Back to the Future of the Arctic

The Enduring Relevance of Arms Control

SWP Comment 2024/C 18,

Michael Paul02.05.2024,

7 Pages

doi:10.18449/2024C18

doi:10.18449/2024C18

Research Areas

Security and defence policy

PDF | 318 KB

EPUB | 1.2 MB

MOBI | 2.9 MB

Russia’s war against Ukraine seems to have no immediate end in sight, the strategic competition between China and the US continues, and the expanding military cooperation between China and Russia increases the challenges facing the international community. In this context, the Arctic seems to be a relic of the past, no longer the “zone of peace” that Mikhail Gorbachev described in 1987. Indeed, this Arctic exceptionalism ended long before Russia’s war of aggression began. In order to restore at least a minimum level of cooperation, informal talks are needed that could help to provide perspective after the end of the war. Two former relatively uncontroversial projects could serve as starting points: the recovery of radioactive remnants of the Cold War and an agreement to prevent unintentional escalation, namely, another Incidents at Sea Agreement (INCSEA). A return to old approaches to arms control could pave the way to renewed cooperation in the Arctic in the future.

Generalised mistrust has supplanted the trust that once anchored the Arctic Council, and it is difficult to see at what level and by what means the forum can be brought back to constructive engagement. Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia has now either violated or terminated all remaining arms control agreements and fora. Trusting cooperation with Putin is no longer possible, and his aggressive, neo-imperialist policy will have a lasting impact. Yet, Russia still laments the loss of trust – as cynical as this may sound in view of the ongoing brutality of Russian warfare and violations of international law.

Reinstatement of the Arctic as an area of cooperation and stability is the long-term goal of all member states of the Arctic Council. Indigenous peoples and observer states, including Germany, are also likely to agree on this. Even Moscow seems to be interested in some kind of stability, particularly to enable the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation (AZRF) to function as its national resource base funded by foreign investments and thus to reduce its growing dependence on China. However, Russia currently remains on a collision course with the West. The hostilities in Ukraine will not end in 2024, which will be a decisive year in many respects; a historic NATO summit will take place in Washington and several elections will occur, including the US presidential elections in November.

In order to make future cooperation possible, it is advisable to reflect critically on certain measures that appear suitable to restore trust in the intentions and goals of Arctic actors. To this end, the original objectives and instruments of arms control should be reconsidered, and thought should be given to how they can be applied within the new Arctic security environment. This applies across the entire spectrum, from confidence-building measures to arms control of weapons systems.

The Arctic: a hotspot of climate change and an area of political opportunity

The Arctic is a good starting point for unofficial talks and an eventual resumption of positive diplomatic exchange, not least because of its geographic location far from current geopolitical hotspots in the Sino-American rivalry and its increasing importance for both China and the United States. According to Canadian political scientist Rob Huebert, the US, China, and Russia form “a new Arctic strategic triangle” which essentially determines the potential for conflict in the Arctic.

The effects of climate change in combination with strategic competition form a toxic mix when it comes to cooperation among the Arctic players. Due to continued warming, an ice-free Arctic Ocean will likely become a reality in the near future. In this case, the Arctic Ocean is expected to be covered by less than 15 percent sea ice in the summer months. Such a scenario is now foreseen to occur by the mid-2030s, whereas some time ago this was not expected until the middle or end of the century. Due to this development, sea routes and resources in the Arctic will be more accessible soon. Civilian and military activities are already growing and competition for access and influence in the Arctic is intensifying. This has created a need for rules governing states’ behaviour, while also taking into account transnational and indigenous relationships.

The increase of military activity requires arms control in the original and comprehensive sense. This means that potential adversaries should engage in all forms of military cooperation in the interest of reducing the probability, scale, and violence of a potential military conflict, as well as the political and economic costs of preparing for one. In this context, it is now a question of what can be used in the medium term to overcome the ongoing tensions and to shape mutually beneficial cooperation in the Arctic in the future. A certain degree of cooperation with Russia is necessary in order to avoid misunderstandings, miscalculations, and mutually undesirable events which could occur in the context of military activities. In the long term, stability is a prerequisite to the sustainable use of Arctic sea routes and resources. The Arctic states will need to involve new players such as China if a “peaceful, stable, prosperous and cooperative Arctic” is to be possible in line with the US Arctic strategy.

