Urged on by Conservatives and His Own Advisers, Trump Targeted the WHO

Trump cuts WHO funding in concerted efforts with conservatives and allies

Michael D. Shear, The New York Times•April 16, 2020

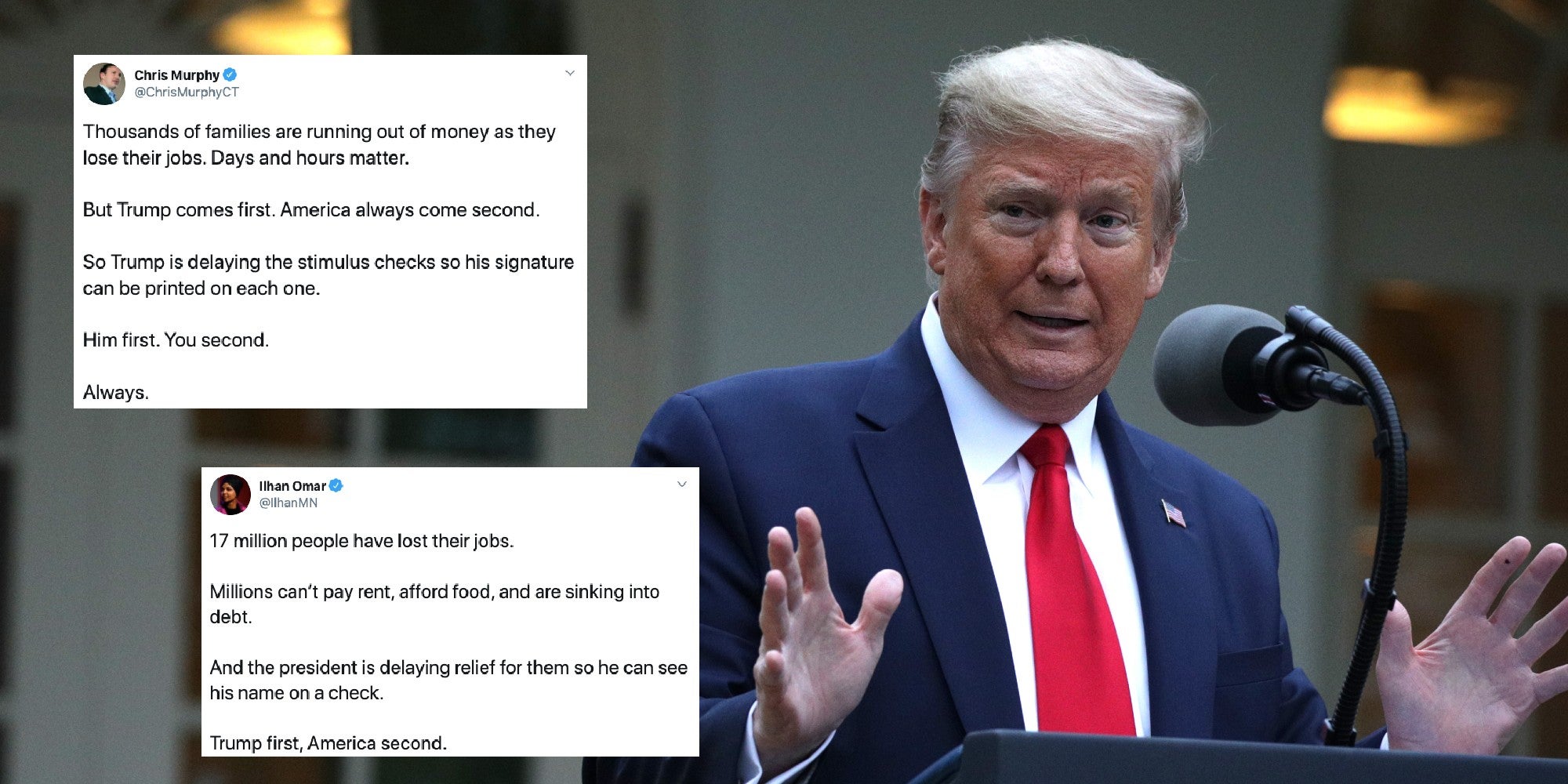

WASHINGTON — Fox News pundits and Republican lawmakers have raged for weeks at the World Health Organization for praising China’s handling of the coronavirus crisis. On his podcast, President Donald Trump’s former chief strategist, Stephen Bannon, urged his former boss to stop funding the WHO, citing its ties to the “Chinese Communist Party.”

And inside the West Wing, the president found little resistance among the China skeptics in his administration for lashing out at the WHO and essentially trying to shift the blame for his own failure to aggressively confront the spread of the virus by accusing the world’s premier global health group of covering up for the country where it started.

