Monthly Review

23 June, 2024

[Editor’s note: LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal is sponsoring Ecosocialism 2024, which will be held June 28–30, Boorloo/Perth, Australia. For more information on the conference, including how you can participate online, visit ecosocialism.org.au.]

First published at Monthly Review.

The term Promethean, referring in this context to extreme productivism, first entered into the ecological debate as a censure aimed almost entirely at Karl Marx. It was adopted as a form of condemnation by first-stage ecosocialists in the 1980s and ’90s, who sought to graft standard liberal Green theory onto Marxism, while jettisoning what were then widely presumed to be Marx’s anti-ecological views. However, the Promethean myth with respect to Marx was to be subjected to a sustained attack, commencing twenty-five years ago, in the work of second-stage ecosocialists, represented by Paul Burkett’s Marx and Nature (Haymarket, 1999) and John Bellamy Foster’s “Marx’s Theory of Metabolic Rift” (American Journal of Sociology 105, no. 2 [September 1999])—followed soon after by Foster’s Marx’s Ecology (Monthly Review Press, 2000). Here it was understood that the outlook of classical historical materialism was not that of the promotion of production for its own sake—much less accumulation for its own sake—but rather the creation of a society of sustainable human development controlled by the associated producers. The key analytical basis of this recovery of the classical historical-materialist ecological critique was Marx’s theory of metabolic rift.

On the basis of the recovery of Marx’s deep-seated ecological critique, ecosocialism has made major advances over the last quarter-century. One notable work, in this respect, was Kohei Saito’s Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism (Monthly Review Press, 2017), which brought additional evidence to bear on the critique of the Promethean myth and on the development of Marx’s theory of metabolic rift. The result was the emergence of powerful ecological Marxist assessments of the contemporary planetary crisis provided by a host of thinkers, including such notable figures as Ian Angus, Jacopo Nicola Bergamo, Mauricio Betancourt, Brett Clark, Rebecca Clausen, Sean Creaven, Peter Dickens, Martin Empson, Michael Friedman, Nicolas Graham, Hannah Holleman, Michael A. Lebowitz, Stefano Longo, Fred Magdoff, Andreas Malm, Brian M. Napoletano, Ariel Salleh, Eamonn Slater, Carles Soriano, Pedro Urquijo, Rob Wallace, Del Weston, Victor Wallis, Richard York, and many others too numerous to name.

However, in the last couple of years, the myth of Prometheanism in Marx’s thought has been reintroduced in ghostly fashion by thinkers such as Saito, in his latest works, and by Jacobin authors Matt Huber and Leigh Phillips, representing two opposite extremes on the issue of the role of productive forces/technology. The result has been to erect a “Tower of Babel” that threatens to extinguish much that has been achieved by Marxian ecology.

In his two most recent studies, Marx in the Anthropocene (Cambridge University Press, 2023) and Slow Down (Astra Publishing House, 2024, originally titled Capital in the Anthropocene), Saito has gone back on his earlier contention in Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism that Marx was not a Promethean thinker, and now insists, drawing on the largely discredited work of the “analytical Marxist” G. A. Cohen, that Marx was a technological determinist for most of his life. The about-face by Saito on Marx and Prometheanism is clearly designed to accentuate what Saito now calls Marx’s “epistemological break,” beginning in 1868. From that point on, Marx is supposed to have entirely abandoned his previous historical materialism, rejecting all notions of the expansion of productive forces in favor of a steady-state economy, or degrowth. However, since there is not even the slightest textual evidence anywhere to be found in support of Saito’s claim on Marx and degrowth (beyond what has long been argued, that Marx was a theorist of sustainable human development), Saito is forced to read between the lines, imagining as he goes along. The thrust of his new thesis is that the “last Marx” concluded that the productive forces inherited from capitalism formed a trap, causing him to reject growth of productive forces altogether in favor of a no-growth path to communism. Such a view, however, is clearly anachronistic. Naturally, the fact that planned degrowth is a real issue today (see the special July–August 2023 issue of MR) does not mean that the problem would have presented itself in that way to Marx in 1868, in horse and buggy days, when industrial production was still confined to only a small corner of the world. (On Saito’s analysis, see Brian Napoletano, “Was Marx a Degrowth Communist?” in this issue.)

