about the destabilising effect that geopolitical tension might have on a world economy that was already piled high with debt. Economists cooked up new statistical indicators to track the uncertainty that was dogging investment. The data strongly suggested that the source of the trouble was in the White House. The US’s 45th president, Donald Trump, had succeeded in turning himself into an unhealthy global obsession. He was up for reelection in November and seemed bent on discrediting the electoral process even if it yielded a win. Not for nothing, the slogan of the 2020 edition of the Munich Security Conference – the Davos for national security types – was “Westlessness”.

Get the Guardian’s award-winning long reads sent direct to you every Saturday morning

Apart from the worries about Washington, the clock on the Brexit negotiations was running out. Even more alarming for Europe as 2020 began was the prospect of a new refugee crisis. In the background lurked both the threat of a final grisly escalation in Syria’s civil war and the chronic problem of underdevelopment. The only way to remedy that was to energise investment and growth in the global south. The flow of capital, however, was unstable and unequal. At the end of 2019, half the lowest-income borrowers in sub-Saharan Africa were already approaching the point at which they could no longer service their debts.

The pervasive sense of risk and anxiety that hung around the world economy was a remarkable reversal. Not so long before, the west’s apparent triumph in the cold war, the rise of market finance, the miracles of information technology, and the widening orbit of economic growth appeared to cement the capitalist economy as the all-conquering driver of modern history. In the 1990s, the answer to most political questions had seemed simple: “It’s the economy, stupid.” As economic growth transformed the lives of billions, there was, Margaret Thatcher liked to say, “no alternative”. That is, there was no alternative to an order based on privatisation, light-touch regulation and the freedom of movement of capital and goods. As recently as 2005, Britain’s centrist prime minister Tony Blair could declare that to argue about globalisation made as much sense as arguing about whether autumn should follow summer.

By 2020, globalisation and the seasons were very much in question. The economy had morphed from being the answer to being the question. A series of deep crises – beginning in Asia in the late 90s and moving to the Atlantic financial system in 2008, the eurozone in 2010 and global commodity producers in 2014 – had shaken confidence in market economics. All those crises had been overcome, but by government spending and central bank interventions that drove a coach and horses through firmly held precepts about “small government” and “independent” central banks. The crises had been brought on by speculation, and the scale of the interventions necessary to stabilise them had been historic. Yet the wealth of the global elite continued to expand. Whereas profits were private, losses were socialised. Who could be surprised, many now asked, if surging inequality led to populist disruption? Meanwhile, with China’s spectacular ascent, it was no longer clear that the great gods of growth were on the side of the west.

Advertisement

And then, in January 2020, the news broke from Beijing. China was facing a full-blown epidemic of a novel coronavirus. This was the natural “blowback” that environmental campaigners had long warned us about, but whereas the climate crisis caused us to stretch our minds to a planetary scale and set a timetable in terms of decades, the virus was microscopic and all-pervasive, and was moving at a pace of days and weeks. It affected not glaciers and ocean tides, but our bodies. It was carried on our breath. It would put not just individual national economies but the world’s economy in question.

As it emerged from the shadows, Sars-CoV-2 had the look about it of a catastrophe foretold. It was precisely the kind of highly contagious, flu-like infection that virologists had predicted. It came from one of the places they expected it to come from – the region of dense interaction between wildlife, agriculture and urban populations sprawled across east Asia. It spread, predictably, through the channels of global transport and communication. It had, frankly, been a while coming.

There have been far more lethal pandemics. What was dramatically new about coronavirus in 2020 was the scale of the response. It was not just rich countries that spent enormous sums to support citizens and businesses – poor and middle-income countries were willing to pay a huge price, too. By early April, the vast majority of the world outside China, where it had already been contained, was involved in an unprecedented effort to stop the virus. “This is the real first world war,” said Lenín Moreno, president of Ecuador, one of the hardest-hit countries. “The other world wars were localised in [some] continents with very little participation from other continents … but this affects everyone. It is not localised. It is not a war from which you can escape.”

Lockdown is the phrase that has come into common use to describe our collective reaction. The very word is contentious. Lockdown suggests compulsion. Before 2020, it was a term associated with collective punishment in prisons. There were moments and places where that is a fitting description for the response to Covid. In Delhi, Durban and Paris, armed police patrolled the streets, took names and numbers, and punished those who violated curfews. In the Dominican Republic, an astonishing 85,000 people, almost 1% of the population, were arrested for violating the lockdown.

Even if no violence was involved, a government-mandated closure of all eateries and bars could feel repressive to their owners and clients. But lockdown seems a one-sided way of describing the economic reaction to the coronavirus. Mobility fell precipitately, well before government orders were issued. The flight to safety in financial markets began in late February. There was no jailer slamming the door and turning the key; rather, investors were running for cover. Consumers were staying at home. Businesses were closing or shifting to home working. By mid-March, shutting down became the norm. Those who were outside national territorial space, like hundreds of thousands of seafarers, found themselves banished to a floating limbo.

