Menendez

Tue, March 22, 2022

Just before the Russian invasion of his country, Ukrainian writer Andrei Kurkov posted a sardonic alert on Twitter: “Kyiv/Kiev weather forecast: +5C, windy, chances of Russian attack 30%, feels like 95%.”

A few days later, he posted a photo of heavily armed soldiers by the side of the road and tagged it “Ukrainian mushroom pickers.” A photo of a bombed building on March 2 was labeled: “A school visit from Putin.”

This kind of ironic, often dark humor defines Ukraine’s culture of resistance, says the Odessa-born poet Ilya Kaminsky.

“In Odessa, it helped people to cope during Soviet times,” Kaminsky wrote in a brief interview I conducted with him over email. “It helped to have a language of its own, with its own jokes and intonations, quotations and echoes not always understood by authorities.”

In a recent interview with Slate, Kaminsky pointed out that the most important holiday in Odessa isn’t Christmas, “It is April 1, April Fool’s Day, which we call Humorina. Thousands of people come to the street and celebrate what they call the day of kind humor. All of Ukraine has a sense of humor — think of the man who offered to tow the Russian tank which had run out of gas back to Russia.

“Humor is part of our resilience,” he said.

War is not funny. Suffering, exile and dispossession are nothing to laugh at. And, yet, humor has always formed part of resistance movements. Why? What role does laughter have to play in times of oppression? Is humor just a safety valve, or can it be the catalyst for real change?

Last year, these questions prompted me to propose a new course at Florida International University. I spent a year developing “Humor as Resistance” as a special topics course in our Writing and Rhetoric track, and this semester, 17 intrepid students enrolled. We were exploring the topic together, when Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine making a hero of the country’s comedian-turned-president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

“I don’t need a ride,” Zelenskyy reportedly told the Americans who wanted to evacuate him in the early days of the invasion. “I need ammunition.”

As the daughter of Cuban exiles, I well understand how humor makes life bearable. Living with despots, sometimes laughter is the only way to tell the truth. One of the first short stories I wrote, “In Cuba I was a German Shepherd,” revolves around a group of old men who tell jokes around the domino table to process the pain of exile. Later, I bonded with my Slovak husband, over jokes that made light of communist-era deprivations:

Man runs into a store. “I’d like a roll of toilet paper.”

Shopkeeper: “We’re out. We’re getting some next week.”

Man: “I can’t wait that long.”

Satire has a long history in the West, of course, going back to at least Aristophanes. But as a form of resistance, it has a particularly strong tradition in Eastern and Central Europe, pre-dating Soviet times. The Odessa-born Isaac Babel was the master of this style during the earlier Russian empire. And, for the Czechs, the great master of ironic resistance was “The Good Soldier Švejk,” the creation of anarchist Jaroslav Hašek, an inveterate hoaxer whose hero, under a cloak of naivete, pierces every cultural pomposity, particular those emanating from the military.

Many of these forms of humor hark back to the literary carnivalesque (embodied by Rabelais and elucidated by the critic Mikhail Bakhtin). The tradition remains alive in Europe, where the spirit infused a range of humorous resistance stunts from the Poles who resisted state propaganda by taking their TV sets out for a walk during the daily newscast to the Otpor movement in Serbia that organized a “birthday celebration” for Milošević complete with cake, card and gifts that included handcuffs and a one-way ticket to the Hague.

With notable exceptions (including Majken Jul Sorensen, whose work has guided my class) most traditional scholarly approaches to humor take a dim view of the power of laughter. Much of the earlier scholarly literature on humorous resistance is preoccupied with the question: “Is it just a way to blow off steam or can humor really change the rules of oppression?”

The question represents a false choice. Resilience is resistance. Beyond instrumentalist aims of humor, laughter is a philosophy, a lightness of life that was most famously captured, in our times, by the writer Milan Kundera who told Philip Roth in an interview: “I could always recognize a person who was not a Stalinist, a person whom I needn’t fear, by the way he smiled. A sense of humor was a trustworthy sign of recognition. Ever since, I have been terrified by a world that is losing its sense of humor.”

