Infected herbivores eat less, allowing plants to flourish

A caribou on Siberia’s Yamal Peninsula browses on some willows.

JEFF KERBY

By Jake Buehler

Gut parasites in large plant eaters like caribou thrive out of sight and somewhat out of mind. But these tiny tummy tenants can have big impacts on the landscape that their hosts travel through.

Digestive tract parasites in caribou can reduce the amount that their hosts eat, allowing for more plant growth in the tundra where the animals live, researchers report in the May 17 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The finding reveals that even nonlethal infections can have reverberating effects through ecosystems.

Interactions between species have long been known to ripple through ecosystems, indirectly impacting other parts of the food web. When predators eat herbivores, for example, a reduction in plant-eating mouths leads to changes in the plant community. This is how sea otters, for example, can encourage kelp growth by feeding on herbivorous urchins (SN: 3/29/21).

“Anytime you have a change in species interactions that changes what the animals are doing on the landscape, it can influence their impact on the ecosystem,” says Amanda Koltz, an ecologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

When parasites and pathogens kill their hosts, it can have a similar effect to predators on ecosystems. A prime example is the rinderpest virus, which in the late 19th century devastated populations of ruminants — buffalo, antelope, cattle — in sub-Saharan Africa. Once wildebeest populations in East Africa were spared further infection following the vaccination of cattle and the eradication of the virus, their exploding numbers trimmed the grass back in the Serengeti and led to other landscape changes.

But unlike rinderpest, most infections aren’t lethal. Nonlethal parasite infections are pervasive in ruminants — plant eaters that play key roles in shaping vegetation on land. Koltz and her team wondered if changes to a ruminant’s overall health or behavior from a chronic parasitic infection could also induce changes in the surrounding plant community.

By Jake Buehler

Gut parasites in large plant eaters like caribou thrive out of sight and somewhat out of mind. But these tiny tummy tenants can have big impacts on the landscape that their hosts travel through.

Digestive tract parasites in caribou can reduce the amount that their hosts eat, allowing for more plant growth in the tundra where the animals live, researchers report in the May 17 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The finding reveals that even nonlethal infections can have reverberating effects through ecosystems.

Interactions between species have long been known to ripple through ecosystems, indirectly impacting other parts of the food web. When predators eat herbivores, for example, a reduction in plant-eating mouths leads to changes in the plant community. This is how sea otters, for example, can encourage kelp growth by feeding on herbivorous urchins (SN: 3/29/21).

“Anytime you have a change in species interactions that changes what the animals are doing on the landscape, it can influence their impact on the ecosystem,” says Amanda Koltz, an ecologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

When parasites and pathogens kill their hosts, it can have a similar effect to predators on ecosystems. A prime example is the rinderpest virus, which in the late 19th century devastated populations of ruminants — buffalo, antelope, cattle — in sub-Saharan Africa. Once wildebeest populations in East Africa were spared further infection following the vaccination of cattle and the eradication of the virus, their exploding numbers trimmed the grass back in the Serengeti and led to other landscape changes.

But unlike rinderpest, most infections aren’t lethal. Nonlethal parasite infections are pervasive in ruminants — plant eaters that play key roles in shaping vegetation on land. Koltz and her team wondered if changes to a ruminant’s overall health or behavior from a chronic parasitic infection could also induce changes in the surrounding plant community.

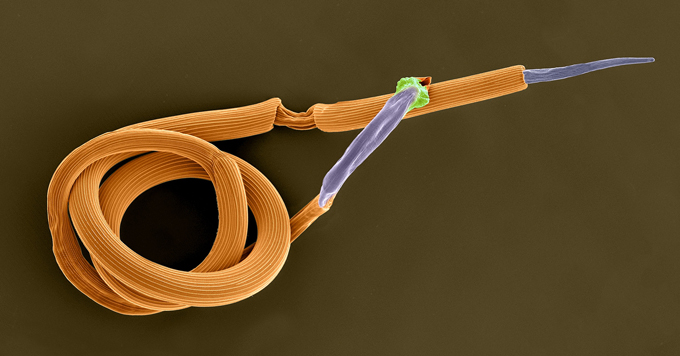

Parasites like this brown stomach worm (Teladorsagia circumcincta), shown in an SEM image, are common residents of the guts of ruminants such as sheep, cattle and deer.

