Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, promised that the Trump administration wouldn't strike

Author of the article:

Isaac Stanley-Becker

Publishing date:Sep 14, 2021 •

Twice in the final months of the Trump administration, the country’s top military officer was so fearful that the president’s actions might spark a war with China that he moved urgently to avert armed conflict.

In a pair of secret phone calls, Gen. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, assured his Chinese counterpart, Gen. Li Zuocheng of the People’s Liberation Army, that the United States would not strike, according to a new book by Washington Post associate editor Bob Woodward and national political reporter Robert Costa.

One call took place on Oct. 30, 2020, four days before the election that unseated President Donald Trump, and the other on Jan. 8, 2021, two days after the Capitol siege carried out by his supporters in a quest to cancel the vote.

The first call was prompted by Milley’s review of intelligence suggesting the Chinese believed the U.S. was preparing to attack. That belief, the authors write, was based on tensions over military exercises in the South China Sea, and deepened by Trump’s belligerent rhetoric toward China.

“General Li, I want to assure you that the American government is stable and everything is going to be OK,” Milley told him. “We are not going to attack or conduct any kinetic operations against you.”

In the book’s telling, Milley went so far as to pledge he would alert his counterpart in the event of a U.S. attack, stressing the rapport they’d established through a backchannel. “General Li, you and I have known each other for now five years. If we’re going to attack, I’m going to call you ahead of time. It’s not going to be a surprise.”

If we're going to attack, I'm going to call you ahead of time

MARK MILLEY, CHAIRMAN, JOINT CHIEFS OF STAFF

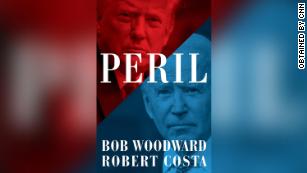

Li took the chairman at his word, the authors write in the book, Peril, which is set to be released next week.

In the second call, placed to address Chinese fears about the events of Jan. 6, Li wasn’t as easily assuaged, even after Milley promised him, “We are 100 per cent steady. Everything’s fine. But democracy can be sloppy sometimes.”

Li remained rattled, and Milley, who, according to the book, did not relay the conversation to Trump, understood why. The chairman, 62 at the time and chosen by Trump in 2018, believed the president had suffered a mental decline after the election, the authors write, a view he communicated to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi in a phone call on Jan. 8. He agreed with her evaluation that Trump was unstable, according to a call transcript obtained by the authors.

Believing that China could lash out if it felt at risk from an unpredictable and vengeful American president, Milley took action. The same day, he called the admiral overseeing the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, the military unit responsible for Asia and the Pacific region, and recommended postponing the military exercises, according to the book. The admiral complied.

Milley also summoned senior officers to review the procedures for launching nuclear weapons, saying the president alone could give the order — but, crucially, that he, Milley, also had to be involved. Looking each in the eye, Milley asked the officers to affirm that they had understood, the authors write, in what he considered an “oath.”

The chairman knew that he was “pulling a Schlesinger,” the authors write, resorting to measures resembling the ones taken in August 1974 by James Schlesinger, the secretary of defence at the time. Schlesinger told military officials to check with him and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs before carrying out orders from President Richard Nixon, who was facing impeachment at the time.

Though Milley went furthest in seeking to stave off a national security crisis, his alarm was shared throughout the highest ranks of the administration, the authors reveal. CIA Director Gina Haspel, for instance, reportedly told Milley, “We are on the way to a right-wing coup.”

The book also provides fresh reporting on President Joe Biden’s campaign — waged to unseat a man he told a top adviser “isn’t really an American president” — and his early struggle to govern. During a March 5 phone call to discuss Biden’s $1.9 trillion stimulus plan, his first major legislative undertaking, the president reportedly told Sen. Joe Manchin III, D-W.Va., “if you don’t come along, you’re really f—ing me.” The measure ultimately cleared the Senate through an elaborate sequencing of amendments designed to satisfy the centrist Democrat.

The president’s frustration with Manchin is matched only by his debt to House Majority Whip Rep. James Clyburn of South Carolina, whose endorsement before that state’s primary propelled Biden to the nomination and gave rise to promises about how he would govern.

