By AFP News

08/11/22

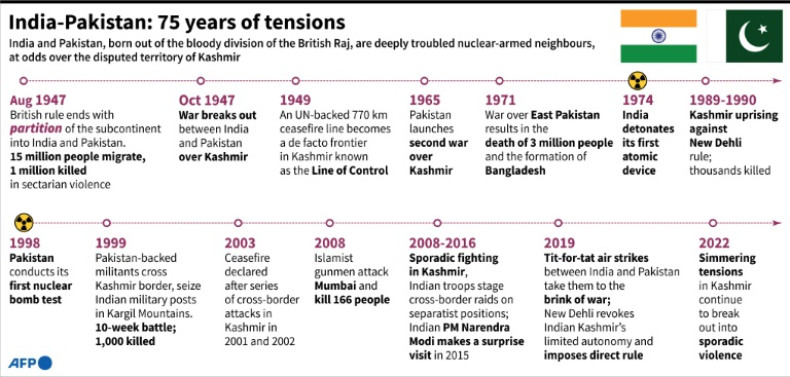

India and Pakistan, born 75 years ago out of the bloody division of the British Raj, are deeply troubled neighbours, at odds over the disputed territory of Kashmir.

Here are key dates in the fraught relations of the nuclear-armed rivals:

Overnight on August 14-15, 1947, Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India, brings the curtain down on two centuries of British rule. The Indian sub-continent is divided into mainly Hindu India and Muslim-majority Pakistan.

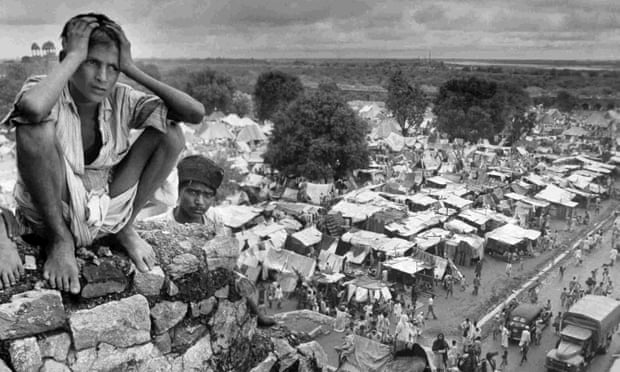

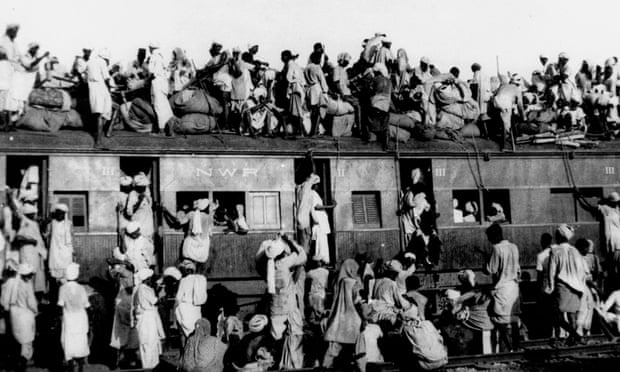

A poorly prepared partition throws life into disarray, displacing some 15 million and unleashing sectarian bloodshed that kills possibly more than a million people.

Late in 1947, war breaks out between the two neighbours over Kashmir, a Muslim-majority region in the Himalayas.

A UN-backed, 770-kilometre (478-mile) ceasefire line in January 1949 becomes a de facto frontier dividing the territory, now known as the Line of Control and heavily militarised on both sides.

Some 37 percent of the territory is administered by Pakistan and 63 percent by India, with both claiming it in full.

Pakistan launches a war in August-September 1965 against India for control of Kashmir. It ends inconclusively seven weeks later after a ceasefire brokered by the Soviet Union.

The neighbours fight a third war in 1971, over Islamabad's rule in then East Pakistan, with New Delhi supporting Bengali nationalists seeking independence for what would in March 1971 become Bangladesh. Three million people die in the short war.

India detonates its first atomic device in 1974, while Pakistan's first public test will not come until May 1998. India carries out five tests that year and Pakistan six. Respectively the world's sixth and seventh nuclear powers, they stoke global concern and sanctions.

An uprising breaks out in Kashmir against New Delhi's rule in 1989, and thousands of fighters and civilians are killed in the following years as battles between security forces and Kashmiri militants roil the region.

