Tech companies underreport CO2 emissions

Companies in the digital technology industry are significantly underreporting the greenhouse gas emissions arising along the value chain of their products. Across a sample of 56 major tech companies surveyed in a study by the Technical University of Munich (TUM), more than half of these emissions were excluded from self-reporting in 2019. At approximately 390 megatons carbon dioxide equivalents, the omitted emissions are in the same ballpark as the carbon footprint of Australia. The research team has developed a method for spotting sources of error and calculating the omitted disclosures.

For policy makers and the private sector to set targets for reduced greenhouse gas emissions, it is important to know how much CO2 companies are actually emitting. However, there are no binding requirements for comprehensive accounting and full disclosure of these emissions. The Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol is seen as a voluntary standard. It distinguishes three categories of emissions: Scope 1 refers to direct emissions from a company's own activities, scope 2 refers to emissions from the production of purchased energy, and scope 3 to emissions from activities along the value chain, in other words all emissions from raw material extraction to the use of the end product. Scope 3 emissions often represent the majority of a company's carbon footprint. Past studies have also shown that these emissions account for most reporting gaps. Until now, however, it was not possible to quantify these gaps or determine their causes.

Lena Klaaßen and Dr. Christian Stoll at the TUM School of Management of the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have developed a method for identifying reporting gaps for scope 3 emissions and used it in a case study to determine the carbon footprints of pre-selected digital technology companies. Their paper has now been published in the journal Nature Communications.

Companies publish inconsistent figures

Klaaßen and Stoll determined that many companies submit different greenhouse gas emission figures depending on where they are reporting them. They focused mainly on the companies' own reports as compared with voluntary disclosures to the non-profit organization CDP. The annual survey of companies conducted by CDP is regarded as the most important collection of data based on the structure of the GHG Protocol. Most companies disclose lower emissions in their own reports than in the CDP survey. This could be partly due to the fact that the CDP report is intended mainly for investors, while corporate reports are addressed to the general public.

In addition, CDP leaves it up to the reporting companies to choose which of the 15 GHG Protocol categories—ranging from business travel to waste disposal—are relevant to them. The studies show that this discretionary freedom results in some companies ignoring certain categories or not fully reporting the related emissions. Most companies have reporting gaps simply because they do not receive emissions data from all suppliers and do not fill the gaps with secondary data.

To close the gaps, Klaaßen and Stoll calculate the emissions by applying the values of several comparable companies which report complete figures. They take into account whether these companies are from the same industry and are comparable in terms of key indicators such as sales, profits and workforce size. To apply a uniform benchmark, they assume that GHG Protocol categories are relevant to a company unless it specifically states that emissions are non-existent in this area.

751 vs. 360 megatons of carbon dioxide equivalents

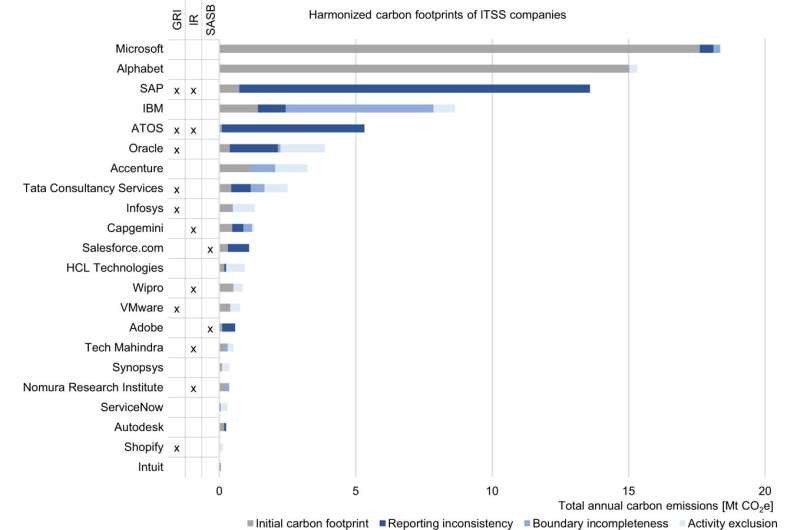

Klaaßen and Stoll applied this method to quantify the scope 3 emissions of 56 digital technology companies. Due to its high energy consumption, this industry is seen as a major source of CO2 emissions, but has frequently claimed that it is committed to a low-carbon business model. The case study investigates software and hardware manufacturers which were included in the 2019 Forbes Global 2000 list, ranking the world's largest public companies, and have participated in the CDP survey in the same year.

The calculations show that in 2019 the analyzed tech companies did not disclose more than 50% of greenhouse gas emissions along the value chain in their own reports and/or the CDP survey. Instead of the reported 360 megatons carbon dioxide equivalents (the standardized unit for all greenhouse gases), the study arrives at a total of 751 megatons. The 391 megatons discrepancy is comparable to the annual greenhouse gas emissions of Australia.

Significant differences between companies

Half of the companies submitted data to the CDP that did not agree with the data disclosed in their own corporate reports. It was especially common for these reports to ignore GHG Protocol categories that contribute substantially to emissions. For example, 43 percent of the companies neglected emissions from the use of sold products and 30 percent neglected purchased goods and services.

The differences in the quality of companies' disclosures was significant. Whereas some companies omitted only one GHG Protocol category, others ignored all classes of scope 3 emissions. In the biggest discrepancy found by the researchers, the publicly disclosed emissions and the figure calculated differed by a factor of 185. The closest amounts differed by just 0.06%. Hardware companies had omitted more than half of their overall emissions, and software companies somewhat less than half. Companies that have announced ambitious CO2 reduction targets were relatively accurate in their reporting. Here the difference between the disclosed and adjusted quantities was less than 20%.

'Consider adopting binding regulations'

"The often unsystematic and inaccurate reporting of companies' carbon footprints is a problem for policymakers, stakeholders and the companies themselves," says Lena Klaaßen. "The lack of transparency makes it difficult to set realistic targets and develop effective strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the proper assessment of companies." In addition to further research on other branches, the authors believe, that a new regulatory framework is needed. "In light of the current underreporting we have observed, it seems unlikely that voluntary guidelines alone can bring about more accurate disclosures in the future," says Christian Stoll. "Consequently, policy makers should think about binding guidelines with clear rules on how greenhouse gas emissions are reported."Study says tech firms underreport their carbon footprint

More information: Lena Klaaßen et al, Harmonizing corporate carbon footprints, Nature Communications (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-26349-x

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by Technical University Munich