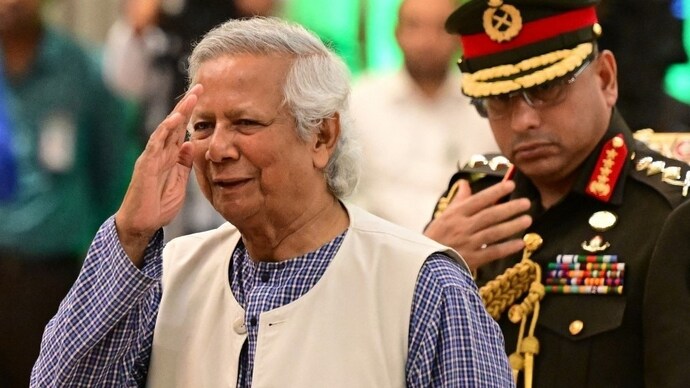

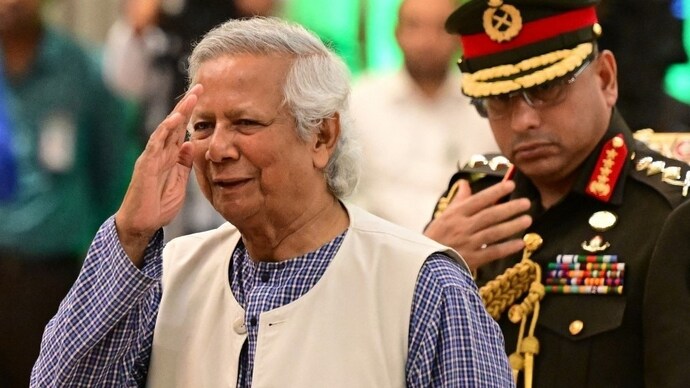

Bangladesh will maintain support for Rohingya refugees, says Muhammad Yunus

Muhammad Yunus has vowed to continue supporting the Rohingya refugees and the garment trade in Bangladesh. Yunus, who took office after a student-led protest.

Muhammad Yunus pledges continued support for Rohingya refugees and garment trade.

Agence France-Presse

Dhaka,UPDATED: Aug 19, 2024

In ShortYunus took office after a student-led revolution ousted Sheikh Hasina

Bangladesh's garment industry accounts for 85% of its $55 billion annual exports

Yunus returned from Europe this month

Bangladesh will maintain support both for its immense Rohingya refugee population and its vital garment trade, Nobel laureate and new leader Muhammad Yunus said Sunday in his first major policy address.

Yunus, 84, returned from Europe this month after a student-led revolution to take up the monumental task of steering democratic reforms in a country riven by institutional decay.

His predecessor Sheikh Hasina, 76, had suddenly fled the country days earlier by helicopter after 15 years of iron-fisted rule.

Setting out his priorities in front of diplomats and UN representatives, Yunus vowed continuity on two of the biggest policy challenges of his caretaker administration.

"Our government will continue to support the million-plus Rohingya people sheltered in Bangladesh," Yunus said.

"We need the sustained efforts of the international community for Rohingya humanitarian operations and their eventual repatriation to their homeland, Myanmar, with safety, dignity and full rights," he added.

Bangladesh is home to around one million Rohingya refugees.

Most of them fled neighbouring Myanmar in 2017 after a military crackdown now the subject of a genocide investigation by a United Nations court.

The weeks of unrest and mass protests that toppled Hasina also saw widespread disruption to the country's linchpin textile industry, with suppliers shifting orders out of the country.

"We won't tolerate any attempt to disrupt the global clothing supply chain, in which we are a key player," Yunus said.

Bangladesh's 3,500 garment factories account for around 85 percent of its $55 billion in annual exports.

Yunus won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for his pioneering work in microfinance, credited with helping millions of Bangladeshis out of grinding poverty.

He took office as "chief adviser" to a caretaker administration -- all fellow civilians bar two retired generals -- and has said he wants to hold elections "within a few months".

Before her ouster, Hasina's government was accused of widespread human rights abuses, including the mass detention and extrajudicial killing of her political opponents.

She fled the country on August 5 to neighbouring India, her government's biggest political patron and benefactor, when protesters swarmed into the capital Dhaka to force her out of office.

'Hundreds were killed'

"Hundreds of thousands of our valiant students and people rose up against the brutal dictatorship of Sheikh Hasina," Yunus said during his address, at times visibly emotional.

"She fled the country, but only after the security forces and her party's student wing committed the worst civilian massacre since the country's independence," he added.