Such a constructive approach currently has little chance of success within Russia, as with many NATO states. The Kremlin sees the collective West as an opponent and perceives willingness to negotiate as a weakness. Within NATO, the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine has strengthened internal cohesion, but the alliance is not united on the question of how security should be guaranteed against Russia in the future. The opinion in many NATO states is that Russia can only be countered from a position of strength, which thus requires comprehensive rearmament. Others, on the other hand, also consider risk reduction measures to be reasonable, which would require a minimum level of cooperation. A clear decision on NATO’s political direction is not expected before this year’s summit in Washington and the US presidential election.

First and foremost, it is necessary to reach a common understanding of how future relations with Russia should be shaped after the end of the war against Ukraine. The Arctic is of central importance to Russia not only as a national resource base and sea route, but also as a zone of security that guarantees Russia’s maritime nuclear second-strike capability. For their part, the northern European states, as well as the US and Canada, are facing new types of military threats that require novel concepts and costly investment in capacities. Former concepts such as crisis stability are being challenged by the emergence of hypersonic weapons systems, and this puts political decision-making processes under even more pressure.

The security dilemma in the Arctic should be defused, the build-up of military capabilities contained, and crisis and conflict prevention measures should be introduced. Ideally, these goals can serve as building blocks for a future security architecture. Otherwise, the increasing activities in the Arctic – from civilian shipping to large-scale military exercises – exacerbate the risk of unintentional escalation as a result of misunderstanding or misperception. Thus, a dialogue on military security issues in the Arctic must be established.

At which level could the Arctic states resume dialogue?

Despite tensions with Russia, communication between the Arctic states continues, both at an official level, such as within the framework of the United Nations, and bilaterally insofar as it is enshrined in agreements that regulate border traffic, protect fishing activities, and maintain search and rescue commitments. Multilateral formats are also still active, for example among parties to the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement (CAOFA).

However, a security dialogue that includes Moscow and focuses explicitly on the Arctic no longer exists. Since its annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia is no longer involved in dialogue among the Arctic states’ military commanders (the Arctic Chiefs of Defence [ACHOD]) or in the annual meetings of the Arctic Security Forces Roundtable (ASFR). Germany, France, the UK, and the Netherlands are also represented at the ASFR. Other formats of which Russia is a member such as the Arctic Council and the Arctic Coast Guard Forum (ACGF) do not address military security, nor does the Barents Euro-Arctic Council, from which Russia withdrew in September 2023. Even before the war, experts widely agreed that Russia needed to be reincluded in dialogue, but opinions differ among politicians and experts as to how this should be done.

The most obvious solution seems to be the least realistic, namely extending the mandate of the Arctic Council to include military affairs. Indeed, the Arctic Council has a high degree of institutionalisation and has been successfully active for over two decades. The extension of its mandate would therefore appear to be easier than creating an entirely new format as it also already brings together all of the main regional players. In spite of this, member states would need to agree on broadening the Council’s mandate to include military security issues, and this has already been rejected by some members. While Iceland’s Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir and Finland’s Prime Minister Antti Rinne spoke out in favour of such a solution in the past, others voiced concerns that this could hinder cooperation. Former Norwegian Arctic envoy Bård Ivar Svendsen, for example, noted at a time of extensive cooperation that the dialogue with Russia in the Council only remained active precisely because security policy was not being discussed. Moreover, in 2021, Alaska’s Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) President Jimmy Stotts refused to address defence issues, stating, “[w]e don’t wish to see our world overrun with other peoples’ problems”. Consensus on this front therefore remains unlikely.

Another approach would be to resort to already established formats. For instance, in the beginning of Russia’s chairmanship of the Arctic Council (2021-23), Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov sought to reactivate dialogue between the general staffs of the Arctic states. With this in mind, Russia’s Arctic ambassador Nicolay Korchunov declared his intention to resume informal exchanges between military experts from the Arctic states. The war against Ukraine has put an end to these ideas, and the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO shows the need for an alternative interim approach aside from formats such as the ACHOD and ASFR that exclude Russia.

