By AJ Willingham, CNN

Sat February 11, 2023

CNN —

In between star-studded advertisements and a whole lot of football, this year’s Super Bowl watchers are being taken to church.

“He Gets Us,” a campaign to promote Jesus and Christianity, is running two ads during the game as part of a staggering $100 million media investment. To many, the spots will be nothing new: “He Gets Us” content has been peppering TV screens, billboards and social media feeds since a national launch in 2022.

The campaign is arresting, portraying the pivotal figure of Christianity as an immigrant, a refugee, a radical, an activist for women’s rights and a bulwark against racial injustice and political corruption. The “He Gets Us” website features content about of-the-moment topics, like artificial intelligence and social justice.

“Whatever you are facing, Jesus faced it too,” the campaign claims.

It’s getting noticed. One of the campaign’s videos, titled “The Rebel,” has netted 122 million views on YouTube in 11 months. Google searches for “He Gets Us” have spiked since the beginning of the year.

The campaign is a natural fit with the NFL, whose games have long contained symbols of religion. Players often pray on the field and point to the heavens after touchdowns.

The NFL and religion have been closely linked. Here, Kansas City Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes prays before the AFC Championship game against the Cincinnati Bengals on January 29, 2023.Charlie Riedel/AP

But certain details about the “He Gets Us” ads have set off alarm bells among young people and those skeptical of religion, two groups the campaign is specifically to attract.

Some of the campaign’s major donors, and its holding company, have ties to conservative political aims and far-right ideologies that appear at odds with the campaign’s inclusive messaging.

The campaign has connections to anti-LGBT and anti-abortion laws

The chain of influence behind “He Gets Us” can be followed through public records and information on the campaign’s own site. The campaign is a subsidiary of The Servant Foundation, also known as the Signatry.

According to research compiled by Jacobin, a left-leaning news outlet, The Servant Foundation has donated tens of millions to the Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative Christian legal group. The ADF has been involved in several legislative pushes to curtail LGBTQ rights and quash non-discrimination legislation in the Supreme Court.

CNN has reached out to the Servant Foundation for comment.

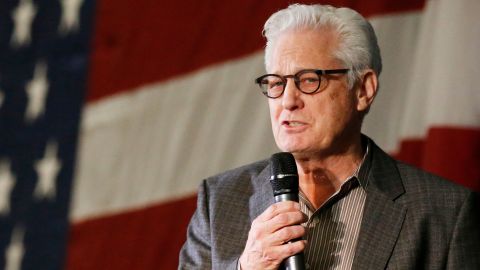

While donors who support “He Gets Us” can choose to remain anonymous, Hobby Lobby co-founder David Green claims to be a big contributor to the campaign’s multi-million-dollar coffers. Hobby Lobby has famously been at the center of several legal controversies, including the support of anti-LGBTQ legislation and a successful years-long legal fight that eventually led to the Supreme Court allowing companies to deny medical coverage for contraception on the basis of religious beliefs.

David Green, founder of Hobby Lobby, speaks at a campaign rally for then- presidential candidate Sen. Marco Rubio on February 29, 2016, in Oklahoma City.Sue Ogrocki/AP

Green discussed his involvement in the campaign, and the Super Bowl ad spots, during a November 2022 interview with conservative talk show host Glenn Beck.

“We are wanting to say — ‘we’ being a lot of different people — that he gets us,” Green said. “[Jesus] understands us. He loves who we hate. I think we have to let the public know and create a movement.”

“He Gets Us” does not list donors on its website. “Funding for He Gets Us comes from a diverse group of individuals and entities with a common goal of sharing Jesus’ story authentically,” the site’s funding information page reads. “Most of the people driving He Gets Us, including our donors, choose to remain anonymous because the story isn’t about them, and they don’t want the credit.”

Jason Vanderground, spokesperson for He Gets Us and president of creative marketing firm HAVEN, told CNN that The Servant Foundation uses a fund which “unites donors to provide pooled support for organizations while ensuring the organizations can operate without donors impacting specific messages.”

“Funding for the campaign comes from a diverse group of individuals and entities with a common goal of sharing Jesus’ story authentically,” he said.

The campaign is tied to evangelical churches

“Be assured … we’re not ‘left’ or ‘right’ or a political organization of any kind,” the “He Gets Us” site reads. “We’re also not affiliated with any particular church or denomination.”

While “He Gets Us” says it is not intended to be connected to any particular Christian ideology, it has theological ties to evangelical practices as well as financial ones. In general, Christian evangelism is closely tied to conservatism and is an extremely influential force in American politics.

On the “He Gets Us” outreach site, which is meant for churches and marketers who wish to interact with the campaign, the organization outlines its beliefs:

“He Gets Us has chosen to not have our own separate statement of beliefs. Each participating church/ministry will typically have its own language. Meanwhile, we generally recognize the Lausanne Covenant as reflective of the spirit and intent of this movement and churches that partner with explorers from He Gets Us affirm the Lausanne Covenant.”