"Hundreds were killed, thousands were injured."

More than 450 people were killed between the start of a police crackdown on student protests and her ouster three weeks later.

'Dictatorship'

A UN fact-finding mission is expected in Bangladesh soon to probe "atrocities" committed during that time.

"We want an impartial and internationally credible investigation into the massacre," Yunus said on Sunday.

"We will provide whatever support the UN investigators need."

Yunus again committed to hold free and fair elections "as soon as we can complete our mandate to carry out vital reforms in our election commission, judiciary, civil administration, security forces, and media".

"The Sheikh Hasina dictatorship destroyed every institution of the country," he said.

He added that his administration would "make sincere efforts to promote national reconciliation".

Muhammad Yunus has vowed to continue supporting the Rohingya refugees and the garment trade in Bangladesh. Yunus, who took office after a student-led protest.

Muhammad Yunus pledges continued support for Rohingya refugees and garment trade.

Agence France-Presse

Dhaka,UPDATED: Aug 19, 2024

In ShortYunus took office after a student-led revolution ousted Sheikh Hasina

Bangladesh's garment industry accounts for 85% of its $55 billion annual exports

Yunus returned from Europe this month

Bangladesh will maintain support both for its immense Rohingya refugee population and its vital garment trade, Nobel laureate and new leader Muhammad Yunus said Sunday in his first major policy address.

Yunus, 84, returned from Europe this month after a student-led revolution to take up the monumental task of steering democratic reforms in a country riven by institutional decay.

His predecessor Sheikh Hasina, 76, had suddenly fled the country days earlier by helicopter after 15 years of iron-fisted rule.

Setting out his priorities in front of diplomats and UN representatives, Yunus vowed continuity on two of the biggest policy challenges of his caretaker administration.

"Our government will continue to support the million-plus Rohingya people sheltered in Bangladesh," Yunus said.

"We need the sustained efforts of the international community for Rohingya humanitarian operations and their eventual repatriation to their homeland, Myanmar, with safety, dignity and full rights," he added.

Bangladesh is home to around one million Rohingya refugees.

Most of them fled neighbouring Myanmar in 2017 after a military crackdown now the subject of a genocide investigation by a United Nations court.

The weeks of unrest and mass protests that toppled Hasina also saw widespread disruption to the country's linchpin textile industry, with suppliers shifting orders out of the country.

"We won't tolerate any attempt to disrupt the global clothing supply chain, in which we are a key player," Yunus said.

Bangladesh's 3,500 garment factories account for around 85 percent of its $55 billion in annual exports.

Yunus won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for his pioneering work in microfinance, credited with helping millions of Bangladeshis out of grinding poverty.

He took office as "chief adviser" to a caretaker administration -- all fellow civilians bar two retired generals -- and has said he wants to hold elections "within a few months".

Before her ouster, Hasina's government was accused of widespread human rights abuses, including the mass detention and extrajudicial killing of her political opponents.

She fled the country on August 5 to neighbouring India, her government's biggest political patron and benefactor, when protesters swarmed into the capital Dhaka to force her out of office.

'Hundreds were killed'

"Hundreds of thousands of our valiant students and people rose up against the brutal dictatorship of Sheikh Hasina," Yunus said during his address, at times visibly emotional.

"She fled the country, but only after the security forces and her party's student wing committed the worst civilian massacre since the country's independence," he added.

"Hundreds were killed, thousands were injured."

More than 450 people were killed between the start of a police crackdown on student protests and her ouster three weeks later.

'Dictatorship'

A UN fact-finding mission is expected in Bangladesh soon to probe "atrocities" committed during that time.

"We want an impartial and internationally credible investigation into the massacre," Yunus said on Sunday.

"We will provide whatever support the UN investigators need."

Yunus again committed to hold free and fair elections "as soon as we can complete our mandate to carry out vital reforms in our election commission, judiciary, civil administration, security forces, and media".

"The Sheikh Hasina dictatorship destroyed every institution of the country," he said.

He added that his administration would "make sincere efforts to promote national reconciliation".