Widespread human rights abuses are documented on both sides of the conflict as the insurgency takes hold.

Thousands of Kashmiri Hindus flee to other parts of India from 1990 fearing reprisal attacks.

In 1999, Pakistan-backed militants cross the disputed Kashmir border, seizing Indian military posts in the icy heights of the Kargil mountains. Indian troops push the intruders back, ending the 10-week conflict, which costs 1,000 lives on both sides.

The battle ends under pressure from the United States.

A series of attacks in 2001 and 2002, which India blames on Pakistani militants, leads to a new mobilisation of troops on both sides.

A ceasefire is declared along the frontier in 2003, but a peace process launched the following year ends inconclusively.

In November 2008, Islamist gunmen attack the Indian city of Mumbai and kill 166 people. India blames Pakistan's intelligence service for the assault and suspends peace talks.

Contacts resume in 2011, but the situation is marred by sporadic fighting.

Indian troops stage cross-border raids in Kashmir against separatist positions.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi makes a surprise visit in December 2015 to Pakistan.

India vows retaliation after 41 paramilitary members are killed in a 2019 suicide attack in Kashmir claimed by a Pakistan-based militant group.

Tit-for-tat air strikes between the two nations take them to the brink of war.

Later that year, India suddenly revokes Kashmir's limited autonomy under the constitution, detaining thousands of political opponents in the territory.

Authorities impose what becomes the world's longest internet shutdown and troops are sent to reinforce the estimated half a million security forces already stationed there.

Tens of thousands of people, mainly civilians, have been killed since 1990 in the insurgency.

Rosemary Wardley - Tuesday- NAT GEO

With the end of British colonial rule in 1947, the Indian subcontinent was divided into two nations, majority-Hindu India and majority-Muslim Pakistan.

© Provided by National Geographic75 years after Partition: These maps show how the British split India

But simmering secular tensions and a hastily planned transition—overseen by a team without any expertise in mapmaking or Indian culture—led to one of the largest refugee crises in history. It also prompted a wave of brutalities that would leave lasting scars for the people living in the two new sovereign nations.

(Why the Partition of India and Pakistan still casts a long shadow over the region.)

Confusion over the new border—and rising tensions among those who suddenly found their minority and majority statuses switched—was like a spark to a flame. Violence broke out across the subcontinent, particularly in Punjab and Bengal.

Although the violence faded by 1950, the Radcliffe Line has still had lasting implications for the region. In 1971, the people of East Pakistan declared independence for the new nation of Bangladesh. And the southern border of Jammu and Kashmir, a princely state that chose to remain independent after Partition, is still contested today.

© Provided by National Geographic75 years after Partition: These maps show how the British split India

(See maps of India and Pakistan’s conflict over mountains and glaciers)

Abhaya Srivastava with Zain Zaman Janjua in Faisalabad, Pakistan

Thu, August 11, 2022

Tears of joy rolled down his wizened cheeks when Indian Sika Khan met his Pakistani brother for the first time since being separated by Partition in 1947.

Sikh labourer Sika was just six months old when he and his elder brother Sadiq Khan were torn apart as Britain split the subcontinent at the end of colonial rule.

This year marks the 75th anniversary of Partition, during which sectarian bloodshed killed possibly more than one million people, families like Sika's were cleaved apart and two independent nations -- Pakistan and India -- were created.

Sika's father and sister were killed in communal massacres, but Sadiq, just 10 years old, managed to flee to Pakistan.

"My mother could not bear the trauma and jumped into the river and killed herself," Sika said at his simple brick house in Bhatinda, a district in the western Indian state of Punjab, which bore the brunt of Partition violence.

"I was left at the mercy of villagers and some relatives who brought me up."

Ever since he was a child, Sika yearned to find out about his brother, the only surviving member of his family. But he failed to make headway until a doctor in the neighbourhood offered to help three years ago.

After numerous phone calls and the assistance of Pakistani YouTuber Nasir Dhillon, Sika was able to be reunited with Sadiq.

The brothers finally met in January at Kartarpur corridor, a rare, visa-free crossing that allows Indian Sikh pilgrims to visit a temple in Pakistan.

The corridor, which opened in 2019, has become a symbol of unity and reconciliation for separated families, despite the lingering hostilities between the two nations.

"I am from India and he is from Pakistan, but we have so much love for each other," said Sika, clutching a faded and framed family photograph.