I feel for my students. This generation has lived through a civil war in Syria (which has produced more than 5 million refugees) and two years of global pandemic only to now emerge at the cusp of a war that may yet engulf the world. In a broken world, how do we survive?

Violence is its own total vernacular. And we know that a joke has never stopped a bomb. But against the nihilistic darkness of Putin who has suggested “why do we need a world if Russia is not in it?” we can offer the life-affirming light of laughter. We can reject the dour humorlessness of history’s butchers. And we can go on resisting by embracing all the things that make life worth living: friendship, love, and humor, even in the face of extinction.

“Putin died on the 24th of February, 2022 at 5 am Kyiv time,” Kurkov wrote on March 6. “He doesn’t know this yet.”

Ana Menéndez is a writer who teaches at Florida International University. Her most recent novel, “The Apartment,” will be published by Counterpoint Press in April 2023.

Humor As Subversion

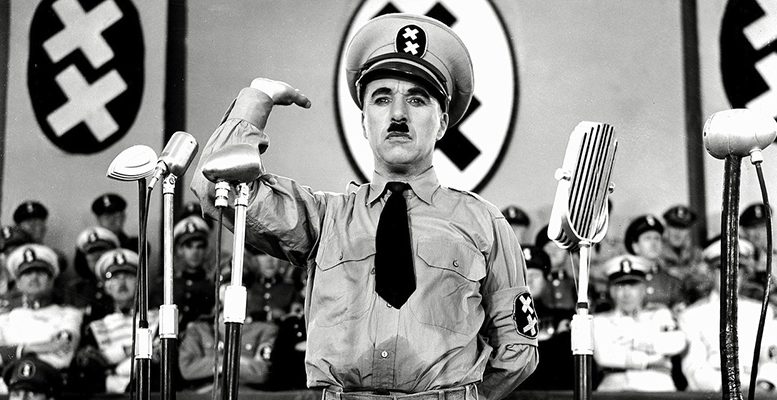

The Great Dictator by Charles Chaplin

The Great Dictator by Charles ChaplinDonato Ndongo-Bidyogo |

George Orwell used to say that “jokes are small revolutions”. What self-respecting autocrat does not have his collection of jokes? Franco, Stalin, Hitler… Simple scape valve of fears and hopes, this modest revenge helps to cope with the absurdity that life can become.

Although jokes never overthrew any tyranny, they act as a cathartic tool, perhaps the only impious transgression that citizens can afford as a form of resistance. Although sometimes they entail risks for those who tell and listen to them.

Ana María Vigara Tauste, linguist at the Complutense University in Madrid who died in 2012, wrote in her study ‘Sex, politics and subversion. The popular joke in the Franco era ‘, that the jokes about Franco and his regime were a “form of humorous rejection of the effective pressure of the dictatorship”.

Sociologist Christie Davies, professor at the University of Reading, who passed away in 2017, compiled in ‘Jokes and Targets’ some of the most celebrated amusing stories in communist Europe. Although it minimized their practical effects – “they did not cause the fall of the Soviet Union,” he said – he considered them fundamental to erode the system, because of their sharp criticism of the political establishment; for him, they predicted the future of socialism better than analysts’ reports, because “they explored all the weaknesses of the system”. According to Davies, a joke is a thermometer and not a thermostat: it indicates what happens, without changing it; at best, it helps maintain morale. Censoring humor, more than a symptom of fear of the powerful, “is a way of saying: here I am, I control the situation!”

Philosopher and political scientist Tomás Várnagy, of the University of Buenos Aires, feels more optimistic about the role of humor against dictators. The examples collected in ‘Proletarians of all countries … Forgive us!’ undermined, in his opinion, the legitimacy of the political, economic and social system they embodied, highlighting the enormous gap between words and reality. He also remembers that, in a democracy, political humor, in its oral or graphic expression, has a very different tone: it serves to laugh at politicians who are not very clever, vain or self-centered, but rarely question the system.