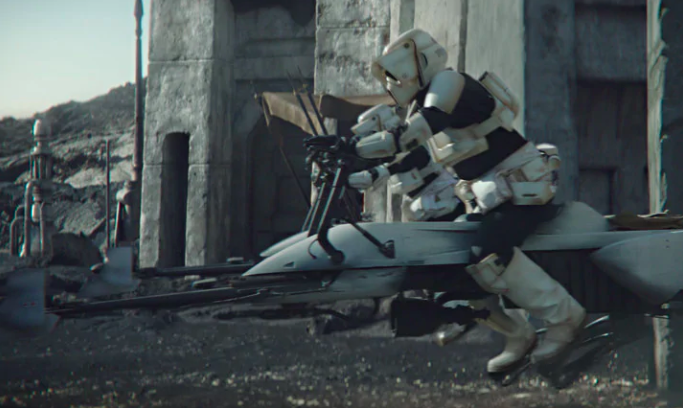

Refugees from Ukraine waiting to disembark at Hungary’s Záhony train station.

BY ERIN O’BRIEN

JACOBIN

04.03.2022

On March 3, a week after Russia invaded Ukraine, Hungarian premier Viktor Orbán traveled to his country’s frontier with Ukraine to meet arriving refugees. In the small border town of Beregsurány, he visited makeshift refugee camps and shook hands with Ukrainians fleeing the war, as well as the Hungarians helping them.

“Nobody will be left uncared for,” Orbán told the gathered journalists.

He praised volunteers’ work and said Hungary would help to both resettle Ukrainian refugees and return home those from “third countries” such as India and Nigeria — whether they wanted to go or not.

Hungary has, up till now, been anything but a haven for refugees. As the leader of the ultraconservative Fidesz party, leading the government since 2010, Orbán has overseen a domestic policy that disparages refugees and migrants, employing racist epithets and stereotypes to justify their exclusion. Orbán and Hungarian authorities have been especially brutal toward the mostly Muslim migrants arriving in the aftermath of wars in Syria and Afghanistan — repeatedly calling them “invaders” and “a poison.”

Just weeks before Orbán shook hands with Ukrainians fleeing war, refugees from Morocco and Afghanistan were illegally beaten and pushed back from the Hungarian-Serbian border while trying to enter Europe via the Balkan route. Orbán has also overseen the construction of a razor-wire fence along that same border — finding much to agree on with Donald Trump and his call for a border wall.

Orbán’s policy on Ukraine might thus be read as a seismic policy shift. However, when analyzed in the context of his former policy and today’s general election, it becomes clear that this is a continuation of his previous racist policy — while also trying to distract from his ties to Vladimir Putin.

Racist Response

As prime minister, Orbán has overseen one of the most brutal and racist responses to Europe’s “refugee crisis.” At the height of the conflict in Syria and Iraq in 2015, refugees came to Europe from those countries in unprecedented numbers. An estimated 1 million people took the Balkan route into Western Europe through Turkey, where most ended up staying. Some continued on dangerous routes to Bulgaria or Greece, and finally into Eastern Europe through countries like Hungary.Just weeks before Orbán shook hands with Ukrainians fleeing war, refugees from Morocco and Afghanistan were illegally beaten and pushed back from the border.

Orbán solidified his rule, and the power of his Fidesz party, through the vilification of these migrants. In 2015, Hungary built a razor-wire fence along its border with Serbia, and images of migrants living in squalid conditions in Hungarian refugee camps circulated widely on social media. Authorities were even filmed throwing food at migrants, as if into a pen.

These real examples of abuse were coupled with equally abusive rhetoric and propaganda. In the lead-up to a referendum on immigration in 2016, posters plastered around Budapest linked migrants to the Paris terror attacks and violence against women. One posted in the capital superimposed a stop sign over an image of a crowd of non-white men and boys.

“Did you know that since the start of the immigration crisis, harassment of women has increased in Europe?” another government poster read.

Also in 2016, his government unilaterally legalized the pushback of refugees — the practice by which police are allowed to physically repel those seeking asylum at the Hungarian border. Pushbacks violate the European Convention of Human Rights, to which Hungary has been a party since 1992.

These practices have continued even as the number of migrants arriving from the Middle East has ebbed, largely as a result of the EU’s deal with Turkey deal to keep migrants in that country, effectively outsourcing border control. This winter, according to reporting by Al Jazeera, migrants were continually pushed back along the Syrian border, with some violently beaten by police.

One Moroccan migrant reportedly had his hands tied behind his back and was forced to the ground and kicked by police in Hungary. Just one week before the war broke out, over one hundred migrants were living in an abandoned milk factory in frigid, squalid conditions near the Serbian-Hungarian border after being denied entrance to Hungary.

