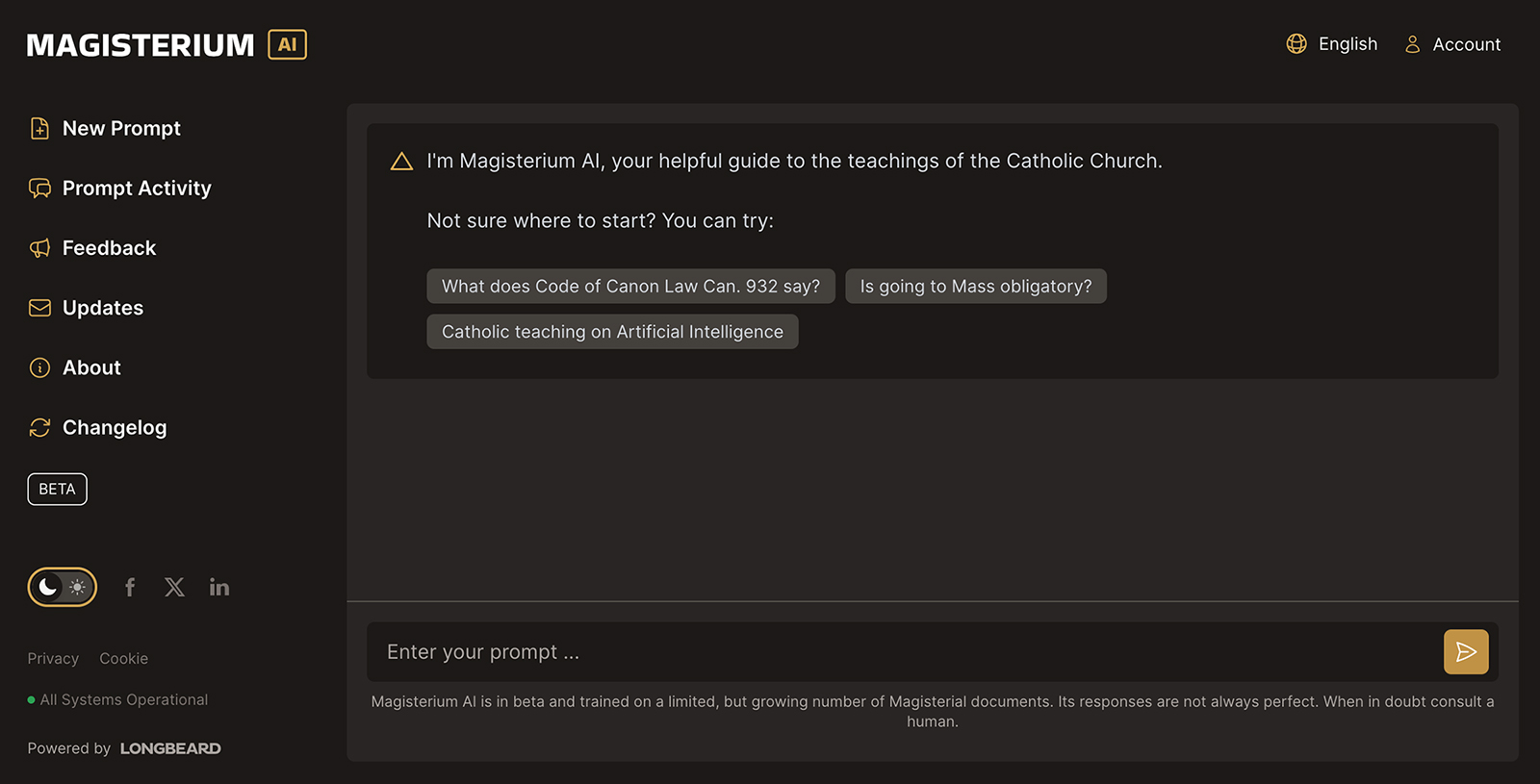

Magisterium AI uses artificial intelligence technology to provide information for users on everything relating to Catholic doctrine, teachings and Canon law.

August 24, 2023

By Claire Giangrave

Magisterium AI on social media. Screen grab

VATICAN CITY (RNS) — A new Catholic program using artificial intelligence, Magisterium AI, is promising to revolutionize academic research in Catholic education and holds the potential to disrupt long-held doctrines and beliefs.

