Inspired by art, researchers find the finger snap to have the highest acceleration the human body produces

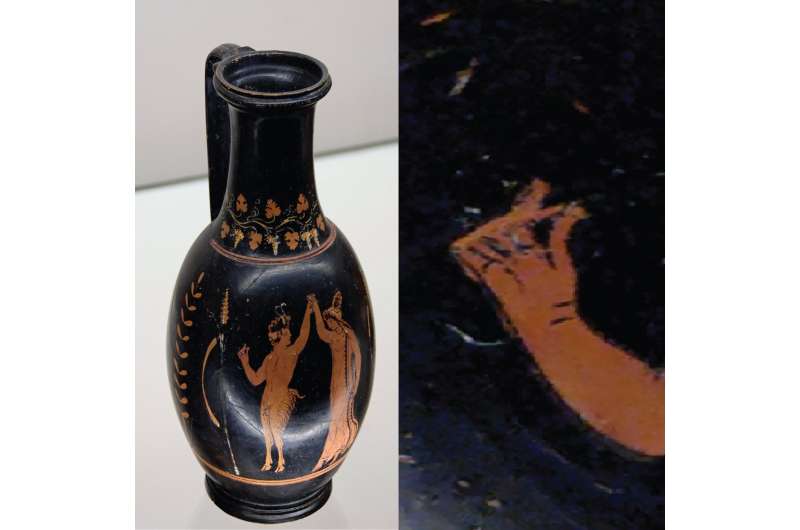

The snapping of a finger was first depicted in ancient Greek art around 300 B.C. Today, that same snap initiates evil forces for the villain Thanos in Marvel's latest Avengers movie. Both media inspired a group of researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology to study the physics of a finger snap and determine how friction plays a critical role.

Using an intermediate amount of friction, not too high and not too low, a snap of the finger produces the highest rotational accelerations observed in humans, even faster than the arm of a professional baseball pitcher. The results were published Nov. 17 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

The research was led by an undergraduate student at Georgia Tech, Raghav Acharya, as well as doctoral student Elio Challita, Assistant Professor Saad Bhamla of the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, and Assistant Professor Mark Ilton of Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, California.

Their results might one day inform the design of prosthetics meant to imitate the wide-ranging capabilities of the human hand. Bhamla said the project is also a prime example of what he calls curiosity-driven science, where everyday occurrences and biological behaviors can serve as data sources for new discoveries.

"For the past few years, I've been fascinated with how we can snap our fingers," Bhamla said. "It's really an extraordinary physics puzzle right at our fingertips that hasn't been investigated closely."

In earlier work, Bhamla, Ilton, and other colleagues had developed a general framework for explaining the surprisingly powerful and ultrafast motions observed in living organisms. The framework seemed to naturally apply to the snap. It posits that organisms depend on the use of a spring and latching mechanism to store up energy, which they can then quickly release.

Acharya and Bhamla felt a particular push to apply this framework to a finger snap after seeing the movie Avengers: Infinity War, released in April 2018 and produced by Marvel Studios. In it, Thanos, a villainous character, seeks to obtain six special stones and place them into his metal gauntlet. After collecting them all, he snaps his fingers and triggers universe-wide consequences.

But would it be possible to snap at all while wearing an armor gauntlet, the researchers asked? In the case of a finger snap, they suspected that skin friction played a more important role compared to other spring and latch systems. With the frictional properties of a metal gauntlet, they imagined it might be impossible.

Using high-speed imaging, automated image processing, and dynamic force sensors, the researchers analyzed a variety of finger snaps. They explored the role of friction by covering fingers with different materials, including metallic thimbles to simulate the effects of trying to snap while wearing a metallic gauntlet, much like Thanos.