In their efforts to stay in power, Sheikh Hasina's dictatorship destroyed every institution of the country. The judiciary was broken. Democratic rights were suppressed, says Yunus

PTI

Dhaka

Published 18.08.24

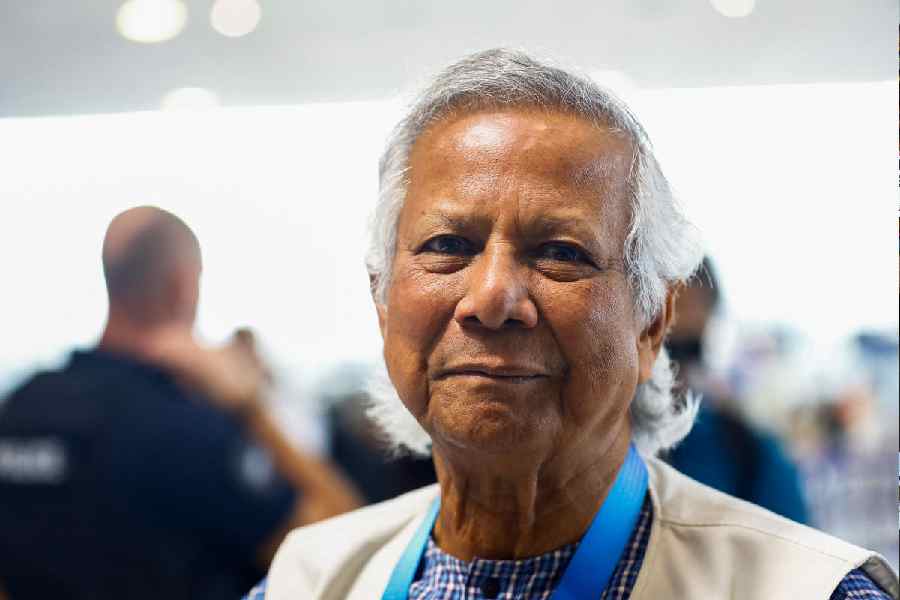

Muhammad Yunus.

Bangladesh's interim government chief Muhammad Yunus on Sunday accused deposed prime minister Sheikh Hasina of destroying every institution of the country in her efforts to stay in power as he promised to hold a free, fair and participatory election as soon as his government completes the "mandate" of carrying out "vital reforms." Hasina, 76, resigned and fled to India on August 5 following a massive protest by students against a controversial quota system in government jobs.

After Hasina's ouster, 84-year-old Yunus took oath as the Chief Adviser of the interim government on August 8.

“In their efforts to stay in power, Sheikh Hasina's dictatorship destroyed every institution of the country. The judiciary was broken. Democratic rights were suppressed through a brutal decade-and-a-half long crackdown," United News of Bangladesh quoted Yunus as saying through his Press Secretary Shafiqul Alam.

His comments came as he briefed diplomats stationed in Dhaka for the first time since the interim government's inception.

Yunus said he took over a country which was in many ways a complete mess.

He emphasises on required reforms in the Election Commission, judiciary, civil administration, security forces and media.

The chief adviser said elections were rigged blatantly and generations of young people grew up without exercising their voting rights.

“Banks were robbed with full political patronisation. And the state coffer was plundered by abusing power,” Yunus said, adding that they will also make sincere efforts to promote national reconciliation.

Yunus said they will undertake robust and far-reaching economic reforms to restore macroeconomic stability and sustained growth, with priority attached to good governance and combating corruption and mismanagement.

He said the top priority of the interim government would be to bring the law and order situation under control.

“We will be close to normalcy within a short period, with the unwavering support of our people and patriotic armed forces,” Yunus said.

The police force has also resumed its operations. The armed forces will continue to serve in aid of civil power as long as the situation warrants.

“Our government remains pledge-bound to ensure the safety and security of all religious and ethnic groups,” he said.

Bangladesh saw a spike in violence against members of Hindu communities following the fall of the Hasina-led government.

Yunus said the interim government will hold a "free, fair participatory" election as soon as it completes the "mandate" to carry out "vital reforms." He said they have also made it a priority to ensure justice and accountability for all the killings and violence committed during the recent mass uprising.

He said they will uphold and promote all their international legal obligations, including international humanitarian law and international human rights law.

"Our government will adhere to all international, regional and bilateral instruments it is a party to. Bangladesh shall continue to remain an active proponent of multilateralism, with the UN at the core," Yunus said.

"Our government will nurture friendly relations with all countries in the spirit of mutual respect and understanding and shared interests," he said.

He called upon their trade and investment partners to maintain their trust in Bangladesh for economic prosperity.

“Bangladesh stands at the crossroads of a new beginning. Our valiant students and people deserve a lasting transformation of our nation. It is a difficult journey and we need your help along the way. We need to fulfil their aspirations. The sooner the better,” he said, adding that they have to create opportunities to build a poverty-free and prosperous new Bangladesh.

