Coronavirus global slowdown is cleaning the skies. How long will it last?

The coronavirus pandemic has produced startling images, not just of besieged emergency rooms, but of deserted highways, beaches, and other public places—of life interrupted everywhere.

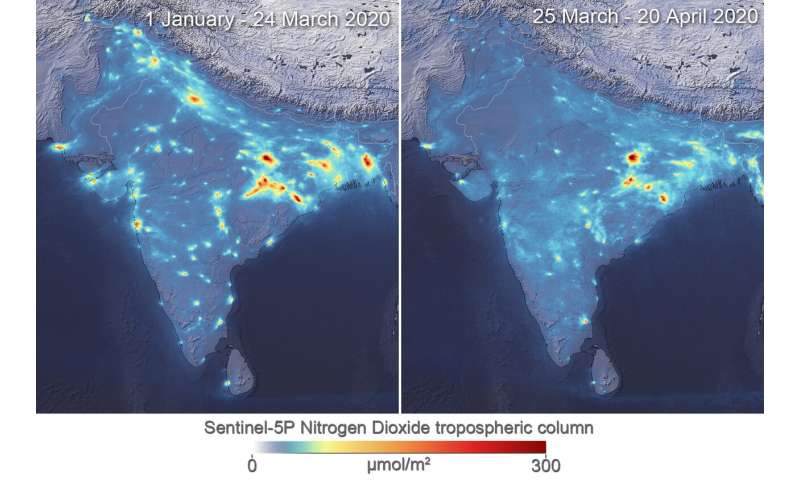

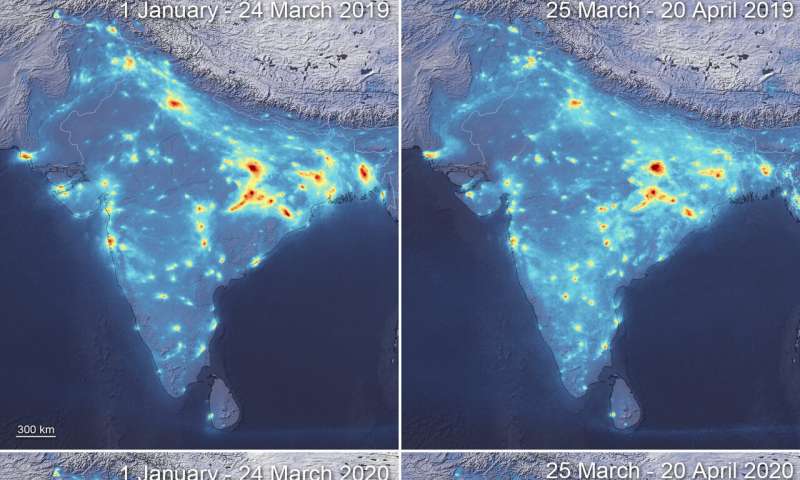

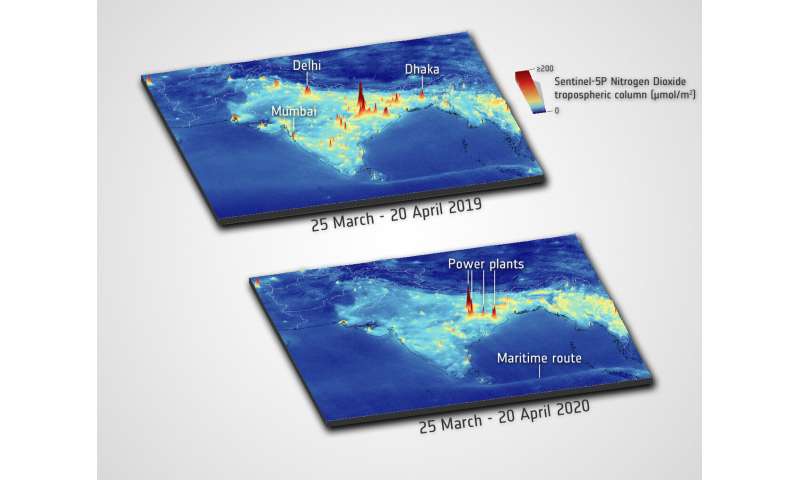

The economic effect produced other surreal images in the run up to Earth Day that hint at what could either be a new normal or mere apparition: jellies swimming through Venice canals, blue skies over urban skylines normally tinted brown year-round. In India, people living at the feet of the Himalayas have been able to see the mountains for the first time in years, as if in a dream."

