What to Know About the Lawsuits Against the Company at the Center of the Ohio Train Derailment

Anisha Kohli

Sat, February 18, 2023

Train derailment in East Palestine

Officials continue to conduct operation and inspect the area after the train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, on February 17, 2023. Credit - US Environmental Protection Agency—Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Rail operator Norfolk Southern is now facing a slew of lawsuits over its derailed cargo train in East Palestine, Ohio on Feb. 3 that caused a massive fire and toxic chemical spill.

The rail company’s actions are being criticized as a major environmental and health crisis and the derailment as “wholly preventable,” according to one of numerous lawsuits brought by concerned community members.

After the crash, residents within a mile radius of the crash had to evacuate the area and those within three miles had to shelter in place when toxic chemicals, including vinyl chloride, spilled and caused residents to worry about the health risks of such exposure, the environmental impact on the region and the economic repercussions of evacuating

“From chemicals that cause nausea and vomiting to a substance responsible for the majority of chemical warfare deaths during World War I, the people of East Palestine and the surrounding communities are facing an unprecedented array of threats to their health,” Attorneys Frank Petosa and Rene Rocha at Morgan & Morgan, who represent a group of plaintiffs in a class action lawsuit against Norfolk Southern, said in a statement on Feb. 15.

So far, eight lawsuits have been filed against Norfolk Southern, alleging negligence and seeking more than $5 million for property damage, economic loss due to evacuation and exposure to toxic chemicals.

“While the lives impacted by this wholly preventable catastrophe may never be the same, we are committed to holding Norfolk Southern accountable for its actions and inactions and securing justice for those whose lives have been disrupted and remain in danger,” the attorneys added.

Here’s what to know:

Norfolk Southern’s response to the spill

The derailed train made up of 50 cars struck East Palestine, a rural village home to about 4,700 people, near Ohio’s Pennsylvania border. Eleven of the cars were carrying hazardous materials, including vinyl chloride, a flammable gas and carcinogen recognized by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Spilled chemicals from the derailment killed 3,500 fish in nearby streams, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. One of the lawsuits claims that thousands of residents in the region from Ohio to Pennsylvania could have been exposed to the toxic chemicals.

Authorities monitoring the scene were concerned about the risk of explosions following the derailment. On Feb. 6, Norfolk Southern decided to release and burn additional vinyl chloride, as a controlled release initiative that the company said would help avert the risk of explosions.

The company has said they are continuing to work to remove contaminants from the ground and streams following the spill, as well as monitoring air quality.

“We are here and will stay here for as long as it takes to ensure your safety and to help East Palestine recover and thrive,” Norfolk Southern President and CEO Alan Shaw said in a statement Thursday.

About the lawsuits

A lawsuit brought by Morgan & Morgan on behalf of residents in the derailment zone alleges that Norfolk Southern pumped more than 1.1 million pounds of vinyl chloride into the air. “I’m not sure Norfolk Southern could have come up with a worse plan to address this disaster,” Morgan & Morgan attorney John Morgan said in a statement.

The lawsuits allege that Norfolk Southern chose a cheaper, less safe method to contain the damage by releasing more chemicals, rather than safely and properly cleaning up the spill.

“Residents exposed to vinyl chloride may already be undergoing DNA mutations that could linger for years or even decades before manifesting as terrible and deadly cancers,” Morgan said in a statement. “Norfolk Southern made it worse by essentially blasting the town with chemicals as they focused on restoring train service and protecting their shareholders.”

Norfolk Southern has not commented directly on litigation, but in a statement Thursday, the company said that it will continue the ongoing cleanup efforts—which include removing contaminated soil and liquid—as well as distribute more than $2 million to help with evacuation costs and create a $1 million community fund.

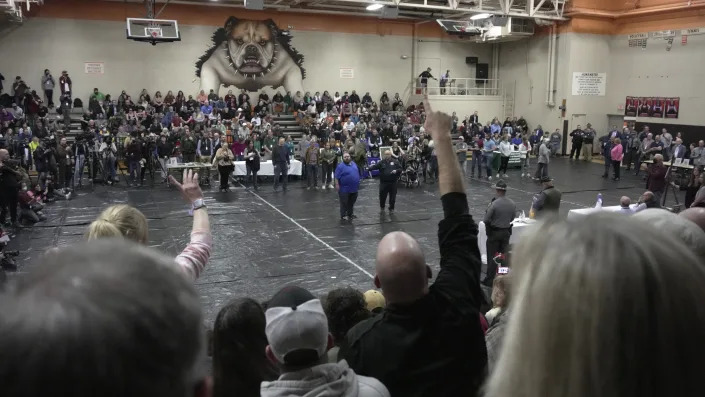

Community leaders in East Palestine organized a town hall on Wednesday to meet and address people’s health and safety concerns from the derailment. Representatives from Norfolk Southern didn’t show up to the event, citing that the company’s employees faced “threats.”

“Unfortunately, after consulting with community leaders, we have become increasingly concerned about the growing physical threat to our employees and members of the community around this event stemming from the increasing likelihood of the participation of outside parties,” Norfolk Southern said in a statement.

East Palestine authorities told TIME that they had not received any reports of threats against Norfolk Southern employees.