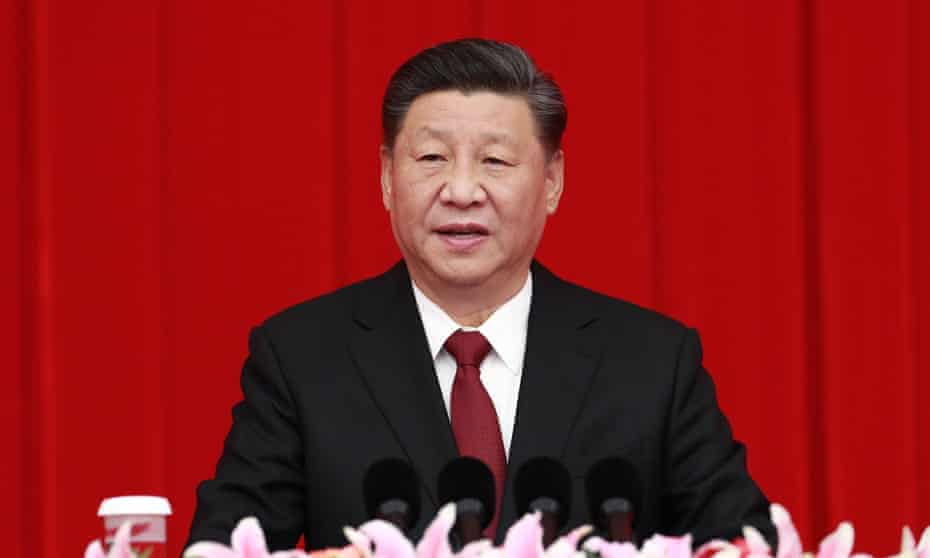

President Xi Jinping in January 2020.

Photograph: Nareshkumar Shaganti/Alamy

The widespread adoption of the term “lockdown” is an index of how contentious the politics of the virus would turn out to be. Societies, communities and families quarrelled bitterly over face masks, social distancing and quarantine. The entire experience was an example on the grandest scale of what the German sociologist Ulrich Beck in the 80s dubbed “risk society”. As a result of the development of modern society, we found ourselves collectively haunted by an unseen threat, visible only to science, a risk that remained abstract and immaterial until you fell sick, and the unlucky ones found themselves slowly drowning in the fluid accumulating in their lungs.

One way to react to such a situation of risk is to retreat into denial. That may work. It would be naive to imagine otherwise. Many pervasive diseases and social ills, including many that cause loss of life on a large scale, are ignored and naturalised, treated as “facts of life”. With regard to the largest environmental risks, notably the climate crisis, one might say that our normal mode of operation is denial and willful ignorance on a grand scale.

Facing up to the pandemic was what the vast majority of people all over the world tried to do. But the problem, as Beck said, is that getting to grips with the really large-scale, all-pervasive risks that modern society generates is easier said than done. It requires agreement on what the risk is. It also requires critical engagement with our own behaviour, and with the social order to which it belongs. It requires a willingness to make political choices about resource distribution and priorities at every level. Such choices clash with the prevalent desire of the last 40 years to depoliticise, to use markets or the law to avoid such decisions. This is the basic thrust behind neoliberalism, or the market revolution – to depoliticise distributional issues, including the very unequal consequences of societal risks, whether those be due to structural change in the global division of labour, environmental damage, or disease.

Coronavirus glaringly exposed our institutional lack of preparation, what Beck called our “organised irresponsibility”. It revealed the weakness of basic apparatuses of state administration, like up-to-date government databases. To face the crisis, we needed a society that gave far greater priority to care. Loud calls issued from unlikely places for a “new social contract” that would properly value essential workers and take account of the risks generated by the globalised lifestyles enjoyed by the most fortunate.

It fell to governments mainly of the centre and the right to meet the crisis. Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Donald Trump in the US experimented with denial. In Mexico, the notionally leftwing government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador also pursued a maverick path, refusing to take drastic action. Nationalist strongmen such as Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Narendra Modi in India, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey did not deny the virus, but relied on their patriotic appeal and bullying tactics to see them through.

It was the managerial centrist types who were under most pressure. Figures like Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer in the US, or Sebastián Piñera in Chile, Cyril Ramaphosa in South Africa, Emmanuel Macron, Angela Merkel, Ursula von der Leyen and their ilk in Europe. They accepted the science. Denial was not an option. They were desperate to demonstrate that they were better than the “populists”.

To meet the crisis, very middle-of-the-road politicians ended up doing very radical things. Most of it was improvisation and compromise, but insofar as they managed to put a programmatic gloss on their responses – whether in the form of the EU’s Next Generation programme or Biden’s Build Back Better programme in 2020 – it came from the repertoire of green modernisation, sustainable development and the Green New Deal.

The widespread adoption of the term “lockdown” is an index of how contentious the politics of the virus would turn out to be. Societies, communities and families quarrelled bitterly over face masks, social distancing and quarantine. The entire experience was an example on the grandest scale of what the German sociologist Ulrich Beck in the 80s dubbed “risk society”. As a result of the development of modern society, we found ourselves collectively haunted by an unseen threat, visible only to science, a risk that remained abstract and immaterial until you fell sick, and the unlucky ones found themselves slowly drowning in the fluid accumulating in their lungs.