"We hugged and cried so much when we met for the first time. The countries can keep on fighting. We don't care about India-Pakistan politics."

- Trains full of corpses -

Pakistani farmer and real estate agent Dhillon, 38, a Muslim, says he has helped reunite about 300 families through his YouTube channel together with his friend Bhupinder Singh, a Pakistani Sikh.

"This is not my source of income. It's my inner affection and passion," Dhillon told AFP. "I feel like these stories are my own stories or stories of my grandparents, so helping these elders I feel like I am fulfilling the wishes of my own grandparents."

He said he was deeply moved by the Khan brothers and did everything possible to ensure their reunion.

"When they were reunited at the Kartarpur, not only me but some 600 people at the compound wept so much seeing the brothers being reunited," he told AFP in Faisalabad, Pakistan.

Millions of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims are believed to have fled when British administrators began dismantling their empire in 1947.

One million people are estimated to have been killed, though some put the toll at double this figure.

Hindus and Sikhs fled to India, while Muslims fled in the opposite direction.

Tens of thousands of women and girls were raped and trains carrying refugees between the two new nations arrived full of corpses.

- Love transcends -

The legacy of Partition has endured to this day, resulting in a bitter rivalry between the nuclear-armed neighbours despite their cultural and linguistic links.

However, there is hope of love transcending boundaries.

For Sikhs Baldev and Gurmukh Singh, there was no hesitation in embracing their half-sister Mumtaz Bibi, who was raised Muslim in Pakistan.

As an infant, she was found alongside her dead mother during the riots and was adopted by a Muslim couple.

Their father, assuming his wife and daughter were dead, married his wife's sister, as was the norm.

The Singh brothers learned their sister was alive with the help of Dhillon's channel and a chance phone call to a shopkeeper in Pakistan.

The siblings finally met in the Kartarpur corridor earlier this year, breaking down at being able to see each other for the first time in their lives.

"Our happiness knew no bounds when we saw her for the first time," Baldev Singh, 65, told AFP. "So what if our sister is a Muslim? The same blood flows through her veins."

Mumtaz Bibi was equally ecstatic when an AFP team met her in the city of Sheikhupura in Pakistan's Punjab province.

"When I heard (about my brothers), I thought God is willing it. It is God's will, and one has to bow before his will and then he blessed me, and I found my brothers," she said.

"Finding those separated brings happiness. My separation has ended, so I am so content."

zz-abh/stu/lb/cwl

India Partition: After 75 years, tech opens a window into the past

LAHORE/NEW DELHI: Growing up, Guneeta Singh Bhalla heard her grandmother describe how she crossed into newly-independent India from Pakistan in 1947 with her young children, witnessing horrific scenes of carnage and violence that haunted her for the rest of her life.

Those stories were not in Singh Bhalla’s school textbooks, so she decided to create an online history — The 1947 Partition Archive, which contains about 10,500 oral histories, the biggest collection of Partition memories in South Asia.

“I didn’t want my grandmother’s story to be forgotten, nor the stories of others who experienced Partition,” said Singh Bhalla, who moved to the United States from India at age 10.

“With all its faults, Facebook is an incredibly powerful tool: the archive was built off of people finding us on Facebook and sharing our posts, which brought much more awareness,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

The partition of colonial India into two states, Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India, at the end of British rule triggered one of the biggest mass migrations in history.

About 15 million Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs swapped countries in the political upheaval, marred by violence and bloodshed that cost more than a million lives.

Pakistan and India have fought three wars since then, and relations remain tense. They rarely grant visas to each others’ citizens, making visits nearly impossible — but social media has helped people on either side of the border connect.

There are dozens of groups on Facebook and Instagram, as well as YouTube channels that tell the stories of Partition survivors and their occasional visits to ancestral homes, that rack up millions of shares and views, and emotional comments.

“Such initiatives that help document the experiences of Partition serve as an antidote to the charged political narratives of the two states,” said Ayesha Jalal, a South Asian history professor at Tufts University in the United States.

“They help to alleviate the tensions between the two sides, and open up channels for a much-needed people-to-people dialogue.”

VIRTUAL REALITY TAKES SURVIVORS HOME

As the number of those displaced from their homes has swelled worldwide, technology helps monitor abandoned homes from afar and records human rights abuses, while digital archives preserve cultural heritage.

Project Dastaan — meaning story in Urdu — uses virtual reality (VR) to document accounts of Partition survivors and enable them to revisit their place of birth.