When Clyburn offered his endorsement in February 2020, it came with conditions, according to the book. One was that Biden would commit to naming a Black woman to the Supreme Court, if given the opportunity. During a debate two days later, Clyburn went backstage during a break to urge Biden to reveal his intentions for the Supreme Court that night. Biden issued the pledge in his final answer, and the congressman endorsed him the next day.

Peril, the authors say, is based on interviews with more than 200 people

Peril, the authors say, is based on interviews with more than 200 people, conducted on the condition they not be named as sources. Exact quotations or conclusions are drawn from the participant in the described event, a colleague with direct knowledge or relevant documents, according to an author’s note. Trump and Biden declined to be interviewed.

On Afghanistan, the book examines how Biden’s experience as vice-president shaped his approach to the withdrawal. Convinced that President Barack Obama had been manipulated by his own commanders, Biden vowed privately in 2009, “The military doesn’t f— around with me.”

It also documents how Biden’s top advisers spent the spring weighing, but ultimately rejecting, alternatives to a full withdrawal. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin returned from a NATO meeting in March envisioning ways to extend the mission, including through a “gated” withdrawal seeking diplomatic leverage. But they came to see that meaningful leverage would require a more expansive commitment, and instead came back around to a full exit.

Milley took a deferential approach to Biden on Afghanistan, in contrast to his earlier efforts to constrain Trump

Milley, for his part, took what the authors describe as a deferential approach to Biden on Afghanistan, in contrast to his earlier efforts to constrain Trump. The book reveals recent remarks the chairman delivered to the Joint Chiefs in which he said, “Here’s a couple of rules of the road here that we’re going to follow. One is you never, ever, ever box in a president of the United States. You always give him decision space.” Referring to Biden, he said, “You’re dealing with a seasoned politician here who has been in Washington, D.C., 50 years, whatever it is.”

His decision just months earlier to place himself between Trump and potential war was triggered by several important events — a phone call, a photo op and a refusal to rule out war with another adversary, Iran.

The immediate motivation, according to the book, was the Jan. 8 call from Pelosi, who demanded to know, “What precautions are available to prevent an unstable president from initiating military hostilities or from accessing the launch codes and ordering a nuclear strike?” Milley assured her that there were “a lot of checks in the system.”

The call transcript obtained by the authors shows Pelosi telling Milley, referring to Trump, “He’s crazy. You know he’s crazy. … He’s crazy and what he did yesterday is further evidence of his craziness.” Milley replied, “I agree with you on everything.”

Milley’s resolve was deepened by the events of June 1, 2020 when he felt Trump had used him as part of a photo op in his walk across Lafayette Square during protests that began after the killing of George Floyd. The chairman came to see his role as ensuring that, “We’re not going to turn our guns on the American people and we’re not going to have a ‘Wag the Dog’ scenario overseas,” the authors quote him saying privately.

Trump’s posture, not just to China but also to Iran, tested that promise. In discussions about Iran’s nuclear program, Trump declined to rule out striking the country, at times even displaying curiosity about the prospect, according to the book. Haspel was so alarmed after a meeting in November that she called Milley to say, “This is a highly dangerous situation. We are going to lash out for his ego?”

Mike, you have no flexibility on this. None. Zero. Forget it. Put it away

DAN QUAYLE TO THEN VICE-PRESIDENT MIKE PENCE ABOUT NOT CERTIFYING THE ELECTION RESULT

Trump’s fragile ego drove many decisions by the nation’s leaders, from lawmakers to the vice-president, according to the book. Sen. Mitch McConnell was so worried that a call from President-elect Biden would send Trump into a fury that the then-Majority Leader used a backchannel to fend off Biden. He asked Sen. John Cornyn of Texas, formerly the No. 2 Senate Republican, to ask Sen. Christopher Coons, the Democrat of Delaware and close Biden ally, to tell Biden not to call him.

So intent was Pence on being Trump’s loyal second-in-command — and potential successor — that he asked confidants if there were ways he could accede to Trump’s demands and avoid certifying the results of the election on Jan. 6. In late December, the authors reveal, Pence called Dan Quayle, a former vice-president and fellow Indiana Republican, for advice.