Anisha Kohli

Sat, February 18, 2023

Train derailment in East Palestine

Officials continue to conduct operation and inspect the area after the train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, on February 17, 2023. Credit - US Environmental Protection Agency—Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Rail operator Norfolk Southern is now facing a slew of lawsuits over its derailed cargo train in East Palestine, Ohio on Feb. 3 that caused a massive fire and toxic chemical spill.

The rail company’s actions are being criticized as a major environmental and health crisis and the derailment as “wholly preventable,” according to one of numerous lawsuits brought by concerned community members.

After the crash, residents within a mile radius of the crash had to evacuate the area and those within three miles had to shelter in place when toxic chemicals, including vinyl chloride, spilled and caused residents to worry about the health risks of such exposure, the environmental impact on the region and the economic repercussions of evacuating

“From chemicals that cause nausea and vomiting to a substance responsible for the majority of chemical warfare deaths during World War I, the people of East Palestine and the surrounding communities are facing an unprecedented array of threats to their health,” Attorneys Frank Petosa and Rene Rocha at Morgan & Morgan, who represent a group of plaintiffs in a class action lawsuit against Norfolk Southern, said in a statement on Feb. 15.

So far, eight lawsuits have been filed against Norfolk Southern, alleging negligence and seeking more than $5 million for property damage, economic loss due to evacuation and exposure to toxic chemicals.

“While the lives impacted by this wholly preventable catastrophe may never be the same, we are committed to holding Norfolk Southern accountable for its actions and inactions and securing justice for those whose lives have been disrupted and remain in danger,” the attorneys added.

Here’s what to know:

Norfolk Southern’s response to the spill

The derailed train made up of 50 cars struck East Palestine, a rural village home to about 4,700 people, near Ohio’s Pennsylvania border. Eleven of the cars were carrying hazardous materials, including vinyl chloride, a flammable gas and carcinogen recognized by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Spilled chemicals from the derailment killed 3,500 fish in nearby streams, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. One of the lawsuits claims that thousands of residents in the region from Ohio to Pennsylvania could have been exposed to the toxic chemicals.

Authorities monitoring the scene were concerned about the risk of explosions following the derailment. On Feb. 6, Norfolk Southern decided to release and burn additional vinyl chloride, as a controlled release initiative that the company said would help avert the risk of explosions.

The company has said they are continuing to work to remove contaminants from the ground and streams following the spill, as well as monitoring air quality.

“We are here and will stay here for as long as it takes to ensure your safety and to help East Palestine recover and thrive,” Norfolk Southern President and CEO Alan Shaw said in a statement Thursday.

About the lawsuits

A lawsuit brought by Morgan & Morgan on behalf of residents in the derailment zone alleges that Norfolk Southern pumped more than 1.1 million pounds of vinyl chloride into the air. “I’m not sure Norfolk Southern could have come up with a worse plan to address this disaster,” Morgan & Morgan attorney John Morgan said in a statement.

The lawsuits allege that Norfolk Southern chose a cheaper, less safe method to contain the damage by releasing more chemicals, rather than safely and properly cleaning up the spill.

“Residents exposed to vinyl chloride may already be undergoing DNA mutations that could linger for years or even decades before manifesting as terrible and deadly cancers,” Morgan said in a statement. “Norfolk Southern made it worse by essentially blasting the town with chemicals as they focused on restoring train service and protecting their shareholders.”

Norfolk Southern has not commented directly on litigation, but in a statement Thursday, the company said that it will continue the ongoing cleanup efforts—which include removing contaminated soil and liquid—as well as distribute more than $2 million to help with evacuation costs and create a $1 million community fund.

Community leaders in East Palestine organized a town hall on Wednesday to meet and address people’s health and safety concerns from the derailment. Representatives from Norfolk Southern didn’t show up to the event, citing that the company’s employees faced “threats.”

“Unfortunately, after consulting with community leaders, we have become increasingly concerned about the growing physical threat to our employees and members of the community around this event stemming from the increasing likelihood of the participation of outside parties,” Norfolk Southern said in a statement.

East Palestine authorities told TIME that they had not received any reports of threats against Norfolk Southern employees.

Professor: Oily sheen on East Palestine creek behaving like vinyl chloride

Emily Mills and Saleen Martin, Akron Beacon Journal

Sat, February 18, 2023

A viral video showing an oily sheen on a creek near the site of the toxic train derailment appears to show vinyl chloride, one of the chemicals released from a Norfolk Southern train in East Palestine.

"That looks like the way that I would expect the vinyl chloride to behave," said John Senko, a professor of geosciences and biology at the University of Akron, noting he did not know the proximity of the video to the derailment.

"It looks like what's happening is you got some of that stuff on the bottom of the creek, you stir it up a little bit, it starts to come up and then it's just going to sink again," he said. "So that stuff's behaving like I would expect vinyl chloride to behave.”

Where did the train come from?Cars carrying toxic chemicals traveled through many northern Ohio cities before derailing

The video, posted by U.S. Sen. J.D. Vance, R-Ohio, during a Thursday visit to the site of the Feb. 3 derailment, has been viewed more than 4 million times.

Investigators believe a wheel bearing in the final stage of overheat failure occurred moments before the derailment, the National Transportation Safety Board said Tuesday.