One way to react to such a situation of risk is to retreat into denial. That may work. It would be naive to imagine otherwise. Many pervasive diseases and social ills, including many that cause loss of life on a large scale, are ignored and naturalised, treated as “facts of life”. With regard to the largest environmental risks, notably the climate crisis, one might say that our normal mode of operation is denial and willful ignorance on a grand scale.

Facing up to the pandemic was what the vast majority of people all over the world tried to do. But the problem, as Beck said, is that getting to grips with the really large-scale, all-pervasive risks that modern society generates is easier said than done. It requires agreement on what the risk is. It also requires critical engagement with our own behaviour, and with the social order to which it belongs. It requires a willingness to make political choices about resource distribution and priorities at every level. Such choices clash with the prevalent desire of the last 40 years to depoliticise, to use markets or the law to avoid such decisions. This is the basic thrust behind neoliberalism, or the market revolution – to depoliticise distributional issues, including the very unequal consequences of societal risks, whether those be due to structural change in the global division of labour, environmental damage, or disease.

Coronavirus glaringly exposed our institutional lack of preparation, what Beck called our “organised irresponsibility”. It revealed the weakness of basic apparatuses of state administration, like up-to-date government databases. To face the crisis, we needed a society that gave far greater priority to care. Loud calls issued from unlikely places for a “new social contract” that would properly value essential workers and take account of the risks generated by the globalised lifestyles enjoyed by the most fortunate.

It fell to governments mainly of the centre and the right to meet the crisis. Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Donald Trump in the US experimented with denial. In Mexico, the notionally leftwing government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador also pursued a maverick path, refusing to take drastic action. Nationalist strongmen such as Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Narendra Modi in India, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey did not deny the virus, but relied on their patriotic appeal and bullying tactics to see them through.

It was the managerial centrist types who were under most pressure. Figures like Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer in the US, or Sebastián Piñera in Chile, Cyril Ramaphosa in South Africa, Emmanuel Macron, Angela Merkel, Ursula von der Leyen and their ilk in Europe. They accepted the science. Denial was not an option. They were desperate to demonstrate that they were better than the “populists”.

To meet the crisis, very middle-of-the-road politicians ended up doing very radical things. Most of it was improvisation and compromise, but insofar as they managed to put a programmatic gloss on their responses – whether in the form of the EU’s Next Generation programme or Biden’s Build Back Better programme in 2020 – it came from the repertoire of green modernisation, sustainable development and the Green New Deal.

German chancellor Angela Merkel with South Africa’s president Cyril Ramaphosa in Pretoria in early 2020.

Photograph: Dpa Picture Alliance/Alamy

The result was a bitter historic irony. Even as the advocates of the Green New Deal, such as Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, had gone down to political defeat, 2020 resoundingly confirmed the realism of their diagnosis. It was the Green New Deal that had squarely addressed the urgency of environmental challenges and linked it to questions of extreme social inequality. It was the Green New Deal that had insisted that in meeting these challenges, democracies could not allow themselves to be hamstrung by conservative economic doctrines inherited from the bygone battles of the 70s and discredited by the financial crisis of 2008. It was the Green New Deal that had mobilised engaged young citizens on whom democracy, if it was to have a hopeful future, clearly depended.

The Green New Deal had also, of course, demanded that rather than endlessly patching a system that produced and reproduced inequality, instability and crisis, it should be radically reformed. That was challenging for centrists. But one of the attractions of a crisis was that questions of the long-term future could be set aside. The year 2020 was all about survival.

The immediate economic policy response to the coronavirus shock drew directly on the lessons of 2008. Government spending and tax cuts to support the economy were even more prompt. Central bank interventions were even more spectacular. These fiscal and monetary policies together confirmed the essential insights of economic doctrines once advocated by radical Keynesians and made newly fashionable by doctrines such as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). State finances are not limited like those of a household. If a monetary sovereign treats the question of how to organise financing as anything more than a technical matter, that is itself a political choice. As John Maynard Keynes once reminded his readers in the midst of the second world war: “Anything we can actually do we can afford.” The real challenge, the truly political question, was to agree what we wanted to do and to figure out how to do it.

Experiments in economic policy in 2020 were not confined to the rich countries. Enabled by the abundance of dollars unleashed by the Fed, but drawing on decades of experience with fluctuating global capital flows, many emerging market governments, in Indonesia and Brazil for instance, displayed remarkable initiative in response to the crisis. They put to work a toolkit of policies that enabled them to hedge the risks of global financial integration. Ironically, unlike in 2008, China’s greater success in virus control left its economic policy looking relatively conservative. Countries such as Mexico and India, where the pandemic spread rapidly but governments failed to respond with large-scale economic policy, looked increasingly out of step with the times. The year would witness the head-turning spectacle of the IMF scolding a notionally leftwing Mexican government for failing to run a large enough budget deficit.

It was hard to avoid the sense that a turning point had been reached. Was this, finally, the death of the orthodoxy that had prevailed in economic policy since the 80s? Was this the death knell of neoliberalism? As a coherent ideology of government, perhaps. The idea that the natural envelope of economic activity – whether the disease environment or climate conditions – could be ignored or left to markets to regulate was clearly out of touch with reality. So, too, was the idea that markets could self-regulate in relation to all conceivable social and economic shocks. Even more urgently than in 2008, survival dictated interventions on a scale last seen in the second world war.

