Narrative X-ray: Does Russia want peace?

31.12.2023

Russia claims it wants peace and is not to blame for starting wars, but the facts show that the narrative systematically repeated by key Kremlin figures is false. In the same way, Russia’s calls for peace with Ukraine are hollow because fulfilling the conditions set as their basis would mean suicide for Ukraine. The Kremlin unequivocally wants to usurp Ukraine and other neighbours and has essentially declared a covert war on the entire West.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has issued a new demand for the complete withdrawal of Ukrainian troops from the territories of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson, suggesting this as a precondition for initiating peace negotiations. According to a report from the state news agency Tass, Putin made these remarks during a meeting with the leadership of the Russian Foreign Ministry.

Putin stated that if Ukraine begins a “real withdrawal of troops from these regions” and formally abandons its plans to join NATO, Russia will immediately issue an order to cease fire and commence negotiations. “As soon as this happens, we will ensure the unhindered and safe withdrawal of Ukrainian forces,” he said, emphasizing Moscow’s commitment to facilitating a peaceful resolution.

The Russian president also warned that if Kyiv rejects this peace proposal, Russia’s future demands will differ, though he did not specify what those might entail.

On December 29, 2023, US President Joe Biden stated the recent Russian airstrike on Ukrainian cities and civilian targets, the largest to date, saying, “This is a stark reminder to the world that after nearly two years of destructive war, Putin’s goals remain the same. He wants to wipe out Ukraine and subjugate the people of Ukraine. He must be stopped.”

Both now and in his speech to Congress in early December, Biden said that if Putin takes away Ukraine, he won’t stop there, he will go further, and the Baltic countries, Moldova and Poland, will be next. If Russia attacks NATO allies, the United States will intervene directly, Biden confirmed, and then the United States will have to fight a war on another continent. Therefore, it makes more sense for the US to support Ukraine and stop Putin now. This sums up the position of the Western countries: Russia has started a war, and the aggressor must be stopped in the bud.

Russia’s dove of peace narrative and threats

Russia’s talking points regarding the war in Ukraine have been the same all along: Russia did not start the war, but acted in self-defense; the war is not an aggression against Ukraine, but a “special military operation” against the threat to Russia, which is said to be the “Nazi regime” of Ukraine, which committed “genocide” against Russians in Eastern Ukraine and is driving the country towards NATO, which, in turn, means that the “hostile” bloc’s border with Russia is expanding. Therefore, it is necessary to “denazify” the country. These noble goals justify a war with a fraternal nation, which is not a war at all.

Russian President Vladimir Putin said after Biden’s speech in Congress that the US President’s suggestion that Russia wants to attack NATO countries after annexing Ukraine is “complete nonsense.” “Russia has no reason or interest—neither geopolitical, economic, nor military—to go to war with NATO countries,” Putin said in an interview with the Russian TV channel Rossija1 in the TV program “Moscow. The Kremlin. Putin”. “We have no territorial demands on them and do not wish to spoil relations with them.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin said after Biden’s speech in Congress that the US President’s suggestion that Russia wants to attack NATO countries after annexing Ukraine is “complete nonsense.” “Russia has no reason or interest—neither geopolitical, economic, nor military—to go to war with NATO countries,” Putin said in an interview with the Russian TV channel Rossija1 in the TV program “Moscow. The Kremlin. Putin”. “We have no territorial demands on them and do not wish to spoil relations with them.”

According to Putin, the Kremlin’s wishes are the opposite: Russia wants to develop good relations with NATO countries.

In the same interview, Putin made veiled threats towards Finland, which had just been accepted into NATO, including that the country “has problems”, and promised to concentrate military units on the Russian-Finnish border. The possibility of Finland attacking Russia defies common sense.

On July 21, 2023, after Poland sent military units to secure the Polish-Belarusian border in response to Wagner’s redeployment of troops to Belarus, Putin threatened Poland in a televised appearance, saying that Russia would respond with “all possible means at our disposal.” Poland is known to be a NATO country and has not expressed any desire to attack Ukraine or Belarus. “Poland wants to form some kind of coalition under the umbrella of NATO and intervene directly in the conflict in Ukraine, to get a fatter piece for itself, to get back its so-called historical territories,” Putin said.