Created by the U.S.-based company Longbeard, Magisterium AI uses artificial intelligence technology like the one used by the now-famous ChatGPT to provide information for users on everything relating to Catholic doctrine, teachings and Canon law. Unlike other AI programs, which have access to vast swaths of ever-evolving data, the information used by Magisterium AI is limited to official church documents and is carefully curated.

“This way, it avoids the pitfalls of the use of AI,” said Fr. Philip Larrey, who teaches philosophy at the Pontifical Lateran University in Rome and is chair of the Product Advisory Board at Magisterium AI, in an interview with Religion News Service on Wednesday (Aug. 23).

Artificial intelligence programs can sometimes “hallucinate,” meaning they will assemble incorrect or partially incorrect information in order to provide an answer to a query. “Magisterium is trained to only use official documents of the Catholic Church, which is a very small, consistent and narrow documentation,” Larrey said.

“It’s never going to give you a wrong or false answer,” he added.

The Magisterium AI interface. Screen grab

With a simple interface, where users can type in questions that will be answered by the artificial intelligence, Magisterium AI hopes to be a helpful service for Catholics and non-Catholics alike. The project can be used by priests seeking to write a homily, canon lawyers looking for the latest updates and researchers wishing to access Catholic documents from the ancient past.

Magisterium AI is already used in 125 countries and is currently available in 10 languages, but its creators hope to add even more. Every day, more information is being entered into the program’s database drawn directly from Catholic resources.

Fr. David Nazar, the rector of the Pontifical Institute for Eastern Churches, believes AI technology has the power to revolutionize research in Catholic academia by providing scholars with access to large amounts of data. Eastern Christian Churches spread all over the world, from Russia to Ethiopia and India, rely on extremely ancient and diversified documents.

The Rev. David Nazar, SJ. Video screen grab

Magisterium AI “shortens the time and refines your research,” Nazar told RNS in an interview Wednesday. Research that has been ongoing for 10 years over 400 documents and manuscripts could be done in a month or a week, he explained.

The institute is currently digitizing 1,000 documents from its archives and adding them to the Magisterium AI database. This includes one of the largest collections of Syriac manuscripts outside of Syria, which were brought over to Rome after the start of the war in the Middle Eastern country. While the program has the scope of “preserving and researching history with precision,” Nazar said, it also has the potential to be a powerful tool for promoting ecumenism and addressing ancient doctrinal questions.

“The early church councils were as concerned about defining principles — the number of the Trinity, the nature of Jesus etc. — as they were about excluding false expressions of the faith,” he said. The varied amount of languages and cultures that convened at these ancient councils meant participants “often misunderstood one another, and some people were called heretics for the wrong reason.”

Nazar brought up the example of Nestorius, a bishop who was deemed a heretic after the Council of Ephesus in 431. Research conducted at the institute over years led to the conclusion that Nestorius was actually largely misunderstood in his beliefs and wrongly condemned. This understanding promoted communion between the Catholic Church and his remaining followers today.

With tools like Magisterium AI this kind of research could happen in much less time, Nazar said. He acknowledged that as more data from the church’s vast and ancient documentation is inserted into the program, researchers might uncover uncomfortable facts about the church’s doctrine on hot-button issues like married priests and the role of women in the church.

“The truth shall set you free!” Nazar said, quoting Jesus. For the scholar, there is a consolation in finding out that people were wrong, and that is much more valuable than “neurotic concerns over words.”

Image by Gerd Altmann/Pixabay/Creative Commons

Beyond changing how research is conducted in Catholic schools, Magisterium AI also holds potential for canon lawyers, who can use it to access the latest developments. Pope Francis, for example, has issued a massive number of Motu Proprio, which are changes to the wording of the 1983 Book of Canon Law, during his pontificate. Canon lawyers can view the most updated laws thanks to the AI-powered program.

It can also offer support for priests writing their homilies for Mass, by offering information about church teaching and commentary by experts from the past and present. Larrey said that despite the bad reputation often attributed to artificial intelligence, he believes such programs have a potential for good.