All this left doctrinaire economists gasping for breath. That in itself is not surprising. The orthodox understanding of economic policy was always unrealistic. In reality, neoliberalism had always been radically pragmatic. Its real history was that of a series of state interventions in the interests of capital accumulation, including the forceful deployment of state violence to bulldoze opposition. Whatever the doctrinal twists and turns, the social realities with which the market revolution had been entwined since the 1970s all endured until 2020. The historic force that finally burst the dykes of the neoliberal order was not radical populism or the revival of class struggle – it was a plague unleashed by heedless global growth and the massive flywheel of financial accumulation.

In 2008, the crisis had been brought on by the overexpansion of the banks and the excesses of mortgage securitisation. In 2020, the coronavirus hit the financial system from the outside, but the fragility that this shock exposed was internally generated. This time it was not banks that were the weak link, but the asset markets themselves. The shock went to the very heart of the system, the market for American Treasuries, the supposedly safe assets on which the entire pyramid of credit is based. If that had melted down, it would have taken the rest of the world with it.

The result was a bitter historic irony. Even as the advocates of the Green New Deal, such as Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, had gone down to political defeat, 2020 resoundingly confirmed the realism of their diagnosis. It was the Green New Deal that had squarely addressed the urgency of environmental challenges and linked it to questions of extreme social inequality. It was the Green New Deal that had insisted that in meeting these challenges, democracies could not allow themselves to be hamstrung by conservative economic doctrines inherited from the bygone battles of the 70s and discredited by the financial crisis of 2008. It was the Green New Deal that had mobilised engaged young citizens on whom democracy, if it was to have a hopeful future, clearly depended.

The Green New Deal had also, of course, demanded that rather than endlessly patching a system that produced and reproduced inequality, instability and crisis, it should be radically reformed. That was challenging for centrists. But one of the attractions of a crisis was that questions of the long-term future could be set aside. The year 2020 was all about survival.

The immediate economic policy response to the coronavirus shock drew directly on the lessons of 2008. Government spending and tax cuts to support the economy were even more prompt. Central bank interventions were even more spectacular. These fiscal and monetary policies together confirmed the essential insights of economic doctrines once advocated by radical Keynesians and made newly fashionable by doctrines such as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). State finances are not limited like those of a household. If a monetary sovereign treats the question of how to organise financing as anything more than a technical matter, that is itself a political choice. As John Maynard Keynes once reminded his readers in the midst of the second world war: “Anything we can actually do we can afford.” The real challenge, the truly political question, was to agree what we wanted to do and to figure out how to do it.

Experiments in economic policy in 2020 were not confined to the rich countries. Enabled by the abundance of dollars unleashed by the Fed, but drawing on decades of experience with fluctuating global capital flows, many emerging market governments, in Indonesia and Brazil for instance, displayed remarkable initiative in response to the crisis. They put to work a toolkit of policies that enabled them to hedge the risks of global financial integration. Ironically, unlike in 2008, China’s greater success in virus control left its economic policy looking relatively conservative. Countries such as Mexico and India, where the pandemic spread rapidly but governments failed to respond with large-scale economic policy, looked increasingly out of step with the times. The year would witness the head-turning spectacle of the IMF scolding a notionally leftwing Mexican government for failing to run a large enough budget deficit.

It was hard to avoid the sense that a turning point had been reached. Was this, finally, the death of the orthodoxy that had prevailed in economic policy since the 80s? Was this the death knell of neoliberalism? As a coherent ideology of government, perhaps. The idea that the natural envelope of economic activity – whether the disease environment or climate conditions – could be ignored or left to markets to regulate was clearly out of touch with reality. So, too, was the idea that markets could self-regulate in relation to all conceivable social and economic shocks. Even more urgently than in 2008, survival dictated interventions on a scale last seen in the second world war.

All this left doctrinaire economists gasping for breath. That in itself is not surprising. The orthodox understanding of economic policy was always unrealistic. In reality, neoliberalism had always been radically pragmatic. Its real history was that of a series of state interventions in the interests of capital accumulation, including the forceful deployment of state violence to bulldoze opposition. Whatever the doctrinal twists and turns, the social realities with which the market revolution had been entwined since the 1970s all endured until 2020. The historic force that finally burst the dykes of the neoliberal order was not radical populism or the revival of class struggle – it was a plague unleashed by heedless global growth and the massive flywheel of financial accumulation.

In 2008, the crisis had been brought on by the overexpansion of the banks and the excesses of mortgage securitisation. In 2020, the coronavirus hit the financial system from the outside, but the fragility that this shock exposed was internally generated. This time it was not banks that were the weak link, but the asset markets themselves. The shock went to the very heart of the system, the market for American Treasuries, the supposedly safe assets on which the entire pyramid of credit is based. If that had melted down, it would have taken the rest of the world with it.

A curfew sign in Miami, Florida, in March 2020.

Photograph: Eva Marie Uzcategui/AFP via Getty Images

The scale of stabilising interventions in 2020 was impressive. It confirmed the basic insistence of the Green New Deal that if the will was there, democratic states did have the tools they needed to exercise control over the economy. This was, however, a double-edged realisation, because if these interventions were an assertion of sovereign power, they were driven by crisis. As in 2008, they served the interests of those who had the most to lose. This time, not just individual banks but entire markets were declared too big to fail. To break that cycle of crisis and stabilising, and to make economic policy into a true exercise in democratic sovereignty, would require root-and-branch reform. That would require a real power shift, and the odds were stacked against that.