Of the 50 cars on the 141-car train that derailed, 11 were carrying hazardous materials. Five contained vinyl chloride, a colorless gas used to make hard plastic resin in products like credit cards and PVC pipes. Officials feared the cars would explode, so the vinyl chloride was burned on Feb. 6.

Clean water is pumped in Sulphur Run in East Palestine, Ohio, on Feb. 11.

Videos of oily sheens in East Palestine waterways

In the video Vance posted on Twitter, he's standing next to a waterway.

“So I’m here at Leslie Run, and there’s dead worms and dead fish all throughout this water,” he said in the video. “Something I just discovered is that if you scrape the creek bed, it’s like chemical is coming out of the ground.”

Derailment: Maps and graphics explain toxic train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio

Vance then uses a stick to scrape the bottom of the waterway, which causes an oily sheen to appear on the top of the water.

Expert stresses need for groundwater monitoring

Kuldeep Singh, an assistant professor in Kent State University’s earth sciences department, said the videos may show chemicals went through the streams and into the groundwater.

When the streambed sediments are stirred, contaminants are released, he said.

Another possibility, Singh said, is after the spill, naturally occurring materials like decaying leaf litter, biofilms or clays absorbed the chemicals.

He stressed that so often, people focus on issues that can be easily seen. However, there are also chemicals present that are harder to trace, including groundwater contamination, which he calls "the invisible part of this puzzle."

It could be a year or two before groundwater contamination is traceable in local wells due to how slowly it moves, he said.

Asked whether the rainbow slicks could have been caused by other natural processes, Singh said there is a chance.

“Any aerobic decomposition of specific kinds of algae may create some of these sheens, but not the ones that I'm seeing,” he said.

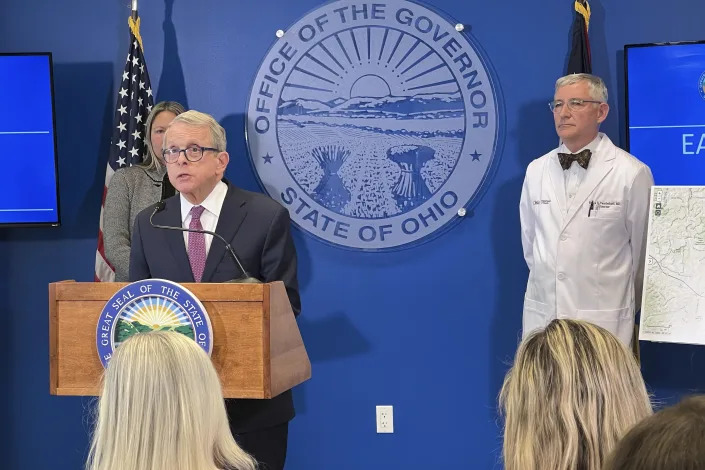

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine on Friday said it's now safe for residents to drink from the municipal water system. Officials are still urging people with private wells to get their supply tested and drink bottled water out of caution.

In an apparent reference to Vance's video, DeWine said Sulphur Run remains severely contaminated but was dammed to prevent it from running into other waterways.

The EPA has said thousands of fish have been killed in various creeks around and near Columbiana County, where East Palestine sits.

East Palestine train derailment updates:Chemical plume in Ohio River has dissipated

East Palestine acid rain:Is there acid rain in Ohio? What to know after East Palestine train derailment

Hoses along Sulphur Run creek are part of an attempt to clean the water after the Feb. 3 Norfolk Southern train derailment.

How can vinyl chloride be cleaned up?

Senko said that possible ways vinyl chloride can be removed include microorganisms that can convert it to less toxic compounds under certain conditions or vacuuming it out. "But that's tough," he said, adding it would be expensive, time-consuming and generate a lot of waste in the form of contaminated sediment.

Cautioning that he doesn't know what will actually happen, Senko said one possibility would be to just leave it there.

"Another thing that may happen ... is they would just say all right, it's there. Hopefully you can just cover it up with more stuff and just keep our fingers crossed that the sediments don't get swirled up all the time, and eventually it just kind of gets buried and (we) won't have to worry about it," he said.

Senko said "that's not desirable" but noted a similar process, not necessarily involving vinyl chloride, happened at Akron's Summit Lake, which was the source of cooling water for local factories in the early 20th century. Because the water came back laden with heavy metals, oils and chemicals from the factories, Summit Lake was too polluted for recreational use for years.

As part of the Akron Civic Commons project, the water and sediments at the bottom of the lake were tested, with the results showing that over the decades, the lake has naturally cleaned itself, with water quality improving.

More train derailments:Trains are becoming less safe. Why the Ohio derailment disaster could happen more often

Saleen D. Martin of USA TODAY, Kelly Byer of the Canton Repository and Haley BeMiller and Monroe Trombly of the Columbus Dispatch contributed to this report. Contact Beacon Journal reporter Emily Mills at emills@thebeaconjournal.com and on Twitter @EmilyMills818.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Oily sheen in Vance video behaving like vinyl chloride, expert says

Emily Mills and Saleen Martin, Akron Beacon Journal

Sat, February 18, 2023

A viral video showing an oily sheen on a creek near the site of the toxic train derailment appears to show vinyl chloride, one of the chemicals released from a Norfolk Southern train in East Palestine.

