The danger here is that the emergent political dimensions will undermine the prospects of economic recovery.

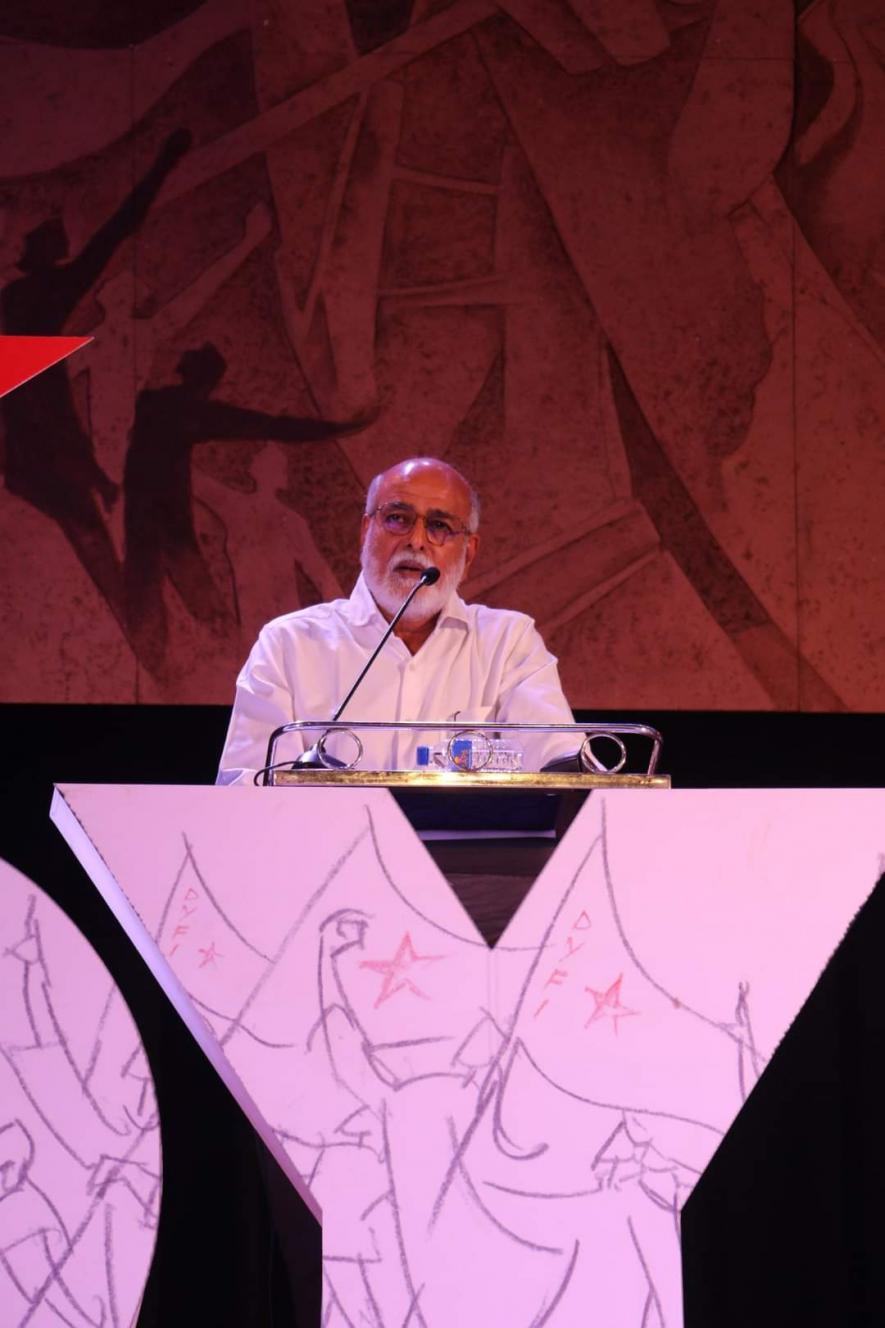

M.K. Bhadrakumar

16 May 2022

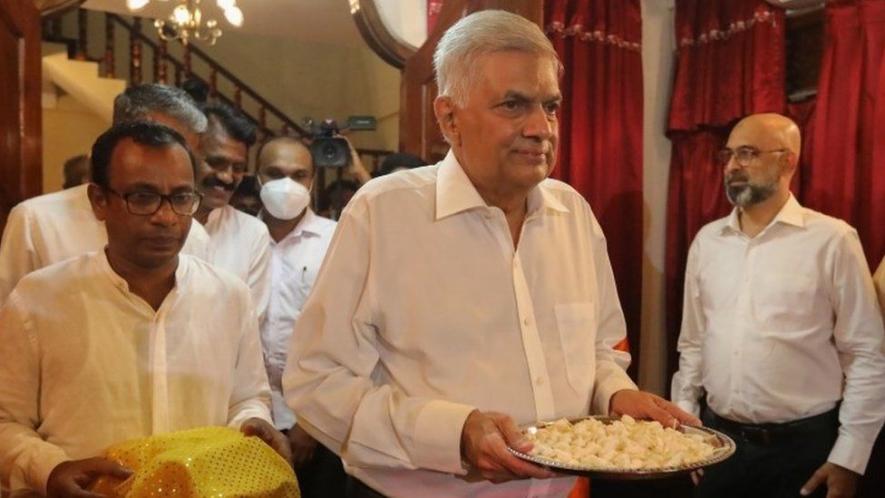

Ranil Wickremesinghe arrives at a Buddhist temple after his latest appointment as prime minister, Colombo, May 13, 2022.