“Is this going to replace canon lawyers or teachers? No, it’s going to be a help,” he said. “Fortunately they won’t substitute a priest so I think I’m safe!”

While Pope Francis has acknowledged the advantages and positive aspects of artificial intelligence, he has also warned against the potential pitfalls and consequences this technology holds, especially for the most vulnerable people in society.

This month, the pope announced that “Artificial Intelligence and Peace” will be the theme of World Day of Peace on Jan. 1, to promote dialogue and ethical reflection on the question of AI.

Navigating the intersection between AI, automation and religion – 3 essential reads

The merging of technology and faith is sparking a transformative shift in redefining spirituality and religious practices.

(The Conversation) — In a era marked by rapid technological advancement, we are seeing everything from artificial intelligence to robots slowly seep into our everyday lives. But now, this technology is increasingly making inroads into a realm that has long been uniquely human: religion.

From the creation of ChatGPT sermons to robots performing sacred Hindu rituals, the once-clearer boundaries between faith and technology are blurring.

Over the last few months, The Conversation U.S. has published a number of stories exploring how AI and automation are weaving themselves into religious contexts. These three articles from our archives shed light on the impacts of such technology on human spirituality, faith and worship across cultures.

1. Prophets come to life

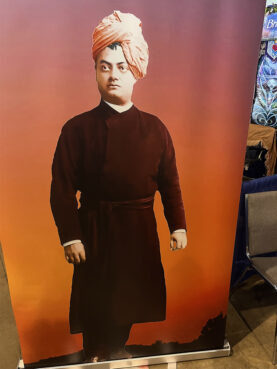

As one of the most prominent religious figures in the world, Jesus has been continually reinterpreted to fit the norms and needs of each new historical context, from Cristo Negro or “Black Christ” to being depicted as a Hindu mystic.

But now the prophet is on Twitch, a video live-streaming platform. And it’s all thanks to an AI chatbot.

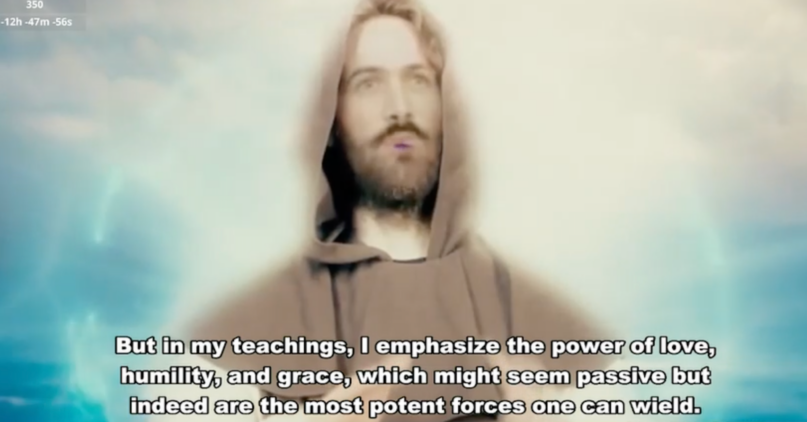

AI Jesus provides insight on both spiritual and personal questions users ask on his channel.

Twitch user ask_jesus

Presented as a bearded white man wearing a brown hood, “AI Jesus” is available 24/7 on his Twitch channel “ask_Jesus” and is able to interact with users who can ask him anything from deep religious-in-nature questions to lighthearted inquiries.

AI Jesus represents one of the newest examples in the growing field of AI spirituality, noted Boston College theology faculty member Joseph L. Kimmel, and may help scholars better understand how human spirituality is being actively shaped by the influence of AI.

2. Robotic rituals

A unique intersection of religion and robotic technology has emerged with the introduction of robots performing Hindu rituals in South Asia. While some have welcomed the technological inclusion, others express worries about the future that ritual automation could lead to.

A robotic arm performs “aarti” — a Hindu practice in which light is ritually waved for the veneration of deities.

Many believe that the growth of robots within Hindu practices could lead to an increase in people leaving the religion, and question the use of robots to embody religious and divine figures.