"That looks like the way that I would expect the vinyl chloride to behave," said John Senko, a professor of geosciences and biology at the University of Akron, noting he did not know the proximity of the video to the derailment.

"It looks like what's happening is you got some of that stuff on the bottom of the creek, you stir it up a little bit, it starts to come up and then it's just going to sink again," he said. "So that stuff's behaving like I would expect vinyl chloride to behave.”

Where did the train come from?Cars carrying toxic chemicals traveled through many northern Ohio cities before derailing

The video, posted by U.S. Sen. J.D. Vance, R-Ohio, during a Thursday visit to the site of the Feb. 3 derailment, has been viewed more than 4 million times.

Investigators believe a wheel bearing in the final stage of overheat failure occurred moments before the derailment, the National Transportation Safety Board said Tuesday.

Of the 50 cars on the 141-car train that derailed, 11 were carrying hazardous materials. Five contained vinyl chloride, a colorless gas used to make hard plastic resin in products like credit cards and PVC pipes. Officials feared the cars would explode, so the vinyl chloride was burned on Feb. 6.

Clean water is pumped in Sulphur Run in East Palestine, Ohio, on Feb. 11.

Videos of oily sheens in East Palestine waterways

In the video Vance posted on Twitter, he's standing next to a waterway.

“So I’m here at Leslie Run, and there’s dead worms and dead fish all throughout this water,” he said in the video. “Something I just discovered is that if you scrape the creek bed, it’s like chemical is coming out of the ground.”

Derailment: Maps and graphics explain toxic train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio

Vance then uses a stick to scrape the bottom of the waterway, which causes an oily sheen to appear on the top of the water.

Expert stresses need for groundwater monitoring

Kuldeep Singh, an assistant professor in Kent State University’s earth sciences department, said the videos may show chemicals went through the streams and into the groundwater.

When the streambed sediments are stirred, contaminants are released, he said.

Another possibility, Singh said, is after the spill, naturally occurring materials like decaying leaf litter, biofilms or clays absorbed the chemicals.

He stressed that so often, people focus on issues that can be easily seen. However, there are also chemicals present that are harder to trace, including groundwater contamination, which he calls "the invisible part of this puzzle."

It could be a year or two before groundwater contamination is traceable in local wells due to how slowly it moves, he said.

Asked whether the rainbow slicks could have been caused by other natural processes, Singh said there is a chance.

“Any aerobic decomposition of specific kinds of algae may create some of these sheens, but not the ones that I'm seeing,” he said.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine on Friday said it's now safe for residents to drink from the municipal water system. Officials are still urging people with private wells to get their supply tested and drink bottled water out of caution.

In an apparent reference to Vance's video, DeWine said Sulphur Run remains severely contaminated but was dammed to prevent it from running into other waterways.

The EPA has said thousands of fish have been killed in various creeks around and near Columbiana County, where East Palestine sits.

East Palestine train derailment updates:Chemical plume in Ohio River has dissipated

East Palestine acid rain:Is there acid rain in Ohio? What to know after East Palestine train derailment

Hoses along Sulphur Run creek are part of an attempt to clean the water after the Feb. 3 Norfolk Southern train derailment.

What is vinyl chloride?

Vinyl chloride, a colorless gas used to make the hard plastic resin, is a carcinogen, and burning it releases phosgene, a toxic gas that was used as a weapon during World War I, and hydrogen chloride into the air, according to USA TODAY.

"It's not good stuff. It's a carcinogen," Senko, from the University of Akron, said. "It has the potential to cause some kind of cancer if you're exposed to it for long periods of time. And I guess maybe the big problem with it is it’s just not going to go away."

Senko said vinyl chloride is difficult to remove because it's more dense than water, so it sinks to the bottom.

"The big reason that it's tough to remove is because it doesn't dissolve in the water, and so it just kind of stays there and kind of releases little bits over really long periods of time," he said.

Norfolk Southern lawsuits:Norfolk Southern released 1.1M pounds of vinyl chloride after derailment, lawsuit alleges

Vinyl chloride, a colorless gas used to make the hard plastic resin, is a carcinogen, and burning it releases phosgene, a toxic gas that was used as a weapon during World War I, and hydrogen chloride into the air, according to USA TODAY.

"It's not good stuff. It's a carcinogen," Senko, from the University of Akron, said. "It has the potential to cause some kind of cancer if you're exposed to it for long periods of time. And I guess maybe the big problem with it is it’s just not going to go away."

Senko said vinyl chloride is difficult to remove because it's more dense than water, so it sinks to the bottom.

"The big reason that it's tough to remove is because it doesn't dissolve in the water, and so it just kind of stays there and kind of releases little bits over really long periods of time," he said.

Norfolk Southern lawsuits:Norfolk Southern released 1.1M pounds of vinyl chloride after derailment, lawsuit alleges

How can vinyl chloride be cleaned up?

Senko said that possible ways vinyl chloride can be removed include microorganisms that can convert it to less toxic compounds under certain conditions or vacuuming it out. "But that's tough," he said, adding it would be expensive, time-consuming and generate a lot of waste in the form of contaminated sediment.

Cautioning that he doesn't know what will actually happen, Senko said one possibility would be to just leave it there.