“VR isn’t like film — there is a level of immersion and engagement that creates empathy and has a powerful impact,” said founder Sparsh Ahuja, whose grandfather migrated to India as a seven-year-old during the Partition.

“People really feel like they are transported to the place.”

Using volunteers in India and Pakistan to locate and film places — which have often changed dramatically over the decades — Project Dastaan had aimed to connect 75 Partition survivors with their ancestral homes by the 75th anniversary this year.

But pandemic restrictions meant that they only completed 30 interviews since they began filming in 2019, said Ahuja.

“When visa policies were more friendly, people could physically go and see places and people,” he said. “Now, these connections wouldn’t happen without technology, and VR has brought a whole new audience to the Partition experience.”

Among the most popular YouTube channels on Partition is Punjabi Lehar — or Punjabi wave — with about 600,000 subscribers.

Founder Lovely Singh, 30, part of the minority Sikh community in Pakistan, estimates that the channel has helped 200 to 300 individuals reconnect with family and friends.

Earlier this year, Punjabi Lehar’s video of an emotional reunion between two elderly brothers separated during Partition quickly went viral, drawing widespread praise.

“If we can help connect more people, maybe there will be less tension between the two countries,” said Singh.

“This is how my children are learning about the Partition.”

TENSIONS IN THE DIGITAL WORLD

Pakistan and India are among the biggest social media markets in the world, with more than 500 million YouTube and nearly 300 million Facebook users, according to research firms Global Media Insight and Statista.

History professor Jalal noted that these online spaces can also host misinformation, and added a note of caution about the limits of social media projects.

“While immensely useful, these initiatives surrounding the Partition should not be seen as a replacement to historical understandings of the causes of Partition,” she said.

Political tensions between India and Pakistan frequently spill over on to social media.

Last year, one Indian state said people who celebrated Pakistan’s win over India in a cricket match on social media could be charged with sedition, which carries a penalty of up to life in prison.

Indians — particularly Muslims — who criticise the government online are often told to “go to Pakistan”.

But for 90-year-old Reena Varma, social media has done more than make a virtual connection — it has enabled her to visit her old home in Rawalpindi 75 years after she left it.

When her Pakistan visa application was rejected earlier this year, the news went viral on Facebook. Islamabad intervened to give a visa to Varma, who migrated to India as a teenager weeks before the Partition.

When Varma visited Pakistan last month, Imran William, founder of the Facebook group the India Pakistan Heritage, was on hand to welcome her.

Residents beat drums and showered her with flowers as she danced on the street, then looked around her old home.

“It was very emotional, but I am so happy I could fulfil my dream of visiting my home,” Varma said.

“People have very painful memories of the Partition, but thanks to Facebook and other social media, people are interacting and keen to meet each other. It brings people of both countries together.”

India At 75: Dreams Of A Hindu Nation Leave Minorities Sleepless

The Hindu priest on the banks of the holy river Ganges spoke softly, but had a threatening message 75 years after the birth of independent India: his religion must be the heart of Indian identity.

"We must change with time," said Jairam Mishra. "Now we must cut every hand that is raised against Hinduism."

Hindus make up the overwhelming majority of India's 1.4 billion people but when Mahatma Gandhi secured its independence from Britain in 1947 it was as a secular, multi-cultural state.

Now right-wing calls for the country to be declared a Hindu nation and Hindu supremacy to be enshrined in law are growing rapidly louder, making its 210-million-odd Muslims increasingly anxious about their future.

Those demands are at the core of Hindu nationalist Prime Minister Narendra Modi's popularity, and his government has backed policies and projects across the country -- including a grand new temple corridor in the holy city of Varanasi -- that reinforce and symbolise the trend.

Gandhi was a devout Hindu but was adamant that in India "every man enjoys equality of status, whatever his religion is".

"The state is bound to be wholly secular," he said.

He was assassinated less than a year after India and Pakistan's independence and Partition in 1947, by a Hindu fanatic who considered him too tolerant towards Muslims.

And Mishra believes Gandhi's ideals are now out of date.

"If someone slaps you on one cheek," he told AFP, "Gandhi said we must offer the other one. Hindus are generally peaceful and quiet compared to other religions.

"They even hesitate in killing a mosquito but other communities are exploiting this mindset and will keep dominating us unless we change."

To many, that change is already under way, emphasised by the rhetoric of Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and symbolised by the big-ticket Hinduism-related projects with which it has enthused his sectarian base during its eight years in power.