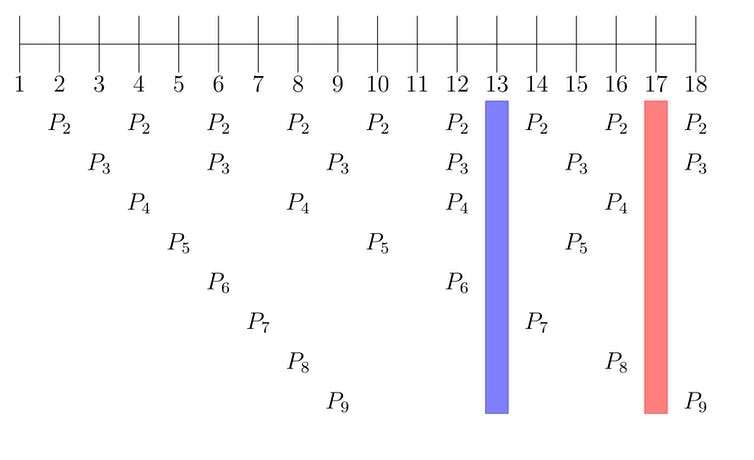

For an ordinary snap with bare fingers, the researchers measured maximal rotational velocities of 7,800 degrees per second and rotational accelerations of 1.6 million degrees per second squared. The rotational velocity is less than that measured for the fastest rotational motions observed in humans, which come from the arms of professional baseball players during the act of pitching. However, the snap acceleration is the fastest human angular acceleration yet measured, almost three times faster than the rotational acceleration of a professional baseball pitcher's arm.

"When I first saw the data, I jumped out of my chair," said Bhamla, who studies ultrafast motions in a variety of living systems, from single cells to insects. "The finger snap occurs in only seven milliseconds, more than twenty times faster than the blink of an eye, which takes more than 150 milliseconds."

When the fingertips of the subjects were covered with metal thimbles, their maximal rotational velocities decreased dramatically, confirming the researchers' intuitions.

"Our results suggest that Thanos could not have snapped because of his metal armored fingers," said Acharya, first author of the study. "So, it's probably the Hollywood special effects, rather than actual physics, at play! Sorry for the spoiler."

They explained this decrease by considering the diminished contact area that exists between thimble-covered fingers.

"The compression of the skin makes the system a little bit more fault tolerant," said Challita, a coauthor on the work. "Reducing both the compressibility and friction of the skin make it a lot harder to build up enough force in your fingers to actually snap."

Surprisingly, increasing the friction of the fingertips with rubber coverings also reduced speed and acceleration. The researchers concluded that a Goldilocks zone of friction was necessary—too little friction and not enough energy was stored to power the snap, and too much friction led to energy dissipation as the fingers took longer to slide past each other, wasting the stored energy into heat.

The researchers experimented with a variety of mathematical models of the snapping process to explain their observations. They found that a model including a spring and a soft friction contact-latch could reproduce the qualitative features of their results.

"We included soft frictional contact into our mathematical model, and the results reinforced the central role played by friction in achieving ultrafast motions," Ilton said. "This model can now help us understand how other animals such as termites and ants snap their mandibles, as well as rationally bioinspired actuators for engineering applications."

John Long, a program director in the National Science Foundation's Division of Integrative Organismal Systems, oversees research in the Physiological Mechanisms and Biomechanics Program, which currently funds Bhamla's investigations into ultrafast behaviors in animals.

"This research is a great example of what we can learn with clever experiments and insightful computational modeling," he said. "By showing that varying degrees of friction between the fingers alters the elastic performance of a snap, these scientists have opened the door to discovering the principles operating in other organisms, and to putting this mechanism to work in engineered systems such as bioinspired robots."

John Long, program director in the Directorate for Biological Sciences at the National Science Foundation, oversees research in the Physiological Mechanisms and Biomechanics Program, which currently funds Bhamla's investigations into ultrafast behaviors in animals.

"The research of Dr. Bhamla and his colleagues is a great example of what we can learn with clever experiments and insightful computational modeling," he said. "By showing that varying degrees of friction between the fingers alters the elastic performance of the snap, they've opened the door for discovering these principles operating in other organisms and for putting this soft, sophisticated, and adjustable mechanism to work in engineered systems such as bioinspired robots."

The researchers believe that the results open a variety of opportunities for future study, including understanding why humans snap at all, and if humans are the only primates to have evolved this physical ability.

"Based on ancient Greek art from 300 B.C., humans may very well have been snapping their fingers for hundreds of thousands of years before that, yet we are only now beginning to scientifically study it," Bhamla said. "This is the only scientific project in my lab in which we could snap our fingers and get data."New law of physics helps humans and robots grasp the friction of touch

]More information: The ultrafast snap of a finger is mediated by skin friction, Journal of the Royal Society Interface (2021). DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2021.0672. rsif.royalsocietypublishing.or … .1098/rsif.2021.0672

Journal information: Journal of the Royal Society Interface

Provided by Georgia Institute of Technology