Americans’ support for LGBTQ rights higher than ever, even as white evangelicals lag

While Republicans and white evangelical Protestants are among the least likely to support three key policies regarding LGBTQ rights, their support still has increased overall in the past seven years.

(RNS) — Americans’ support for LGBTQ rights is higher than ever, according to a new report by Public Religion Research Institute, though two groups have “consistently lagged” in their support for key policies: Republicans and white evangelical Protestants.

Those findings, released Thursday (March 17), are part of PRRI’s 2021 American Values Atlas project, a seven-year survey measuring Americans’ support for LGBTQ rights policies.

The report comes as a number of states are considering legislation related to LGBTQ issues and as questions of whether one can refuse service to LGBTQ people based on religious beliefs are likely to come before the U.S. Supreme Court in the next year. Currently, few states have nondiscrimination protections in place for LGBTQ people.

Meanwhile, Christian denominations such as the United Methodist Church and the Reformed Church in America are splintering around marrying and ordaining LGBTQ people.

“This massive 50-state study brings into sharp focus the contradiction between increasing support for LGBTQ rights, including rights for transgender Americans, and the proliferation of laws seeking to restrict or abolish those rights over the last year,” PRRI founder and CEO Robert P. Jones said in a written statement.

“Support for nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ Americans has never been higher and garners the support of all political parties and major religious groups.”

RELATED: Record numbers of Americans identify as LGBTQ. What does that mean for Christianity? (COMMENTARY)

Since 2014, PRRI — a Washington, D.C.-based research firm focused on the intersection of religion, values and public life — has been asking American adults whether they support allowing lesbian and gay couples to marry legally.

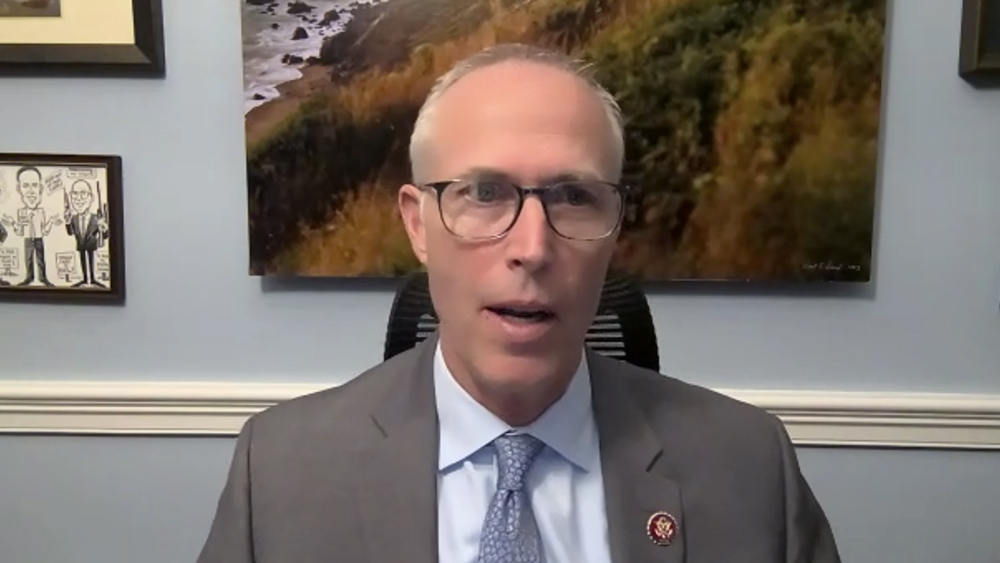

Natalie Jackson. Photo courtesy of PRRI

Since 2015, the firm has also been asking Americans whether they support laws to protect lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people against discrimination in jobs, public accommodations and housing, as well as whether they support allowing small-business owners to refuse to provide products or services to lesbian or gay people if doing so would violate their religious beliefs.

“It remains critical to show that Americans are very broadly supportive of LGBTQ rights, especially in an environment where some of that is still subject to question and even being questioned more in the past couple of years than maybe it was five years ago,” Natalie Jackson, PRRI’s director of research, told Religion News Service.