A grand temple is under construction in the holy Hindu city of Ayodhya, where Hindu zealots destroyed a Mughal-era mosque three decades ago, triggering widespread sectarian violence that killed more than 1,000 people nationwide and was a catalyst for the stunning rise of right-wing politics.

The BJP has backed a $300 million, 210-metre statue off the Mumbai coast of Hindu warrior king Chhatrapati Shivaji, who successfully challenged the Islamic Mughal empire.

And nine months ago, Modi opened a grand temple corridor in his constituency of Varanasi with much fanfare, taking a televised dip in the Ganges.

He has represented the city since 2014, when he secured his first landslide national election victory, and his successes transforming its once-creaking amenities are recognised even by his critics.

"The infrastructure push, roads, riverbank projects and cleanliness -- everything's better," said Syed Feroz Hussain, 44.

But the Muslim hospital worker said he was "really worried" about his children's future.

"Unlike the past, there is also too much violence and killing over religion and a constant feeling of tension and hatred" between communities, he said.

Varanasi is in Uttar Pradesh -- India's most populous state, with more people than Brazil -- and at the forefront of the BJP's "Hindutva" agenda.

It has renamed nearby Allahabad back to Prayagraj, 450 years after the Mughal emperor Akbar changed the city's designation.

Authorities have carried out arbitrary demolitions of homes of individuals accused of crimes -- most them Muslims -- in what activists say is an unconstitutional attempt to crush minority dissent.

In Karnataka -- which saw a spate of attacks on Christians last year -- the BJP has backed a ban on hijab in schools, which triggered Muslim street protests.

Emboldened Hindu groups have laid claims to Muslim sites they say were built atop temples during Islamic rule -- including a centuries-old mosque next to the grand Varanasi corridor opened by Modi -- raising fears of a new Ayodhya.

A new wave of anti-Muslim riots was triggered in 2002 after a train carrying 59 Hindu pilgrims from the site was set on fire, and at least 1,000 people were hacked, shot and burned to death in Gujarat. Modi was the state's chief minister at the time and has been accused of not doing enough to stop the killing.

But Professor Harsh V Pant of King's College London said the BJP's rise was enabled by Gandhi's own Congress party, which ruled the country for decades.

While preaching secularism, it pandered to extremist elements in both major religions for electoral purposes, he said.

But the BJP tapped into Hindu sentiment after mobs demolished the Ayodhya mosque in 1992 and is now "central to Indian politics", Pant said.

"Everyone buys its narrative, responds to it and it feels no one else has any ideas," he said.

"They are here for the next two to three decades."

That shift is a boon to those who want to see India declared a Hindu nation, such as the right-wing Vishwa Hindu Parishad organisation.

"We're a Hindu nation because India's identity is Hindu," its leader Surendra Jain told AFP.

The "double face of secularism" had "become a curse, and threat for India's existence".

"It doesn't mean everyone else has to leave," he added. "They can live peacefully but the character and ethos of India will always be Hindu."

As prime minister, Modi has largely avoided the polarising rhetoric he employed during his tenure in Gujarat, but according to critics he often ignores incendiary comments by figures in his own party.

And his actions, they say, enable calls for a Hindu nation without explicitly endorsing them.

That worries Muslims. Nasir Jamal Khan, 52, caretaker of a Varanasi mosque, said there was a "sense of growing schism" even though "our forefathers were born here".

He hopes for a day when India's elected leaders stop talking about religion, and told AFP: "I see the PM as a father in the family. It doesn't behove a father to treat his children differently."

PM Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has undertaken a number of big-ticket Hinduism-related projects, with which it has enthused his sectarian base during its eight years in power

PM Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has undertaken a number of big-ticket Hinduism-related projects, with which it has enthused his sectarian base during its eight years in power

Those whose lived through the formation of India and Pakistan are telling their stories – and their grandchildren are asking questions

Sat 6 Aug 2022

Two sisters handed me a piece of paper that was faded and yellow. On it were typewritten words from their father. He had died in the 1990s and his final request had been for his ashes to be divided up and scattered in three different places: the Punjabi village in modern-day Pakistan where he’d been born, the River Ganges at Haridwar in India, and by the Severn Bridge in England. These three places made up his life, from displacement to India from Pakistan during partition, and then his migration to Britain. He felt he belonged in each one of them, wanting some part of him to remain, in death as in life.