DENNIS KUNKEL MICROSCOPY/SCIENCE SOURCE

The researchers looked to caribou (Rangifer tarandus). Using data from published studies, Koltz and her team developed a series of mathematical simulations to test how caribou survival, reproduction and feeding rate could be influenced by stomach worm (Ostertagia spp.) infections.

The scientists then calculated how these effects could alter the total mass of and population changes in the caribou, parasites and plants. The simulations predict that not only could lethal infections trigger a cascade leading to more plant mass, but also nonlethal infections had just as large an effect. Sickened caribou that ate less or experienced a drop in reproduction rate led to an increase in plant mass when compared with a scenario with no parasites.

The team also analyzed data from 59 studies on 18 species of ruminants and their parasites, gathering information on how the parasites impact host feeding rates and body mass. The analysis found that chronic parasitic infections generally cause many types of herbivores to eat less, also reducing their body mass and fat reserves.

Indirect ecological ramifications from parasitic infections could be common in ruminants all over the world, the researchers conclude.

The study “highlights that there are widespread interactions that we’re not considering in ecosystem contexts quite yet, but we should be,” Koltz says.

Globally, parasites face an uncertain future with fast environmental changes — like climate change and habitat loss from changes in land use — altering relationships with their hosts, potentially leading to many parasite extinctions. “How such changes in host-parasite interactions might disrupt the structure and functioning of ecosystems is a topic that we should be thinking about,” Koltz says.

The findings also are “going to change how we think about what controls ecosystems,” says Oswald Schmitz, a population ecologist at Yale University who was not involved in the research. “Maybe it isn’t predators that are necessarily controlling the ecosystem, maybe the parasites are more important,” he says. “And so, what we really need to do is more research that disentangles [this].”

Scientists are rapidly gaining a better understanding of parasites’ ubiquity and abundance, says Joshua Grinath, an ecologist at Idaho State University in Pocatello. “Now we are challenged with understanding the roles of parasites within ecological communities and ecosystems.”

sciencenews.org

CITATIONS

A.M. Koltz et al. Sublethal effects of parasitism on ruminants can have cascading consequences for ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 119, May 17, 2022, e2117381119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2117381119.

R.M. Holdo et al. A disease-mediated trophic cascade in the Serengeti and its implications for ecosystem C. PLOS Biology. Published September 29, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000210.

C.J. Carlson et al. Parasite biodiversity faces extinction and redistribution in a changing climate. Science Advances. Vol. 3., September 6, 2017. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602422.

About Jake Buehler

The researchers looked to caribou (Rangifer tarandus). Using data from published studies, Koltz and her team developed a series of mathematical simulations to test how caribou survival, reproduction and feeding rate could be influenced by stomach worm (Ostertagia spp.) infections.

The scientists then calculated how these effects could alter the total mass of and population changes in the caribou, parasites and plants. The simulations predict that not only could lethal infections trigger a cascade leading to more plant mass, but also nonlethal infections had just as large an effect. Sickened caribou that ate less or experienced a drop in reproduction rate led to an increase in plant mass when compared with a scenario with no parasites.

The team also analyzed data from 59 studies on 18 species of ruminants and their parasites, gathering information on how the parasites impact host feeding rates and body mass. The analysis found that chronic parasitic infections generally cause many types of herbivores to eat less, also reducing their body mass and fat reserves.

Indirect ecological ramifications from parasitic infections could be common in ruminants all over the world, the researchers conclude.