Ironically, Saito’s thesis that Marx was a Promethean up to and including the publication of Capital (viewed by Saito as a transitional work in this respect) receives strong backing from Huber and Phillips in their article “Kohei Saito’s ‘Start from Scratch’ Degrowth Communism” (Jacobin, March 9, 2024). Proudly holding up a “Promethean Marxism” banner, Huber and Phillips present themselves as belonging to a long tradition of well-known Prometheans, including not only Marx and Frederick Engels, but also V. I. Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and Joseph Stalin. For the Jacobin authors, for whom Marxism = Prometheanism, Saito is thus to be faulted not for suggesting that Marx was Promethean up until the writing of Capital, but rather for his claim that Marx jettisoned his Prometheanism in his white-beard years, failing to carry it all the way to his grave.

Although they adopt a Marxist cover, the views of Huber and Phillips on technology and the environment are virtually identical to those of Julian Simon, author of The Ultimate Resource (Princeton University Press, 1981) and the leading anti-environmentalist critic of the ecological limits to growth within the neoclassical-economic orthodoxy in the 1970s and ’80s (see Foster’s “Ecosocialism and Degrowth” in this issue). The Jacobin authors thus adopt a view that is not so much ecomodernist in orientation as a form of total human exemptionalism from ecological determinants, in which humanity is presumed to be able to transcend by technological means all Earth System limits—including those of life itself. The metabolic rift, we are told, does not exist since it is dependent on a rift in a nonexistent “balance of nature.” Here they ignore the fact that the notion of anthropogenic rifts in the biogeophysical cycles of life on the planet, raising the issue of mass extinction, extending even to human life itself, is central to modern Earth System science. It is not a question of a “balance of nature” as such, but rather one of preserving the earth as a safe home for humanity and innumerable other species.

Going against the current world scientific consensus, Huber and Phillips explicitly deny the reality of the nine planetary boundaries (climate change, biological integrity, biogeochemical cycles, ocean acidification, land system change, freshwater use, stratospheric ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol loading, and novel entities). Rather, they insist in their total exemptionalism that there are no biospheric limits to economic growth. Hence, “there is no need,” they tell us, “to move to a steady-state economy…to return to more ‘appropriate’ technologies, to abandon ‘megaprojects,’ or to critique…a ‘metabolic rift’ with the rest of nature which,” they say, “[does] not exist.” Words like “commons” and “mutual aid” are classified as mere “buzzwords.” All arguments for “limits to growth” are by definition forms of “Malthusianism.” Nuclear power is to be promoted as a key solution to climate change and pollution generally. To cap it off, they contend, in social Darwinist terms, that capitalism itself is somehow integral to natural selection: “So as far as the rest of nature is concerned, whatever we humans do, via the capitalist mode of production or otherwise, from combustion of fossil fuels to the invention of plastics, is just the latest set of novel evolutionary selection pressures.”

Phillips has gone even further elsewhere: “The Socialist,” he declares, “must defend economic growth, productivism, Prometheanism.… Energy is freedom. Growth is freedom.” The ultimate goal is “more stuff.” What is required is “a high energy planet, not modesty, humility, and simple living.” With a brazen display of irrealism, Phillips bluntly asserts: “you can have infinite growth on a finite planet.” The earth, we are duly informed, can support “282 billion people”—or even more. Marxists who have questioned the nature of contemporary technology, such as Herbert Marcuse, are summarily dismissed as proponents of “neo-luddite positions.” Phillips openly celebrates Simon’s reactionary work, The Ultimate Resource, the bible of anti-ecological total exemptionalism (Leigh Phillips, Austerity Ecology and the Collapse-Porn Addicts: A Defence of Growth, Progress, Industry and Stuff [Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2015], 59, 63, 89, 250, 259).

Huber and Phillips’s bold advocacy of a “Promethean Marxism” in their Jacobin article was delivered with a panache that must have left the capitalist Breakthrough Institute green with envy. It has already led to a strong backlash in left-liberal environmental circles against the inanities of so-called “orthodox Marxism.” This can be seen in an article by Thomas Smith titled “Technology, Ecology and the Commons—Huber and Phillips’ Barren Marxism” (Resilience, March 21, 2024, resilience.org). Here we are told, in a further retreat from reason, that Huber and Phillips, in their total contempt for ecology, are simply “toeing the Marxist line,” promoting the “promethean Marxist dogma”—as if their views could be seen as representative of “orthodox Marxism” (which, as Georg Lukács famously said, is related entirely to method), or as if their outlook were one with that of Marxism in the world today. Neither is the case. In twenty-first-century conditions, socialism is ecology and ecology is socialism. Perhaps the most important aspect of Saito’s own analysis, despite all of the contradictions in his most recent work, is that it recognizes that a deep ecological view was present classically within the work of Marx (and, we would add, Engels), and that this constitutes a theoretical foundation on which all those committed to the philosophy of praxis today can draw in their struggles to create an economically egalitarian and ecologically sustainable world.