On July 21, 2023, after Poland sent military units to secure the Polish-Belarusian border in response to Wagner’s redeployment of troops to Belarus, Putin threatened Poland in a televised appearance, saying that Russia would respond with “all possible means at our disposal.” Poland is known to be a NATO country and has not expressed any desire to attack Ukraine or Belarus. “Poland wants to form some kind of coalition under the umbrella of NATO and intervene directly in the conflict in Ukraine, to get a fatter piece for itself, to get back its so-called historical territories,” Putin said.

In a speech in October 2023, Putin said that Western leaders had “lost their sense of reality and crossed all boundaries. “We did not start the so-called war in Ukraine. On the contrary, we are trying to end it,” Putin spoke as a dove of peace at the meeting of the international Valdai discussion club.

Already in 2016, at a meeting of the same club, he said that Russia was not going to attack anyone: “It is simply unthinkable, stupid and completely unrealistic.”

On the contrary, according to Putin, the USA is trying to incite military action in Ukraine to maintain its global supremacy.

Russia’s dove-of-peace narrative is also cringing when you look at where the Russian Federation has intervened militarily during its short existence: 1991-1993 in Georgia and South Ossetia, 1992-93 in Abkhazia, 1992 in Transnistria and North Ossetia, 1992-97 in Tajikistan, 1994-96 and 1999-2009 in Chechnya, in 1999 in Dagestan, and 2008 in Georgia for the secession of South Ossetia. So far, Russia has been involved in one way or another: since 2015 in support of the al-Assad regime in Syria, since 2018 in the civil war in the Central African Republic, and since 2018 in the war in Mali. Not to mention that Russia started to take pieces from Ukraine already in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea and the shadow war in Donbas.

The real danger: Russia does not stick to the agreements

Many analysts see Putin’s peace dove talk as a narrative aimed at blurring reality and dividing the West because Putin has violated almost every relevant agreement and consistently lied as if he lived in a parallel universe.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, an international agreement was concluded in Budapest in 1994, based on which Ukraine surrendered its existing arsenal of nuclear weapons to Russia. In return, Russia recognized Ukraine’s territorial integrity and political independence under the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances. Russia has violated this agreement.

Already at the beginning of the war or before it, the Russian president rejected a preliminary agreement between Russian and Ukrainian negotiators, according to which Ukraine would have agreed not to join NATO, and Russian forces would have ended the military campaign against Ukraine. According to Mykhailo Podoljak, adviser to the President of Ukraine, Russia used pre-invasion negotiations as a smokescreen to prepare for an advance on Ukraine.

Putin’s current claims about not wanting to attack NATO countries are similar to the Kremlin’s messages in late 2021 and early 2022, even the night before hostilities began on February 24, 2022, when Putin and other senior Russian officials lied in unison: Russia is not going to attack Ukraine. At the same time, Russia concentrated more than 100,000 troops on the Ukrainian border.

Therefore, according to the ISW analysis of the US Independent Institute for the Study of War (17.12.2023), Putin’s claims that Russia has no desire to attack NATO countries are hollow.

In August 2023, the head of the Russian Security Council, Dmitry Medvedev, said that Russia has the right to act against NATO countries based on the principles of jus ad bellum (legitimate reasons for starting a war).

In November, Medvedev threatened Poland, saying the country could lose its independence. On December 2, he said on state television that the Baltic states could be Russia’s next targets.

Medvedev, Vladimir Solovyov, and other Russian propagandists have repeatedly threatened to use nuclear weapons against NATO countries. ISW experts say propagandists’ threats are not credible in themselves, but they are important in connection with Putin’s recent “peacemaking attempt,” the real goal of which is to weaken the unity of the West and force NATO to revise its principles in the direction that Russia wants.

According to ISW experts, Putin’s recent statements that it is not Russia, but the US that needs to find a common ground, are thinly veiled threats towards the US and NATO.

A peace agreement is unlikely at this stage

There have been constant attempts at peace or a truce, but none of them have succeeded.