A Different Kind of Migrant

However, this war — and the ensuing migrant crisis — is different. Where the influx of mostly Muslim, non-white migrants from the Middle East allowed Orbán to harden his xenophobic, far-right base, Hungary is now facing a war in a bordering country and the arrival of hundreds of thousands of mostly white women and children. Locals are sympathetic, and Ukrainian refugees a cause célèbre.

Orbán has shifted his campaign for the April 3 election to reflect this. Where, in the weeks leading up to the Russian invasion, his central focus was on anti-LGBT sentiment and “traditional values,” with Ukraine and Russia figuring nowhere in his and Fidesz’s platform, the crisis has now come to the fore. Posters plastered around Budapest and campaign rhetoric now present Orbán as a safe choice for Hungarians and a champion for those fleeing the war, whereas the opposition is cast as warmongering.

“The opposition has lost its mind,” Orbán told supporters at an election rally. “They would walk into a cruel, protracted, and bloody war and they want to send Hungarian troops and guns to the front line. We can’t let this happen. Not a single Hungarian can get caught between the Ukrainian anvil and the Russian hammer.”

The explanation for this is partly political — recent polling by International IDEA shows Fidesz still in the lead, but with its 41 percent score only giving it a narrow advantage over the combined opposition of 39 percent. Support for Ukrainians in Hungary is also now widespread, with many civilians and civil society organizations mobilizing to help the influx of refugees. Support for Transcarpathian ethnic Hungarians in Ukraine also gels with Orbán’s nationalist base.

The other explanation is that the acceptance of Ukrainian refugees does not run counter to Orbán’s xenophobic position on migrants. These are, in the main, white, Christian, non-Muslim refugees. Yet Roma refugees, for example, are being subjected to harsh treatment. Speaking at the border on March 3, Orbán claimed he can “tell the difference between who is a migrant and who is a refugee.”

“Migrants are stopped. Refugees can get all the help,” he said, justifying the seeming dissonance in his previous and current stance. Muslim refugees are migrants, in other words; Ukrainian refugees are recognized as such and provided with support. Emphasizing the difference between the two groups enables Orbán to curry public favor while not compromising his hardline stance on Muslim, non-white migrants. The experience of Muslim migrants on the Serbian border confirms this.

Eastern Opening

On March 7, at the train station in the Hungarian border town of Záhony, a railway worker ceremoniously removed a meter-high portrait of Vladimir Lenin from the station and placed it in the back of a pickup truck. Standing before a crowd of reporters, he said that the station no longer had use for the portrait and would use the room concerned for refugees.

Orbán’s shift toward sympathy for Ukrainian refugees has also been a means to distract from his ties to Putin and Russia itself. Orbán first came to the fore of Hungarian politics as a young rebel leader in the late 1980s, famously calling on Soviet troops to leave his country. He rose in popularity as a stanch anti-Soviet, anti-Russian, anti-communist leader who hoped to bring Hungary closer to the West.

In the early years of his career, he emphasized that Hungary’s closest allies were the United States, NATO, and West European countries, while intentionally distancing Hungary, and himself, from Russia and other post-Soviet states. However, over three decades in politics, Orbán has shifted his attitude toward and relationship with Russia.

In 2009, Orbán paid a friendly public visit to Saint Petersburg to meet with Putin and “get to know him” for the first time. Just before he was reelected as premier in 2010, members of Orbán’s inner circle reportedly visited Moscow to strengthen business and political ties between the two countries.

Following his reelection, Orbán displayed a markedly friendlier approach to Russia. Initially, Fidesz dubbed its policy an “eastern opening,” not explicitly mentioning Moscow. However, according to reporting by Hungarian investigative outlet Direkt36, Orbán and his allies saw a closer alliance with Moscow — and Putin — as a way of bettering Fidesz’s standing both domestically and globally.

“Orbán’s power and popularity depend on his relationship with Russia,” said Szabolcs Panyi, an investigative journalist at Direkt36 who has long worked on Orbán’s ties to Russia.

This manifested itself in softer rhetoric towards Moscow and greater animus toward the “West.” Where before, the USSR was the great adversary against which Orbán united his base, he now increasingly accused Brussels of coming for Hungary. “We refused to be dictated by Vienna in 1989 as well,” he said in a speech in 2011. “Nor will we let anyone dictate us from Brussels or from anywhere else.”

The most distinct turning point in Orbán’s stance on Russia came on January 14, 2014, when he announced — from Moscow, accompanied by Putin — that Hungary would acquire a nuclear power plant from Russia with the support of a €10 billion loan from that country, to be paid off over thirty years.

The eight years since then have only seen the further entanglement of Russian and Hungarian business, political, and security interests. Hungary has become a hub for Russian intelligence activity in Europe, and Orbán’s is the only executive in the EU that has not quit International Investment Bank, known as the Russian government’s “trojan horse.”