Even if scepticism is warranted, dialogue with Russia at an informal, expert level (Track 2) seems reasonable. This would make it possible to test potential approaches to confidence-building measures and, building on this, to initiate official talks at a formal level (Track 1) in due course. Informal talks are an instrument that stimulates reflective dialogue between actors in conflict, especially when discussions at official levels are difficult or even impossible. In today’s new mistrustful and competitive reality, it is important to restore a minimum level of stability. Dialogue between military experts from all eight Arctic states could constitute a new interim format and initiate a process in which confidence-building measures are developed.

To this end, the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) has had experience organising Track 2 (informal) and Track 1.5 (with officials) meetings with Russian representatives before the invasion of Ukraine. Russia has a very limited pool of experts who have little or no exchange with or influence over Russian policy- and decision-making. Since the beginning of the war, the Russian expert community has split into several groups: The first group has fled the country in exile; the second group is still in Russia, but is isolated and trying to fly under the radar; the third group is making a career for themselves by adopting or echoing the Kremlin’s rhetoric. Even if exchange with the second group could be constructive, these (former) experts would be putting themselves at extreme risk by engaging. Interrogations at the borders are commonplace and these experts can easily be declared foreign agents. Track 2 activities are also known to have been infiltrated by Russian intelligence services; and even in cases in which Moscow has authorised such talks (such as the 1993–2013 Armed Forces Dialogue seminars with Russia, organised by SWP in cooperation with the German Federal Ministry of Defence), no significant breakthroughs have truly been witnessed.

With this in mind, informal talks on arms control and transparency measures represent another possible realm of engagement that does not necessarily require mutual trust in order to be successful. Rather, such measures are a means of enabling predictable behaviour among parties who distrust one another and of creating trust in the long-term.

What kind of measures can restore trust?

Trust always involves a degree of uncertainty and the possibility of disappointment. Nevertheless, it also opens up more possibilities for action because, as the sociologist Niklas Luhmann puts it, “trust provides a more effective form of reducing complexity”. Those who act with confidence are optimistic about the future, which always contains a multitude of certain and uncertain events. If calculated rationally, risks cannot be eliminated, but they can be reduced. According to Luhmann, such points of reference can thus serve as a “stepping stone for jumping into a limited and structured uncertainty”.

According to its National Security Strategy, the German government “supports strategic risk reduction and the fostering of predictability, as well as the maintenance of reliable political and military channels of communication in relations between NATO and Russia. [It] remain[s] open to reciprocal transparency measures where the prerequisites for them exist”. This includes the development of new approaches based on behavioural arms control that can help reduce tensions.

In 2023, Russia’s Arctic ambassador Nicolay Korchunov once again expressed the desire for comprehensive cooperation that included military issues, stating that “[i]t can all be sorted out by dialogue, which would strengthen trust”. Despite this sentiment, it will be difficult to start a dialogue in view of the consequences of the war in Ukraine. Russia’s current policy gives little hope for constructive talks, as deliberately playing with unpredictability is one of Russia’s manipulation tactics to destabilise Western societies and institutions. This, however, should not prevent preparations and considerations with respect to how security and stability can be enhanced in the future.

Confidence-building measures (CBMs) should define acceptable and legitimate behaviour. They should help to promote transparency and reduce the risk of misjudgements, and hence, unwanted escalation. In this way, a certain degree of crisis stability and trust in the intentions of the other side can be fostered. This could mitigate the current security dilemma.

CBMs could, for example, focus on creating transparency with regard to military activities, and they could incorporate recommendations from the former NATO-Russia expert dialogue. For instance, Arctic military bases could be subject to mutual visits. A regular regiment on visitation could be established and plans for military exercises could be disclosed. Advance notice of Russian exercises could help to avoid misinterpretation. In turn, NATO allies could inform Russia about unscheduled activities.

Confidence- and security-building measures (CSBMs) are rooted in the Vienna Document on CSBMs. In the 1990s, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) created the world’s most advanced set of rules for arms control, verification, and CBMs. Now many of the agreements under this arrangement have either been suspended or weakened as partners withdraw. According to OSCE Secretary General Helga Maria Schmid, however, this does not mean that CSBMs will not play an important role again in the future, as the instruments are still available.