India finds itself between the rock and a hard place in its approach to the Sri Lankan crisis. There is no question that the government attributes primacy to Sri Lanka remaining a practising democracy. But the developing situation in that country is going to be a cliffhanger right up to the final whistle.

Things can take different turns. The best hope is that although the political class is thoroughly discredited and the legislative is dysfunctional, the democratic spirit lingers on. Arguably, the protests themselves are a manifestation of it — an inchoate uprising clamouring for political accountability by the elected government. The democratic foundations of the state are not irreparably damaged.

Political transition has become the core demand of the protestors and embedded within that the non-negotiable pre-condition that President Gotabaya Rajapaksa should quit office. The demand has been partially conceded, although with caveats, but the pre-condition on the president’s ouster hangs in the air. No one knows how to bell the cat.

Rajapaksa acted smartly by appointing as interim prime minister a senior politician with sound experience, Ranil Wickremesinghe, but the fact remains that the latter is in popular perception someone who is close to the president’s family, and whom the president can rely upon to protect the family’s security and interests if the crunch time comes. Simply put, it is old wine in a new bottle.

On the plus side, however, this is the sixth time that Wickremesinghe is holding the post of prime minister and he enjoys acceptability in Delhi and the western capitals as a sober thinker and doer who can be trusted to steer clear of rash decisions, which is useful at the present juncture to source urgently needed help from abroad to navigate the crisis in the Sri Lankan economy.

On the other hand, Wickremesinghe is a discredited politician himself who never once completed a term in office as prime minister, and he represents a one-man party (himself) in the parliament and is a spent force politically. As the Archbishop of Colombo Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith put it, “People want a person with integrity, not someone who has been defeated in politics.”

There is lurking suspicion In Colombo that Rajapaksa picked Wickremesinghe primarily to deflect the protestors’ demand for his own exit. The BBC reported that the news of Wickremesinghe’s appointment has been “largely met with dismay and disbelief” in Sri Lanka.

This becomes important in the days and weeks ahead because the onerous responsibility to steer the political transition to calmer waters leading to fresh elections and the formation of a new government, etc. falls on Wickremesinghe’s shoulders. The big question is: Will he persuade Rajapaksa to step down?

The high probability is that Rajapaksa may instead try to use Wickremesinghe as a firewall to weather the protests, in effect, to defy the protestors’ demand that he quit. Suffice to say, the future of the Wickremesinghe government is murky at best.

The danger here is that the emergent political dimensions will undermine the prospects of economic recovery. It is going to be next to impossible for Wickremesinghe to negotiate the bridging finance and the agreement with the IMF while simultaneously on a parallel track clip the powers of the executive presidency and set a date for Rajapaksa to resign and for the office of the executive presidency to be abolished. The economic agenda itself is so daunting.

In addition to negotiating with the IMF on the details of long-term structural reforms, the government will need to arrange urgent “bridge financing” from international agencies to inject short-term liquidity, convince creditors to allow a pause in debt payments, and prepare a range of legislation to increase taxes and cut non-urgent public spending.

Without doubt, the IMF has already spelt out the reforms needed to win its financial support, which include a long series of austerity measures, from budget cuts to income tax and VAT increases, an end to inflationary money printing by the Central Bank, phasing out import restrictions, stopping government interventions aimed at stabilising the rupee, and “growth-enhancing structural reforms”, including unpopular measures such as the sale or partial privatisation of state-owned companies, removal of costly social subsidies, and so on.

As for Rajapaksa, he seems determined to cling to power, especially in the face of the public calls to hold him and his family accountable for alleged corruption and other crimes. He has expressed no intention to resign his post and instead has floated the idea vaguely of curtailing his executive powers. The situation is extremely volatile. Even deeper economic collapse or more serious social unrest becomes a possibility if the political standoff continues unresolved quickly.

At any rate, the process to remove or sideline President Rajapaksa is likely to take weeks, if not months, and could fail entirely. This is where Rajapaksa may seize the moment to turn the turmoil to his own purpose by resorting to violent repression (consistent with his past record) or bring in the military for a larger role in governance.

The top military commanders – most notably the army chief, Major General Shavendra Silva and the defence secretary, retired General Kamal Gunaratne — are known to be close to the president. The military personnel live a life of perks and privileges in Sri Lanka and as stakeholders, they would have no qualms about turning their guns on protestors to preserve the regime.

Of course, the role of the international community is relevant but it is not to be exaggerated. The military leadership is unlikely to be deterred from intervening in politics or from brutal suppression of protests in support of the regime. Interestingly, the incumbent army chief is already under US sanctions for alleged war crimes (committed under Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s watch as the defence secretary during the civil war.)

Paradoxically, any lifeline from the IMF, while easing economic hardships for the average Sri Lankans and lessen the intensity of the clamour for political change, could also provide breathing space to Rajapaksa, allowing him and his family to restore themselves. The family has a history of rising like the Phoenix from the ashes.

Sri Lanka is only one of some 35 developing countries today that are struggling with post-pandemic economic recovery. The big powers have little time left for Sri Lanka amidst the birth pangs of a multipolar world order. Therefore, the chances are that Gotabaya Rajapaksa, a ruthless practitioner of power, will strive to attrition the protesters somehow to survive the challenge to his leadership.