Five years ago, I started collecting testimonies of the people in Britain who lived through the tumultuous events of partition. I quickly realised it was not a story from far away, but one that was all around us in Britain, with a continuing legacy.

The division of British India along religious lines in 1947, into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan, resulted in the largest migration outside wartime and famine in human history. As people found themselves a minority in a new country, an estimated 10-12 million people moved across a new border, leaving homes that had been lived in for generations. About a million people were killed in communal violence. More than 75,000 women were raped, abducted and forced to convert to the “other” religion.

So many families in Britain have a connection with partition, as those who migrated from the Indian subcontinent in the early postwar years were largely from places disrupted by it. They came to rebuild the country and their own lives. They arrived with those memories, which were rarely spoken out loud. But in 2017, during the 70th anniversary of partition, that silence began to break.

I travelled across Britain and was told shattering stories. I met a man with a 70-year-old scar indelibly etched on his arm from a poisoned spear. I cannot forget the sound of anguish he made as he explained he was left for dead, and almost died, as a mob entered his village. I listened as an elderly man sounded almost childlike as he described the horrors of waking up on a train platform full of dead bodies. A woman talked of overhearing her uncles planning to kill all the girls in her family to save them from dishonour, such was the fear of sexual violence. Her grandmother talked them down. So many stories like these had largely been hidden for decades, by people who live among us, and who still have nightmares from that time. And we never knew.

But the partition generation told other stories too, that they want remembered. Of a people who lived side by side for generations – Muslim, Sikh, Hindu – with languages, food and culture in common. There were deep friendships; they would share each other’s sorrow and joy, irrespective of religion. One man told me how a Muslim woman from his village breastfed his Sikh cousins after their mother died. What could be more intimate? There were accounts, too, of friends and strangers transcending hate to save those of the “other” religion. One man told me that on the day a Muslim mob killed his father, his Muslim neighbour saved his sister and 30 other Sikh girls by sheltering them in his home.

Now, that generation wonder out loud if they will ever visit their ancestral home before they die. Will they ever see the childhood best friend they never had time to say goodbye to? Does a favourite tree they climbed up still stand?

What I never imagined when I embarked on these interviews was that the legacy of partition in the UK could be so varied and complex. Trauma and fear can be passed down, even in silence. But so too can that lasting tie to the land that was left, even if no one returned. Sometimes that attachment is tangible. I have seen descendants who keep earth in a jar from Bangladesh on their fireplace, or who wear a pebble from Pakistan around their neck every day, or who cherish a saved heirloom from India – all places their forefathers left 75 years ago. These objects are often their only connection to that time and place. It is proof their family once existed in that land too, and it is meaningful to these young people today.

In all this time, the border has never been able to erase this history, memories or emotion. And in the five years since the 70th anniversary, there has been a quiet awakening to this hidden past among the descendants of those who lived through it.

For some families, that has meant gaining a new understanding of the very word “partition” itself, and how their elderly relatives were affected. For others, it has been the realisation that the beginnings of their family story can be traced to another country entirely, across a border.

I have seen descendants with earth in a jar, from a land their forefathers left almost 75 years ago

Many of those who contacted me to share their stories were third generation. They wanted to know their history beyond their ancestors who came here. They asked: “How do I question my relative about their past if the subject has never been broached before?” Others said: “I wish I had asked while my relatives were alive.” They must now find other ways to delve into their history. All around our country, these inheritors of partition are trying to piece together their family’s past: starting conversations with family members, visiting archives, educating themselves on their history, doing DNA tests and, in some cases, even returning to the land long fled.

The writer Elif Shafak notes that it is the third generation descended from immigrants who dig into memory: they have “older memories even than their parents. Their mothers and fathers tell them, ‘This is your home, forget about all that.’” For the people I spoke to, identity, in all its complexity, matters.

Of course, these are not just personal stories within families – they are part of our shared history. That’s because it was a British border, drawn to divide British India as the British empire started to be dismantled. Subjects of the Raj came to Britain and are its citizens, and multiple generations live in these isles in their millions today. Partition, the end of empire and the subsequent migration to the land of the former colonial ruler, could not be a more British story – one that everyone needs to know and learn about. Yet, it is not a compulsory part of the national curriculum in England. In Wales, Black, Asian and minority ethnic histories will become mandatory teachings from September.