New dialogue requires constructive substance in the form of suitable projects that foster cooperation. In the long term, it is important to develop a new set of (multilateral) rules that serve both sides’ interests. According to a team of authors from the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt, two basic conditions must be met to facilitate an effective multilateral agreement: The rules must be designed so that they are appropriate for solving the problems and these rules must be adhered to by the involved states. Accordingly, the crucial question is to what extent these rules will restrict state action, including military action.

Potential cooperation projects

The oldest CSBM to prevent unintentional escalation is the Incidents at Sea Agreement (INCSEA), concluded between the US and the Soviet Union in 1972. Individual NATO states such as Norway have continued similar agreements with Russia, taking into account new technological developments. All contain similar provisions that can be qualified as CSBMs. While bilateral INCSEA agreements between states with naval forces operating worldwide make sense, a multilateral Arctic INCSEA agreement or a NATO-Russia INCSEA agreement that would apply to all naval ships in the Arctic Ocean would be more purposeful. In practice, it would be easier for navy officers to work with a single set of signals than with many different ones, as noted by a RAND study. This would also mirror considerations for a similar agreement between the US and China in the Western Pacific.

Further rules of conduct, such as a Arctic Military Code of Conduct, have long been discussed. One possible model is the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement, which provides a format for negotiations between the Arctic’s coastal states, four countries engaging in fishing activities in the Arctic, and the EU. In addition to the Arctic states, a military code of conduct could also include countries that are capable of military operations in the Arctic. The purpose of this code would be to promote cooperation and keep tensions low.

