Many legal scholars in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s radical decision to reverse Roe v. Wade have focused on the dangerous implications of the court’s centuries-old worldview on protections for things such as same-sex marriage and contraception. This concern is real, but there is another issue with equally grave constitutional consequences, one that portends the emergence of a foundational alteration of American government itself.

Considered alongside two First Amendment rulings last term, the Dobbs decision marks a serious step in an emerging legal campaign by religious conservatives on the Supreme Court to undermine the bedrock concept of separation of church and state and to promote Christianity as an intrinsic component of democratic government.

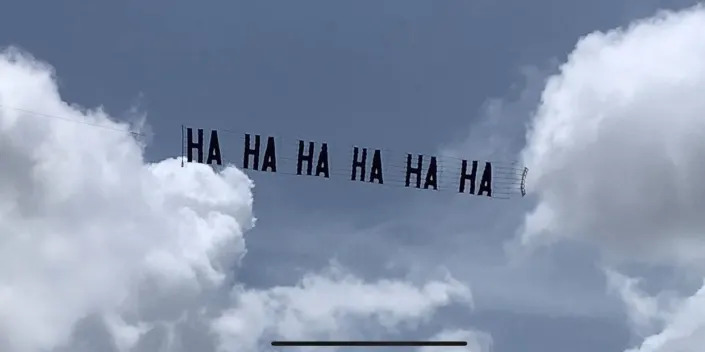

The energy behind this idea was apparent in Justice Samuel Alito’s speech last month for Notre Dame Law School’s Religious Liberty Initiative in Rome. Calling it an “honor” to have penned the 6-3 majority opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, and mocking international leaders for “lambast[ing]” the ruling, Alito spent the bulk of his remarks lamenting “the turn away from religion” in Western society. In his mind, the “significant increase in the percentage of the population that rejects religion” warrants a full-on “fight against secularism” — which Alito likened to staving off totalitarianism itself. Ignoring the vast historical record of human rights abuses in the name of religion (such as the Taliban in Afghanistan and even his own Catholic church’s role in perpetuating slavery in America), Alito identified the communist regimes of China and the Soviet Union as examples of what happens when freedom to worship publicly is curtailed. Protection for private worship, he argued, is not enough. Because “any judge who wants to shrink religious liberty” can just do it by interpreting the law, Alito insisted that there “must be limits” on that power.

The limits that Alito is referring to have begun to emerge as the court explicitly seeks to anchor its understanding of constitutional rights in early American history—or even earlier, under the English monarchy. Alito and his fellow conservatives evidently pine for a return to a more religiously homogenous, Christian society but to achieve it they are deliberately marginalizing one pillar of the First Amendment in favor of another. The dots connecting Alito’s personal mission to inculcate religion in American life and what the conservative majority is doing to the Constitution are easy to see. They begin with Dobbs.

Dobbs is significant not just because it reversed 50 years of precedent under the “due process clause” of the Fourteenth Amendment (under which the Court has recognized certain rights, even if unenumerated in the Constitution, as so bound up with the concept of liberty that the government cannot arbitrarily interfere with them). In Dobbs, Alito subverted that notion and fashioned a brand-new, two-part test for assessing the viability of individual rights: (1) whether the right is expressed in the Constitution’s text, and if not, (2) whether it existed as a matter of “the Nation’s history and tradition.” This second part of the test is the crucial one when it comes to religion — and in particular, its installation in government.

Under Dobbs’ step two, Alito time-traveled back to the Fourteenth Amendment’s ratification in 1868, when women could not even vote and, in his words, “three quarters of the States made abortion a crime at all stages of pregnancy.” Alito then regressed even earlier, to 13th century England (before America’s birth), to shore up his dubious quest to excavate historical authority rejecting abortion rights. Alito gave no guidelines for identifying which chapter of history counts in this calculus. Nor did he grapple with ancient law that actually went the other way. All we know going forward is that, for this majority, text is paramount and, barring that, very old history is determinative.

Except if the text appears in the First Amendment’s “establishment clause.” In a pair of other decisions, the same conservative majority pooh-poohed explicit constitutional language mandating that “Congress shall make no laws respecting an establishment of religion,” holding that a competing part of the First Amendment — which bars the federal government from “prohibiting the free exercise” of religion — is the more important and controlling.

The government cannot establish an official religion or ban public worship. But which clause governs if a government employee openly endorses religious beliefs at work in a way that could be attributed to the government or feel coercive to subordinates? Do the employee’s free exercise rights supersede the government’s obligation to maintain secularity?

Up until this term, the answer was that government employees can worship freely like the rest of us, just not necessarily in their official capacities. In Employment Division, Department of Human Resources v. Smith, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote for the Court in 1990 that so long as a generally applicable law is not written in a way that targets specific religious practices, it is constitutional under the free exercise clause even if it affects religious practices. And under Lemon v. Kurtzman, the Court held in 1971 that for establishment clause purposes, the government can touch upon religion only for secular reasons, such as busing children to parochial schools, and not to promote religion, inhibit religion or foster excessive entanglement with religion.