The massive economic policy interventions of 2020, like those of 2008, were Janus-faced. On the one hand, their scale exploded the bounds of neoliberal restraint and their economic logic confirmed the basic diagnosis of interventionist macroeconomics back to Keynes. When an economy was spiralling into recession, one did not have to accept the disaster as a natural cure, an invigorating purge. Instead, prompt and decisive government economic policy could prevent the collapse and forestall unnecessary unemployment, waste and social suffering.

These interventions could not but appear as harbingers of a new regime beyond neoliberalism. On the other hand, they were made from the top down. They were politically thinkable only because there was no challenge from the left and their urgency was impelled by the need to stabilise the financial system. And they delivered. Over the course of 2020, household net worth in the US increased by more than $15tn. Yet that overwhelmingly benefited the top 1%, who owned almost 40% of all stocks. The top 10%, between them, owned 84%. If this was indeed a “new social contract”, it was an alarmingly one-sided affair.

Nevertheless, 2020 was a moment not just of plunder, but of reformist experimentation. In response to the threat of social crisis, new modes of welfare provision were tried out in Europe, the US and many emerging market economies. And in search of a positive agenda, centrists embraced environmental policy and the issue of the climate crisis as never before. Contrary to the fear that Covid-19 would distract from other priorities, the political economy of the Green New Deal went mainstream. “Green Growth”, “Build Back Better”, “Green Deal” – the slogans varied, but they all expressed green modernisation as the common centrist response to the crisis.

Seeing 2020 as a comprehensive crisis of the neoliberal era – with regard to its environmental, social, economic and political underpinnings – helps us find our historical bearings. Seen in those terms, the coronavirus crisis marks the end of an arc whose origin is to be found in the 70s. It might also be seen as the first comprehensive crisis of the age of the Anthropocene – an era defined by the blowback from our unbalanced relationship to nature.

The year 2020 exposed how dependent economic activity was on the stability of the natural environment. A tiny virus mutation in a microbe could threaten the entire world’s economy. It also exposed how, in extremis, the entire monetary and financial system could be directed toward supporting markets and livelihoods. This forced the question of who was supported and how – which workers, which businesses would receive what benefits or which tax break? These developments tore down partitions that had been fundamental to the political economy of the last half-century – lines that divided the economy from nature, economics from social policy and from politics per se. On top of that, there was another major shift, which in 2020 finally dissolved the underlying assumptions of the era of neoliberalism: the rise of China.

When in 2005 Tony Blair scoffed at critics of globalisation, it was their fears that he mocked. He contrasted their parochial anxieties to the modernising energy of Asian nations, for which globalisation offered a bright horizon. The global security threats that Blair recognised, such as Islamic terrorism, were nasty. But they had no hope of actually changing the status quo. Therein lay their suicidal, otherworldly irrationality. In the decade after 2008, it was that confidence in the robustness of the status quo that was lost.

Russia was the first to expose the fact that global economic growth might shift the balance of power. Fuelled by exports of oil and gas, Moscow re-emerged as a challenge to US hegemony. Putin’s threat, however, was limited. China’s was not. In December 2017, the US issued its new National Security Strategy, which for the first time designated the Indo-Pacific as the decisive arena of great power competition. In March 2019, the EU issued a strategy document to the same effect. The UK, meanwhile, performed an extraordinary about-face, from celebrating a new “golden era” of Sino-UK relations in 2015 to deploying an aircraft carrier to the South China Sea.

The scale of stabilising interventions in 2020 was impressive. It confirmed the basic insistence of the Green New Deal that if the will was there, democratic states did have the tools they needed to exercise control over the economy. This was, however, a double-edged realisation, because if these interventions were an assertion of sovereign power, they were driven by crisis. As in 2008, they served the interests of those who had the most to lose. This time, not just individual banks but entire markets were declared too big to fail. To break that cycle of crisis and stabilising, and to make economic policy into a true exercise in democratic sovereignty, would require root-and-branch reform. That would require a real power shift, and the odds were stacked against that.

The massive economic policy interventions of 2020, like those of 2008, were Janus-faced. On the one hand, their scale exploded the bounds of neoliberal restraint and their economic logic confirmed the basic diagnosis of interventionist macroeconomics back to Keynes. When an economy was spiralling into recession, one did not have to accept the disaster as a natural cure, an invigorating purge. Instead, prompt and decisive government economic policy could prevent the collapse and forestall unnecessary unemployment, waste and social suffering.

These interventions could not but appear as harbingers of a new regime beyond neoliberalism. On the other hand, they were made from the top down. They were politically thinkable only because there was no challenge from the left and their urgency was impelled by the need to stabilise the financial system. And they delivered. Over the course of 2020, household net worth in the US increased by more than $15tn. Yet that overwhelmingly benefited the top 1%, who owned almost 40% of all stocks. The top 10%, between them, owned 84%. If this was indeed a “new social contract”, it was an alarmingly one-sided affair.

