Timothy J. Heaphy Led the House Jan. 6 Investigation. Here's What He Learned.

Luke Broadwater

Sun, February 19, 2023

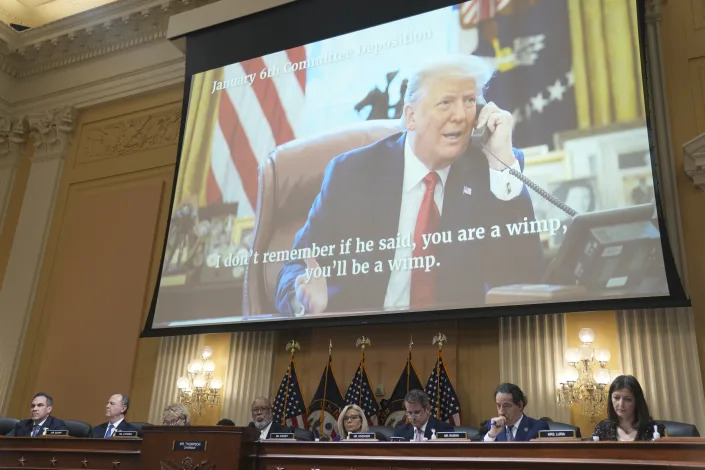

The House committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol meets in Washington on Dec. 19, 2022. (Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times)

WASHINGTON — Timothy J. Heaphy, the former U.S. attorney who served as the top staff investigator for the special House committee that scrutinized the Jan. 6, 2021, Capitol attack, knew going in that the inquiry would be important.

But it was not until he and his team, including about a dozen former federal prosecutors, began digging into the evidence that he realized the panel would break new ground, as it became clear to him that former President Donald Trump had directed a “multipart plan to prevent the transfer of power.”

During the panel’s 18-month investigation, Heaphy, 59, declined interview requests, but he is now ready to speak out about the panel’s work and its findings.

In a wide-ranging interview with The New York Times, Heaphy made the case for why the Justice Department should charge Trump and his allies with crimes and discussed intelligence failures in the lead-up to Jan. 6. He also said that leaks had hindered the panel’s investigation and spoke of how the committee explored measures to compel testimony from recalcitrant witnesses that might have included locking them up.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How did you get involved with the Jan. 6 committee?

A: I had done a similar report about the Charlottesville [Virginia] protests. I live in Charlottesville, and the city hired me and a team to do an independent review of how the city handled those events. Fast forward five years when the riot at the Capitol happened, I figured there was going to be a similar after-action review. I expressed interest and was hired to be the chief investigative counsel.

Q: Most congressional committees are lucky to have one former federal prosecutor on staff, but the Jan. 6 committee hired more than a dozen. Why was that important to the panel’s strategy?

A: There were 14. Because of the magnitude of the work, we’re fortunate that it drew that kind of talent. We knew this was not a typical congressional investigation. This was going to be faster paced, more contentious. It felt very similar to a grand jury investigation.

Q: What was the moment when you this committee would be breaking new ground?

A: When the pattern of the multipart plan to prevent the transfer of power started to take shape. That started to fall into place pretty early, and that was surprising. The world had seen the violence of the Capitol and how awful it was. But how we got there, and how methodical and intentional it was — this ratcheting up of pressure that ultimately culminates in the president inciting a mob to disrupt the joint session — that was new.

Q: How early on did you know you had enough material for a criminal referral?

A: When we started to see intentional conduct, specific steps that appear to be designed to disrupt the joint session of Congress, that’s where it starts to sound criminal. The whole key for the special counsel is intent. The more evidence that we saw of the president’s intent, and others working with him, to take steps — without basis in fact or law — to prevent the transfer of power from happening, it started to feel more and more like possible criminal conduct.

Q: For those on your staff who were new to Capitol Hill, how did they adjust to the culture of Congress, where politics and politicians run everything?

A: The Hill is a different culture than the Department of Justice. A grand jury explicitly is a secret process. And it doesn’t help an investigation when every step you take is reported. I mean, there were days when we would interview a witness and literally 30 minutes later, there’s Luke Broadwater on TV saying the select committee interviewed the witness. And that makes it really difficult because there were times when people would say, “Well, my client would like to help the committee, but she’s concerned that if she does, then she’ll immediately be outed as a turncoat.” So the public nature, the scrutiny under which we operated, was not helpful, and it made it more difficult for us to earn the trust and confidence of people.

Q: The committee’s summer hearings were widely hailed as a success because of both their evidentiary and production value. What do you attribute that to?

A: Hearings is not the right word for what we did. We called them hearings, but they were presentations more than hearings.

The communications strategy was different than anything I’ve ever done in the grand jury and anything that had been done in Congress. When I started this job, I read the 9/11 Commission Report and I met with its author, Philip Zelikow, because he lives in Charlottesville. I looked at that as the gold standard. But it was pretty obvious to us really early that we can’t just write a long report that you buy at Barnes & Noble. America is different now. So we needed to find ways to present our findings more visually, in shorter chunks, in a social media-fueled information landscape.