In June, a 6-3 majority in Carson v. Makin buried the establishment clause under the free exercise clause. It held that Maine’s requirement that only “nonsectarian” private schools can receive taxpayer-funded tuition assistance violates the First Amendment because it “operates to identify and exclude otherwise eligible schools on the basis of their religious exercise.” Maine’s requirement did not single out any religion, so it passed the Smith test for free exercise claims. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed out in dissent, “this Court has long recognized” that “the establishment clause requires that public education be secular and neutral as to religion.” By “assuming away an establishment clause violation,” she argued, the majority decision forces Maine taxpayers to fund religious education — in that case, schools that embrace an affirmatively Christian and anti-LGBTQ+ ideology. “[T]he consequences of the Court’s rapid transformation of the religion clauses must not be understated,” she warned, because it risks “swallowing the space between the religion clauses.”

But there’s more. In an opinion authored by Justice Neil Gorsuch, the same majority in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District championed a public high school football coach’s insistence on publicly praying on the field after a game, effectively overruling Lemon as an “ahistorical approach to the establishment clause.” “Here,” Gorsuch wrote, “a government entity sought to punish an individual for engaging in a brief, quiet, personal religious observance . . . on a mistaken view that it had a duty to ferret out and suppress religious observances even as it allows comparable secular speech.” The problem again, as Sotomayor complained in another dissent, is the pesky establishment clause: “This Court continues to dismantle the wall of separation between church and state that the framers fought to build.”

Especially alarming, though, is Justice Clarence Thomas’s concurring opinion in Kennedy. Under the free speech clause, he noted, the Court has held that “the first Amendment protects public employee speech only when it falls within the core of First Amendment protection —speech on matters of public concern.” Other types of on-the-job speech can be restrained. But Thomas added: “It remains an open question . . . if a similar analysis can or should apply to free-exercise claims in light of the ‘history’ and ‘tradition’ of the free exercise clause.” (Emphasis supplied.) In other words, although free speech in government employment is limited, U.S. history and tradition may signal a different outcome for religion in government.

After Dobbs, history and tradition at the time of the framing of the Constitution are now the linchpin of constitutional interpretation. And Thomas has explicitly connected the founding period — and national identity — with Christianity. In September 2021, he delivered a lecture about his Catholicism at the Notre Dame School of Law, linking Christianity and the founding as motivation for returning to his own faith: “As I rediscovered the God-given principles of the Declaration [of Independence] and our founding, I eventually returned to the Church, which had been teaching the same truths for millennia. [T]he Declaration endures because it . . . reflects the noble understanding of the justice of the Creator to his creatures.” In his recent speech, Alito recounted a personal experience in a Berlin museum when he encountered a “well-dressed woman and a young boy” looking at a rustic (presumably Christian) wooden cross. The boy asked, “Who is that man?” Alito perceived the child’s question as “a harbinger of what’s in store for our culture” — “hostility to religion or at least the traditional religious beliefs that are contrary to the new moral code that is ascendant in some sectors.”

Although less publicly explicit than Alito and Thomas about his views on religion in government, Gorsuch privately spoke in 2018 to the Thomistic Institute, a group that “exists to promote Catholic truth in our contemporary world by strengthening the intellectual formation of Christians . . . in the wider public square.” Justice Amy Coney Barrett has written that “[Catholic judges] are obliged . . . . to adhere to their church’s teaching on moral matters,” and gave a commencement address to Notre Dame law graduates advising that a “legal career is but a means to an end, and . . . . that end is building the kingdom of God.”

These views represent a marked departure from traditional judicial conservatism on the Supreme Court. In Zuni Public School Dist. No. 89 v. Department of Education, Justice Scalia in 2007 heavily criticized the Court’s 1892 declaration in Holy Trinity v. United States that the historical record of America demonstrated that the United States “is a Christian nation.” The Court has since “wisely retreated from” that view, he retorted.

Historical accounts at the time of the 1787 Constitutional Convention indicate that the Framers and political leaders largely believed that governmental endorsements of religion would result in tyranny and persecution. There was a “concerted campaign” from the Anti-Federalists to “discredit the Constitution as irreligious, which for many of its opponents was its principal flaw,” along with repeated attempts to add Christian verbiage to the Constitution. The ultimate rejection of religious language demonstrates that the Founders intended constitutional secularity. In his dissenting opinion in Carson, Justice Stephen Breyer quoted James Madison to underscore the point: “[C]ompelled taxpayer sponsorship of religion ‘is itself a signal of persecution,’ which ‘will destroy that moderation and harmony which the forbearance of our laws to intermeddle with Religion, has produced amongst its several sects.’”

As scholar Mokhtar Ben Barka explains, however, by the time the Court issued the opinion in Holy Trinity, “nineteenth-century America was a mild form of Protestant theocracy. In this period, Protestantism was America’s de facto established religion” and Protestants overwhelmingly held power in the government. Alas, there are plenty of historical cherries to pick if the Court – as it did in Dobbs – decides to tether non-secular government in “history and tradition.”

Keep in mind, too, that as Elizabeth Dias recently chronicled for the New York Times, the push for a Christian government is sweeping GOP politics, as well. At Cornerstone Christian Center, a church near Aspen, Rep. Lauren Boebert (R-Colo.) received a standing ovation after urging that “[t]he church is supposed to direct the government.” Republican nominee for Pennsylvania governor, Doug Mastriano, likewise called the separation of church and state a “myth.” “In November we are going to take our state back,” he said. “My God will make it so.”

Although polls show that declaring the United States a conservative Christian nation is a minority view, the same was said about the reversal of Roe. This Supreme Court clearly doesn’t care.