Nevertheless, 2020 was a moment not just of plunder, but of reformist experimentation. In response to the threat of social crisis, new modes of welfare provision were tried out in Europe, the US and many emerging market economies. And in search of a positive agenda, centrists embraced environmental policy and the issue of the climate crisis as never before. Contrary to the fear that Covid-19 would distract from other priorities, the political economy of the Green New Deal went mainstream. “Green Growth”, “Build Back Better”, “Green Deal” – the slogans varied, but they all expressed green modernisation as the common centrist response to the crisis.

Seeing 2020 as a comprehensive crisis of the neoliberal era – with regard to its environmental, social, economic and political underpinnings – helps us find our historical bearings. Seen in those terms, the coronavirus crisis marks the end of an arc whose origin is to be found in the 70s. It might also be seen as the first comprehensive crisis of the age of the Anthropocene – an era defined by the blowback from our unbalanced relationship to nature.

The year 2020 exposed how dependent economic activity was on the stability of the natural environment. A tiny virus mutation in a microbe could threaten the entire world’s economy. It also exposed how, in extremis, the entire monetary and financial system could be directed toward supporting markets and livelihoods. This forced the question of who was supported and how – which workers, which businesses would receive what benefits or which tax break? These developments tore down partitions that had been fundamental to the political economy of the last half-century – lines that divided the economy from nature, economics from social policy and from politics per se. On top of that, there was another major shift, which in 2020 finally dissolved the underlying assumptions of the era of neoliberalism: the rise of China.

When in 2005 Tony Blair scoffed at critics of globalisation, it was their fears that he mocked. He contrasted their parochial anxieties to the modernising energy of Asian nations, for which globalisation offered a bright horizon. The global security threats that Blair recognised, such as Islamic terrorism, were nasty. But they had no hope of actually changing the status quo. Therein lay their suicidal, otherworldly irrationality. In the decade after 2008, it was that confidence in the robustness of the status quo that was lost.

Russia was the first to expose the fact that global economic growth might shift the balance of power. Fuelled by exports of oil and gas, Moscow re-emerged as a challenge to US hegemony. Putin’s threat, however, was limited. China’s was not. In December 2017, the US issued its new National Security Strategy, which for the first time designated the Indo-Pacific as the decisive arena of great power competition. In March 2019, the EU issued a strategy document to the same effect. The UK, meanwhile, performed an extraordinary about-face, from celebrating a new “golden era” of Sino-UK relations in 2015 to deploying an aircraft carrier to the South China Sea.

Joe Biden in July 2020 during his presidential campaign.

Photograph: Olivier Douliery/AFP/Getty Images

The military logic was familiar. All great powers are rivals, or at least so goes the logic of “realist” thinking. In the case of China, there was the added factor of ideology. In 2021, the CCP did something its Soviet counterpart never got to do: it celebrated its centenary. While since the 80s it had permitted market-driven growth and private capital accumulation, Beijing made no secret of its adherence to an ideological heritage that ran by way of Marx and Engels to Lenin, Stalin and Mao. Xi Jinping could hardly have been more emphatic about the need to cleave to this tradition, and no clearer in his condemnation of Mikhail Gorbachev for losing hold of the Soviet Union’s ideological compass. So the “new” cold war was really the “old” cold war revived, the cold war in Asia, the one that the west had in fact never won.

There were, however, two major differences dividing the past from the present. The first was the economy. China posed a threat as a result of the greatest economic boom in history. That had hurt some workers in the west in manufacturing, but businesses and consumers across the western world and beyond had profited immensely from China’s development, and stood to profit even more in future. That created a quandary. A revived cold war with China made sense from every vantage point except “the economy, stupid”.

The second fundamental novelty was the global environmental problem, and the role of economic growth in accelerating it. When global climate politics first emerged in its modern form in the 90s, the US was the largest and most recalcitrant polluter. China was poor and its emissions barely figured in the global balance. By 2020, China emitted more carbon dioxide than the US and Europe put together, and the gap was poised to widen at least for another decade. You could no more envision a solution to the climate problem without China than you could imagine a response to the risk of emerging infectious diseases. China was the most powerful incubator of both.

In 2020, the green modernisers of the EU were still trying to resolve this double dilemma in their strategic documents by defining China all at the same time as a systemic rival, a strategic competitor and a partner in dealing with the climate crisis. The Trump administration made life easier for itself by denying the climate problem. But Washington, too, was impaled on the horns of the economic dilemma – between ideological denunciation of Beijing, strategic calculation, long-term corporate investments in China and the president’s desire to strike a quick deal. This was an unstable combination, and in 2020 it tipped. China was redefined as a threat to the US, strategically and economically. In reaction, the intelligence, security and judicial branches of the American government declared economic war on China. By closing markets and blocking the export of microchips and the equipment to make microchips, they set out to sabotage the development of China’s hi-tech sector, the heart of any modern economy.

It was to a degree accidental that this escalation took place when it did. China’s rise was a long-term world historic shift. But Beijing’s success in handling the coronavirus and the assertiveness that it unleashed were a red flag to the Trump administration. Meanwhile, it was growing increasingly clear that the US’s continued global strength in finance, tech and military power rested on domestic feet of clay. As Covid-19 painfully exposed, the US health system was ramshackle and its domestic social safety net left tens of millions at risk of poverty. If Xi’s “China dream” came through 2020 intact, the same cannot be said for its American counterpart.