Trump’s decision Tuesday to freeze nearly $500 million in public money for the WHO in the middle of a pandemic was the culmination of a concerted conservative campaign against the group. But the president’s announcement on the WHO drew fierce condemnations from many quarters.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce said cutting its funding was “not in U.S. interests.” Speaker Nancy Pelosi called the decision “dangerous” and “illegal.” Former President Jimmy Carter said he was “distressed,” calling the WHO “the only international organization capable of leading the effort to control this virus.”

Founded in 1948, the WHO works to promote primary health care around the world, improve access to essential medicine and help train health care workers. During emergencies, the organization, a United Nations agency, seeks to identify threats and mitigate the risks of dangerous outbreaks, especially in the developing world.

In recent years, the United States has been the largest contributor to the WHO, giving about $500 million a year, though only about $115 million of that is considered mandatory as part of the dues that Congress agreed to pay as a member. The rest was a voluntary contribution to combat specific health challenges like malaria or AIDS.

How Trump’s order to freeze the group’s funding while officials conduct a review of the WHO would be carried out was not clear. Congressional Democrats who oversee foreign aid said they did not believe Trump had the power to unilaterally stop paying the nation’s dues to the WHO. Congressional aides cited a Government Accountability Office report in January that concluded that the administration could not simply ignore congressionally directed funding for Ukraine simply because Trump wanted to.

A senior aide to House Democrats said they were reviewing their options in the hopes of keeping the money flowing. But Democrats conceded that Trump most likely has wide latitude to withdraw the voluntary contributions to specific health programs run by the WHO.

White House officials say Trump was moved to act in part by his well-known anger about sending too much of the public’s money to international organizations like NATO and the United Nations. And they said he agreed with the criticism that the WHO was too quick to accept China’s explanations after the virus began spreading.

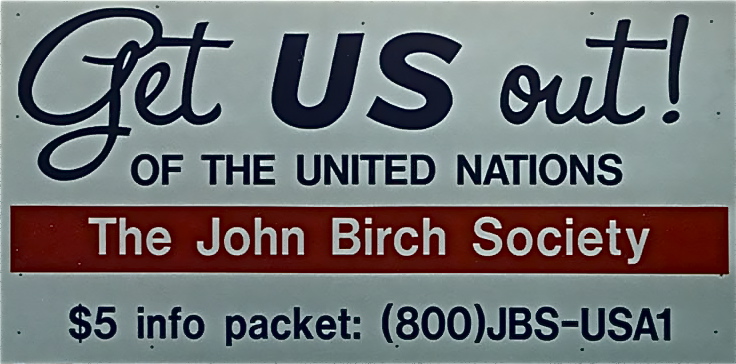

JOHN BIRCH SOCIETY

They cited a Twitter post by the WHO on Jan. 14 saying that the Chinese government had “found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the novel #coronavirus” as evidence that the WHO was covering up for China. And they noted that in mid-February, a top official at the WHO praised the Chinese for restrictive measures they insisted had delayed the spread of the virus to other countries, saying, “Right now, the strategic and tactical approach in China is the correct one.”

“It is very China-centric,” Trump said in announcing his decision Tuesday in the Rose Garden.

“I told that to President Xi,” he said, referring to Xi Jinping of China. “I said, ‘The World Health Organization is very China-centric.’ Meaning, whatever it is, China was always right. You can’t do that.”

Public health experts say the WHO has had a mixed record since the coronavirus emerged in late December.

The health organization raised early alarms about the virus, and Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the group’s director-general, held almost daily news briefings beginning in mid-January, repeating the mantra, “We have a window of opportunity to stop this virus. But that window is rapidly closing.”

But global health officials and political leaders — not just Trump — have said the organization was too willing to accept information supplied by China, which still has not provided accurate numbers on how many people were infected and died during the initial outbreak in the country.

On Wednesday, Scott Morrison, the prime minister of Australia, called it “unfathomable” that the WHO had issued a statement supporting China’s decision to allow the reopening of so-called wet markets, the wildlife markets where the virus is believed to have first spread to humans. And in Japan, Taro Aso, the deputy prime minister and finance minister, recently noted that some people have started referring to the WHO as the “Chinese Health Organization.”

But defending the WHO on Wednesday, Dr. Michael Ryan, executive director of its emergencies programs, cited the early warning it sounded. “We alerted the world on January the 5th,” Ryan told reporters.

Ghebreyesus expressed disappointment with Trump’s decision to freeze funding.