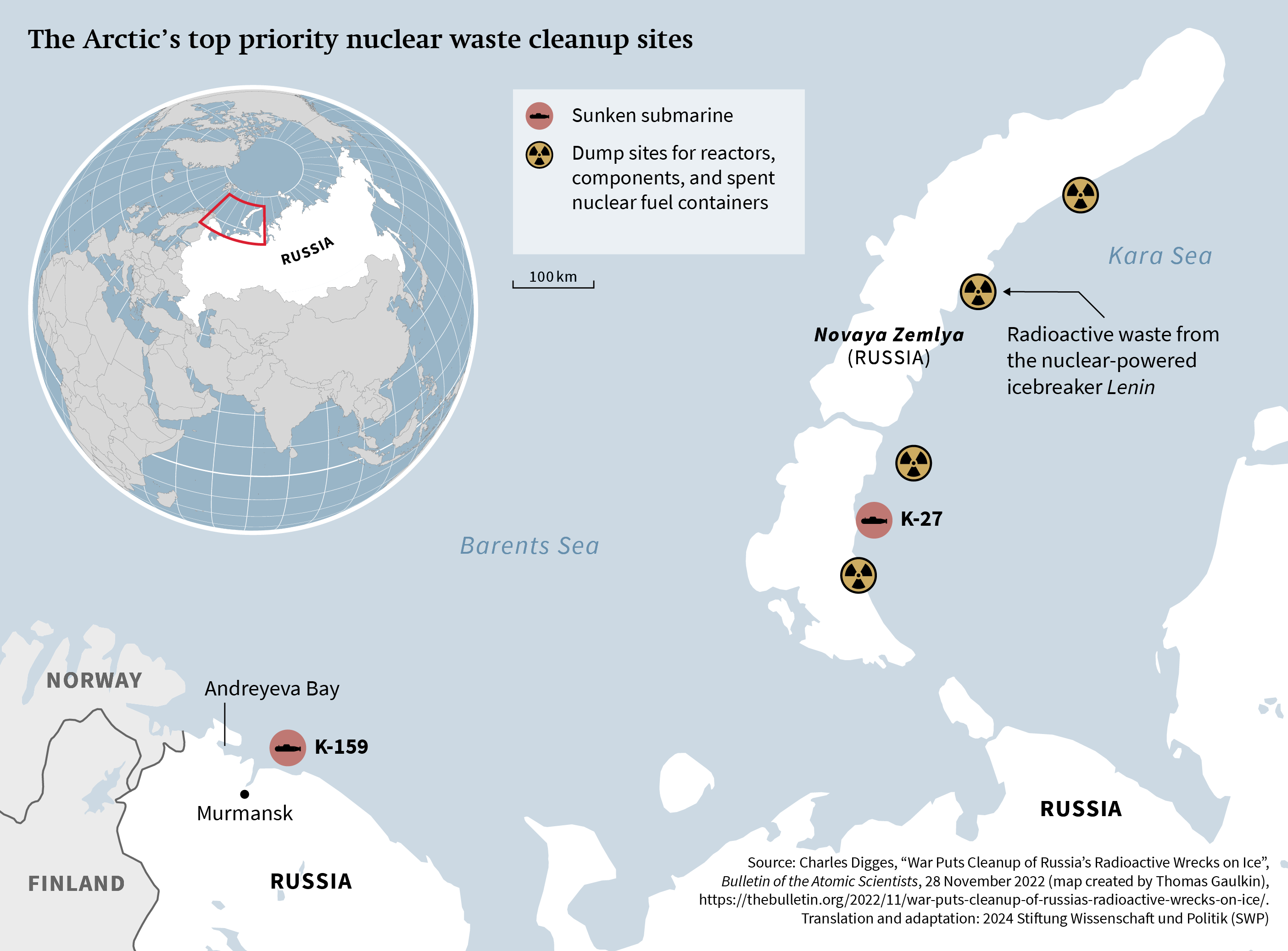

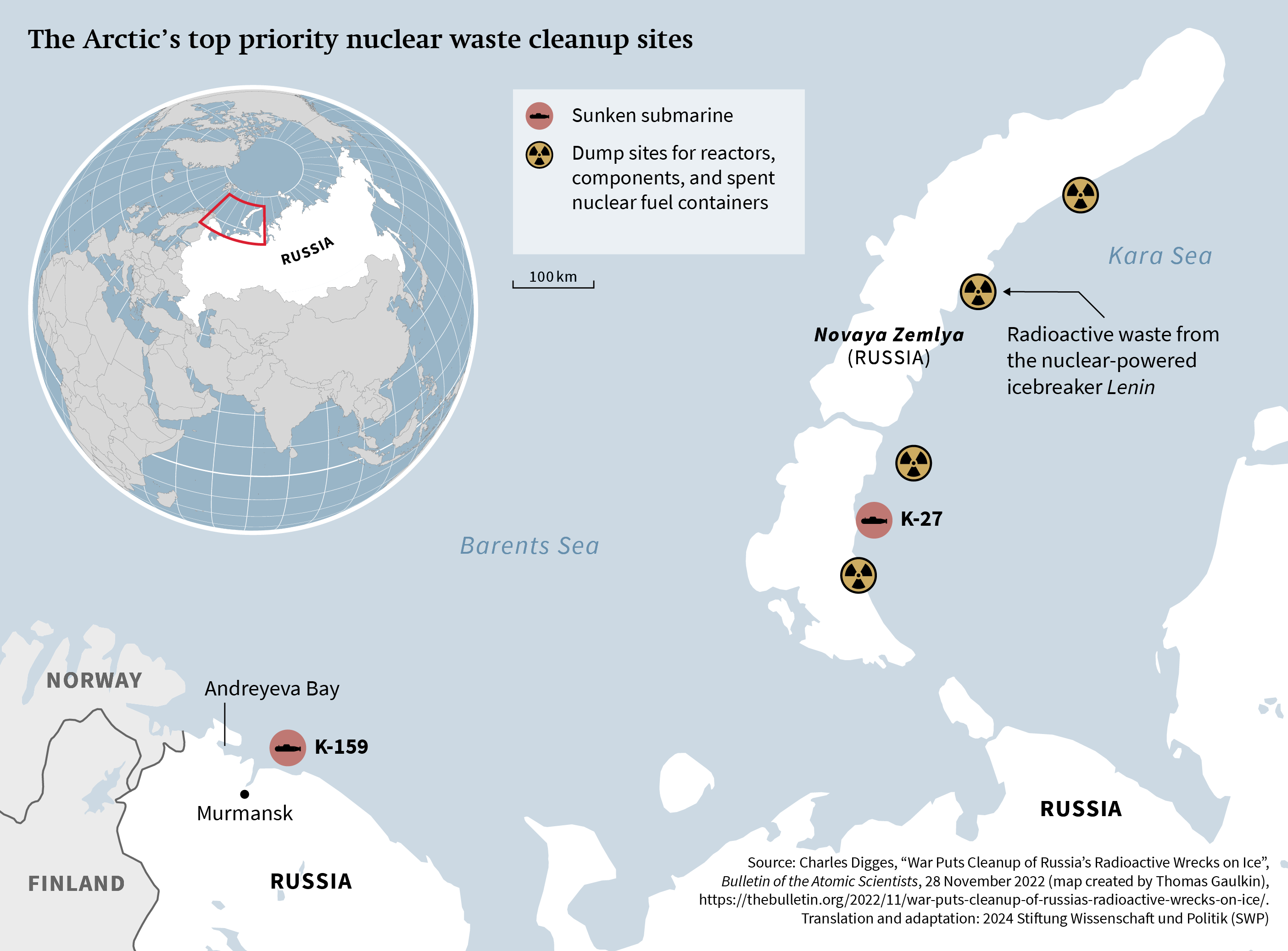

A resumption of cooperation in the nuclear realm would surely address spectres of the Cold War – whether submarine wreckage, nuclear weapons systems, reactors, or fuel rod disposal systems – which threaten to contaminate the fish-rich Barents Sea and adjacent areas – as far south as Norway – with radioactive material in the long term. This is one reason why Oslo has taken the lead in cleaning up Russian wreckage and waste in the High North in the past. A proposal put forward during the beginning of Russia’s chairmanship of the Arctic Council envisaged the recovery of two nuclear submarines (K‑27 in the Kara Sea and K‑159 in the Barents Sea) with financial support from the EU. The submarines would otherwise continue to corrode and eventually release radioactive waste. Beyond this, respective Russian and American researchers have submitted proposals on how to regulate the handling of civilian nuclear energy in the Arctic; both are follow-ons from the Arctic Military Environmental Cooperation that was founded in 1996. This cooperative efforts was aimed at mitigating the dangers posed by radioactive vestiges of Russia’s Northern Fleet, and it indirectly contributed to the establishment of what is today the Arctic Council.

Map

Source: Charles Digges, “War Puts Cleanup of Russia’s Radioactive Wrecks on Ice”, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 28 November 2022 (map created by Thomas Gaulkin), https://thebulletin.org/2022/11/war-puts-cleanup-of-russias-radioactive-wrecks-on-ice/.

Seeing that discarded radioactive material is a cross-border, transnational problem, there should be just as much interest in its clean-up in Moscow as there is in Oslo and other northern European capitals. Seeing that the prevention and clean-up of oil spills and search and rescue operations represent issues whose importance is undisputed among Arctic states and which has formed an essential basis for successful cooperation in the Arctic, the proper disposal and clean-up of radioactive material could come to constitute a similar realm of cooperation.