The general crisis of neoliberalism in 2020 thus had a specific and traumatic significance for the US – and for one part of the American political spectrum in particular. The Republican party and its nationalist and conservative constituencies suffered in 2020 what can best be described as an existential crisis, with profoundly damaging consequences for the American government, for the American constitution and for America’s relations with the wider world. This culminated in the extraordinary period between 3 November 2020 and 6 January 2021, in which Trump refused to concede electoral defeat, a large part of the Republican party actively supported an effort to overturn the election, the social crisis and the pandemic were left unattended to, and finally, on 6 January, the president and other leading figures in his party encouraged a mob invasion of the Capitol.

For good reason, this raises deep concerns about the future of American democracy. And there are elements on the far right of American politics that can fairly be described as fascistoid. But two basic elements were missing from the original fascist equation in the US in 2020. One is total war. Americans remember the civil war and imagine future civil wars to come. They have recently engaged in expeditionary wars that have blown back on American society in militarised policing and paramilitary fantasies. But total war reconfigures society in quite a different way. It constitutes a mass body, not the individualised commandos of 2020.

The other missing ingredient in the classic fascist equation is social antagonism – a threat from the left, whether imagined or real, to the social and economic status quo. As the constitutional storm clouds gathered in 2020, American business aligned massively and squarely against Trump. Nor were the major voices of corporate America afraid to spell out the business case for doing so, including shareholder value, the problems of running companies with politically divided workforces, the economic importance of the rule of law and, astonishingly, the losses in sales to be expected in the event of a civil war.

The military logic was familiar. All great powers are rivals, or at least so goes the logic of “realist” thinking. In the case of China, there was the added factor of ideology. In 2021, the CCP did something its Soviet counterpart never got to do: it celebrated its centenary. While since the 80s it had permitted market-driven growth and private capital accumulation, Beijing made no secret of its adherence to an ideological heritage that ran by way of Marx and Engels to Lenin, Stalin and Mao. Xi Jinping could hardly have been more emphatic about the need to cleave to this tradition, and no clearer in his condemnation of Mikhail Gorbachev for losing hold of the Soviet Union’s ideological compass. So the “new” cold war was really the “old” cold war revived, the cold war in Asia, the one that the west had in fact never won.

There were, however, two major differences dividing the past from the present. The first was the economy. China posed a threat as a result of the greatest economic boom in history. That had hurt some workers in the west in manufacturing, but businesses and consumers across the western world and beyond had profited immensely from China’s development, and stood to profit even more in future. That created a quandary. A revived cold war with China made sense from every vantage point except “the economy, stupid”.

The second fundamental novelty was the global environmental problem, and the role of economic growth in accelerating it. When global climate politics first emerged in its modern form in the 90s, the US was the largest and most recalcitrant polluter. China was poor and its emissions barely figured in the global balance. By 2020, China emitted more carbon dioxide than the US and Europe put together, and the gap was poised to widen at least for another decade. You could no more envision a solution to the climate problem without China than you could imagine a response to the risk of emerging infectious diseases. China was the most powerful incubator of both.

In 2020, the green modernisers of the EU were still trying to resolve this double dilemma in their strategic documents by defining China all at the same time as a systemic rival, a strategic competitor and a partner in dealing with the climate crisis. The Trump administration made life easier for itself by denying the climate problem. But Washington, too, was impaled on the horns of the economic dilemma – between ideological denunciation of Beijing, strategic calculation, long-term corporate investments in China and the president’s desire to strike a quick deal. This was an unstable combination, and in 2020 it tipped. China was redefined as a threat to the US, strategically and economically. In reaction, the intelligence, security and judicial branches of the American government declared economic war on China. By closing markets and blocking the export of microchips and the equipment to make microchips, they set out to sabotage the development of China’s hi-tech sector, the heart of any modern economy.

It was to a degree accidental that this escalation took place when it did. China’s rise was a long-term world historic shift. But Beijing’s success in handling the coronavirus and the assertiveness that it unleashed were a red flag to the Trump administration. Meanwhile, it was growing increasingly clear that the US’s continued global strength in finance, tech and military power rested on domestic feet of clay. As Covid-19 painfully exposed, the US health system was ramshackle and its domestic social safety net left tens of millions at risk of poverty. If Xi’s “China dream” came through 2020 intact, the same cannot be said for its American counterpart.

The general crisis of neoliberalism in 2020 thus had a specific and traumatic significance for the US – and for one part of the American political spectrum in particular. The Republican party and its nationalist and conservative constituencies suffered in 2020 what can best be described as an existential crisis, with profoundly damaging consequences for the American government, for the American constitution and for America’s relations with the wider world. This culminated in the extraordinary period between 3 November 2020 and 6 January 2021, in which Trump refused to concede electoral defeat, a large part of the Republican party actively supported an effort to overturn the election, the social crisis and the pandemic were left unattended to, and finally, on 6 January, the president and other leading figures in his party encouraged a mob invasion of the Capitol.