"Another thing that may happen ... is they would just say all right, it's there. Hopefully you can just cover it up with more stuff and just keep our fingers crossed that the sediments don't get swirled up all the time, and eventually it just kind of gets buried and (we) won't have to worry about it," he said.

Senko said "that's not desirable" but noted a similar process, not necessarily involving vinyl chloride, happened at Akron's Summit Lake, which was the source of cooling water for local factories in the early 20th century. Because the water came back laden with heavy metals, oils and chemicals from the factories, Summit Lake was too polluted for recreational use for years.

As part of the Akron Civic Commons project, the water and sediments at the bottom of the lake were tested, with the results showing that over the decades, the lake has naturally cleaned itself, with water quality improving.

More train derailments:Trains are becoming less safe. Why the Ohio derailment disaster could happen more often

Saleen D. Martin of USA TODAY, Kelly Byer of the Canton Repository and Haley BeMiller and Monroe Trombly of the Columbus Dispatch contributed to this report. Contact Beacon Journal reporter Emily Mills at emills@thebeaconjournal.com and on Twitter @EmilyMills818.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Oily sheen in Vance video behaving like vinyl chloride, expert says

Kelly Byer, The Repository

Fri, February 17, 2023

A black plume rises over East Palestine, Ohio, as a result of a controlled detonation of a portion of the derailed Norfolk and Southern trains Monday, Feb. 6, 2023.

(AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar)

A new federal lawsuit claims fish and wild animals are dying as far as 20 miles away from the site of a train derailment and controlled burn of chemicals in East Palestine.

The Sandusky-based Murray & Murray law firm on Thursday filed a class-action complaint on behalf of three East Palestine residents, their relatives and other residents within a two-mile radius of the crash site and property owners within a 100-mile radius. It's one of at least seven lawsuits filed against Norfolk Southern since the Feb. 3 derailment.

While the release of chemicals is believed to have killed about 3,500 fish across 7.5 miles of streams, officials have yet to confirm any nonaquatic wildlife deaths connected to the derailment.

The Columbiana County Humane Society told the Herald-Star in Steubenville that it is compiling reports of sick animals as far as seven miles outside the evacuation zone. And the Ohio Department of Agriculture is testing tissue from a six-week-old beef calf that died Feb. 11 about two miles outside East Palestine, according to the Ohio Emergency Management Agency.

Previous cases:Norfolk Southern faces several lawsuits over East Palestine derailment, chemical release

Vinyl chloride, which was burned in several train cars to avoid a possible explosion, is a gas used to make hard plastic resin in plastic products and is associated with an increased risk of liver cancer and other cancers, according to the federal government's National Cancer Institute.

Officials warned the controlled burn of cars containing the gas would send toxic gas phosgene and hydrogen chloride into the air.

The latest lawsuit, filed in the U.S. District Court's Northern District of Ohio, claims that Norfolk Southern was negligent in its transportation of hazardous material and its response to the derailment. It also holds the company liable for the resulting harm and losses.

"Mass kills of wild animals and fish have been reported as far as 20 miles away from the Derailment Site," it says. "Although mandatory evacuation orders have been lifted and residents have been told that it is safe to return to their homes, plaintiffs and members of their class believe, with good reason, that the prospective dangers from the hazardous exposure are being grossly downplayed and that their health has been and is subjected to injurious toxins."

Norfolk Southern's media relations team said via email that they are "unable to comment on litigation."

Battaglia by Rick Armon on Scribd

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency identified four toxic chemicals known to have been released into the air, surface soils and surface waters: vinyl chloride, butyl acrylate, ethylhexyl acrylate and ethylene glycol monobutyl ether.

Isobutylene also was in the rail cars and tankers that were "derailed, breached, and/or on fire," according to a general notice of potential liability letter the EPA sent Feb. 10 to Norfolk Southern. A document from Norfolk Southern detailing the train cars and damage states that the isobutylene tanker was not breached.

The EPA found contaminants from the derailment site in samples from Sulphur Run, Leslie Run, Bull Creek, North Fork Little Beaver Creek, Little Beaver Creek and the Ohio River.

The plaintiffs had not returned to their homes by Thursday and "are faced with the prospect that the real and personal property they own may be damaged beyond their lifetimes and is now worth far less and might be or become unsaleable," according to the lawsuit.

They are seeking monetary damages for "economic and non-economic damages" among other various fees and court costs.

This article originally appeared on The Repository: Lawsuit claims fish, animals dying 20 miles away from East Palestine

How dangerous train derailments affect communities like East Palestine, Ohio

Caitlin Dickson and Christopher Wilson

Sat, February 18, 2023

A woman takes a photo of a train that derailed in Sandusky, Ohio, in October 2022. (Gina Bates/Facebook)

Four months before a Norfolk Southern train carrying toxic chemicals ran off the tracks in East Palestine, Ohio, creating a fiery explosion that burned for days, another cargo train operated by the same company derailed at an overpass roughly 140 miles away, in Sandusky, Ohio.

Fortunately, no one was injured as a result of the Sandusky derailment, which caused several rail cars to overturn and fall onto one of the main roads leading in and out of the city. The train had been hauling paraffin wax, some of which leaked from the derailed cars and into the city’s sewers, but it quickly hardened and reportedly posed no danger, according to city officials. Roughly 1,500 people were temporarily left without power after the crash, and Amtrak was forced to reroute many of its trains while railroad workers rushed to repair the line. Although the railroad was back up and running a week later, the underpass below remained closed to vehicles and pedestrians for months.