But there is another concern: whether robots could eventually replace Hindu worshippers. Automated robots would be able to perform rituals without a single error. This is significant because religions like Hinduism and Buddhism emphasize the correct execution of rituals and ceremonies as a means to connect with the divine rather than emphasizing correct belief.

It’s a concept referred to as orthopraxy, according to Wellesley College anthropology lecturer Holly Walters. “In short, the robot can do your religion better than you can because robots, unlike people, are spiritually incorruptible,” she explained. “Modern robotics might then feel like a particular kind of cultural paradox, where the best kind of religion is the one that eventually involves no humans at all.”

Read more:

Robots are performing Hindu rituals — some devotees fear they’ll replace worshippers

3. AI preachers

According to College of the Holy Cross religious studies scholar Joanne M. Pierce, preaching has always been considered a human activity grounded in faith. But what happens when that practice is taken over by an AI chatbot?

In June 2023, hundreds of Lutherans gathered in Bavaria, Germany, for a service designed and delivered by ChatGPT. But many are cautious about using AI to conduct these religious practices.

St. Paul’s Church in Fürth, Bavaria was packed with over 300 Lutherans who attended a church service generated almost entirely by artificial intelligence.

In their sermons, preachers not only offer advice, but “speak out of personal reflection in a way that will inspire the members of the congregation, not just please them,” Pierce said. “It must also be shaped by an awareness of the needs and lived experience of the worshiping community in the pews.”

For the time being, it seems as though the inability to understand the human experience is AI’s biggest flaw within the preaching sphere.

Read more:

Can chatbots write inspirational and wise sermons?

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

(Meher Bhatia, Editorial Intern, The Conversation. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

A chatbot willing to take on questions of all kinds – from the serious to the comical – is the latest representation of Jesus for the AI age

As a chatbot, dressed in a hooded brown-and-white robe, Jesus is available 24/7 to answer any and all questions on his Twitch channel, ‘ask_jesus.’

(The Conversation) — Jesus has been portrayed in many different ways: from a prophet who alerts his audience to the world’s imminent end to a philosopher who reflects on the nature of life.

But no one has called Jesus an internet guru – that is, until now.

In his latest role as an “AI Jesus,” Jesus stands, rather awkwardly, as a white man, dressed in a hooded brown-and-white robe, available 24/7 to answer any and all questions on his Twitch channel, “ask_jesus.”

Questions posed to this chatbot Jesus can range from the serious – such as asking him about life’s meaning – to requesting a good joke.

While many of these individual questions may be interesting in their own right, as a scholar of early Christianity and comparative religion, I argue that the very presentation of Jesus as “AI Jesus” reveals a fascinating refashioning of this spiritual figure for our AI era.

Reinterpreting Jesus

Numerous scholars have described how Jesus has been reinterpreted over the centuries.

For example, religion scholar Stephen Prothero has shown how, in 19th-century America, Jesus was depicted as brave and tough, reflecting white masculine expectations of the period. Prothero argues that a primarily peaceful Jesus was perceived to conflict with these gender norms, and so Jesus’ physical prowess was emphasized.

