Members of far-right groups marching in Charlottesville, Virginia

Despite the popularity of the recent movie “Civil War,” we’re not on the verge of a second one. But we are separating into so-called “red” and “blue.” And if Trump is reelected president, he’ll hasten the separation.

Since the Supreme Court’s decision to reverse Roe v. Wade left the issue of abortion to the states, one out of three women of childbearing age now lives in a state that makes it nearly impossible to get an abortion.

And while red states are making it harder than ever to get abortions, they’re making it easier than ever to buy guns.

Red states are also banning diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives in education. Florida’s Board of Education recently prohibited public colleges from using state and federal funds for DEI. Texas Governor Greg Abbott has signed a law to require that all state-funded colleges and universities close their DEI offices.

Red states are suppressing votes. In Florida and Texas, teams of “election police” have been created to crack down on the rare crime of voter fraud, another fallout from Trump’s big lie.

They’re banning the teaching of America’s history of racism. They’re requiring transgender students to use bathrooms and join sports teams that reflect their sex at birth.

They’re making it harder to protest. More difficult to qualify for unemployment benefits and other forms of public assistance. Harder than ever to form labor unions.

They’re even passing “bounty” laws — enforced not by governments but by rewards to private citizens for filing lawsuits — on issues ranging from classroom speech to abortion to vaccination.

Blue states are moving in the opposite direction. Several, including Colorado and Vermont, are codifying a right to abortion. Some are helping cover abortion expenses for out-of-staters.

When Idaho proposed a ban on abortion that empowers relatives to sue anyone who helps terminate a pregnancy after six weeks, nearby Oregon approved $15 million to help cover the abortion expenses of patients from other states.

Maryland and Washington have expanded access and legal protections to out-of-state abortion patients. California has expanded access to abortion and protected abortion providers from out-of-state legal action.

After the governor of Texas ordered state agencies to investigate parents for child abuse if they provide certain medical treatments to their transgender children, California enacted a law making the state a refuge for transgender youths and their families.

Blue states are also coordinating more of their policies. During the pandemic, blue states joined together on policies that red states rejected — such as purchasing agreements for personal protective equipment, strategies for reopening businesses as Covid subsided, even on travel from other states with high levels of Covid.

But as blue and red states separate, what will happen to the poor in red states, disproportionately people of color?

“States’ rights” has always been a cover for racial discrimination and segregation. The poor — both white and people of color — are already especially burdened by anti-abortion legislation because they can’t afford travel to a blue state to get an abortion.

They’re also hurt by the failure of red states to expand Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act, by red state de facto segregation in public schools, and by red state measures to suppress votes.

One answer is for Democratic administrations and congresses in Washington to prioritize the needs of the red state poor and make extra efforts to protect the civil and political rights of people of color in red states. Yet the failure of the Senate to muster enough votes to pass the Freedom to Vote Act, let alone revive the Voting Rights Act, suggests how difficult this will be.

Blue states could spend additional resources on the needs of red state residents, such as Oregon is now doing for people from outside Oregon who seek abortions. And prohibit state funds from being spent in any state that bans abortions or discriminates on the basis of race, ethnicity, or gender.

California already bars anyone on a state payroll (including yours truly, who teaches at Berkeley) from getting reimbursed for travel to states that discriminate against LGBTQ+ people.

Where will all this end?

If Trump is elected this November, the separation will become even sharper. When he was president last time, Trump acted as if he was president only of the people who vote for him — overwhelmingly from red states — and not as the president of all of America.

Recall that during his presidency, he supported legislation that hurt voters in blue states — such as his tax law that stopped deductions of state and local taxes from federal income taxes.

More than 4 in 10 voters believe that a second civil war is likely within the next five years, according to a Rasmussen Reports poll conducted April 21-23.

Red zip codes are getting redder and blue zip codes, bluer. Of the nation’s total 3,143 counties, the number of super landslide counties — where a presidential candidate won at least 80 percent of the vote — jumped from 6 percent in 2004 to 22 percent in 2020.

Surveys show Americans find it increasingly important to live around people who share their political values. Animosity toward those in the opposing party is higher than at any time in living memory. Forty-two percent of registered voters believe Americans in the other party are “downright evil.”

Almost 40 percent would be upset at the prospect of their child marrying someone from the opposite party. Even before the 2020 election, when asked if violence would be justified if the other party won the election, 18.3 percent of Democrats and 13.8 percent of Republicans responded in the affirmative.

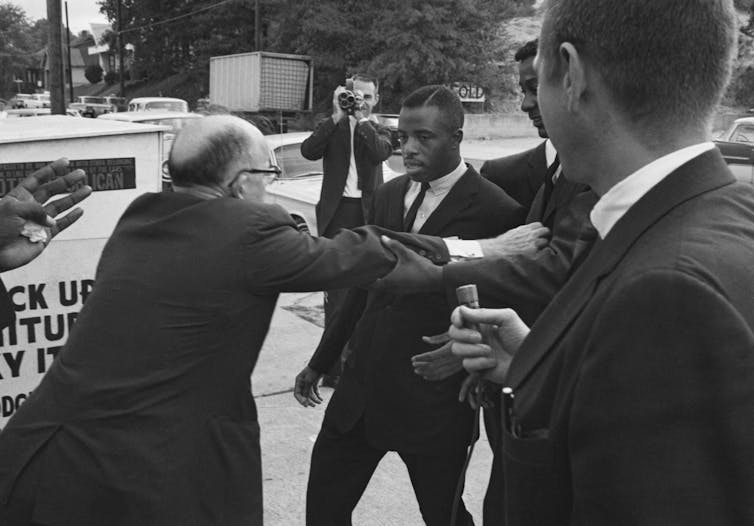

We are becoming two Americas — one largely urban, racially and ethnically diverse, and young. The other, largely rural or exurban, white and older.