Days after the derailment, a prescient editorial in the Sandusky Register called for a thorough and transparent investigation into the derailment, arguing that “knowing full well the cause for what happened is the first, most important step in preventing it from happening again.”

“It could have been catastrophic, but, fortunately, the loss of life and serious injury both were avoided if only by luck,” the Register’s editorial board wrote. “But the next time, if something like this happens again, it could be more devastating, and someone could be hurt or killed. It seems like pure luck everyone escaped safely this time.”

Sandusky wasn’t the only city in Ohio to experience a train derailment in the months leading up to the crash in East Palestine. In early November, 22 cars of a 237-car train transporting rock salt and other materials derailed in Ravenna Township, a municipality of fewer than 9,000 people roughly 20 miles east of Akron. Days later, another train carrying garbage derailed between Toronto and Steubenville, dumping garbage into the Ohio River. Both of those trains also belonged to Norfolk Southern, one of the nation’s largest railroad companies.

A new federal lawsuit claims fish and wild animals are dying as far as 20 miles away from the site of a train derailment and controlled burn of chemicals in East Palestine.

The Sandusky-based Murray & Murray law firm on Thursday filed a class-action complaint on behalf of three East Palestine residents, their relatives and other residents within a two-mile radius of the crash site and property owners within a 100-mile radius. It's one of at least seven lawsuits filed against Norfolk Southern since the Feb. 3 derailment.

While the release of chemicals is believed to have killed about 3,500 fish across 7.5 miles of streams, officials have yet to confirm any nonaquatic wildlife deaths connected to the derailment.

The Columbiana County Humane Society told the Herald-Star in Steubenville that it is compiling reports of sick animals as far as seven miles outside the evacuation zone. And the Ohio Department of Agriculture is testing tissue from a six-week-old beef calf that died Feb. 11 about two miles outside East Palestine, according to the Ohio Emergency Management Agency.

Previous cases:Norfolk Southern faces several lawsuits over East Palestine derailment, chemical release

Vinyl chloride, which was burned in several train cars to avoid a possible explosion, is a gas used to make hard plastic resin in plastic products and is associated with an increased risk of liver cancer and other cancers, according to the federal government's National Cancer Institute.

Officials warned the controlled burn of cars containing the gas would send toxic gas phosgene and hydrogen chloride into the air.

The latest lawsuit, filed in the U.S. District Court's Northern District of Ohio, claims that Norfolk Southern was negligent in its transportation of hazardous material and its response to the derailment. It also holds the company liable for the resulting harm and losses.

"Mass kills of wild animals and fish have been reported as far as 20 miles away from the Derailment Site," it says. "Although mandatory evacuation orders have been lifted and residents have been told that it is safe to return to their homes, plaintiffs and members of their class believe, with good reason, that the prospective dangers from the hazardous exposure are being grossly downplayed and that their health has been and is subjected to injurious toxins."

Norfolk Southern's media relations team said via email that they are "unable to comment on litigation."

Battaglia by Rick Armon on Scribd

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency identified four toxic chemicals known to have been released into the air, surface soils and surface waters: vinyl chloride, butyl acrylate, ethylhexyl acrylate and ethylene glycol monobutyl ether.

Isobutylene also was in the rail cars and tankers that were "derailed, breached, and/or on fire," according to a general notice of potential liability letter the EPA sent Feb. 10 to Norfolk Southern. A document from Norfolk Southern detailing the train cars and damage states that the isobutylene tanker was not breached.

The EPA found contaminants from the derailment site in samples from Sulphur Run, Leslie Run, Bull Creek, North Fork Little Beaver Creek, Little Beaver Creek and the Ohio River.

The plaintiffs had not returned to their homes by Thursday and "are faced with the prospect that the real and personal property they own may be damaged beyond their lifetimes and is now worth far less and might be or become unsaleable," according to the lawsuit.

They are seeking monetary damages for "economic and non-economic damages" among other various fees and court costs.

This article originally appeared on The Repository: Lawsuit claims fish, animals dying 20 miles away from East Palestine

How dangerous train derailments affect communities like East Palestine, Ohio

Caitlin Dickson and Christopher Wilson

Sat, February 18, 2023

A woman takes a photo of a train that derailed in Sandusky, Ohio, in October 2022. (Gina Bates/Facebook)

Four months before a Norfolk Southern train carrying toxic chemicals ran off the tracks in East Palestine, Ohio, creating a fiery explosion that burned for days, another cargo train operated by the same company derailed at an overpass roughly 140 miles away, in Sandusky, Ohio.

Fortunately, no one was injured as a result of the Sandusky derailment, which caused several rail cars to overturn and fall onto one of the main roads leading in and out of the city. The train had been hauling paraffin wax, some of which leaked from the derailed cars and into the city’s sewers, but it quickly hardened and reportedly posed no danger, according to city officials. Roughly 1,500 people were temporarily left without power after the crash, and Amtrak was forced to reroute many of its trains while railroad workers rushed to repair the line. Although the railroad was back up and running a week later, the underpass below remained closed to vehicles and pedestrians for months.