The study “highlights that there are widespread interactions that we’re not considering in ecosystem contexts quite yet, but we should be,” Koltz says.

Globally, parasites face an uncertain future with fast environmental changes — like climate change and habitat loss from changes in land use — altering relationships with their hosts, potentially leading to many parasite extinctions. “How such changes in host-parasite interactions might disrupt the structure and functioning of ecosystems is a topic that we should be thinking about,” Koltz says.

The findings also are “going to change how we think about what controls ecosystems,” says Oswald Schmitz, a population ecologist at Yale University who was not involved in the research. “Maybe it isn’t predators that are necessarily controlling the ecosystem, maybe the parasites are more important,” he says. “And so, what we really need to do is more research that disentangles [this].”

Scientists are rapidly gaining a better understanding of parasites’ ubiquity and abundance, says Joshua Grinath, an ecologist at Idaho State University in Pocatello. “Now we are challenged with understanding the roles of parasites within ecological communities and ecosystems.”

sciencenews.org

CITATIONS

A.M. Koltz et al. Sublethal effects of parasitism on ruminants can have cascading consequences for ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 119, May 17, 2022, e2117381119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2117381119.

R.M. Holdo et al. A disease-mediated trophic cascade in the Serengeti and its implications for ecosystem C. PLOS Biology. Published September 29, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000210.

C.J. Carlson et al. Parasite biodiversity faces extinction and redistribution in a changing climate. Science Advances. Vol. 3., September 6, 2017. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602422.

About Jake Buehler

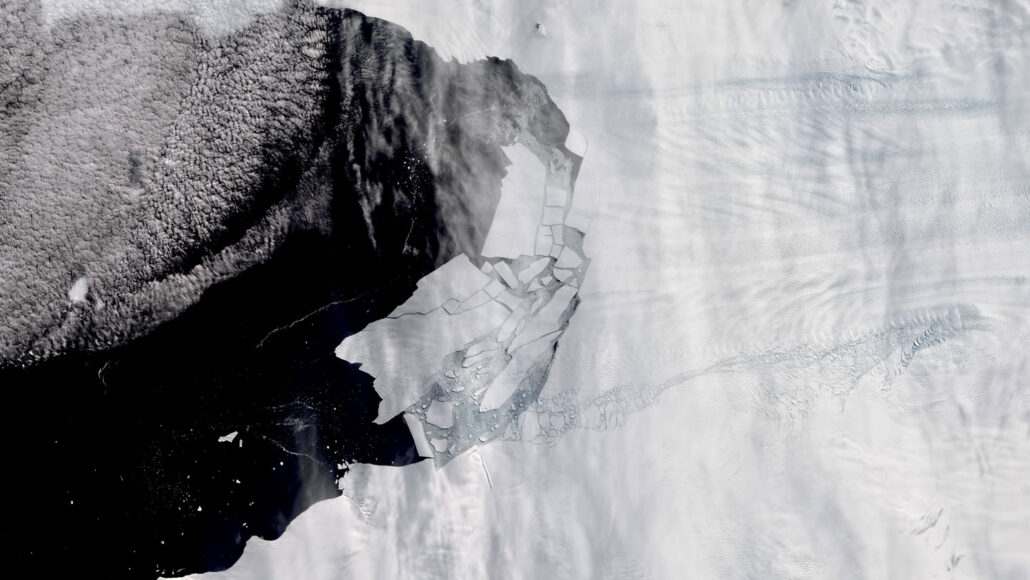

Researchers dated ancient shorelines (seen here as the series of small ridges in the rocky terrain between the foreground boulders and background snow) on islands roughly 100 kilometers from Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers in Antarctica to help figure out if the glaciers are in the process of unstable, runaway retreat.

Researchers dated ancient shorelines (seen here as the series of small ridges in the rocky terrain between the foreground boulders and background snow) on islands roughly 100 kilometers from Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers in Antarctica to help figure out if the glaciers are in the process of unstable, runaway retreat.