At the November 2023 video meeting of the G20 countries under the presidency of India, Putin said that Russia has never refused peace talks with Ukraine, but it is Ukraine that has withdrawn from the talks. It was the first time Putin had to directly endure accusations of aggression from heads of state, and the first time he called the war a “war” (rather than a special operation) and a “tragedy.” “Of course, we should think about how to end this tragedy. By the way, Russia has never refused peace talks with Ukraine,” said Putin.

In July 2023, Putin confirmed at a meeting of representatives of African countries and Russia in St. Petersburg that the proposals of African leaders for peace talks could be the basis for ending the war, but that Kyiv’s attacks on Russia make it “almost impossible”.

Before, China presented a 12-point peace plan, in which the first point is to respect the sovereignty and borders of countries under the principles of the United Nations. It has not affected Putin’s aggression in Ukraine in the desired direction.

Together with Crimea, which was annexed by Russia in 2014, the Kremlin currently controls about 17.5% of Ukraine’s territory. As a condition of the peace talks, the Kremlin wants the ceasefire border to be fixed on the current front line and that part of Ukraine to remain under Russian control. According to analysts, such an outcome may suit Putin because it can be presented as a victory and “fulfilment of objectives,” which is Putin’s main condition for ending hostilities.

However, this does not suit Ukraine in any way, because Kiev’s prerequisite is the withdrawal of Russian troops from the pre-war borders. Therefore, Putin’s “dove of peace” narrative is empty.

The President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelelsnkyi, presented a 10-point peace plan for Ukraine already at the end of 2022, and its main conditions are the cessation of hostilities, the restoration of Ukrainian territory to the borders fixed in 1994, the withdrawal of Russian troops from there, and the prosecution of war criminals. “There is no alternative to this peace plan: only Ukraine, the country fighting this aggression, can determine what a just and lasting peace looks like. Therefore, all proposals for peaceful reconciliation can only be based on the Ukrainian peace formula,” reads the explanation of the Ukrainian peace formula.

The President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelelsnkyi, presented a 10-point peace plan for Ukraine already at the end of 2022, and its main conditions are the cessation of hostilities, the restoration of Ukrainian territory to the borders fixed in 1994, the withdrawal of Russian troops from there, and the prosecution of war criminals. “There is no alternative to this peace plan: only Ukraine, the country fighting this aggression, can determine what a just and lasting peace looks like. Therefore, all proposals for peaceful reconciliation can only be based on the Ukrainian peace formula,” reads the explanation of the Ukrainian peace formula.

Analysts reasonably believe that even if Putin is forced to start peace talks, nothing will happen until a new president is elected in the US, preferably Trump, with whom he would have better opportunities to achieve his goals.

At the same time, ideas in the Western media are emerging that the war could also be ended by Ukraine giving up parts of the territories occupied by Russia, or at least a ceasefire should be concluded. Unfortunately, it is obvious that under the conditions of a ceasefire, where the war border is frozen, Putin would simply take advantage to consolidate his positions and/or prepare a new offensive.

Also, dangerous rhetoric has started to sound in the Western media, as if Zelenskyy, and not Putin, should try to make peace – even though the latter is the aggressor. However, Zelenskyi has already formulated the principles for achieving peace.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said at the end of December that influential Western powers had just met under cover of secrecy to discuss the peace formula presented by Zelenskyy. According to Lavrov, the next meeting has been arranged for January 2024, as well as the start of peace talks in February. However, the Reuters news agency was unable to confirm these claims.

Putin has repeatedly stated that Russia is always ready for peace talks, but only on Russia’s terms.

If you read the interview of Maria Zakharova, spokeswoman for the Russian Foreign Ministry, published on December 6, 2023, for AFP, unfortunately, all hopes for peace are extinguished. Zakharova, speaking on behalf of Lavrov, who is in turn hosted by Putin, formulated the preconditions for peace talks as follows: the West must stop supplying Ukraine with weapons, Kyiv must accept the new territorial reality, Ukraine must become a neutral state, and the rights of Russians must be protected. “We cannot tolerate the existence of an aggressive Nazi state on our border, from whose territory the threat to Russia and its neighbors emanates,” Zakharova repeated the Kremlin’s long-known talking points, which make effective peace talks impossible. Or why should Ukraine voluntarily commit suicide, as some analysts rhetorically asks.