Jackson pointed to recent moves by politicians in Texas and Florida. Gov. Greg Abbott recently directed the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services to investigate medical treatments for transgender adolescents as child abuse. Florida lawmakers passed what critics are calling the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, which would restrict discussions about LGBTQ people in public schools.

Other states are considering similar legislation.

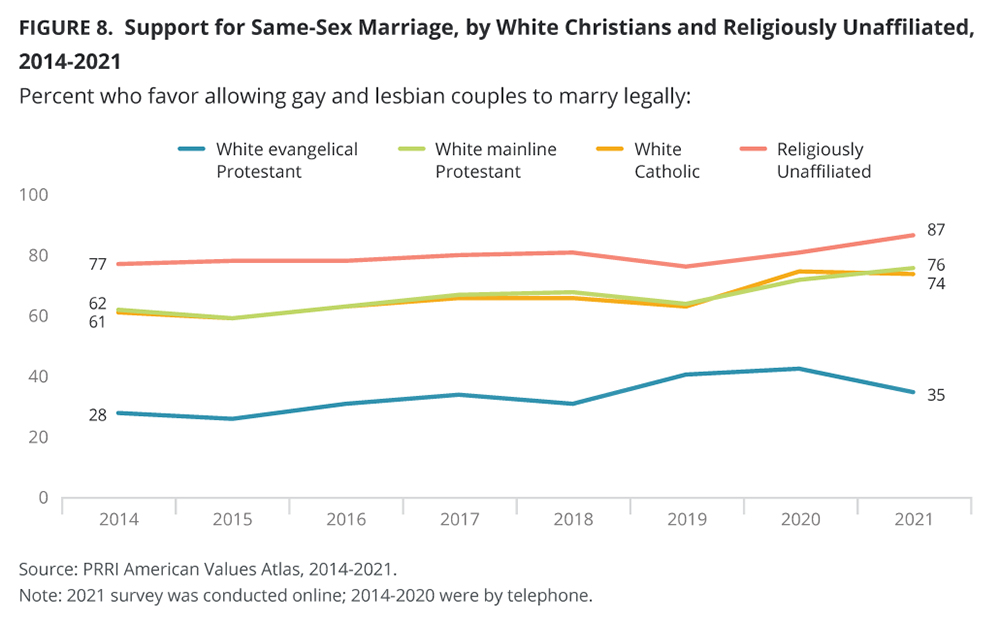

Since PRRI began polling on the issue, the number of Americans who support same-sex marriage has increased among all political and religious groups from 54% to 68%, according to the report.

“Support for Same-Sex Marriage, by White Christians and Religiously Unaffiliated, 2014-2021” Graphic courtesy of PRRI

That includes 87% of those who describe themselves as religiously unaffiliated (up from 77% in 2014); 76% of white mainline Protestants (up from 62%); and 74% of white Catholics (up from 61%). Trailing behind are 35% of white evangelical Protestants (still up overall from 28%).

However, while numbers have increased from 2014 overall, in the last year that support has taken a dip among white Catholics and evangelicals, though Jackson said the change in white Catholics is not statistically significant and she wouldn’t read too much into it unless it continued.

White evangelical support dropped from 43% to 35%, which Jackson called a “pretty solid downturn.”

“It’s just highlighting that even among white Christians, white evangelicals are a significant outlier,” she said.