“We believe all our friends and partners in the international community will stand by our government and people as we chart a new democratic future,” said Yunus.

Yunus paid deep respect and homage to all those valiant students and innocent people who made the supreme sacrifice.

“Students of no other countries in our recent memory had to pay so much a price for expressing their democratic aspirations, dreaming a discrimination-free, equitable and environmentally-friendly nation where human rights of every citizen are fully protected,” he said.

He sought the international community’s support to rebuild Bangladesh.

On the Rohingya issue, he said the interim government will continue to support the million-plus Rohingya people sheltered in Bangladesh.

"We need sustained efforts of the international community for Rohingya humanitarian operations and their eventual repatriation to their homeland, Myanmar, with safety, dignity and full rights," Yunus said.

He said the interim government looks forward to maintaining and enhancing Bangladesh’s contributions to the UN peacekeeping operations

Muhammad Yunus.

Bangladesh's interim government chief Muhammad Yunus on Sunday accused deposed prime minister Sheikh Hasina of destroying every institution of the country in her efforts to stay in power as he promised to hold a free, fair and participatory election as soon as his government completes the "mandate" of carrying out "vital reforms." Hasina, 76, resigned and fled to India on August 5 following a massive protest by students against a controversial quota system in government jobs.

After Hasina's ouster, 84-year-old Yunus took oath as the Chief Adviser of the interim government on August 8.

“In their efforts to stay in power, Sheikh Hasina's dictatorship destroyed every institution of the country. The judiciary was broken. Democratic rights were suppressed through a brutal decade-and-a-half long crackdown," United News of Bangladesh quoted Yunus as saying through his Press Secretary Shafiqul Alam.

His comments came as he briefed diplomats stationed in Dhaka for the first time since the interim government's inception.

Yunus said he took over a country which was in many ways a complete mess.

He emphasises on required reforms in the Election Commission, judiciary, civil administration, security forces and media.

The chief adviser said elections were rigged blatantly and generations of young people grew up without exercising their voting rights.

“Banks were robbed with full political patronisation. And the state coffer was plundered by abusing power,” Yunus said, adding that they will also make sincere efforts to promote national reconciliation.

Yunus said they will undertake robust and far-reaching economic reforms to restore macroeconomic stability and sustained growth, with priority attached to good governance and combating corruption and mismanagement.

He said the top priority of the interim government would be to bring the law and order situation under control.

“We will be close to normalcy within a short period, with the unwavering support of our people and patriotic armed forces,” Yunus said.

The police force has also resumed its operations. The armed forces will continue to serve in aid of civil power as long as the situation warrants.

“Our government remains pledge-bound to ensure the safety and security of all religious and ethnic groups,” he said.

Bangladesh saw a spike in violence against members of Hindu communities following the fall of the Hasina-led government.

Yunus said the interim government will hold a "free, fair participatory" election as soon as it completes the "mandate" to carry out "vital reforms." He said they have also made it a priority to ensure justice and accountability for all the killings and violence committed during the recent mass uprising.

He said they will uphold and promote all their international legal obligations, including international humanitarian law and international human rights law.

"Our government will adhere to all international, regional and bilateral instruments it is a party to. Bangladesh shall continue to remain an active proponent of multilateralism, with the UN at the core," Yunus said.

"Our government will nurture friendly relations with all countries in the spirit of mutual respect and understanding and shared interests," he said.

He called upon their trade and investment partners to maintain their trust in Bangladesh for economic prosperity.

“Bangladesh stands at the crossroads of a new beginning. Our valiant students and people deserve a lasting transformation of our nation. It is a difficult journey and we need your help along the way. We need to fulfil their aspirations. The sooner the better,” he said, adding that they have to create opportunities to build a poverty-free and prosperous new Bangladesh.

“We believe all our friends and partners in the international community will stand by our government and people as we chart a new democratic future,” said Yunus.

Yunus paid deep respect and homage to all those valiant students and innocent people who made the supreme sacrifice.

“Students of no other countries in our recent memory had to pay so much a price for expressing their democratic aspirations, dreaming a discrimination-free, equitable and environmentally-friendly nation where human rights of every citizen are fully protected,” he said.

He sought the international community’s support to rebuild Bangladesh.

On the Rohingya issue, he said the interim government will continue to support the million-plus Rohingya people sheltered in Bangladesh.

"We need sustained efforts of the international community for Rohingya humanitarian operations and their eventual repatriation to their homeland, Myanmar, with safety, dignity and full rights," Yunus said.