Ecosocialism and degrowth

First published at Monthly Review.

This interview by Arman Spéth with Monthly Review editor John Bellamy Foster is a revised and extended version of the interview first published in Spring 2024 in the journal Widerspruch, Beiträge zu sozialistischer Politik (Contradiction: Contributions to Socialist Politics), Zurich, Switzerland.

Degrowth is on the rise. In recent years, several internationally recognized publications have appeared that speak out in favor of the ecosocialist degrowth approach. The journal Monthly Review, of which you are editor, has adopted this approach recently in your special July–August 2023 issue, “Planned Degrowth: Ecosocialism and Sustainable Human Development.” What are the motives behind this and how do you explain the popularity of left-wing degrowth approaches?

Although “degrowth” as a term has caught on only recently, the idea is not new. Since at least May 1974, Monthly Review, beginning with Harry Magdoff and Paul M. Sweezy, has explicitly insisted on the reality of the limits of growth, the need to rein in exponential accumulation, and the necessity of establishing a steady-state economy overall (which does not obviate the need for growth in the poorer economies). As Magdoff and Sweezy stated at that time, “instead of a universal panacea, it turns out that growth is itself a cause of disease.” To “stop growth,” they argued, what was necessary was the “restructuring [of] existing production” through “social planning.” This was associated with a systematic critique of the economic and ecological waste under monopoly capitalism and the squandering of the social surplus.

Magdoff and Sweezy’s analysis gave a strong impetus to Marxian ecology in the United States, particularly in the fields of environmental sociology and ecological economics, for example in Charles H. Anderson’s The Sociology of Survival: Social Problems of Growth (1976) and Allan Schnaiberg’s The Environment: From Surplus to Scarcity (1980). So, “degrowth” in that sense is not new to us and is part of a long tradition, stretching over a half-century. Our “Planned Degrowth” issue merely sought to develop this argument further under the deepening contradictions of our time.

Yet, while Monthly Review has long insisted on the need to move in the rich countries to an economy of zero net capital formation, today this issue has become more urgent. The term “degrowth” has woken people up to what ecological Marxism has been saying for a very long time. It has become necessary, therefore, to provide a more precise answer as to what this means. The only answer possible is the one that the MR editors provided a half-century ago. Namely, there are two sides to the question. One is the negative one of stopping unsustainable growth (measured in terms of GDP). The other is the more positive one of promoting a planned social response to the capitalist accumulation regime. Our “Planned Degrowth” issue seeks to emphasize this more positive response, one which only ecosocialism can offer.

For ecosocialism, the notion of degrowth, although recognized as a necessity in the more developed economies in our time, in which ecological footprints per capita are greater than what the planet as a place of human habitation can support, has always been seen as simply part of an ecosocialist transition, and not in itself the essence of that transition. A degrowth path, insofar as it is one of deaccumulation, is directly opposed to the internal logic of capitalism, or the system of capital accumulation. In fact, I wrote an article in January 2011 called “Capitalism and Degrowth: An Impossibility Theorem.” The nature of the struggle means going against the logic of capitalist accumulation even while we exist within it. That is the historical character of revolution, today driven forward by absolute necessity. The struggle for human freedom and the struggle for human existence are now one.

