Official US Poverty Rate Declined in 2023,

But More People Faced Economic Hardship

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

The number of Americans living in poverty, according to the nation’s official definition, fell slightly to about 36.8 million in 2023, the Census Bureau announced on Sept. 10, 2024. The data released also indicated that the poverty rate declined a little. However, an alternative way to measure poverty ticked up, as more people in the U.S. faced economic hardship.

Mark Rank, a sociologist who researches poverty and economic inequality, explains the latest numbers and shares some of his insights about poverty in America.

What’s the most significant news?

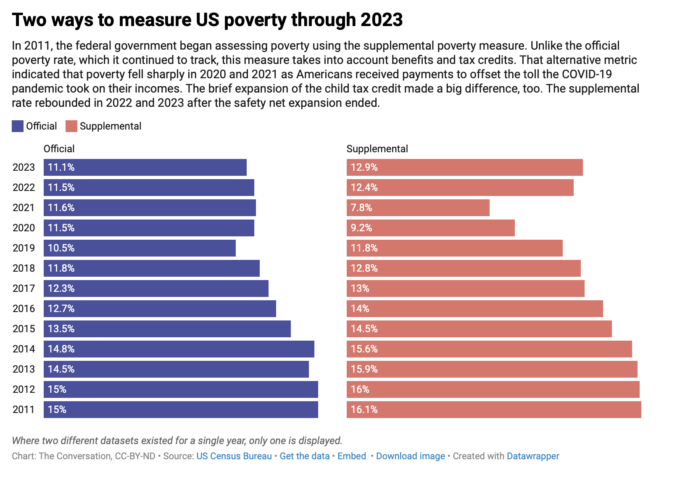

I think the most interesting aspect of this report is the different directions the two measures of poverty went in 2023. On one hand, the official poverty measure declined to 11.1% in 2023 from 11.5% in 2022. At the same time, the supplemental poverty measure, an alternative way to measure poverty introduced in 2011, increased to 12.9% in 2023 from 12.4% a year earlier.

The official poverty rate fell because overall household income rose modestly in 2023 – even after taking inflation into account – according to other census data. However, like many poverty experts, I believe that the supplemental poverty measure is a better indicator of what’s going on because it takes into account household expenses as well as tax credits and the effects of government programs on reducing poverty.

It turns out that one key reason for the increase in the current supplemental poverty measure is that Social Security benefits and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – also known as SNAP or “food stamps” – pulled fewer people out of poverty in 2023 than in 2022.

The supplemental poverty measure also increased as the result of out-of-pocket medical expenses being higher in 2023 than in 2022.

Are there more meaningful ways to assess poverty in America?

The annual Census Bureau report only represents a year-by-year snapshot of poverty. I think estimating the long-term risk of impoverishment across a typical American’s lifetime is a more meaningful approach.

To that end, I’ve conducted research using a large nationally representative dataset from University of Michigan researchers who have tracked the same households each year since 1968. Based on this analysis, I’ve found that a clear majority of Americans will experience poverty for at least one year of their adult lives.

Some 58.5% of Americans will experience at least one year below the official poverty line between the ages of 20 and 75, while 76% will either experience poverty or near poverty – meaning that their income falls below 150% of the poverty line.

The numbers presented in the annual Census Bureau report indicate that only about 1 in 9 Americans are facing poverty today. But my research shows that 3 out of 4 Americans will experience poverty or near poverty at some point in their lives. The result is that poverty should be viewed as an issue of “us” rather than an issue of “them.”

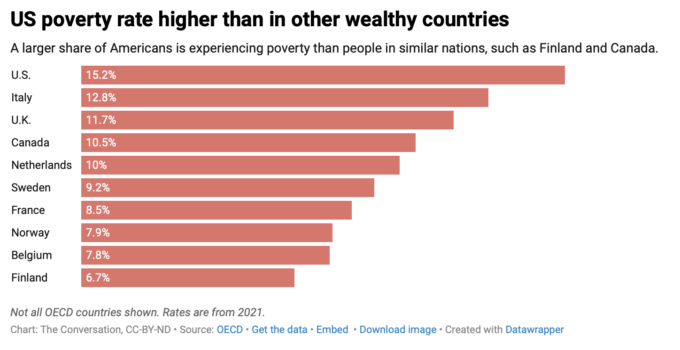

How does poverty in the US compare with what’s going on in similar economies?

The U.S. has one of the highest rates of poverty among Western industrialized nations. Whether the focus is on working-age adults, children, people over 65 or the population as a whole, the U.S. is near the top in terms of the extent and depth of its poverty.

One major reason is that the federal government does much less than its counterparts in many other countries to help people stay out of poverty. The U.S. safety net is relatively weak when it comes to protecting Americans from economic destitution.

The result is that the percentage of Americans experiencing poverty in any given year is among the highest among comparable nations.

In addition, the extent of both income and wealth inequality tends to be more extreme in the U.S. compared with other high-income countries.

How do you interpret the long-term patterns in the US poverty rate?

The U.S. made substantial progress in terms of reducing poverty in the middle of the 20th century. The poverty rate was cut in half from 22.4% in 1959 to 11.1% in 1973.

This improvement was due to the robust economy of the 1960s and government initiatives known as the “War on Poverty.” However, since 1973, the overall rate of poverty has ranged between 11% and 15%. It has tended to decline somewhat during periods of economic growth, and it has risen during periods of economic stagnation and recession.

The official poverty rate of 11.1% in 2023 matches the poverty rate in 1973. The supplemental poverty measure, which stood at 12.9% in 2023, reflects a similar lack of progress. It was first calculated in 2009, when it stood at 15.1%.

There are two major success stories, however.

First, older Americans have become less likely to experience poverty.

In 1959, 35.2% of people who were 65 and up were experiencing poverty – the highest rate of any age group. In 2023, only 9.7% of older Americans were in poverty, as indicated by the official rate, and that was among the lowest for any age group.

The primary reason for this reduction was the expansion of Social Security benefits and the introduction in 1965 of the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Without these programs, poverty for older Americans would rise to an estimated 40%.

The other major success story was that the share of U.S. children experiencing poverty fell substantially in 2021 as a result of the child tax credit expansion and the economic impact payments the federal government made to all Americans beginning in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked economic havoc.

As a result of these policies and others, the supplemental poverty measure among children fell by nearly half to 5.2% in 2021, from 9.7% in 2020. With the expiration of these benefits, the rate of childhood poverty has returned to pre-pandemic levels. According to the supplemental poverty measure, it rose to 13.7% in 2023 – the highest rate since 2018.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.