These will be among the immediate effects of coronavirus, say scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego who have been monitoring pollution, tracking the chief greenhouse gas carbon dioxide, and documenting ecosystem responses. While lamenting the terrible circumstances that have led to various changes in nature, they predict CO2 levels will show a slight drop if economic activity is slowed for a full year, air pollution will be expected to kill fewer people, and fishes that would have been caught as seafood will instead live another season to reproduce. That will improve fish stocks and the overall health of the oceans now that fishing vessels are, by and large, docked.

But what is more debatable is whether things return to normal or not after all this, they say. After this tragedy-induced alteration of life is declared over, what is left is a public mindset now open to re-scripting.

Climate scientist Veerabhadran Ramanathan spent much of his career documenting the effect that pollutants other than carbon dioxide have on global warming. He defined the composition and size of large masses of persistent air pollution filled with black carbon soot and other harmful compounds that form around the world. More than a decade ago, he began Project Surya to see what would happen—to climate and to public health—if local cooking practices in pockets of his native India could be made cleaner. Now, it is as if the Project Surya study area has expanded to include all of South Asia.

"We would hope that the evidence drives public support for drastic climate actions such as a zero-emission carbon-free economy," said Ramanathan, who is co-author of Bending the Curve: Climate Change Solutions. "The climate crisis can be solved if we quickly cut super pollutants such as soot, while also pursuing transition to clean energy worldwide."

Scripps Oceanography geochemist Ralph Keeling maintains the Keeling Curve, a record of carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere begun by his late father, Charles David Keeling, in 1958. Those levels have steadily risen save for a few blips over the years such as the collapse of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and the 2008 recession. All such fleeting downturns have revived after periods of months to rise with renewed ferocity, said Keeling. If this episode slows down economic activity by 10 percent for a full year, that would translate to about a 0.5 percent drop in carbon dioxide levels.

In the scheme of climate change, Keeling said what is happening now might be hard to evaluate.

"It's like turning down the tap on a bathtub. You can see the tap is turned down just by looking at it," he said. "But it takes a while to notice that the tub is filling more slowly."

But what could last is a change in the way people live. Telecommuting could become more accepted by many employers some of whose operations have continued with only minimal disruptions as employees work from home. Keeling noted in a recent interview that the current crisis has shown society "how we can live differently if we have to."

Keeling and Scripps Oceanography colleague Ray Weiss are part of the L.A. Megacities project, a multi-institutional attempt to isolate the greenhouse gas emissions of metropolitan areas. Megacities researchers monitor Los Angeles and Paris at the moment. Weiss said that Los Angeles is indeed registering signs of a change in lifestyle at first glance, though the nuances of the coronavirus effect will take longer to tease out. Carbon monoxide, a pollutant specific to vehicles more than any other, has been precipitously falling since March, the time of year when levels typically begin to increase. Heavy March rains also helped clean the air so determining the relative influences will take time.

Jeremy Jackson, an emeritus professor of oceanography at Scripps, spent much of his career documenting how natural systems decline and how perceptions of what is normal in nature deteriorate over generations. The concept is known as "shifting baselines." For instance, one might see a dozen sharks in a square mile of ocean and conclude the ocean is healthy though there might have been 500 sharks in that same area several hundred years ago before human intrusion.

Jackson sees the global economy not being where it was pre-coronavirus for up to five years–even if a vaccine were to be available next week. There will be a lingering fear of large gatherings, of getting on airplanes, of eating at restaurants, imprinted even after restrictions are lifted. Though not worth the tragedy that precipitates it, the pandemic will effect substantial change, he said.

"It's not an exaggeration to say that if air quality is good for one year, 100,000 people will not die unnecessarily," he said.

Americans are realizing, for instance, their reliance on goods that come from far away and are beginning to see value in reasserting control over their supply chains. People in Maine, where Jackson currently lives, are sourcing their lettuce from local greenhouses now that deliveries from California are disrupted. That change in consumer habits might endure even after delivery trucks are rolling again.

"The notion that we don't care where in the world something comes from is over," he said.

But the most lasting outcome might be that this generation will adopt the mentality of people who lived through the Great Depression, he said.

"What this is doing is forcing us to be more introspective in our lives," said Jackson. "I think there will be a mental evolution of our society, one that's more cautious and conservative of our resources."

Weiss does not hold out great hope for the wholesale lifestyle changes that need to happen for global warming to permanently attenuate. He sees emissions returning to full strength once the economy does. He does have a more modest hope that one effect will live on even when life turns back to normal.

"The only silver lining I'm hoping for is that this may help the public listen again and have respect for the value of science," he said.