The committee hired James Goldston, who’s the former president of ABC [News], and he brought in a bunch of producers. So there was this collaboration of lawyers and producers. That was a combination of skills that I don’t know if Congress had seen before.

I’m really glad that all of our transcripts have been released. So if anyone thinks that we misled or shaded or hid facts, it’s all out there. I wanted to make sure as the chief investigator that every single statement that any member made, that any witness made, we could stand behind.

Q: There has been some criticism of the committee’s final report. Some have said law enforcement failures were not included to the full extent possible, and others say social media companies’ failures were not included to the extent they could have been. Your response?

A: First of all, all of the transcripts and all of the documents that are at least cited in the report were made public. The report could not include every single fact. Again, these are hard decisions about what’s in the report and what isn’t. I think the law enforcement story is very carefully detailed in the two appendices to the report. Social media doesn’t have its own stand-alone appendix, but we didn’t hide the important context of the social media landscape and algorithms and how social media companies didn’t moderate content enough.

That said, those are contextual factors that do not, in the committee’s view, in my personal view, take away from the core responsibility for Jan. 6, which is the president and his co-conspirators.

Q: You recently started a Twitter account, it seems, to push back on the narrative that law enforcement failures are to blame for the Capitol attack. Why?

A: Law enforcement had specific intelligence about potential violence directed at the joint session of Congress, and didn’t accurately assess and operationalize that. But some people have mischaracterized that as me saying that it’s law enforcement’s fault, that law enforcement could have prevented this or that the congressional leadership should have. That’s just wrong.

It is certainly not the congressional leadership’s fault that law enforcement didn’t accurately assess intelligence. [Former Capitol Police] Chief [Steven] Sund told the speaker’s staff on Jan. 5: We’re ready for this. Congressional leadership of both parties were assured that this was in hand.

There’s going be a lot of people here, but we are prepared — that was wrong, obviously.

Q: You made criminal referrals against Donald Trump. Other people were cited in the report’s section for those referrals, including lawyers John Eastman and Jeffrey Clark. Who do you think should be charged?

A: There’s evidence that the specific intent to disrupt the joint session extends beyond President Trump. There is a cast of characters that includes the ones you mentioned. I think you could look at [Rudy] Giuliani, and Mark Meadows. I think that the Justice Department has to look very closely at whether there was an agreement or conspiracy.

But there’s a lot of evidence that we didn’t get. Mr. Meadows didn’t come and talk to us. We did interview Mr. Giuliani, but he asserted attorney-client privilege a lot. John Eastman cited the Fifth Amendment to everything. So a lot of that decision by Justice will depend upon their ability to go beyond what we did. A criminal grand jury investigation arguably overrules or takes precedence over an attorney-client privilege assertion or executive privilege. The grand jury may be able to get answers that we didn’t get, and I hope that they do. How broad the conspiracy extends, I don’t know. But it’s potentially broader than even the people that we mentioned.

Q: For a while your investigation, by my estimation, seemed to be ahead of the Justice Department’s. Do you think the Justice Department is now beginning to overtake your work?

A: I hope so. I think you’re right that we were probably ahead of them on election stuff, but they were ahead of us on the rioters and seditious conspiracy.

I think our hearings got their attention, and they started to catch up. There was a point around the beginning of our hearings, where they wrote a letter asking us for all transcripts. That was a big change. They finally assigned some prosecutors and some resources to look at the broader context, not just violence at the Capitol.

Q: One criticism of the committee’s investigation is the panel waited until near the end of its work to issue a subpoena to Trump and never issued a subpoena to Vice President Mike Pence. Why didn’t you issue those subpoenas early on?

A: In any investigation, you want to learn as much as you can before you get to the most significant witnesses. Much like you do in a criminal investigation, you climb the ladder. You talk to people of increasing significance. You start at the bottom, and you build a foundation.

Q: I understand there was, at some point, preliminary talk about invoking Congress’ old inherent contempt powers that allow the House to arrest people. How close did the committee come to doing that?

A: I can’t get into specific internal discussions, but I will say that the committee was frustrated with certain witnesses’ refusal to cooperate or even engage with the committee at all. And that led to creative thinking about what are our options here.

Q: What one witness do you wish you could have gotten more out of?

A: There were several witnesses who I found extremely credible, but who made privilege assertions, including Marc Short and Pat Cipollone. I would say they were both very centrally involved in the events and were present for direct communications with the president and the vice president. They were not willing to share with us those conversations. If they had not drawn those lines, they could have recounted direct meetings and conversations that could have been really important. We kept coming back to the same core issue of intent. What did the president know? What were his intentions?

Q: What do you think is the main lesson of the Jan. 6 committee?

A: My main takeaway is how close we came. I grew up believing that our democratic systems are durable. I didn’t fully appreciate sometimes how fragile democracy is. But for the courage of a handful of people who elevated principle over politics, against their own self-interest, we could have had a different outcome. We could have had the will of the people subverted. That’s frightening, and we can’t take it for granted.

© 2023 The New York Times Company