As we approach the August anniversary, it is always bittersweet: joy at independence, but sadness at the loss suffered, which endures. A few days ago, I was emailed by a daughter to say her father, one of my interviewees, had died at the age of 92. A reminder that our link to this time is dwindling.

Seventy-five years on, in Britain we are all the inheritors of partition and empire. We must decide what to do with this inheritance; decide what is remembered and what is forgotten. The legacy will live on in ways we do not yet know. It happened long ago but, somehow, I feel we are only at the beginning of coming to terms with it – both within families, and in Britain.

Kavita Puri is the author of Partition Voices: Untold British Stories, a new edition of which is published on 21 July. Her documentary, Inheritors of Partition, will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 8 August at 9am and will be available on BBC Sounds

SHEIKH SAALIQ

Thu, August 11, 2022

NEW DELHI (AP) — The Aug. 5 demonstrations by India’s main opposition Congress party against soaring food prices and unemployment began like any other recent protest — an electorally weak opposition taking to the New Delhi streets against Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s massively popular government.

The protests, however, quickly took a turn when key Congress lawmakers led by Rahul Gandhi — Modi’s main opponent in the last two general elections — trooped to the Parliament, leading to fierce standoffs with police.

“Democracy is a memory (in India),” Gandhi later tweeted, describing the dramatic photographs that showed him and his party leaders being briefly detained by police.

Gandhi’s statement was largely seen as yet another frantic effort by a crisis-ridden opposition party to shore up its relevance and was dismissed by the government. But it resonated amid growing sentiment that India’s democracy — the world’s largest with nearly 1.4 billion people — is in retreat and its democratic foundations are floundering.

Experts and critics say trust in the judiciary as a check on executive power is eroding. Assaults on the press and free speech have grown brazen. Religious minorities are facing increasing attacks by Hindu nationalists. And largely peaceful protests, sometimes against provocative policies, have been stamped out by internet clampdowns and the jailing of activists.

“Most former colonies have struggled to put a lasting democratic process in place. India was more successful than most in doing that,” said Booker Prize-winning novelist and activist Arundhati Roy. “And now, 75 years on, to witness it being dismantled systematically and in shockingly violent ways is traumatic.”

Modi’s ministers say India’s democratic principles are robust, even thriving.

“If today there is a sense in the world that democracy is, in some form, the future, then a large part of it is due to India,” External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar said in April. “There was a time when, in this part of the world, we were the only democracy."

History is on Jaishankar's side.

At midnight on August 15, 1947, the red sandstone parliamentary building in the heart of India's capital echoed with the high-pitched voice of Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first prime minister.

“At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom," Nehru famously spoke, words that were heard over live radio by millions of Indians. Then he promised: “To the nations and peoples of the world, we send greetings and pledge ourselves to cooperate with them in furthering peace, freedom and democracy.”

It marked India’s transition from a British colony to a democracy — the first in South Asia — that has since transformed from a poverty-stricken nation into one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, earning itself a seat at the global high table and becoming a democratic counterweight to its authoritarian neighbor, China.

Apart from a brief interruption in 1975 when a formal emergency was declared under the Congress party rule that saw outright censorship, India clung doggedly to its democratic convictions — largely due to free elections, an independent judiciary that confronted the executive, a thriving media, strong opposition and peaceful transitions of power.

But experts and critics say the country has been gradually departing from some commitments and argue the backsliding has accelerated since Modi came to power in 2014. They accuse his populist government of using unbridled political power to undermine democratic freedoms and preoccupying itself with pursuing a Hindu nationalist agenda.

“The decline seems to continue across several core formal democratic institutions... such as the freedom of expression and alternative sources of information, and freedom of association," said Staffan I. Lindberg, political scientist and director of the V-Dem Institute, a Sweden-based research center that rates the health of democracies.

Modi's party denies this. A spokesperson, Shehzad Poonawalla, said India has been a “thriving democracy” under Modi's rule and has witnessed “reclamation of the republic.”

Most democracies are hardly immune to strains.

The number of countries experiencing democratic backsliding “has never been as high” as in the past decade, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance said last year, adding the U.S. to the list along with India and Brazil.

Still, the descent appears to be striking in India.

Earlier this year, the U.S.-based non-profit Freedom House downgraded India from a free democracy to "partially free.” The V-Dem Institute classified it as an “electoral autocracy” on par with Russia. And the Democracy Index published by The Economist Intelligence Unit called India a “flawed democracy.”