“WHO is not only fighting COVID-19,” he said. “We’re also working to address polio, measles, malaria, Ebola, HIV, tuberculosis, malnutrition, cancer, diabetes, mental health and many other diseases and conditions.”

THE ORIGIN OF ANTI-VAXING IS ANTI-COMMUNIST AMERICAN FASCISM

“It is very China-centric,” Trump said in announcing his decision Tuesday in the Rose Garden.

“I told that to President Xi,” he said, referring to Xi Jinping of China. “I said, ‘The World Health Organization is very China-centric.’ Meaning, whatever it is, China was always right. You can’t do that.”

Public health experts say the WHO has had a mixed record since the coronavirus emerged in late December.

The health organization raised early alarms about the virus, and Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the group’s director-general, held almost daily news briefings beginning in mid-January, repeating the mantra, “We have a window of opportunity to stop this virus. But that window is rapidly closing.”

But global health officials and political leaders — not just Trump — have said the organization was too willing to accept information supplied by China, which still has not provided accurate numbers on how many people were infected and died during the initial outbreak in the country.

On Wednesday, Scott Morrison, the prime minister of Australia, called it “unfathomable” that the WHO had issued a statement supporting China’s decision to allow the reopening of so-called wet markets, the wildlife markets where the virus is believed to have first spread to humans. And in Japan, Taro Aso, the deputy prime minister and finance minister, recently noted that some people have started referring to the WHO as the “Chinese Health Organization.”

But defending the WHO on Wednesday, Dr. Michael Ryan, executive director of its emergencies programs, cited the early warning it sounded. “We alerted the world on January the 5th,” Ryan told reporters.

Ghebreyesus expressed disappointment with Trump’s decision to freeze funding.

“WHO is not only fighting COVID-19,” he said. “We’re also working to address polio, measles, malaria, Ebola, HIV, tuberculosis, malnutrition, cancer, diabetes, mental health and many other diseases and conditions.”

THE ORIGIN OF ANTI-VAXING IS ANTI-COMMUNIST AMERICAN FASCISM

JOHN BIRCH SOCIETY

Trump’s decision to attack the WHO comes as he is under intense fire at home for a failure to respond aggressively to the virus, which as of Wednesday had claimed more than 28,000 lives and infected at least 600,000 people in the United States.

The president publicly shrugged off the virus throughout January and much of February, repeatedly saying that it was under control. He said in mid-February that he hoped the virus would “miraculously” disappear when the weather turned warm.

Trump barred some travel from China in late January, a move that health experts say helped delay widespread infection. But he also presided over a government that failed to make testing and medical supplies widely available and resisted calling for social distancing that allowed the virus to spread for several critical weeks.

The president’s decision to freeze the WHO funding was backed by many of his closest aides, including Peter Navarro, his trade adviser, and key members of the National Security Council, who have long been suspicious of China. Trump himself has often offered contradictory messages about the country — repeatedly saying nice things about Xi even as he wages a fierce on-again, off-again trade war with China.

“China has been working very hard to contain the Coronavirus,” Trump tweeted Jan. 24. “The United States greatly appreciates their efforts and transparency.”

At a meeting of his coronavirus task force Friday, Trump polled all the doctors in the room about the WHO, according to an official who attended the meeting. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, said that the WHO had a “China problem,” and then others around the room — including Dr. Deborah Birx, who is coordinating the U.S. response, and Dr. Robert Redfield, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — agreed with the statement, the official said.

But the president’s critics assailed the timing of the announcement, saying that any assessment of the WHO should wait until the threat was over.

JOHN BIRCH SOCIETY

Among those questioning the president’s decision to act now was Redfield, who heaped praise on the WHO during an appearance Wednesday on “CBS This Morning,” saying that questions about what the group did during the pandemic should be left until “after we get through this.” He said that the WHO remained “a long-standing partner for CDC,” citing efforts to fight the Ebola virus in Africa and the cooperation to limit the spread of the coronavirus. And he added that the United States and the WHO have “worked together to fight health crises around the world — we continue to do that.”

Pelosi said Trump was acting “at great risk to the lives and livelihoods of Americans and people around the world.” And in its statement, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce said that it supported reform of the WHO but that “cutting the WHO’s funding during the COVID-19 pandemic is not in U.S. interests given the organization’s critical role assisting other countries — particularly in the developing world — in their response.”

In a tweet, Bill Gates, founder of Microsoft and later a global health foundation, said the decision to end funding “during a world health crisis is as dangerous as it sounds.”

He added, “Their work is slowing the spread of COVID-19 and if that work is stopped no other organization can replace them. The world needs @WHO now more than ever.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2020 The New York Times Company