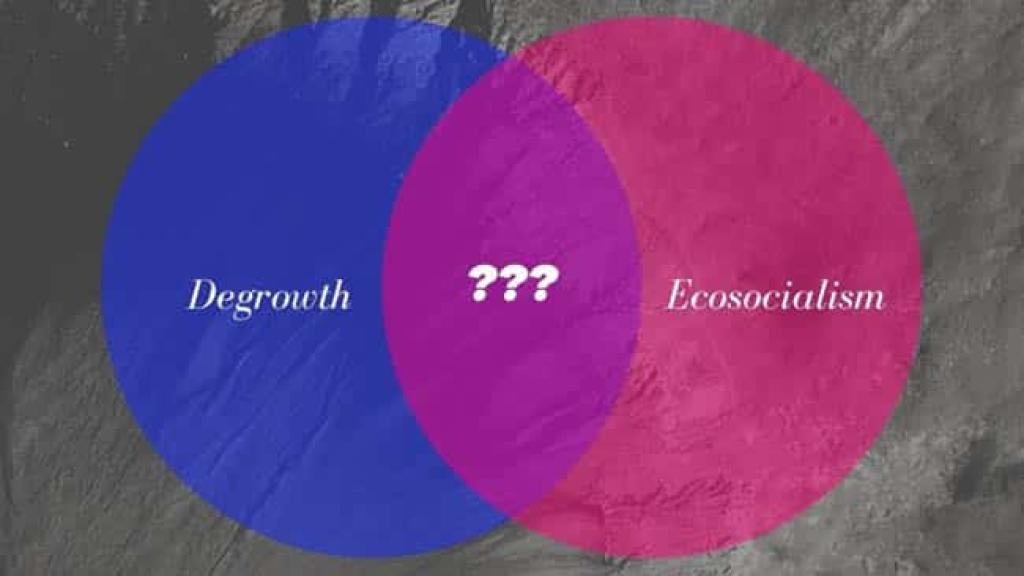

The relation of degrowth to ecosocialism is most straightforwardly expressed by Jason Hickel in an article titled “The Double Objective of Democratic Ecosocialism“ in the September 2023 issue of Monthly Review: “Degrowth…is best understood as an element within a broader struggle for ecosocialism and anti-imperialism.” It is a necessity in terms of present conditions in the rich, imperialist core of the capitalist economy, but not a panacea and not a sufficient basis in and of itself in defining ecosocialist change.

The July–August 2023 issue of Monthly Review was on “Planned Degrowth,” but the emphasis of the issue was on bringing planning to bear on our ecological problems more broadly. Thus, within ecosocialism, degrowth is merely a realistic recognition of contemporary imperatives centered in the rich economies with their enormous ecological footprints, while the proper emphasis is on ecosocialist planning rather than the degrowth category itself.

Part of the popularity of the term “degrowth” is because it so squarely offers an anticapitalist approach and cannot be co-opted by the system like so much else. But the overall approach of ecosocialism cannot be articulated just in negative terms, as the mere inverse of capitalist growth. Rather, it needs to be seen in terms of the transformation of human social relations and means of production by the associated producers.

In his bestselling book Slow Down (2024), Kohei Saito claims to have discovered an “epistemological break”—a major transformation in Karl Marx’s thinking in the last years of his life. Marx, he claims, had turned into a “degrowth communist” and discarded his “progressive view of history,” that is, abandoned the idea of the development of productive forces as the driving force of human development history. What do you think about this? How does your degrowth approach relate to your understanding of historical materialism?

Saito’s earlier book, Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism, was a valuable work. However, his more recent work, which includes Slow Down and Marx in the Anthropocene (2022), is wrong where the main theses that he advances with respect to Marx are concerned—even if the idea of degrowth communism, viewed in more general terms, is an important one.

It is true that Saito has raised some fundamental issues. Yet, there is very little that is new in his argument. Marxian ecology has stressed Marx’s theory of metabolic rift for a quarter-century. The fact that Marx advocated what has been called “sustainable human development” has been advanced over that entire period by Paul Burkett, me, and numerous others. Moreover, it has long been emphasized that the mature basis of this in Marx’s work was to be found in the Critique of the Gotha Programme and the letter (and draft letters) to Vera Zasulich—the very sources that Saito relies on almost exclusively in contending that Marx embraced degrowth communism. Even the focus of Marxist ecology on the contributions of Georg Lukács and István Mészáros, in this respect, is at least a decade old.

What can be considered new in Saito’s latest work is not substance but form, along with the exaggerated character of the argument that he now advances, which requires that he repudiate much of his own earlier analysis in Karl Marx’s Ecosocialism. In his new works, Saito introduces the notion that Marx altogether abandoned productivism/Prometheanism, which is supposed to have dominated Marx’s thinking at least in latent form as late as 1867 and the publication of Capital. Saito characterizes Marx’s Capital as a transitional work that incorporated an ecosocialist critique while not yet entirely surmounting historical materialism, which Saito himself identifies with productivism, technological determinism, and Eurocentrism. Only in 1868, we are told, did Marx engage in an epistemological break, rejecting the expansion of productive forces altogether, along with historical materialism, thus becoming a “degrowth communist.”