India’s Foreign Ministry has called the downgrades “inaccurate" and “distorted.” Many Indian leaders have said such reports are an intrusion in “internal matters," with India’s Parliament disallowing debates on them.

Globally, India strongly advocates democracy. During the inaugural Summit for Democracy organized by the U.S. in December, Modi asserted the “democratic spirit” is integral to India’s “civilization ethos.”

At home, however, his government is seen bucking that very spirit, with independent institutions coming under increasing scrutiny.

Experts point to long pending cases with India’s Supreme Court challenging the constitutionality of key decisions taken by Modi's government as major concerns.

They include cases related to a controversial citizenship review process that has already left nearly 2 million people in Assam state potentially stateless, the now revoked semi-autonomous powers pertaining to disputed Kashmir, the opaque campaign finance laws that are seen disproportionately favoring Modi’s party, and its alleged use of military-grade spyware to monitor political opponents and journalists.

India's judiciary, which is independent of the executive, has faced criticism in the past but the intensity has increased, said Deepak Gupta, a former Supreme Court judge.

Gupta said India’s democracy appears to be “on the downswing” due to the court’s inability to uphold civil liberties in some cases by denying people bail and the misuse of sedition and anti-terror laws by police, tactics that were also used by earlier governments.

“When it comes to adjudication of disputes... the courts have done a good job. But when it comes to their role as protectors of the rights of the people, I wish the courts had done more,” he said.

The country’s democratic health has also taken a hit due to the status of minorities.

The largely Hindu nation has been proud of its multiculturalism and has about 200 million Muslims. It also has a history of bloody sectarian violence, but hate speech and violence against Muslims have increased recently. Some states ruled by Modi’s party have used bulldozers to demolish the homes and shops of alleged Muslim protesters, a move critics say is a form of collective punishment.

The government has sought to downplay these attacks, but the incidents have left the minority community reeling under fear.

“Sometimes you need extra protection for the minorities so that they don’t feel that they are second-rate citizens,” said Gupta.

That the rising tide of Hindu nationalism has helped buoy the fortunes of Modi’s party is evident in its electoral successes. It has also coincided with a rather glaring fact: the ruling party has no Muslim lawmaker in the Parliament, a first in the history of India.

The inability to fully eliminate discrimination and attacks against other minorities like Christians, tribals and Dalits — who form the lowest rung of India’s Hindu caste hierarchy — has exacerbated these concerns. Even though the government sees the ascent of an indigenous woman as India's ceremonial president as a significant step toward equal representation, critics have cast their doubts calling it political optics.

Under Modi, India’s Parliament has also come under scrutiny for passing important laws with little debate, including a religious-driven citizenship law and controversial agricultural reform that led to massive protests. In a rare retreat, his government withdrew the farm laws and some saw it as a triumph of democracy, but that sentiment faded quickly with increased attacks on free speech and the press.

The country fell eight places, to 150, out of 180 countries in this year’s Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, which said “Indian journalists who are too critical of the government are subjected to all-out harassment and attack campaigns.”

Shrinking press freedoms in India date to previous governments but the last few years have been worse.

Journalists have been arrested. Some are stopped from traveling abroad. Dozens are facing criminal prosecution, including sedition. At the same time, the government has introduced sweeping regulatory laws for social media companies that give it more power to police online content.

“One has only to look around to see that the media has certainly shriveled up during Mr. Modi’s regime,” said Coomi Kapoor, journalist and author of “The Emergency: A Personal History,” which chronicles India’s only period of emergency.

“What happened in the emergency was upfront and there was no pretense. What is happening now is more gradual and sinister,” she said.

Still, optimists like Kapoor say not everything is lost “if India strengthens its democratic institutions" and "pins its hopes on the judiciary.”

“If the independence of the judiciary goes, then I’m afraid nothing will survive,” she said.

Others, however, insist India’s democracy has taken so many body blows that the future looks increasingly bleak.

“The damage is too structural, too fundamental," said Roy, the novelist and activist.

___

Associated Press journalist Rishi Lekhi contributed to this report.

A schoolgirl walks past a screen on which visitors can write their vision for India 2047 inside "Pradhamantri Museum," or Prime Minister Museum, in New Delhi, India, Aug. 3, 2022. As India, the world’s largest democracy, celebrates 75 years of independence on Aug. 15, its independent judiciary, diverse media and minorities are buckling under the strain, putting its democracy under pressure.