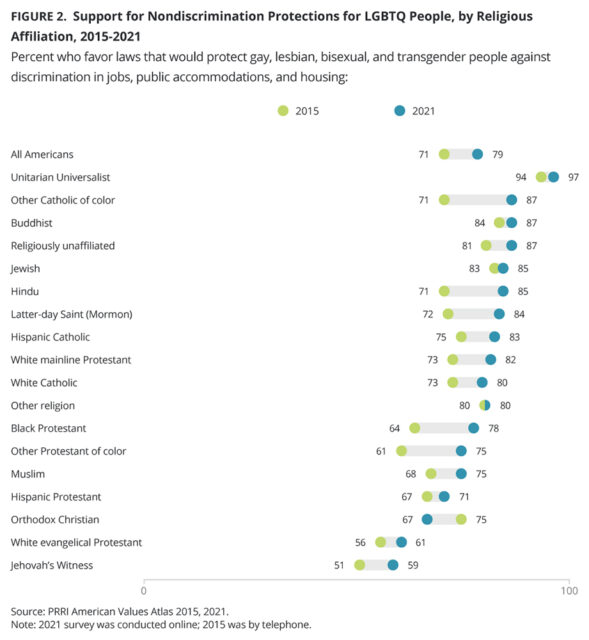

Most Americans (79%) also support discrimination protections for LGBTQ people. That number has increased from 71% in 2015.

“Support for Nondiscrimination Protections for LGBTQ People, by Religious Affiliation, 2015-2021” Graphic courtesy of PRRI

That support is nearly universal among Unitarian Universalists (97%), although the report did not note how many Unitarian Universalists were surveyed. It is also high (87%) among the religiously unaffiliated, Catholics who are not white or Hispanic, and Buddhists. (The report also did not note how many Buddhists had been surveyed, though Jackson said no subgroup had fewer than 80 people.)

On the other end of the spectrum are 59% of Jehovah’s Witnesses, 61% of white evangelical Protestants and 71% of Hispanic Protestants. (The report did not note how many Jehovah’s Witnesses had been surveyed.)

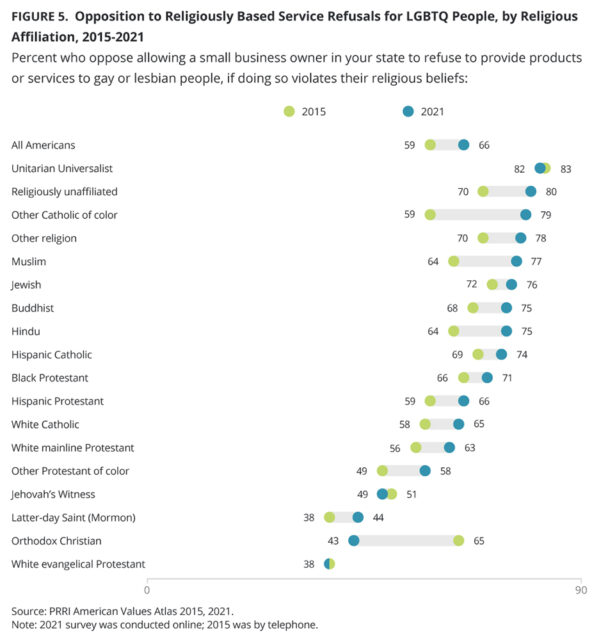

Nearly two-thirds of Americans (66%) also oppose religiously based refusals to serve gay and lesbian people — a number that has fluctuated while trending upward from 59% since 2015.

“Opposition to Religiously Based Service Refusals for LGBTQ People, by Religious Affiliation, 2015-2021” Graphic courtesy of PRRI

The number of people who oppose allowing a small-business owner in their states to refuse service to gay or lesbian people because of religious beliefs is highest again among Unitarian Universalists (83%), the religiously unaffiliated (80%) and Catholics who are not white or Hispanic (79%).

Opposition is lowest among white evangelical Protestants (38%, a number that has not changed since 2015) and Latter-day Saints (44%).

While Republicans and white evangelical Protestants are among the least likely to support these policies regarding LGBTQ rights, the report noted, their numbers still have increased overall on most questions in the past seven years and strong majorities support nondiscrimination policies.

White evangelicals are a small part of the U.S. population, Jackson noted, but they are dependable voters. And evangelical leaders have had close ties to politics and politicians for decades, she added.

“White evangelicals are about 14% of the population overall, which is certainly not what you would think by the amount of focus that they get, the amount of leverage that they seem to have,” she said.

RELATED: Texas faith groups mobilize against governor’s order to probe child trans treatments

PRRI surveyed 22,612 adults ages 18 and up living in all 50 states in four waves during 2021. The margin of error is +/- 0.8 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence.

.png)