State Papers 1990: Joe Biden motion on Birmingham Six added to growing pressure on UK

President-elect Joe Biden speaks at The Queen Theater in Wilmington, Del., Tuesday, Dec 22, 2020. Picture: AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster

SUN, 27 DEC, 2020 -

SEAN MCCARTHAIGH

IRISH EXAMINER

A resolution proposed by US president-elect, Joe Biden, in March 1990 on the Birmingham Six while a US senator added to growing pressure on the British government to re-examine the group’s conviction for the largest ever IRA bomb attack in Britain.

State papers released under the 30-year rule by the National Archives show a Department of Foreign Affairs memo listing Biden’s intervention as one example of mounting international action seeking a fresh inquiry on the case.

Biden, who had unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination to contest the 1988 US presidential election two years earlier, was the second-ranking Democrat on the US Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee at the time.

The resolution proposed by Biden on March 9, 1990, which secured 13 co-sponsors including other leading Irish-American politicians, Senators Edward Kennedy and Patrick Moynihan, called for a re-opening of the case and for US president, George Bush, to raise it with the British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher

.

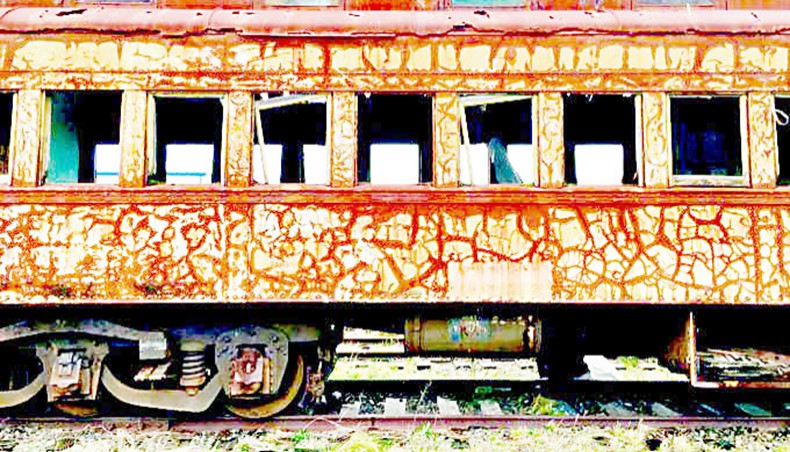

The Birmingham Six outside the Old bailey in London, after their convictions were quashed.

Left-right: John Walker, Paddy Hill. Hugh Callaghan, Chris Mullen MP, Richard McIlkenny,

Gerry Hunter and William Power.

It was similar to a motion that had been tabled by US Congressman and chairman of the Friends of Ireland, Brian Donnelly, two months earlier which also called for the quashing of the convictions.

The Department of Foreign Affairs said it understood that the British Embassy in Washington had actively lobbied against the motion.

The Birmingham Six – Hugh Callaghan, Gerard Hunter, Paddy Hill, John Walker, Richard McIlkenny and William Power – were sentenced to life imprisonment in 1975 for two IRA bomb attacks on pubs in Birmingham on November 21, 1974 which killed 21 people.

Their convictions were based on forensic evidence and confessions that were contested from the outset of the case.

A newsletter published by the Birmingham Six Committee in April 1990 noted that Donnelly’s motion was “more radical” than Biden’s

.

Staff photographer Denis Minihane's picture of the Birmingham Six

following their release at the Old Bailey in London.

However, Paddy McIlkenny, Richard’s brother, who had campaigned for the group’s release, said the support of leading US politicians in early 1990 had given an important boost to their campaign and said the two resolutions by Biden and Donnelly would generate more publicity when they were debated in the US Congress and Senate.

“That will be very embarrassing for the British Government,” McIlkenny said.

A short time later, the British Home Office ordered a fresh police inquiry into the case following the submission of new evidence by the men’s solicitor, Gareth Peirce, which subsequently led to it being referred to the Court of Appeal for a second full hearing.

McIlkenny admitted being sceptical about the outcome of the police review as he believed its announcement was timed to defuse mounting pressure from the US.

The convictions of the Birmingham Six were finally declared unsafe and quashed by the Court of Appeal in March 1991.