The number of pro-peace activists in Russia has increased

The fact that the Kremlin does not want peace does not mean that the people of Russia want the war to continue. According to the latest survey by the private Russian research company Russian Field, 39% of the respondents are in favor of continuing the “special military operation,” and 48% are in favor of moving to peace talks. This shows a significant shift: in a poll in early February, 45% were in favor of war and 44% were in favor of peace talks. A year earlier, there were even more supporters of the war. For the first time, there are now more opponents of war than supporters of its continuation. Moreover, when asked directly whether they would support Putin’s decision to sign the peace treaty, 74% said yes and only 18% said no. In addition, 61% of Russians have a negative view of a possible second wave of mobilization.

This direction is also supported by the polls of the largest independent research company, Levada. According to the data from the last two polls, the share of doves for peace has increased in October, compared to September, from 51% to 56%, and the share of supporters of war has fallen from 39% to 37%.

However, one cannot overlook the fact that the majority of respondents to the Levada survey “strongly support” (45%) or “rather support” (31%) the activities of the Russian armed forces in Ukraine—a total of 76%. According to Russian Field, the corresponding numbers are 47% and 33%, for a total of 80%.

However, based on what is known, war is more useful to the Putin regime than peace, at least as long as it can serve as its achievement. It is also clear that the survival of Putin’s regime depends on how the war ends, but for now, it is more profitable for him to continue the war than to end it. Only when war becomes a threat to his power Putin will have a real desire to end it.

The ISW Institute for the Study of War has aptly summarized Russia’s aggression: “Putin did not attack Ukraine because he was afraid of NATO. He attacked because he thought NATO was weak and his attempts to regain control of Ukraine by other means had failed, and installing a Russia-friendly government in Kyiv was supposed to be safe and easy. His goal was not to protect Russia from some non-existent threat but to expand Russia’s power, destroy the state of Ukraine, and destroy NATO. Those are the goals he’s still trying to achieve.”

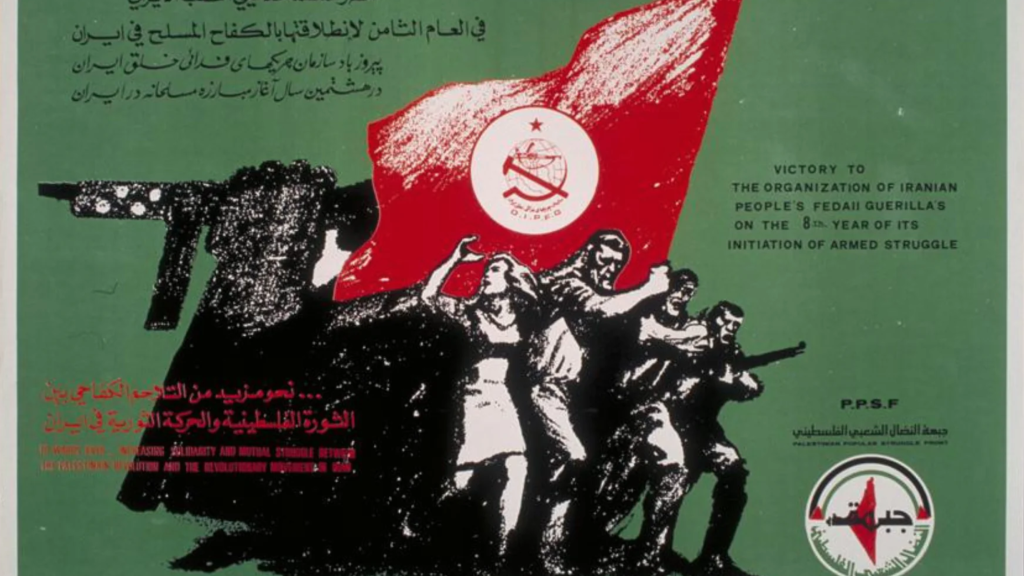

The infographic was created by Propastop’s editors.