‘Unlawful and aggressive’: Philippines say coast guard ships damaged after rammed by Chinese vessels in disputed waters

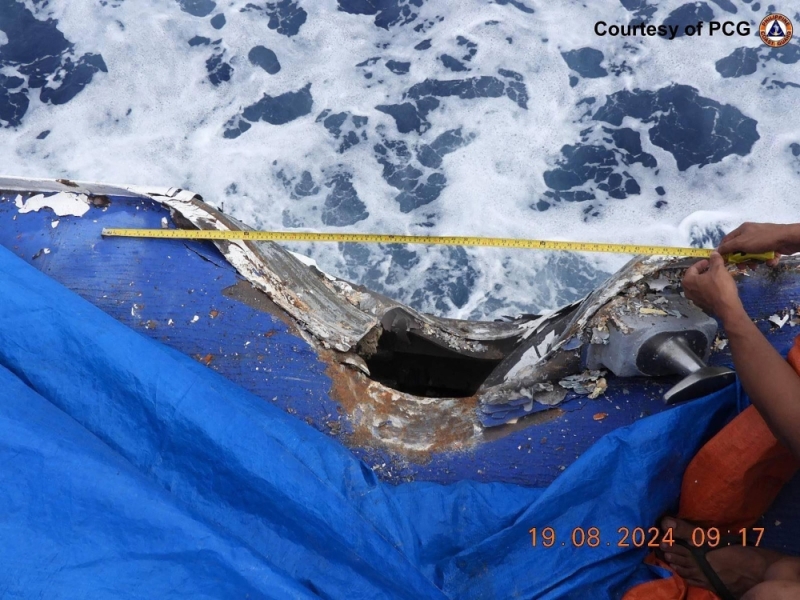

This handout photo taken and released by the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) on August 19, 2024 shows damage to the Coast Guard ship BRP Cape Engano (MRRV-4411) following a collision with a Chinese coast guard vessel near Sabina Shoal in disputed waters of the South China Sea.

Monday, 19 Aug 2024

BEIJING, Aug 19 — Chinese and Philippine vessels collided on Monday during a confrontation near a disputed shoal in the South China Sea, the two countries said.

China and the Philippines have had repeated confrontations in the vital waterway in recent months, including around a warship grounded years ago by Manila on the contested Second Thomas Shoal that hosts a garrison.

Beijing has continued to press its claims to almost the entire South China Sea despite an international tribunal ruling that its assertion has no legal basis.

China Coast Guard spokesperson Gan Yu said a Philippine vessel had “deliberately collided” with a Chinese ship early Monday.

“Philippine Coast Guard vessels... illegally entered the waters near the Xianbin Reef in the Nansha Islands without permission from the Chinese government,” Gan said, using the Chinese names for the Sabina Shoal and the Spratly Islands.

BEIJING, Aug 19 — Chinese and Philippine vessels collided on Monday during a confrontation near a disputed shoal in the South China Sea, the two countries said.

China and the Philippines have had repeated confrontations in the vital waterway in recent months, including around a warship grounded years ago by Manila on the contested Second Thomas Shoal that hosts a garrison.

Beijing has continued to press its claims to almost the entire South China Sea despite an international tribunal ruling that its assertion has no legal basis.

China Coast Guard spokesperson Gan Yu said a Philippine vessel had “deliberately collided” with a Chinese ship early Monday.

“Philippine Coast Guard vessels... illegally entered the waters near the Xianbin Reef in the Nansha Islands without permission from the Chinese government,” Gan said, using the Chinese names for the Sabina Shoal and the Spratly Islands.

“The China Coast Guard took control measures against the Philippine vessels in accordance with the law,” Gan added.

Manila’s National Task Force on the West Philippine Sea, meanwhile, said two of its coast guard ships were damaged in collisions with Chinese vessels that were conducting “unlawful and aggressive manoeuvres” near the Sabina Shoal.

The confrontation “resulted in collisions causing structural damage to both Philippine Coast Guard vessels”, Manila said.

China claims the Sabina Shoal, which is located 140 kilometres west of the Philippine island of Palawan, the closest major land mass.

Manila and Beijing have stationed coast guard vessels around the shoal in recent months, with the Philippines fearing China is about to build an artificial island there.

‘Dangerous’

Footage purporting to show the incident attributed to the Chinese coast guard and shared by state broadcaster CCTV showed one ship, identified as a Philippine vessel by the Beijing side, apparently running into the left side of a Chinese ship before moving on.

Another 15-second clip appears to show the Chinese vessel making contact with the rear of the Philippine ship.

Captions said the Philippine ship made a “sudden change of direction” and caused the crash.

The Chinese coast guard spokesperson accused Philippine vessels of acting “in an unprofessional and dangerous manner, resulting in a glancing collision”.

“We sternly warn the Philippine side to immediately cease its infringement and provocations,” Gan said.

Manila, however, blamed Beijing, with National Security Council director-general Jonathan Malaya saying the Philippines’ BRP Cape Engano sustained a 13-centimetre hole in its right beam after “aggressive manoeuvres” by a China Coast Guard vessel caused a collision.

A second Philippine coast guard ship, the BRP Bagacay, was “rammed twice” by a China coast guard vessel about 15 minutes later and suffered “minor structural damage”, Malaya said.

The Filipino crew were unhurt and proceeded with their mission to resupply Philippine-garrisoned islands in the Spratly group, he added.