Berlin in the High North

The Arctic is a challenge for Berlin because security must be ensured on NATO’s northern flank, and even more acutely in the future. New arms control ideas require first and foremost the restoration of deterrence and defence capabilities. Deterrence only works if backed by substantial defence capabilities in the event that deterrence fails. The military potentials of both China and Russia, which have been growing for decades, must be taken into account in terms of their significance for the Arctic and North Atlantic region when it comes to determining adequate contributions to alliance defence. Only on the basis of such a shared perspective within NATO can promising arms control activities be determined. Similar to the NATO Dual-Track Decision initiated by Chancellor Helmut Schmidt in 1977, armament and arms control must both be considered as equally important, and a comprehensive rearmament process must be planned, financed and, implemented.

Even if Russia’s interest in stability in the Arctic grows, its war in Ukraine and ongoing confrontation with other Arctic states still serve to stabilise Putin’s regime. It therefore remains to be seen whether the Kremlin is prepared to take concrete actions to stabilise the situation in the spirit of arms control and thus to relativise the image of adversity that is useful to Putin, or whether it intends to expand the war given its already mobilised war economy.

For NATO’s navies, comprehensive maritime situational awareness is required in order to better detect and track Russian activities over, on, and under the water. It should be noted that cooperation between China’s Coast Guard and Russia’s Border Guard will increase as codified in the Murmansk Agreement of April 2023. The UK foresees an increase in the number of NATO’s P-8 maritime patrol aircraft alongside a proposal to extend cooperation between the US, UK, and Norway which should also involve countries such as Denmark and Germany.