There are two fundamental problems with this. First, Saito is not able to provide a single shred of evidence that Marx in his final years was a degrowth communist in this sense of rejecting the expansion of productive forces. Nor, for that matter, is Saito able to provide evidence that Marx was Promethean and Eurocentric in his mature work in the 1860s (or even prior to that), insofar as Prometheanism is understood as production for production’s sake and Eurocentrism as the notion that European culture is the only universal culture. There is absolutely nothing to substantiate such allegations. The well-known fact that Marx saw collectivist/egalitarian possibilities in the Russian peasant commune (mir) is consistent with his overall outlook of sustainable human development. However, there is no justification for taking this to mean that he thought that a revolution in Tsarist Russia, still a very poor, underdeveloped, largely peasant country, could occur without the expansion of productive forces.

Second, the picture of Marx as a degrowth communist is a historical anachronism. Marx wrote at a time when industrial capitalism existed in only a small corner of the world, and, even then, transportation in London, at the center of the system, was still in the horse and buggy stage (not discounting the early railroad). There was no way that he could have envisioned the full-world economy of today, or the meaning that “degrowth” has assumed in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Saito’s analysis in his most recent works is therefore useful mainly in the controversy it has generated, and in the renewed focus on these issues that his work has provided. In the process, he indirectly has helped move us forward. Nevertheless, it is important to apply Marx’s method when analyzing the changed historical conditions of the present, and Saito’s jettisoning of historical materialism does not help in this respect.

You use the terms “degrowth” and “deaccumulation” interchangeably. Can you please explain what links these terms in your understanding?

“Degrowth” is an elusive term, like “growth” itself. The latter reflects the (often irrational) way that GDP is calculated under capitalism, expanding normal capitalist bookkeeping, based on a system of exploitation, to a national and even global level. The real issue is zero net capital formation, that is, instituting a process of deaccumulation. This has long been understood by Marxist ecological economists, as well as other, non-Marxist ecological economists, like the late Herman Daly. Growth, as Marx’s reproduction schemes demonstrate, is based on net capital formation. To recognize this is to emphasize that it is the system of capital accumulation that is the problem.

The idea of “planned degrowth” is at the center of your considerations. Could you explain what exactly you mean by this and how “planned degrowth” differs from other degrowth approaches?

I do not think there is anything complicated about this. Degrowth, and sustainable human development more generally, cannot occur without planning, which allows us to focus on genuine human needs and opens up all sorts of new possibilities blocked by the capitalist system. Capitalism works ex post, through the mediation of the market; planning is ex ante, allowing a straightforward approach to the satisfaction of needs, in line with what Marx in his “Notes on Adolph Wagner” called the “hierarchy of…needs.” Integrated democratic planning operating at all levels of society is the only route to a society of substantive equality and ecological sustainability and to human survival. Markets will still exist, but the path forward ultimately requires social planning in areas of production and investment controlled by the associated producers. This is especially the case in a planetary emergency such as today. As I have indicated, Magdoff and Sweezy argued as far back as May 1974 that stopping growth was essential in the rich economies, given the planetary ecological crisis, but that this needed to be approached more positively in terms of a planned restructuring of production as a whole.

Critics of degrowth

Cédric Durand in his September 2023 article in Jacobin, titled “Living Together,” criticizes the degrowth approach and writes “the abandonment of ‘the productive forces of capital’ and the scaling down of production would result in a de-specialisation of productive activity, leading to a dramatic reduction in the productivity of labour and, ultimately, a plunge in living standards.” Other critics, such as the economist Branko Milanovic, believe, as he wrote in “Degrowth: Solving the Impasse by Magical Thinking,” published on his SubStack in 2021, that degrowth advocates “engage in semi-magical and magical thinking,” because they cannot admit that the approach that they advocate would mean a loss of living standards for the vast majority of the population. How do you respond to these criticisms?