This relationship has trickled down even to the metro cars purchased by Budapest in 2017. According to reporting by Hungarian outlets, Russian officials were involved in mobilizing against the city’s young transport minister to sideline him and usher through a €200 million deal to buy used Russian railcars. Despite better deals offering more up-to-date technology, the city — under pressure from interests linked to Orbán and his party — purchased the Russian cars for its M3 metro line. They have malfunctioned since being put into operation.

Ties with Putin have also enabled Orbán to ensure low-price energy for households via Russia’s state-owned Gazprom, also helping him inspire a more favorable view toward the Kremlin among his supporters.

Just three weeks before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Putin hosted Orbán in Moscow, where the Hungarian leader requested, among many things, an expansion of his country’s fifteen-year contract with Gazprom amid rising energy prices in Europe.

Orbán and his government maintained this pro-Russia stance as Russian troops massed on Ukraine’s borders this winter and through the first weeks of the war. State-run channels — which investigative journalist Szabolcs Panyi says are essentially propaganda for Orbán’s government — echoed Russian claims, among others, that Russia was clearing Ukraine of Nazis.

However, as public sentiment turned in favor of Ukrainians and the April 3 election neared, Orbán and his followers were forced to fall in line, both with the people of Hungary, who mobilized widespread support for Ukrainian refugees, and with their European counterparts.

Enter a confused government message and position that expressed sympathy with refugees while failing to condemn Russia or cut ties with Putin’s inner circle. As of mid-March, Panyi said, the government hadn’t figured out its messaging.

“I think that the Hungarian government still hasn’t found its message and how to relate to this conflict,” Panyi said. “For example, when the invasion started on Thursday and Friday, Orbán gave an interview. He talked for about thirty minutes about the conflict, but he did not mention Russia or Vladimir Putin.”

Certainly, the government’s actions run counter to its supposed pro-Ukrainian migrant stance. As European allies have taken steps to sever energy and economic ties to Russia, Hungary has demurred. After speaking about the importance of Ukraine’s “territorial integrity” following the Russian invasion, Orbán said on March 3 that his country would not veto EU sanctions on Russia. The integrity of the EU was paramount, he said. However, last week Hungary rejected sanctions on Russian energy shipments, saying it would “endanger Hungary’s energy security.” Such sanctions would also directly threaten Orbán’s low-cost utility scheme, central to his bid to stay in power after today’s election. Hungary is also not supplying arms to Ukraine or allowing the transit of weapons to the country through its territory.

Politicians in Poland and the Czech Republic have sharply criticized Orbán’s failure to cut ties with Russia over the war in Ukraine and for his comparatively muted refugee response. “The Hungarians must be punished for their pro-Russian stance,” tweeted Krzysztof Gawkowski, leader of the parliamentary group for Poland’s left-wing party Lewica. These comments came as Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia each declined invitations to a Budapest summit to discuss Hungary’s position. The Czech defense minister even accused Hungarian politicians of finding “cheap Russian oil more important than Ukrainian blood.”

Welcome for Some

Orbán’s tempered stance toward Russia suggests that his attitude towards Ukrainian refugees is a rhetorical shift — seeking to curry favor and votes in the lead-up to today’s election, which is more contested than usual. But the hollowness of his new “pro-refugee” stance is also echoed in the experience of citizens of African countries fleeing Ukraine and now stuck in Záhony.

When I was in this town on Hungary’s border with Ukraine on March 7, I spoke to a young doctor from Zimbabwe named Chennai. She had been at the Hungarian Reformed Church reception center for several days and looked at me with surprise when I asked her what her plan was.

“I have no plan,” she said, “Maybe I will go to America.”

She and her boyfriend had been told by Hungarian authorities that they could be resettled back to Zimbabwe, but were not given work or resettlement options in the country. When we met in the school-turned-refugee-center, she said she was waiting for a bus — any bus — to Europe. She’d heard that there were shortages of medical staff there and in the United States, and thought she might be able to find work.

Where Ukrainian people were immediately offered aid and work opportunities in the country, she and her partner were offered little. The only people left at the reception center when we spoke were Chennai, her boyfriend, and several Nigerian refugees who, like Chennai, had fled Kharkiv. None of them wanted to go home, but none knew where else they could go — and they certainly did not intend to stay in Hungary.

Orbán’s shift and the welcoming of Ukrainian refugees have not forced him to shift his racist stance toward non-white refugees, nor cut any of his long-standing ties with Putin. In other words, he’s playing the welcoming host while remaining a beneficiary of Russia’s energy and security infrastructure. If, as many observers are already doubting, today’s elections are fair, they will show whether his ruse has worked.

With thanks to Flora Garamvolgyi for her help with reporting.

Erin O’Brien is a freelance journalist based in Istanbul, Turkey, covering politics and culture.