How some Muslim and non-Muslim rappers alike embrace Islam’s greeting of peace

In many parts of the world, hip-hop has become a way for Muslim artists to assert their belonging and identity.

(The Conversation) — Ever since the United States’ “war on terror” began, American media has been rife with stereotypes of Muslims as violent, foreign threats. Advocates trying to push back against this characterization sometimes emphasize that “Islam means peace,” since the two words are derived from the same Arabic root.

Indeed, the traditional Muslim greeting “al-salamu alaykum” means “peace be upon you.” Some Americans were already familiar with the phrase, thanks to an unexpected source: hip-hop culture, which often incorporated the Arabic phrase.

This is but one example of Islam’s deep intertwining with the threads of hip-hop culture. In her groundbreaking book “Muslim Cool,” scholar, artist and activist Suad Abdul Khabeer shows how Islam, specifically Black Islam, was a crucial part of hip-hop’s roots – asserting the faith’s place in American life. From prayerlike lyrics to tongue-in-cheek references, Islam and other religions are woven into hip-hop’s beats.

That’s the focus of a class we teach at Boston University. One of us is a professor of religion, history and pop culture, while the other is a graduate student in Islamic Studies.

More than ‘hello’

In Muslim cultures, “al-salamu alaykum” is more than a way of saying hello. It points to the spiritual peace of submitting to God – and not only in this life. Saying “peace be upon you” is a prayer that God will grant heaven to the person with whom you are speaking. Many Muslims believe that “salam” is also the greeting heard upon entering heaven.

The Quran instructs Muslims that “when you are greeted with a greeting, respond with a better greeting or return it.” This means that the proper response to “al-salamu alaykum” is, at a minimum, to respond in kind: “wa alaykum al-salam.”

This exchange has been adapted by several rap artists – including Rick Ross, who does not identify as Muslim, and turns the phrase’s meaning on its head. Ross uses the greeting in the hook of his song “By Any Means,” referencing a famous speech by civil rights leader Malcolm X, who was a minister of the Nation of Islam for many years until shortly before his assassination. In 1964, Malcolm X declared African Americans’ right “to be respected as a human being … by any means necessary.”

Half a century later, Ross rapped,

By any means, if you like it or not

Malcolm X, by any means

Mini-14 stuffed in my denim jeans

Al-salaam alaykum, wa alaykum al-salaam

Whatever your religion kiss the ring on the Don

Ross’s use of the phrase, right after he mentions Malcolm X, appears to insinuate that if one wishes him peace, he will wish them the same. However, if one wishes him violence, he will not hesitate to respond in kind.

‘Peace to all my shorties’

Other hip-hop artists have used “al-salamu alaykum” in many different ways, including lyrics that show broader familiarity with the laws of Islam. For example, it is sometimes contrasted with pork, which is prohibited in Islam, and by extension, the police – the “pigs,” in derogatory slang – though it is more common for non-Muslim singers to use it in this way.

“Tell the pigs I say Asalamu alaikum,” Lil Wayne says in “Tapout,” a song that has little else to do with Islam. Joyner Lucas likewise raps, “I say As-salāmu ʿalaykum when I tear apart some bacon,” in the song “Stranger Things.” Combinations of the sacred and the profane are present throughout hip-hop, not limited to references to Islam.

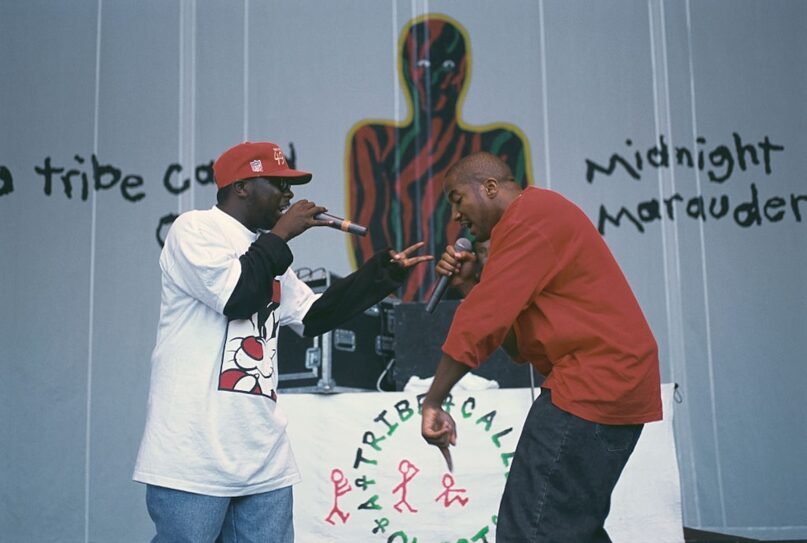

Finally, many rappers, particularly those who are Muslim, use the greeting in a more straightforward manner. In their 1995 song “Glamour and Glitz,” A Tribe Called Quest raps:

Peace to all my shorties who be dying too young

Peace to both coasts and the land in between

Peace to your man if you're doing your thing

Peace to my peoples who is incarcerated

Asalaam alaikum means peace, don't debate it

Here they affirm and assert that the core of the greeting is one of peace and harmony – not only between people, but between all of God’s creations.

Shared identity

French Montana performs during the premiere of ‘For Khadija,’ a documentary about his family, at the 2023 Tribeca Festival.

Arturo Holmes/Getty Images for Tribeca Festival

But even if Muslims come in peace, society may not see them that way – and that experience of discrimination often comes through in some lyrics. Rapper French Montana, who immigrated to the Bronx – the birthplace of hip-hop – from Morocco, raps in his 2019 song “Salam Alaykum:”

As-salamu alaykum,

That pressure don’t break,

It don’t matter what you do,

they still gon’ hate you

It’s a harsh recognition that whatever one’s actions, whether violent or peaceful, they may still result in racism – a realization he shares with some fellow Muslim rappers in Europe. A comedic take on this is done by Zuna and Nimo in their 2016 song “Hol’ mir dein Cousin,” where at the start of the song, Nimo states he has a shipment of “haze–” marijuana, but at the end of the video, it turns out the shipment is of “Hase–” bunnies. Yet, throughout the song the rappers speak about violence and drug trade, painting a conflicting picture of innocence versus guilt.

Fatima El-Tayeb, a scholar of race and gender, calls hip-hop a “diasporic lingua franca” in her 2011 book “European Others,” highlighting how an art form created by African Americans, and speaking to their experiences, has become one of the main ways minorities around the world speak about their struggles and successes. Some young Muslims in Europe, for example, use hip-hop as a key way to assert their sense of belonging in societies.

In hip-hop, “al-salamu alaykum” is not treated as though it were part of a foreign culture. These rappers’ beats create a space where it’s OK to be Muslim – a space in which Islam is not merely tolerated, but recognized as a valuable part of pop culture.

(Margarita Guillory, Associate Professor of Religion, Boston University. Jeta Luboteni, Ph.D. Student in Religion, Boston University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)