He said the interim government looks forward to maintaining and enhancing Bangladesh’s contributions to the UN peacekeeping operations

Despite improvement in situation, minorities in Bangladesh remain worried

By Ariful Islam Mithu

Aug 18, 2024

HINDUSTAN TIMES

Leaders of minority communities met interim government head Muhammad Yunus on August 13 and raised concerns about attacks on their homes, businesses, and temples

Dhaka: Attacks on homes, businesses, and places of worship of religious minorities across Bangladesh have come down significantly over the past week, though these communities remain worried because of sporadic incidents of violence in different parts of the country

.

Bangladeshi Hindus protesting against the violence that has taken place against their businesses and homes after Sheikh Hasina’s ouster (AFP Photo)

Minorities in Bangladesh, mainly Hindus, who make up eight per cent of the population of nearly 170 million, faced attacks after former premier Sheikh Hasina stepped down and fled to India on August 5 following a month-long uprising against her regime in which at least 650 people died.

Minorities in Bangladesh, mainly Hindus, who make up eight per cent of the population of nearly 170 million, faced attacks after former premier Sheikh Hasina stepped down and fled to India on August 5 following a month-long uprising against her regime in which at least 650 people died.

Amid a power vacuum, the homes, places of worship, and businesses of religious minorities were attacked in parts of Bangladesh on August 5. Hindu temples were attacked and vandalised in Dhamrai in Dhaka, Natore, Kalapara in Patuakhali, Shariatpur, and Faridpur, while homes were attacked in Jessore, Noakhali, Meherpur, Chandpur, and Khulna. Some 40 shops owned by Hindus were vandalised in Dinajpur.

The interim government led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus assumed office on August 8, three days after the law and order situation completely broke down and there were no police personnel to protect the people.

Ashish Kumar Sarkar, an assistant professor at Ataikula Madpur Amena Khatun Degree College in Pabna district, said, “During that time when there was no government, we were in a situation where we didn’t know whom to call if anything happened.

“But now different political parties have given us assurances. As a result, we are now somewhat reassured,” he said. “The police are on duty, and army soldiers are patrolling the streets. We have someone to call on.”

However, Sarkar said Hindus are still facing attacks at some places. He believes some Hindus were attacked because of their affiliation with Hasina’s Awami League party, while some attacks on homes and businesses were carried out for the purpose of looting.

“The law and order situation has improved to some extent, but we haven’t completely overcome our fears,” said Sarkar.

Leaders of minority communities met Yunus on August 13 and raised concerns about attacks on their homes, businesses, and temples. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has called on Yunus to ensure the safety and security of minorities and also expressed concern about the security of Hindus during his Independence Day speech.

On Friday, Yunus dialed Modi and assured him of the security of all minorities in Bangladesh.

A Hindu businessman in Dhaka, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told HT that he felt more secure now than a week ago. Hindus are regaining confidence slowly, though they continue to have concerns because of isolated acts of violence. “But I can say there is a significant improvement even though our worries have not gone away,” the businessman said.

Every year, Hindus organise processions to celebrate Janmashtami, the festival marking the birth of Lord Krishna. This year, the festival falls on August 26. “If people feel safe, people will join in the celebratory processions. The police will have to create an environment so that people feel safe,” said the businessman.

Minority community leaders too said they continue to be worried despite a fall in reports of attacks on Hindus.

“We aren’t in a good condition, and our worries haven’t ended yet,” said Rana Dasgupta, general secretary of the Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Oikya Parishad. He alleged minority members are being forced to resign from government offices and colleges and as members of local government bodies.

“The forced resignations began on Saturday and are still going on in schools, universities, and city corporations in some places,” said Dasgupta. He said between 12pm and 3.20pm on Saturday, he received five phone calls about such forced resignations. However, he declined to give details.

Members of the Christian and Buddhist minorities said they were not very worried, though several homes of Santhals were attacked in Dinajpur and Rajshahi districts and a church was vandalised in Narayanganj.

Joyanta Rozario, a drama director, said the homes of Christians in Dinajpur’s Biral area, Rajshahi’s Tanore area, and a church at Narayanganj were vandalised. “Though Bangladesh is going through political instability, I don’t think I have to be worried about it for the time being,” said Rozario.

Noted musician Bartha Barua, a Buddhist who expressed solidarity with the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement and organised a concert at Dhanmondi in Dhaka during the protests, said some isolated incidents were occurring, but these were the handiwork of “opportunists. ” Communal harmony in Bangladesh is “good enough,” he said, adding, “I don’t consider myself a minority, never.”