Quayle was adamant, according to the authors. “Mike, you have no flexibility on this. None. Zero. Forget it. Put it away,” he said.

But Pence pressed him, the authors write, asking if there were any grounds to pause the certification because of ongoing legal challenges. Quayle was unmoved, and Pence ultimately agreed, according to the book.

I don't want to be your friend anymore if you don't do thisTHEN-PRESIDENT TRUMP TO MIKE PENCE

When Pence said he planned to certify the results, the president lashed out. In the Oval Office on Jan. 5, the authors write, Pence told Trump he could not thwart the process, that his role was simply to “open the envelopes.”

“I don’t want to be your friend anymore if you don’t do this,” Trump replied, according to the book, later telling his vice-president, “You’ve betrayed us. I made you. You were nothing.”

Within days, Trump was out of office, his governing power reduced to nothing. But if stability had returned to Washington, Milley feared it would be short-lived, the authors write.

The general saw parallels between Jan. 6 and the 1905 Russian Revolution, which set off unrest throughout the Russian Empire and, though it failed, helped create the conditions for the October Revolution of 1917, in which the Bolsheviks executed a successful coup that set up the world’s first communist state. Vladimir Lenin, who led the revolution, called 1905 a “dress rehearsal.”

A similar logic could apply with Jan. 6, Milley thought as he wrestled with the meaning of that day, telling senior staff: “What you might have seen was a precursor to something far worse down the road.

Top general so fearful Donald Trump might spark war that he made secret calls to Chinese counterpart, new book says

QILAI SHEN/BLOOMBERG

US President Donald Trump, and Xi Jinping, China's president, shaking hands during a news conference at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on November 9, 2017.

Twice in the final months of the Trump administration, the US’ top military officer was so fearful that the president's actions might spark a war with China that he moved urgently to avert armed conflict.

In a pair of secret phone calls, General Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, assured his Chinese counterpart, General Li Zuocheng of the People's Liberation Army, that the United States would not strike, according to a new book by Washington Post associate editor Bob Woodward and national political reporter Robert Costa.

One call took place on October 30, 2020, four days before the election that unseated President Donald Trump, and the other on January 8, 2021, two days after the Capitol siege carried out by his supporters in a quest to cancel the vote.

The first call was prompted by Milley's review of intelligence suggesting the Chinese believed the United States was preparing to attack. That belief, the authors write, was based on tensions over military exercises in the South China Sea, and deepened by Trump's belligerent rhetoric toward China.

General Mark Milley said accompanying the president for a photo op preceded by a violent crackdown on protesters created the perception "of the military involved in domestic politics". (Published June 2020)

“General Li, I want to assure you that the American government is stable and everything is going to be OK,” Milley told him. “We are not going to attack or conduct any kinetic operations against you.”

In the book's telling, Milley went so far as to pledge he would alert his counterpart in the event of a US attack, stressing the rapport they'd established through a backchannel. “General Li, you and I have known each other for now five years. If we're going to attack, I'm going to call you ahead of time. It's not going to be a surprise.”

Li took the chairman at his word, the authors write in the book, Peril, which is set to be released next week.

In the second call, placed to address Chinese fears about the events of January 6, Li wasn't as easily assuaged, even after Milley promised him, “We are 100 per cent steady. Everything's fine. But democracy can be sloppy sometimes.”

Li remained rattled, and Milley, who did not relay the conversation to Trump, according to the book, understood why.

The chairman, 62 at the time and chosen by Trump in 2018, believed the president had suffered a mental decline after the election, the authors write, a view he communicated to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi in a phone call on January 8. He agreed with her evaluation that Trump was unstable, according to a call transcript obtained by the authors.

SUSAN WALSH/AP

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley.

Believing that China could lash out if it felt at risk from an unpredictable and vengeful American president, Milley took action. The same day, he called the admiral overseeing the US Indo-Pacific Command, the military unit responsible for Asia and the Pacific region, and recommended postponing the military exercises, according to the book. The admiral complied.