Days after the derailment, a prescient editorial in the Sandusky Register called for a thorough and transparent investigation into the derailment, arguing that “knowing full well the cause for what happened is the first, most important step in preventing it from happening again.”

“It could have been catastrophic, but, fortunately, the loss of life and serious injury both were avoided if only by luck,” the Register’s editorial board wrote. “But the next time, if something like this happens again, it could be more devastating, and someone could be hurt or killed. It seems like pure luck everyone escaped safely this time.”

Sandusky wasn’t the only city in Ohio to experience a train derailment in the months leading up to the crash in East Palestine. In early November, 22 cars of a 237-car train transporting rock salt and other materials derailed in Ravenna Township, a municipality of fewer than 9,000 people roughly 20 miles east of Akron. Days later, another train carrying garbage derailed between Toronto and Steubenville, dumping garbage into the Ohio River. Both of those trains also belonged to Norfolk Southern, one of the nation’s largest railroad companies.

A handwritten sign outside a flower shop on Market Street on Feb. 14 in East Palestine. (Angelo Merendino/Getty Images)

According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics and the Federal Railroad Administration, there were an average of 1,705 train derailments per year in the U.S. between 1990 and 2021. A number of derailments have already been reported in various other parts of the country this year, and even in the weeks since the crash in East Palestine.

For the most part, these incidents don’t result in death, injury or the release of hazardous substances into the nearby community — which is why they don’t usually receive more than a blurb in the local news.

But they nevertheless have a real impact on the often small, working-class communities where they tend to take place.

“This is the cost of doing business. It's just that these costs are being externalized mostly to these very small communities that are becoming victimized by these catastrophes,” said Anne Junod, a senior research associate at the Washington, D.C.-based Urban Institute who has studied catastrophic train derailments at Ohio State. “If you look at most of the derailments that have occurred in the last 15 years, because of this expansion in oil and gas development, these are happening in our smallest communities, for the most part, that are the least capitalized to do anything about it.”

In an interview with Yahoo News, Junod said she was much less surprised to learn of the derailment in East Palestine than she was by the amount of media attention it has received in the weeks since.

“Frankly, … this accident wasn't a surprise at all; these accidents have been happening for quite a while,” she said. “I'm glad to see it getting its due attention, because it's been affecting communities across North America for the better part of the last 15 years.”

But while national interest in East Palestine has cast a welcome spotlight on some of the very real issues that have long plagued communities along freight rail lines, Junod warned that unless the current attention leads to meaningful policy changes, these kinds of events are certain to continue.

“My hope is thin that we’ll see a lot of changes coming out of this, just because this is another in a long line of these derailments,” she said.

Despite the apparent frequency of derailments in general, trains are still considered the safest way to transport large volumes of chemicals over long distances, according to the Federal Railroad Administration. But while train wrecks involving hazardous materials are relatively uncommon, according to an analysis from USA Today, federal inspectors have flagged 36% more hazmat violations over the last five years than in the five years before that.

Rail companies in recent years have turned to Precision Scheduled Railroading, a system intended to maximize efficiency that results in longer, heavier trains. It has also resulted in a reduction in the number of workers, which railroad unions say has resulted in more cursory inspections and trains that are less safe.

There has also been a rollback on a new braking system. In 2015, the Obama administration instituted new rules on the transportation of crude oil, which were criticized for not being rigorous enough. Under former President Donald Trump, numerous regulations were rolled back, including one mandating the use of electronically controlled pneumatic (ECP) brakes, stating that it was too costly. The Associated Press found that Trump’s administration had miscalculated its estimates. Norfolk Southern said that it had “opposed additional speed limitations and requiring ECP brakes” in a 2015 lobbying disclosure.

An air monitoring device is fixed to a pole after the derailment in East Palestine. (Reuters/Alan Freed)

As for potential changes that could reduce the number of derailments, Junod suggested updating the braking system and legislating an increase in staffing that would allow for larger crews, more thorough inspections and additional time for maintenance.

“If you have one-person crews, if you have archaic braking systems, and you have unworkable maintenance expectations, you're going to see these types of accidents. And that's why we're seeing them,” Junod said.

Some state and federal officials have raised the possibility of regulatory changes in the wake of the East Palestine derailment, but so far they’ve mostly focused on rules that would require the railroad to notify local officials in advance about trains carrying hazardous materials.

In a fact sheet released Friday, the White House said Biden’s Department of Transportation was “working on rulemakings to improve rail safety including proposing a rule that would require a minimum of a two-person train crew size for safety reasons” and “developing a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that will require railroads to provide real-time information on the contents of tank cars to authorized emergency response officials responding to or investigating an incident involving the transportation of hazardous materials by rail.”

The East Palestine derailment has also broached questions about who should be responsible for handling the response to these incidents, and whether railroad companies can be trusted to prioritize public health and safety over their own financial interests.

A burned container at the site of the East Palestine train derailment.

(Reuters/Alan Freed)

Norfolk Southern’s response in East Palestine has been criticized by residents and officials in both state and federal governments. Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro expressed “serious concerns” on Tuesday, accusing the company of having been unwilling to explore alternative courses of action, “including some that may have kept the rail line closed longer but could have resulted in a safer overall approach for first responders, residents, and the environment." The EPA said earlier this week that Norfolk Southern failed to properly dispose of contaminated soil at the crash site in its effort to get the railway reopened.