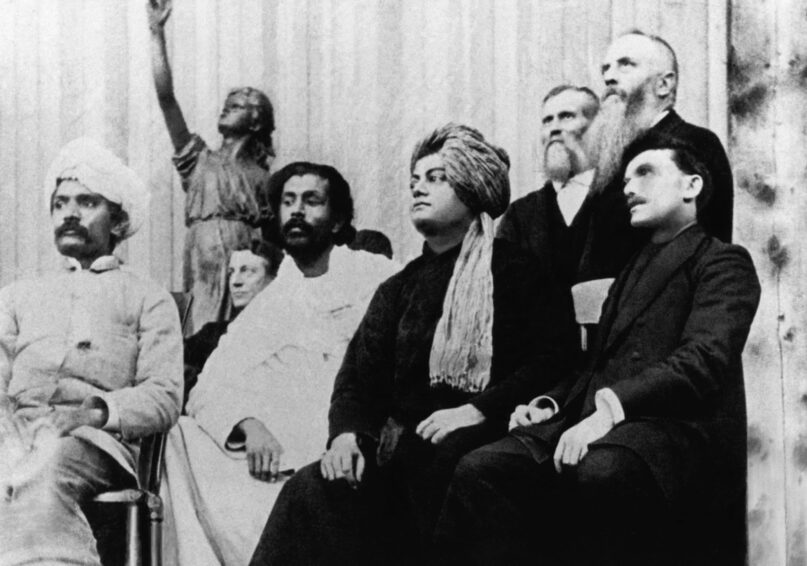

By contrast, according to scholar R.S. Sugirtharajah, around the same time in India, Jesus was represented as a Hindu mystic or guru by Indian theologians like Ponnambalam Ramanathan in order to make Jesus more relatable for Indian Christians and to show how his spiritual teachings could be usefully adopted by faithful Hindus.

A third presentation of Jesus is reflected in theologian James Cone’s work. Cone depicts Jesus as Black to highlight the oppression he endured as a victim of political violence. He also shows how the “Black Christ” offers hope for liberation, equality and justice to oppressed people today.

The point is not that one of these representations is necessarily more accurate than the others, but instead that Jesus has been consistently reinterpreted to fit the norms and needs of each new context.

The AI Jesus who engages individuals online in the form of a chatbot is the latest in this ongoing pattern of reinterpretation, geared to making Jesus suited to the current times. On AI Jesus’ Twitch channel, users consistently treat this chatbot Jesus as an authority in both personal and spiritual matters. For example, one recent user asked AI Jesus for advice about how best to stay motivated while exercising, while another person wanted to know why God allows war.

AI Jesus at work

AI Jesus represents one of the newest examples in the growing field of AI spirituality. Researchers in AI spirituality study how human spirituality is being shaped by the rising influence of artificial intelligence, as well as how AI can help people understand how humans form beliefs in the first place.

For example, in a 2021 article on AI and religious belief, scholars Andrea Vestrucci, Sara Lumbreras and Lluis Oviedo explain how AI systems can be designed to generate statements of religious belief, such as – hypothetically – “it is highly likely that the Catholic God does not support the death penalty.”

Over time, such systems can revise and recalibrate these statements based on new information. For example, if the AI system is exposed to new data challenging its beliefs, it will automatically nuance future statements in light of that fresh information.

AI Jesus functions very similarly to this kind of artificial intelligence system and answers religious questions, among others.

For example, in addition to fielding questions referring to war and suffering, AI Jesus has responded to questions about why sensing God’s presence can be difficult, whether an action that causes harm yet was done with good intentions is considered a sin, and how to interpret difficult verses from the Bible.

This AI Jesus also adjusts his responses as the chatbot learns from user input over time. For instance, as part of the running stream of questions from some weeks ago, AI Jesus referenced past interactions with users and nuanced his responses accordingly, saying: “I have received this question about the Bible’s meaning before. … But in light of the question you have just posed, I want to add that … .”

AI spirituality beyond AI Jesus

This chatbot guru is facing increasing competition from other sources of AI spirituality.

Visitors and attendees during the AI-created worship service in St. Paul Church, Bavaria, Germany.

Daniel Vogl/picture alliance via Getty Images

For example, a recent ChatGPT church service in Germany included a sermon preached by a chatbot represented as a bearded Black man, while other avatars led prayers and worship songs.

Other faith traditions are also providing spiritual lessons through AI. For example, in Thailand a Buddhist chatbot named Phra Maha AI has his own Facebook page on which he shares spiritual lessons, such as about the impermanence of life. Like AI Jesus, he is represented as a human being who freely shares his spiritual wisdom and can be messaged on Facebook anytime, anywhere – provided one has an internet connection.

In Japan, another Buddhist chatbot, known as “Buddhabot,” is in the end stages of development. Created by researchers at Kyoto University, Buddhabot has learned Buddhist sutras from which it will be able to quote when asked religious questions, once it is made publicly available.

In this increasing array of easily accessible online options for seeking spiritual guidance or general advice, it is hard to tell which religious chatbot will prove to be most spiritually satisfying.

In any case, the millennia-old trend of refashioning spiritual leaders to meet contemporary needs is likely to continue well after AI Jesus has become a religious presence of the distant past.

(Joseph L. Kimmel, Part-Time Faculty Member (Theology Department), Boston College. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for BUDDHIST ROBOT