But rather than civil war, I see a gradual, continuous separation — analogous to unhappily married people who don’t want to go through the trauma of a formal divorce.

America will still be America. But it is fast becoming two versions of America. The open question is the same as faced by couples who separate: Will the two remain civil toward each other?

Courtroom illustration depicting former President Donald Trump watching Michael Cohen's testimony

There is something important about Trump’s criminal trial in New York that’s not being openly talked about. I don’t mean we’re not getting the facts about what’s happening in Manhattan Superior Court. But something very big is being left out.

The trial has introduced us to a world of moral and ethical loathsomeness in which people use and abuse one another routinely. It’s Trump world.

Consider Stormy Daniels. Porn stars are entitled to do as they wish to make money. But when they extort their clients or boyfriends who are running for public office — demanding large payments in order to stay quiet about their affair — they’re violating public morality. They’re contributing to a society in which every interaction has a potential price.

Last week we heard Daniels’s story, even more detailed and lascivious than expected. But a troubling aspect of her behavior is that when Trump ran for office, she saw a chance to extort money from him. She then “shopped” her account of their sexual liaison, before finally accepting $130,000 to be silenced in the 2016 election’s final critical days.

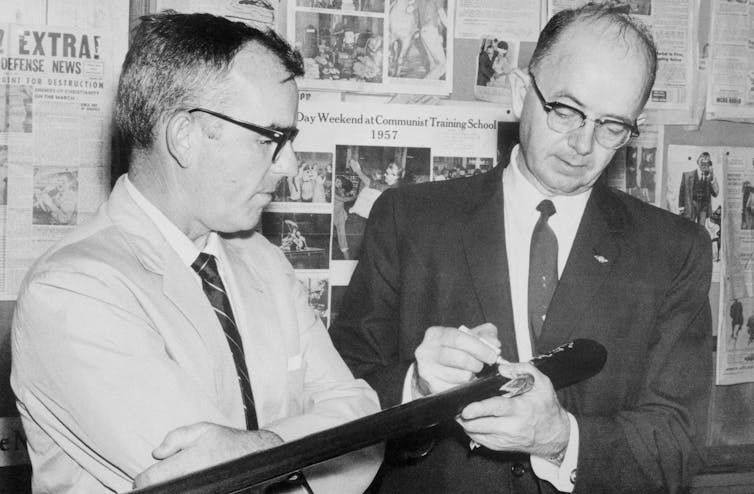

Or consider Michael Cohen. Powerful people often need “fixers” — assistants that carry out their wishes and protect them from legal or political trouble. But when those fixers arrange payments to keep stories out of the media, they’re treading on morally thin ice.

Cohen didn’t just fix. He boasted of burying Trump’s secrets and spreading Trump’s lies. In his work for Trump, he repeatedly acted illegally and found ways to cover up his actions. After he paid Daniels to keep silent and Trump was elected president, Cohen concocted with Trump a means of being reimbursed that involved falsifying records that disguised the repayment as ordinary legal expenses.

And then there’s David Pecker, publisher of the National Enquirer. Tabloids are part of a long tradition of American journalism. But when tabloid publishers buy stories to bury them on behalf of powerful people, thereby establishing a kind of bankable account of chits that can be cashed in with the powerful, it violates public morality because it corrupts our democracy.

Two weeks ago, Pecker testified about “catching and killing” stories — buying the exclusive rights to stories, or “catching them,” for the specific goal of ensuring the information never becomes public. That’s the “killing” part. According to people who have worked for him, Pecker mastered this technique — ethics be damned.

Which brings us to Trump himself. I don’t care that he had extramarital affairs. But when a presidential candidate tells his fixer to buy off someone — “Just take care of it” — so the public doesn’t get information before an election about a candidate that they might find relevant to evaluating him, it undermines democracy.

This cast of characters — and there are many, many others like them in Trump world — are loathsome not just because they have violated the law, but because they have contributed to creating a harsh society in which everyone is potentially bought or sold.

It’s a sell-or-tell society, a catch-and-kill society, a just-take-care-of-it society. A society where money and power are the only considerations. Where honor and integrity count for nothing.

I am not naive about how the world works. I’ve spent years in Washington, many of them around powerful people. I have seen the seamy side of American politics and business.

But the people who inhabit Trump world live in a more extreme place — where there are no norms, no standards of decency, no common good. There are only opportunities to make money off others and potential dangers of being ripped off by others.

It’s a place where there are no relationships, only transactions.

I sometimes worry that the daily dismal drone of Trump world — the continuous lies and vindictiveness that issue from Trump and his campaign, the dismissive and derogatory ways he deals with and talks about others, the people who testify at his criminal trial about what they have done for or to him and what he has done for or to them — have a subtly corrosive effect on our own world.

It’s important to remind ourselves that most of the people we know are not like this. That honor and integrity do count. That standards of decency guide most behavior. That relationships matter.

Robert Reich is a professor at Berkeley and was secretary of labor under Bill Clinton. You can find his writing at https://robertreich.substack.com/.