Ideology Behind Gandhi’s Assassination Still Threatens His Rama Rajya

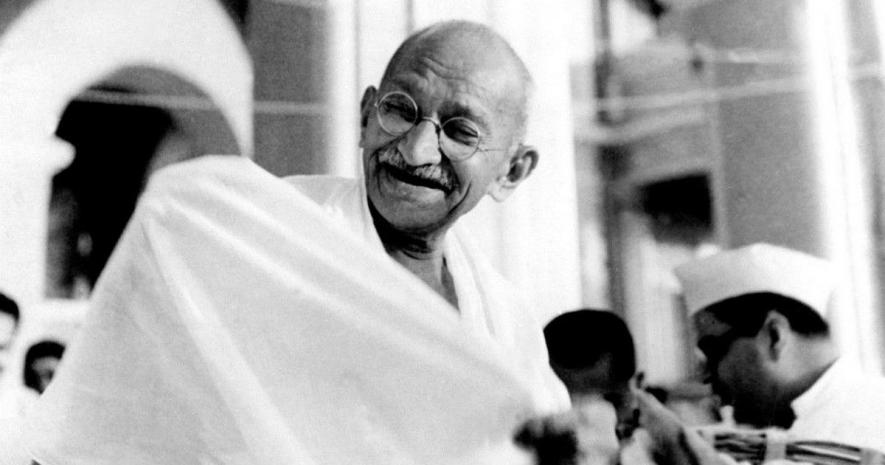

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The martyrdom of Mahatma Gandhi on 30 January 1948 was a grave tragedy for the nation, but India’s social fabric is still under threat from the continuing justification of that crime in myriad ways. One indicator is the recent developments regarding the Gyanvapi mosque in Varanasi and the Shahi Idgah in Mathura.

The majoritarian claims raised against these places of worship of Indian Muslims indicate that those who believe in an India divided along religious lines—who demolished the Babri mosque on 6 December 1992—are continuing with their divisive religious-political agenda. When the Babri mosque was demolished, the then Vice-President of India and Chairman of Rajya Sabha, KR Narayanan, said with deep anguish while presiding over the stormy proceedings of the House that the demolition represented the greatest tragedy India faced after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi.

Narayanan’s remarks drew a clear connection between two violent incidents that occurred nearly 45 years apart—they also suggested that the ideology that spurred both cataclysmic events was one and the same. His words got prominent space in the media of the time, and in 2019, the Supreme Court itself described the demolition of the mosque as an “egregious violation of the rule of law”. However, the “egregious” violations went unpunished even as the media refused to highlight the travesty of justice in the entire episode.

Had Gandhi Been Alive

Gandhi would have been hurt beyond measure to see people who razed the mosque raising ‘Jai Shri Ram’ chants as a cloak for their crime. He would have strongly disapproved of State association with the consecration of a temple at the site of the demolished mosque. Gandhi would have responded to the calls for recognition as temples of an ever-growing number of Muslim places of worship as equally unacceptable. Indeed, he would have found the participation of high constitutional functionaries of the State in the consecration ceremony on 22 January in Ayodhya inconsistent with Hinduism and the secular nature of the Indian State.

He who recited the name of Rama in Hindu shrines and Islamic places of worship alike, and who fell to three bullets fired by his assassin with a cry of ‘Hey Rama’, would have been at his wit’s end seeing the triumphalism of State functionaries at the consecration event, which negated their oaths to uphold India’s commitment to State secularism.

Rama Rajya, not Hindu Raj

On 22 January, at the consecration ceremony, some lines from Gandhi’s favourite hymn, “Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram”, were repeatedly played, but the words “Ishwar-Allah tero naam [You are known as Ishwar and Allah]” were omitted. The omission amounted to abandoning Gandhi’s belief in diverse approaches to divinity.

While Prime Minister Narendra Modi declared the arrival of Rama Rajya in India on that day, the entire event dismantled Gandhi’s idea of Rama Rajya. After all, Gandhi believed that Rama Rajya had nothing to do with a denominational State declaring the supremacy of the Hindu faith—held by the majority of Indians—over all other faiths. Almost a year before the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was established in 1925, Gandhi wrote in Young India on 31 July 1924, making it clear that the non-cooperation movement, a major component of freedom struggle, “...does not seek to establish Hindu Raj by the ‘grace of British Raj’, but it seeks to establish swaraj, meaning the government by the chosen representatives of the people in the place of the British Raj”.

In other words, even before the RSS or the Hindu Mahasabha existed, and their campaigns to create a theocratic Hindu Rashtra instead of a republic of India materialised, Gandhi unequivocally opposed the notion. He knew the dangers of defining India in terms of any one religion. That is why it is unfortunate that no constitutional functionary objected to the meaning of Gandhi’s beloved hymns being twisted at the consecration ceremony.

Gandhi’s Rama Rajya Opposed Majoritarianism

Rama Rajya, which Gandhi often talked about, had nothing to do with a theocratic state or a country governed along religious lines. His statement in 1924 that the non-cooperation movement did not seek to establish Hindu Raj should be juxtaposed with what he wrote about Rama Rajya in his journal, Navjivan, on 30 May 1920. He asserted in his write-up, titled Insanity, “If the king is mindful of the difficulties of the weakest section of his subjects, his rule would be Ramarajya; it would be people’s rule”. He also wrote, “We cannot expect this of any government in modern times, be it British or Indian, Christian, Muslim or Hindu”.

Gandhi was clear that Europe also “worships brute force or—which is the same thing—majority opinion, and the majority, surely, does not always look after the interests of the minority”. Exposing the inherent weakness of majority rule, Gandhi distinguished between majority and majoritarian rule, which could never promote the safety and security of all. He perceptively remarked, “In ordinary matters, the principle of majority rule is, by and large, justice as the world understands justice, but the purest justice can consist only in the welfare of all”.

Gandhi said, “It is only a government that fully protects the weakest among its subjects and safeguards all his rights, which may be described as perfectly democratic”. “Such a government,” he categorically said, “does not mean the rule of the majority, but protection of the interests of even the smallest limb of the realm”.

What Rama Rajya Symbolised

Gandhi, in 1920, summed up Rama Rajya as an idea that embraced the welfare of all from any community, especially the weakest. He did not expect the British ruling over India in 1920 to provide such a regime. His observations from more than a hundred years ago resonate in India now.

On 30 January 1948, Gandhi made the supreme sacrifice by laying down his life, considerably marginalising communal forces and their ideology. But they gained a fresh lease of life when the Rama temple-Babri masjid dispute got drawn into the mainstream of electoral politics. In this context, Gandhi’s worldview has greater significance today than ever.

The author served as Officer on Special Duty to President of India KR Narayanan. The views are personal.

LA REVUE GAUCHE - Left Comment: Search results for HINDUISM IS FASCISM