Repeated clashes

Chinese state news agency Xinhua reported that the incident took place at 3:24 am local time.

It also said a Philippine coast guard ship had then entered waters near the Second Thomas Shoal around 6 am.

The shoal lies about 200 kilometres from Palawan and more than 1,000 kilometres from China’s nearest major landmass, Hainan island.

The repeated clashes in the South China Sea have sparked concern that Manila’s ally the United States could be drawn into a conflict as Beijing steps up efforts to push its claims in the sea.

Analysts have said Beijing’s aim is to push eastwards from the Second Thomas Shoal towards the neighbouring Sabina Shoal, encroaching on Manila’s exclusive economic zone and normalising Chinese control of the area.

The situation has echoes of 2012, when Beijing took control of Scarborough Shoal, another strategic area of the South China Sea closest to the Philippines.

— AFP

China accuses the Philippines of deliberately crashing one of its ships into a Chinese vessel

By Associated Press

Aug 19, 2024

China’s coast guard accused the Philippines of deliberately crashing one of its ships into a Chinese vessel early on Monday near Sabina Shoal, a new flashpoint in the increasingly alarming territorial disputes between the countries in the South China Sea.

Two Philippine coast guard ships entered waters near the shoal, ignored the Chinese coast guard's warning and “deliberately collided” with one of China’s boats at 3.24am, a spokesperson said in a statement on the Chinese coast guard's website.

Philippine authorities did not immediately comment on the encounter near the disputed atoll in the Spratly Islands, where overlapping claims are also made by Vietnam and Taiwan.

China’s coast guard accused the Philippines of deliberately crashing one of its ships into a Chinese vessel early on Monday near Sabina Shoal, a new flashpoint in the increasingly alarming territorial disputes between the countries in the South China Sea.

Two Philippine coast guard ships entered waters near the shoal, ignored the Chinese coast guard's warning and “deliberately collided” with one of China’s boats at 3.24am, a spokesperson said in a statement on the Chinese coast guard's website.

Philippine authorities did not immediately comment on the encounter near the disputed atoll in the Spratly Islands, where overlapping claims are also made by Vietnam and Taiwan.

Mischief Reef in the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea. (Getty images)

“The Philippine side is entirely responsible for the collision,” spokesman Gan Yu said.

“We warn the Philippine side to immediately stop its infringement and provocation, otherwise it will bear all the consequences arising from that.”

Gan added China claimed “indisputable sovereignty” over the Spratly Islands, known in Chinese as Nansha Islands, including Sabina Shoal and its adjacent waters.

“The Philippine side is entirely responsible for the collision,” spokesman Gan Yu said.

“We warn the Philippine side to immediately stop its infringement and provocation, otherwise it will bear all the consequences arising from that.”

Gan added China claimed “indisputable sovereignty” over the Spratly Islands, known in Chinese as Nansha Islands, including Sabina Shoal and its adjacent waters.

The Chinese name for Sabina Shoal is Xianbin Reef.

In a separate statement, he said the Philippine ship that was turned away from Sabina Shoal entered waters near the disputed Second Thomas Shoal, ignoring the Chinese coast guard’s warnings.

“The Chinese coast guard took control measures against the Philippine ship in accordance with law and regulation,” he added.

READ MORE: New poll spells dire news for government

Sabina Shoal, which lies about 140 kilometres west of the Philippines' western island province of Palawan, has become a new flashpoint in the territorial disputes between China and the Philippines.

The Philippine coast guard deployed one of its key patrol ships, the BRP Teresa Magbanua, to Sabina in April after Filipino scientists discovered submerged piles of crushed corals in its shallows which sparked suspicions that China may be bracing to build a structure in the atoll.

READ MORE: Sydney Metro trains open doors after a decade of work

In a separate statement, he said the Philippine ship that was turned away from Sabina Shoal entered waters near the disputed Second Thomas Shoal, ignoring the Chinese coast guard’s warnings.

“The Chinese coast guard took control measures against the Philippine ship in accordance with law and regulation,” he added.

READ MORE: New poll spells dire news for government

Sabina Shoal, which lies about 140 kilometres west of the Philippines' western island province of Palawan, has become a new flashpoint in the territorial disputes between China and the Philippines.

The Philippine coast guard deployed one of its key patrol ships, the BRP Teresa Magbanua, to Sabina in April after Filipino scientists discovered submerged piles of crushed corals in its shallows which sparked suspicions that China may be bracing to build a structure in the atoll.

READ MORE: Sydney Metro trains open doors after a decade of work

A member of the Philippine Coast Guard holds flags during the arrival of Chinese naval training ship, Qi Jiguang, for a goodwill visit at Manila's port, Philippines, June 14, 2023. (AP Photo/Basilio Sepe, File) (AP)

The Chinese coast guard later deployed a ship to Sabina.

Sabina lies near the Philippine-occupied Second Thomas Shoal, which has been the scene of increasingly alarming confrontations between Chinese and Philippine coast guard ships and accompanying vessels since last year.

IN PICTURES: TV stars shine on Logies red carpet

China and the Philippines reached an agreement last month to prevent further confrontations when the Philippines transports new batches of sentry forces, along with food and other supplies, to Manila’s territorial outpost in the Second Thomas Shoal, which has been closely guarded by Chinese coast guard, navy and suspected militia ships.

The Philippine navy transported food and personnel to the Second Thomas Shoal a week after the deal was reached and no incident was reported, sparking hope that tensions in the shoal would eventually ease.