Walking gives the brain a ‘step-up’ in function for some

It has long been thought that when walking is combined with a task – both suffer. Researchers at the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience at the University of Rochester found that this is not always the case. Some young and healthy people improve performance on cognitive tasks while walking by changing the use of neural resources. However, this does not necessarily mean you should work on a big assignment while walking off that cake from the night before.

“There was no predictor of who would fall into which category before we tested them, we initially thought that everyone would respond similarly,” said Eleni Patelaki, a biomedical engineering Ph.D. student at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry in the Frederick J. and Marion A. Schindler Cognitive Neurophysiology Laboratory and first author of the study out now in Cerebral Cortex. “It was surprising that for some of the subjects it was easier for them to do dual-tasking – do more than one task – compared to single-tasking – doing each task separately. This was interesting and unexpected because most studies in the field show that the more tasks that we have to do concurrently the lower our performance gets.”

Improving means changes in the brain

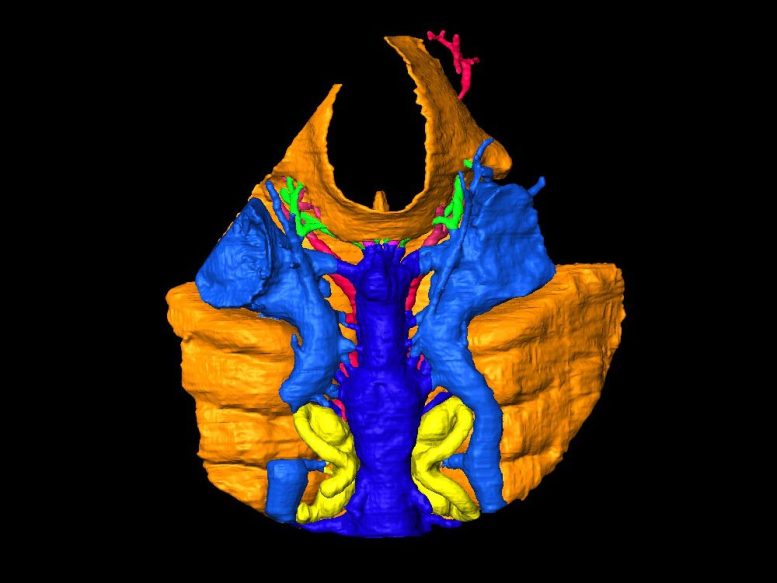

Using the Mobile Brain/Body Imaging system, or MoBI, researchers monitored the brain activity, kinematics and behavior of 26 healthy 18 to 30-year-olds as they looked at a series of images, either while sitting on a chair or walking on a treadmill. Participants were instructed to click a button each time the image changed. If the same image appeared back-to-back participants were asked to not click.

Performance achieved by each participant in this task while sitting was considered their personal behavioral “baseline”. When walking was added to performing the same task, investigators found that different behaviors appeared, with some people performing worse than their sitting baseline - as expected based on previous studies - but also with some others improving compared to their sitting baseline. The electroencephalogram, or EEG, data showed that the 14 participants who improved at the task while walking had a change in frontal brain function which was absent in the 12 participants who did not improve. This brain activity change exhibited by those who improved at the task suggests increased flexibility or efficiency in the brain.

“To the naked eye, there were no differences in our participants. It wasn’t until we started analyzing their behavior and brain activity that we found the surprising difference in the group's neural signature and what makes them handle complex dual-tasking processes differently,” Patelaki said. “These findings have the potential to be expanded and translated to populations where we know that flexibility of neural resources gets compromised.”

Edward Freedman, Ph.D., associate professor of Neuroscience at the Del Monte Institute led this research that continues to expand how the MoBI is helping neuroscientists discover the mechanisms at work when the brain takes on multiple tasks. His previous work has highlighted the flexibility of a healthy brain, showing the more difficult the task the greater the neurophysiological difference between walking and sitting. “These new findings highlight that the MoBI can show us how the brain responds to walking and how the brain responds to the task,” Freedman said. “This gives us a place to start looking in the brains of older adults, especially healthy ones.”

Impact on aging

Expanding this research to older adults could guide scientists to identify a possible marker for ‘super agers’ or people who have a minimal decline in cognitive functions. This marker would be useful in helping better understand what could be going awry in neurodegenerative diseases.

Additional authors include John Foxe, Ph.D., and Kevin Mazurek, Ph.D., of the University of Rochester Medical Center. This research was supported by the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience Pilot Program, the University of Rochester CTSA award number KL2 TR001999 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institutes of Health. Recordings were conducted at the University of Rochester Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (UR-IDDRC).

JOURNAL

Cerebral Cortex