This information does not appear to be listed anywhere on the main “He Gets Us” site intended for the public.

The 1974 Lausanne Covenant is an important unifying document in evangelical Christian churches, while the Lausanne movement itself was started by the prominent evangelical Christian leader Billy Graham. Documents and decisions that have come out of the movement’s summits have decried the “idolatry of disordered sexuality” and focused heavily on the impact of the devil and sin on national cultures.

The late evangelist Billy Graham at his home in the mountains near Asheville, North Carolina, on July 25, 2006.Charles Ommanney/Getty Images

The influence of Graham, a founder of modern American evangelism, is also evident in speakers and partners for “He Gets Us.” Some of them are affiliated with groups bearing Graham’s name, including the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College, a liberal arts institution in Illinois.

Though Wheaton College has a deep history of abolitionism and racial justice, Campus Pride also ranked it as one of the worst campuses for LGBTQ youth. Students are required to sign a Community Covenant stating Christianity condemns “sexual immorality,” including homosexuality and adultery.

CNN asked Vanderground, the representative for He Gets Us, if the campaign supports and affirms LGBTQ Christians.

“The debate over LGBTQ+ issues is a great example of how the real Jesus too often gets lost, overlooked or distorted in debates over political and social issues,” he said. “Our focus is on helping people see and consider Jesus as he is shown in the Bible … He gets us and he loves us, and that includes people on all sides of these issues.”

Some critics say the campaign is not authentic

The minds behind “He Gets Us” say the campaign’s message is intended to appeal to younger people and those who may see Christianity as “toxic” and divisive.

“A lot of times when people look at Christianity, unfortunately they see it as much more hypocritical, judgmental, discriminatory,” Vanderground told CNN’s Tom Foreman.

“We’re trying to unify the American people around the confounding love and forgiveness [of Jesus].”

The first of the "He Gets Us" campaign billboards appeared along the Strip in Las Vegas on March 14, 2022.Eric Jamison/AP

“By design, our media messages focus on his humanity—since we’ve learned these resonate with the widest possible audience,” the “He Gets Us” partner site reads. “We also provide open opportunities, for anyone willing, to connect with our partners to learn more about Jesus.”

Word of the campaign has sparked enthusiasm among Christian groups and influencers online. But other Christians, including those in the growing deconstruction movement who are reevaluating their relationship with religion, aren’t buying it.

Dr. Kevin M. Young, a pastor and biblical scholar who discusses Christianity on social media, says the campaign won’t do much to assuage people’s criticisms of the church.

“Young people are digital natives who understand the difference between slick marketing and authenticity,” he says. “Megachurches, mega-events, and mega spending on marketing is seen as money that could have been used funding community programs and advocacy for the oppressed – such as refugees, LGBTQ+ individuals and abortion rights – and the poor.”

Instead, Young says, they’d prefer to see action and accountability.

“Young people want a church that will put shoe leather to their faith and do something for those in harm’s way; those who the church itself has harmed.”

Some “He Gets Us” messaging makes oblique references to “cancel culture,” which raises a red flag for some who see the term as highly political and a staple of conservative rhetoric. One message uses the slogan, “Jesus was canceled.”

“When it comes to crucifixion and “cancel culture,” I don’t see much to compare,” writes Josiah R. Daniels for Sojourner, a Christian publication. “Furthermore, imagining Jesus as apolitical is itself a political decision — and it is a decision that aligns with politically and financially powerful interests.”

Other Christians have criticized the campaign for a different reason altogether: for being too vague and apparently de-emphasizing Biblical teachings and Jesus’ holiness.

Conservative pundit Charlie Kirk took aim at the campaign, saying those involved have been “taken for a ride by these woke tricksters.”

Vanderground says the campaign is “committed to being scripturally accurate.”

“[W]e believe it’s more important now than ever for the real, authentic Jesus to be represented in the public marketplace as he is in the Bible,” he told CNN.

Workers cover the field with a tarp ahead of a rehearsal for the Super Bowl LVII Halftime Show at State Farm Stadium in Glendale, Arizona.Caitlin O'Hara/Reuters

The ad campaign comes as Christian identity has waned in the US in recent decades. According to Pew Research data, about 63% of American adults identified as Christian in 2022, down from about 90% in the 1990s. Younger adults in particular are driving this downturn.

“Jesus doesn’t have an image problem, but Christians and their churches do,” Young says. “These campaigns end up being PR for the wrong problem. Young people are savvy. One of their primary issues with evangelicalism, and the modern church in America, is the amount of money spent on itself.”

The two new Super Bowl ads alone are a hefty spend, with 30-second spots for the game running a record-high $7 million in 2023. Vanderground told “Christianity Today” the campaign plans to invest a billion dollars on spreading their message.

It’s exactly that investment, and the people behind it, that have led some Christians to wonder if “He Gets Us” will actually lead people to Jesus – and if it does, what path they will ultimately be encouraged to take.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thenational/QH3BUX7CCZC5YIJUDE4KAUNCOU.jpg)