Milley also summoned senior officers to review the procedures for launching nuclear weapons, saying the president alone could give the order – but, crucially, that he, Milley, also had to be involved. Looking each in the eye, Milley asked the officers to affirm that they had understood, the authors write, in what he considered an “oath”.

The chairman knew that he was “pulling a Schlesinger,” the authors write, resorting to measures resembling the ones taken in August 1974 by James Schlesinger, the secretary of defence at the time. Schlesinger told military officials to check with him and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs before carrying out orders from President Richard Nixon, who was facing impeachment at the time.

Though Milley went furthest in seeking to stave off a national security crisis, his alarm was shared throughout the highest ranks of the administration, the authors reveal. CIA Director Gina Haspel, for instance, reportedly told Milley, “We are on the way to a right-wing coup.”

The book also provides fresh reporting on President Joe Biden's campaign – waged to unseat a man he told a top adviser “isn't really an American president” – and his early struggle to govern.

EVAN VUCCI/AP

The book also provides fresh reporting on President Joe Biden's campaign and his early struggle to govern. (File photo)

During a March 5 phone call to discuss Biden's US$1.9 trillion stimulus plan, his first major legislative undertaking, the president reportedly told Senator Joe Manchin III, “if you don't come along, you're really f...ing me”. The measure ultimately cleared the Senate through an elaborate sequencing of amendments designed to satisfy the centrist Democrat.

The president's frustration with Manchin is matched only by his debt to House Majority Whip Representative James Clyburn of South Carolina, whose endorsement before that state's primary propelled Biden to the nomination and gave rise to promises about how he would govern.

When Clyburn offered his endorsement in February 2020, it came with conditions, according to the book. One was that Biden would commit to naming a Black woman to the Supreme Court, if given the opportunity. During a debate two days later, Clyburn went backstage during a break to urge Biden to reveal his intentions for the Supreme Court that night. Biden issued the pledge in his final answer, and the congressman endorsed him the next day.

Peril, the authors say, is based on interviews with more than 200 people, conducted on the condition they not be named as sources. Exact quotations or conclusions are drawn from the participant in the described event, a colleague with direct knowledge or relevant documents, according to an author's note. Trump and Biden declined to be interviewed.

On Afghanistan, the book examines how Biden's experience as vice president shaped his approach to the withdrawal. Convinced that President Barack Obama had been manipulated by his own commanders, Biden vowed privately in 2009, “The military doesn't f... around with me.”

ALEX WONG/GETTY IMAGES

The book examines how Joe Biden's experience as vice president during the Obama administration shaped his approach to the Afghanistan withdrawal. (File photo)

It also documents how Biden's top advisers spent the spring weighing, but ultimately rejecting, alternatives to a full withdrawal. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin returned from a NATO meeting in March envisioning ways to extend the mission, including through a “gated” withdrawal seeking diplomatic leverage. But they came to see that meaningful leverage would require a more expansive commitment, and instead came back around to a full exit.

Milley, for his part, took what the authors describe as a deferential approach to Biden on Afghanistan, in contrast to his earlier efforts to constrain Trump. The book reveals recent remarks the chairman delivered to the Joint Chiefs in which he said, “Here's a couple of rules of the road here that we're going to follow. One is you never, ever ever box in a president of the United States. You always give him decision space.” Referring to Biden, he said, “You're dealing with a seasoned politician here who has been in Washington, DC, 50 years, whatever it is.”

His decision just months earlier to place himself between Trump and potential war was triggered by several important events – a phone call, a photo op and a refusal to rule out war with another adversary, Iran.

The immediate motivation, according to the book, was the January 8 call from Pelosi, who demanded to know, “What precautions are available to prevent an unstable president from initiating military hostilities or from accessing the launch codes and ordering a nuclear strike?” Milley assured her that there were “a lot of checks in the system”.

The call transcript obtained by the authors shows Pelosi telling Milley, referring to Trump, “He's crazy. You know he's crazy. ... He's crazy and what he did yesterday is further evidence of his craziness.” Milley replied, “I agree with you on everything.”