In an email to Yahoo News earlier this week, a spokesperson for Norfolk Southern said the company has “called the governor to address his concerns,” and insisted that it is “committed to ensuring health and safety through ongoing environmental monitoring and support for their needs.”

“Norfolk Southern was on-scene immediately following the derailment and began working directly with local, state, and federal officials as they arrived at the unified command established in East Palestine by local officials, including those from Pennsylvania,” the company said. “We remain at the command post today working alongside those agencies to keep information flowing from our teams working at the site.”

Reports from East Palestine this week revealed the community's skepticism and mistrust of the controlled burn of chemicals from the derailed cars. Despite repeated assurances from state officials that it was now safe for residents who had been forced to evacuate during the burn to return to their homes, many locals continued to report rashes, headaches and difficulty breathing, as well as an odd smell in the air.

“We've been let down,” one local woman told EPA Administrator Michael Regan, who met with residents in East Palestine on Thursday as EPA officials conducted tests of the water and air at their homes. “My community should not have been back before that was done.”

Norfolk Southern’s response in East Palestine has been criticized by residents and officials in both state and federal governments. Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro expressed “serious concerns” on Tuesday, accusing the company of having been unwilling to explore alternative courses of action, “including some that may have kept the rail line closed longer but could have resulted in a safer overall approach for first responders, residents, and the environment." The EPA said earlier this week that Norfolk Southern failed to properly dispose of contaminated soil at the crash site in its effort to get the railway reopened.

In an email to Yahoo News earlier this week, a spokesperson for Norfolk Southern said the company has “called the governor to address his concerns,” and insisted that it is “committed to ensuring health and safety through ongoing environmental monitoring and support for their needs.”

“Norfolk Southern was on-scene immediately following the derailment and began working directly with local, state, and federal officials as they arrived at the unified command established in East Palestine by local officials, including those from Pennsylvania,” the company said. “We remain at the command post today working alongside those agencies to keep information flowing from our teams working at the site.”

Reports from East Palestine this week revealed the community's skepticism and mistrust of the controlled burn of chemicals from the derailed cars. Despite repeated assurances from state officials that it was now safe for residents who had been forced to evacuate during the burn to return to their homes, many locals continued to report rashes, headaches and difficulty breathing, as well as an odd smell in the air.

“We've been let down,” one local woman told EPA Administrator Michael Regan, who met with residents in East Palestine on Thursday as EPA officials conducted tests of the water and air at their homes. “My community should not have been back before that was done.”

Rail employees navigate debris and toppled hopper cars in 2012 at the scene of the derailment at the Main Street overpass in Ellicott City, Md.

(Karl Merton Ferron/Baltimore Sun/Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

Junod noted that even if the cleanup occurs and residents receive financial compensation, long-term psychological trauma will persist after an incident like the one in East Palestine, which she described as “fundamentally [changing] this community for the people that live there.” She cited a 2013 train accident that killed 47 people in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec. Six years after the crash and explosion, a study from the regional public health authority showed that while residents had been improving, seven out of 10 adults "still showed signs of post-traumatic stress,” and that at least two suicides had been linked to the accident.

“People are incredibly distressed, and there are effects we see over the long-term years from now in other communities that have experienced this type of catastrophe,” Junod said. “You see PTSD, you see depression, you see anxiety at levels that didn't exist before.”

Meanwhile, on the other side of the state, city officials in Sandusky announced this week that the underpass closed off since the train derailment in October was now partially reopened to northbound traffic, with a 15 mph speed limit.

In interviews with local news outlets, the city’s director of public works hailed this as a sign of progress, after months of frustration. But public comments posted to the city of Sandusky’s Facebook page in response to the announcement on Thursday revealed a mix of relief, skepticism and fear from local residents, especially in light of recent events.

“Hey, they could have had hazardous cargo,” wrote one person. “Consider ourselves lucky.”

Junod noted that even if the cleanup occurs and residents receive financial compensation, long-term psychological trauma will persist after an incident like the one in East Palestine, which she described as “fundamentally [changing] this community for the people that live there.” She cited a 2013 train accident that killed 47 people in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec. Six years after the crash and explosion, a study from the regional public health authority showed that while residents had been improving, seven out of 10 adults "still showed signs of post-traumatic stress,” and that at least two suicides had been linked to the accident.

“People are incredibly distressed, and there are effects we see over the long-term years from now in other communities that have experienced this type of catastrophe,” Junod said. “You see PTSD, you see depression, you see anxiety at levels that didn't exist before.”

Meanwhile, on the other side of the state, city officials in Sandusky announced this week that the underpass closed off since the train derailment in October was now partially reopened to northbound traffic, with a 15 mph speed limit.

In interviews with local news outlets, the city’s director of public works hailed this as a sign of progress, after months of frustration. But public comments posted to the city of Sandusky’s Facebook page in response to the announcement on Thursday revealed a mix of relief, skepticism and fear from local residents, especially in light of recent events.

“Hey, they could have had hazardous cargo,” wrote one person. “Consider ourselves lucky.”