Durand and Milanovic would have a point if the question were one of “capitalist degrowth,” which, as I have already said, is an impossibility theorem. But the very changes needed to address today’s environmental and social crises have to do with changes in the parameters that define capitalism. Thus, attempts to criticize degrowth by insisting that it will reduce “productivity” increases, measured in narrow capitalist value-added terms, is simply to beg the question. The real issues have always been: productivity increases to what end, for whom, at what cost, requiring what level of exploitation, and measured by what criteria? What is the significance of increasing productivity in fossil fuel extraction if it points to the end of life on Earth as we know it? How many lives, as William Morris asked in the nineteenth century, have been rendered useless since compelled to produce useless and destructive goods at ever higher levels of “efficiency”?

Moreover, it is simply not true that economic growth is needed for productivity improvements, if this is seen in terms of real productivity increases (increase in output per labor hour), as opposed to increases in “productivity” measured simply as growth in value-added to GDP, which is a very narrow and misleading—even circular—conception. It is perfectly possible to generate endless qualitative improvements in production, reduce the labor time per unit of output, and thus, to advance efficiency, in a context of zero net capital formation, particularly in a socialist-oriented society. The productivity improvements in that case would be used to satisfy broad social needs, rather than for economic expansion for the enrichment of a few. They would be oriented primarily toward use value. Working hours could be reduced. It would mean that the benefits of productivity would be shared and human capacities in general would be augmented.

In his book Climate Change as Class War: Building Socialism on a Warming Planet (2022) and in his articles for Jacobin magazine, Matt Huber explicitly argues against your view, claiming that solving the ecological crisis requires massive technological expansion. How would you respond to this view?

Jacobin is now the principal left-social democratic journal in the United States, and Huber’s argument is developed in that vein. Social democracy, as opposed to socialism, has always been about a “third way” in which the irreconcilables of labor and capital (today, also including the irreconcilables of capitalism and the earth) can supposedly be reconciled via such means as new technology, increased productivity, regulated markets, formal labor organization, and the capitalist welfare (or environmental) state. However, the basic system would remain untouched. The idea is that social democracy can organize capitalism better than liberalism, not that it will go against capitalism’s fundamental logic. Huber in his book throws into the mix capitalist ecological modernization in a form that does not differ much from liberal ecological modernization, as represented by the Breakthrough Institute, but with the addition, in his case, of organized electrical workers. This perspective has consistently defined Jacobin’s approach to environmental issues, which has generally been opposed to ecosocialism and environmentalism more broadly. I wrote an article titled “The Long Ecological Revolution“ in Monthly Review in November 2017, questioning Jacobin’s strongly ecomodernist approach in this respect, which has included pieces by the author Leigh Phillips, who, in his book Austerity Ecology and the Collapse-Porn Addicts (2015), went so far as to suggest that “the planet can sustain up to 282 billion people…by using all the land[!]” and other similar absurdities.

In an article that Huber cowrote with Phillips in Jacobin in March of this year (“Kohei Saito’s ‘Start from Scratch’ Degrowth Communism”), the two authors reject the planetary boundaries framework advanced by today’s scientific consensus, which seeks to demarcate the biophysical limits to the earth as a safe home for humanity. In the planetary boundaries/Earth System framework, climate change is depicted as just one of nine such boundaries, the transgression of any one of which threatens human existence. In contrast, Huber and Phillips adopt a position virtually identical to that of the neoclassical economist Julian Simon, author of The Ultimate Resource (1981), who pioneered in propagating the notion of total human exemptionalism, according to which there are no real environmental limits to the quantitative expansion of the human economy that could not be overcome by technology; that it is possible to have infinite growth on a finite planet. On this basis, Simon was recognized as the foremost anti-environmentalist apologist for capitalism of his day. In this view, technology solves all problems irrespective of social relations. In near identical fashion, “the only true, permanently insuperable limits that we face,” Huber and Phillips reductionistically claim, “are the laws of physics and logic”—as if the biophysical limits of life on the planet were not an issue. Climate change, according to this view, is merely a temporary problem to be solved technologically, not a social-relational (or even ecological-relational) one. But for Marxists, social relations and technology, while distinguishable, are inextricably and dialectically entangled. An outlook that denies the planetary crisis by resorting to the promise of a technological deus ex machina, while absenting both historical and ecological limits, is in conflict with historical materialism, ecosocialism, and contemporary science—all three.