By Jamie Gangel, Jeremy Herb and Elizabeth Stuart,

Tue September 14, 2021

The story below contains explicit language.

Washington (CNN)Just eight days after the 2020 election, then-President Donald Trump was so determined to end the war in Afghanistan during his presidency that he secretly signed a memo to withdraw all troops by January 15, 2021, according to a new book, "Peril," from journalists Bob Woodward and Robert Costa.

The November 11 memo, according to the authors, had been secretly drafted by two Trump loyalists and never went through the normal process for a military directive -- the secretary of defense, national security adviser and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs had all never seen it. Unpredictable, impulsive, Trump had done an end run around his whole national security team.

In a remarkable scene, the authors write, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen. Mark Milley, newly appointed acting Defense Secretary Chris Miller and his new chief of staff Kash Patel were all blindsided when the memo arrived at the Pentagon.

Woodward and Costa reproduced the memo in "Peril." The directive was titled, "Memorandum for the Acting Secretary of Defense: Withdrawal from Somalia and Afghanistan," and the memo read: "I hereby direct you to withdraw all US forces from the Federal Republic of Somalia no later than 31 December 2020 and from the Islamic Republican of Afghanistan no later than 15 January 2021. Inform all allied and partner forces of the directives. Please confirm receipt of this order."

Milley studied the memo and announced he was heading to the White House to confront Trump.

Woodward book: Worried Trump could 'go rogue,' Milley took top-secret action to protect nuclear weapons

"This is really fucked up and I'm going to see the President. I'm heading over. You guys can come or not," Milley told Miller and Patel, who joined him on the trip across the Potomac, according to the book.

Enter your email to sign up for CNN's "Meanwhile in China" Newsletter.

close dialog

At the White House, the three men paid a surprise visit to national security adviser Robert O'Brien and showed him the signed memo.

"How did this happen?" Milley asked O'Brien, according to the book. "Was there any process here at all? How does a president do this?"

O'Brien looked at the memo and said, "I have no idea," according to the authors.

"What do you mean you have no idea? You're the national security adviser to the President?" Milley responded. "And the secretary of defense didn't know about this? And the chief of staff to the secretary of defense didn't know about this? The chairman didn't know. How the hell does this happen?"

O'Brien took the memo and left. While the officials had briefly debated whether the memo could be a forgery, Trump confirmed to O'Brien that he had signed it.

"Mr. President, you've got to have a meeting with the principals," O'Brien told Trump, according to the book, which Trump agreed to do and the directive was withdrawn.

President Donald J. Trump talks with others in the Oval Office at the White House on Friday, November 13, 2020.

It was "effectively a rogue memo and had no standing," Woodward and Costa write. "All right," O'Brien said when he returned to his office. "We've already taken care of this. It was a mistake. The memo was nullified."

But the signed rogue memo undercuts the argument that Trump and some of his allies, including Miller, have recently made that Trump never really planned to get out or would have planned the withdrawal better than President Joe Biden.

"If I were now President, the world would find that our withdrawal from Afghanistan would be a conditions-based withdrawal," Trump said in a statement last month as the Taliban closed in on Kabul. "I personally had discussions with top Taliban leaders whereby they understood what they are doing now would not have been acceptable."

Exclusive: Title, cover and details of new Trump book from Bob Woodward and Robert Costa revealed

Axios' Jonathan Swan and Zachary Basu reported in May that the memo had been drafted by two Trump loyalists who should not have been involved in the process -- Johnny McEntee, the former body man who Trump had named head of White House personnel, and controversial retired Lt. Col. Douglas Macgregor, who had just been appointed as an adviser to Miller.

Woodward and Costa write in "Peril" that the memo was also one of the reasons Milley was concerned Trump could go rogue after the November election, and prompted Milley after the January 6 insurrection to take steps to try to limit Trump from launching military strikes or nuclear weapons unless he was consulted.

Eventually, Milley, Miller and Patel left the White House. They never saw the President that day, but after the January 6 assault on the Capitol, Woodward and Costa write that Milley "felt no absolute certainty that the military could control or trust Trump." Milley "believed it was his job as the senior military officer to think the unthinkable, take any and all necessary precautions."