For good reason, this raises deep concerns about the future of American democracy. And there are elements on the far right of American politics that can fairly be described as fascistoid. But two basic elements were missing from the original fascist equation in the US in 2020. One is total war. Americans remember the civil war and imagine future civil wars to come. They have recently engaged in expeditionary wars that have blown back on American society in militarised policing and paramilitary fantasies. But total war reconfigures society in quite a different way. It constitutes a mass body, not the individualised commandos of 2020.

The other missing ingredient in the classic fascist equation is social antagonism – a threat from the left, whether imagined or real, to the social and economic status quo. As the constitutional storm clouds gathered in 2020, American business aligned massively and squarely against Trump. Nor were the major voices of corporate America afraid to spell out the business case for doing so, including shareholder value, the problems of running companies with politically divided workforces, the economic importance of the rule of law and, astonishingly, the losses in sales to be expected in the event of a civil war.

Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez campaigning in 2019.

Photograph: Michael Reynolds/EPA

This alignment of money with democracy in the US in 2020 should be reassuring, but only up to a point. Consider for a second an alternative scenario. What if the virus had arrived in the US a few weeks sooner, the spreading pandemic had rallied mass support for Bernie Sanders and his call for universal health care, and the Democratic primaries had swept an avowed socialist to the head of the ticket rather than Joe Biden? It is not difficult to imagine a scenario in which the full weight of American business was thrown the other way, for all the same reasons, backing Trump in order to ensure that Sanders was not elected. And what if Sanders had in fact won a majority? Then we would have had a true test of the American constitution and the loyalty of the most powerful social interests to it. The fact that we have to contemplate such scenarios is indicative of the extremity of the polycrisis of 2020.

The election of Joe Biden and the fact that his inauguration took place at the appointed time on 21 January 2021 restored a sense of calm. But when Biden boldly declares that “America is back”, it has become increasingly clear that the next question we need to ask is: which America? And back to what? The comprehensive crisis of neoliberalism may have unleashed creative intellectual energy even at the once-dead centre of politics. But an intellectual crisis does not a new era make. If it is energising to discover that we can afford anything we can actually do, it also puts us on the spot. What can and should we actually do? Who, in fact, is the we?

As Britain, the US and Brazil demonstrate, democratic politics is taking on strange and unfamiliar new forms. Social inequalities are more, not less extreme. At least in the rich countries, there is no collective countervailing force. Capitalist accumulation continues in channels that continuously multiply risks. The principal use to which our newfound financial freedom has been put are more and more grotesque efforts at financial stabilisation. The antagonism between the west and China divides huge chunks of the world, as not since the cold war. And now, in the form of Covid, the monster has arrived. The Anthropocene has shown its fangs – on an as yet modest scale. Covid is far from being the worst of what we should expect – 2020 was not the full alert. If we are dusting ourselves off and enjoying the recovery, we should reflect. Around the world the dead are unnumbered, but our best guess puts the figure at 10 million. Thousands are dying every day. And 2020 was a wake-up call.

Adapted from Shutdown: How Covid Shook the World’s Economy by Adam Tooze, published by Allen Lane on 7 September.

This alignment of money with democracy in the US in 2020 should be reassuring, but only up to a point. Consider for a second an alternative scenario. What if the virus had arrived in the US a few weeks sooner, the spreading pandemic had rallied mass support for Bernie Sanders and his call for universal health care, and the Democratic primaries had swept an avowed socialist to the head of the ticket rather than Joe Biden? It is not difficult to imagine a scenario in which the full weight of American business was thrown the other way, for all the same reasons, backing Trump in order to ensure that Sanders was not elected. And what if Sanders had in fact won a majority? Then we would have had a true test of the American constitution and the loyalty of the most powerful social interests to it. The fact that we have to contemplate such scenarios is indicative of the extremity of the polycrisis of 2020.

The election of Joe Biden and the fact that his inauguration took place at the appointed time on 21 January 2021 restored a sense of calm. But when Biden boldly declares that “America is back”, it has become increasingly clear that the next question we need to ask is: which America? And back to what? The comprehensive crisis of neoliberalism may have unleashed creative intellectual energy even at the once-dead centre of politics. But an intellectual crisis does not a new era make. If it is energising to discover that we can afford anything we can actually do, it also puts us on the spot. What can and should we actually do? Who, in fact, is the we?

As Britain, the US and Brazil demonstrate, democratic politics is taking on strange and unfamiliar new forms. Social inequalities are more, not less extreme. At least in the rich countries, there is no collective countervailing force. Capitalist accumulation continues in channels that continuously multiply risks. The principal use to which our newfound financial freedom has been put are more and more grotesque efforts at financial stabilisation. The antagonism between the west and China divides huge chunks of the world, as not since the cold war. And now, in the form of Covid, the monster has arrived. The Anthropocene has shown its fangs – on an as yet modest scale. Covid is far from being the worst of what we should expect – 2020 was not the full alert. If we are dusting ourselves off and enjoying the recovery, we should reflect. Around the world the dead are unnumbered, but our best guess puts the figure at 10 million. Thousands are dying every day. And 2020 was a wake-up call.

Adapted from Shutdown: How Covid Shook the World’s Economy by Adam Tooze, published by Allen Lane on 7 September.