Today’s scientific consensus, as represented, for example, by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—particularly the stances taken by scientists, rather than governments involved in the process—states with absolute clarity that technology alone will not save us, and that we need a revolutionary-scale challenge to the present political-economic hegemony. We are now on the verge of a 1.5°C increase in global average temperature, and a 2°C increase will not be far beyond that if we do not act quickly. We have now crossed six of the nine planetary boundaries, with the likelihood of crossing still more. Yet, this trajectory could be altered. We already have all the technologies we need to address the planetary crisis, provided that the necessary changes are made in existing social relations. But there is the rub.

Huber and Phillips polemically reject degrowth as a backward strategy, even if organized on a planned ecosocialist basis. They argue rather that net capital accumulation can continue indefinitely if it is greened and if there is a reconciliation between capital and labor, and capital and the earth, along ecomodernist lines. At best this can be seen as the Green New Deal approach, or ecological Keynesianism. But their overall thrust goes beyond that and is, in fact, one of total human exemptionalism in which all lasting environmental limits, associated with the biogeophysical cycles of the earth, are denied. The main fault I find in this analysis is that it is willing to forego scientific realism and dialectical critique for political expediency, ending up with a kind of techno-utopian reformism that in fact goes nowhere, since it backs off from any serious confrontation with the capitalist system. This is hardly rational when the issue is a social system that is now threatening—in a matter of years and decades, not centuries—to transgress the conditions of the planet as a safe place of humanity. There is nothing socialist or ecological about such views.

What to do?

In your article “Planned Degrowth,” you emphasize the need for a revolutionary transformation to overcome ecological challenges. Could you explain what you mean by revolutionary transformation and why you believe it is essential? And how would you respond to the arguments that follow the principle of the “lesser evil” and support the possibility of an ecological transformation within the capitalist system, partly due to the urgency of the situation?

Today’s science says that we need changes in our socioeconomic system, applied technology, and our entire relation to the Earth System, if humanity is not to lay the basis this century for its own complete destruction. If the necessary, urgent transformations in the mode of production (which includes social relations) are not made, we will see death and dislocation of hundreds of millions, perhaps even billions, of people due to climate change this century. Climate change, moreover, is only part of the problem. We have now dumped 370,000 different synthetic chemicals into the environment, most of which are untested and many of which are toxic: carcinogenic, teratogenic, and mutagenic. Plastics, another novel entity in the planetary boundaries classification, are now out of control, with the proliferation globally and in the human body of microplastics, and even nanoplastics (small enough to cross cell walls). Billions of plastic sachets are being marketed by multinational corporations, primarily in the Global South. Global water shortages are growing, forests and ground cover generally are vanishing, and we are facing the sixth mass extinction in the history of the planet.

With six of the nine planetary boundaries now crossed, we are facing unprecedented dangers to human existence, and an existential crisis for humanity. The cause common to all these planetary crises is the system of capital accumulation, and all immediate solutions mean going against the logic of capital accumulation. The struggle will naturally occur within the present system, but in every moment of this struggle we are faced with the urgency of putting people and the planet before profit. There is no other way. Capitalism is dead to humanity.

The scale of the change required must be measured in terms of both time and space. Our relation to both today necessarily must be revolutionary and stretch around the globe. Whether we will succeed or not is something we cannot know at present. But we do know that this will be humanity’s greatest struggle. In this situation there is no “lesser evil.” As Marx said, on a much smaller scale in relation to Ireland in his day, it is “ruin or revolution.”

Finally, how do you assess the feasibility of ecosocialist degrowth with regard to the current political realities (Kräfteverhältnisse)? Where do you see opportunities, where do you see obstacles?

Opportunities are everywhere. Obstacles, largely a product of the present system, are also everywhere. As Naomi Klein said of climate change: This Changes Everything. Nothing can or will remain the same. That is the very definition of a revolutionary situation.

The most concrete and comprehensive study of what could be done practically in our present circumstances is to be found in Fred Magdoff and Chris Williams’s 2017 book, Creating an Ecological Society: Toward a Revolutionary Transformation. As Noam Chomsky said of their book, it demonstrates “that the ‘revolutionary systematic change’ necessary to avert catastrophe is within our reach.”

John Bellamy Foster is editor of Monthly Review and professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Oregon. Arman Spéth is a PhD student at Bard College, Berlin, studying the development of capitalism in post-Soviet Kazakhstan. Until the end of April 2024, he was also an editor of Widerspruch.