Furthermore, the German Navy’s 2035+ objectives must be implemented as soon as possible. New F‑126 frigates should not only be suitable for operations in the sea ice of the Baltic Sea, but F-127 frigates should also be capable of operating in Arctic waters like the U212 CD German-Norwegian submarines. Long-range airborne surveillance and reconnaissance drones should also be equipped to operate in this arena, as should unmanned long-range underwater vehicles that monitor critical maritime infrastructure on the seabed.

Germany indeed needs to take a “new look” at the Arctic, and new guidelines for Germany’s Arctic policy will need to take shifting security considerations into account. It is rightly accepted that Russian aggression against Baltic states or in the Barents Sea would trigger a war with NATO. Nonetheless, because of Putin’s erratic behaviour, an escalation in the Arctic cannot be ruled out.

The restoration of trust is nowhere on the horizon, but in the meantime, a certain degree of cooperation on critical issues must continue where necessary during Russia’s war against Ukraine and where possible after the war, especially in the Arctic. As in climate policy, what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. However, how Russia’s war of aggression ends will have a profound effect on whether and how cooperation with Russia may occur in the future.

Dr Michael Paul is a Senior Fellow in the International Security Research Division at SWP.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2024

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2024C18

(Updated and expanded English version of

SWP-Aktuell 3/2024)

PDF | 318 KB

EPUB | 1.2 MB

MOBI | 2.9 MB

Russia’s war against Ukraine seems to have no immediate end in sight, the strategic competition between China and the US continues, and the expanding military cooperation between China and Russia increases the challenges facing the international community. In this context, the Arctic seems to be a relic of the past, no longer the “zone of peace” that Mikhail Gorbachev described in 1987. Indeed, this Arctic exceptionalism ended long before Russia’s war of aggression began. In order to restore at least a minimum level of cooperation, informal talks are needed that could help to provide perspective after the end of the war. Two former relatively uncontroversial projects could serve as starting points: the recovery of radioactive remnants of the Cold War and an agreement to prevent unintentional escalation, namely, another Incidents at Sea Agreement (INCSEA). A return to old approaches to arms control could pave the way to renewed cooperation in the Arctic in the future.

Generalised mistrust has supplanted the trust that once anchored the Arctic Council, and it is difficult to see at what level and by what means the forum can be brought back to constructive engagement. Under President Vladimir Putin, Russia has now either violated or terminated all remaining arms control agreements and fora. Trusting cooperation with Putin is no longer possible, and his aggressive, neo-imperialist policy will have a lasting impact. Yet, Russia still laments the loss of trust – as cynical as this may sound in view of the ongoing brutality of Russian warfare and violations of international law.

Reinstatement of the Arctic as an area of cooperation and stability is the long-term goal of all member states of the Arctic Council. Indigenous peoples and observer states, including Germany, are also likely to agree on this. Even Moscow seems to be interested in some kind of stability, particularly to enable the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation (AZRF) to function as its national resource base funded by foreign investments and thus to reduce its growing dependence on China. However, Russia currently remains on a collision course with the West. The hostilities in Ukraine will not end in 2024, which will be a decisive year in many respects; a historic NATO summit will take place in Washington and several elections will occur, including the US presidential elections in November.

In order to make future cooperation possible, it is advisable to reflect critically on certain measures that appear suitable to restore trust in the intentions and goals of Arctic actors. To this end, the original objectives and instruments of arms control should be reconsidered, and thought should be given to how they can be applied within the new Arctic security environment. This applies across the entire spectrum, from confidence-building measures to arms control of weapons systems.

The Arctic: a hotspot of climate change and an area of political opportunity

The Arctic is a good starting point for unofficial talks and an eventual resumption of positive diplomatic exchange, not least because of its geographic location far from current geopolitical hotspots in the Sino-American rivalry and its increasing importance for both China and the United States. According to Canadian political scientist Rob Huebert, the US, China, and Russia form “a new Arctic strategic triangle” which essentially determines the potential for conflict in the Arctic.

The effects of climate change in combination with strategic competition form a toxic mix when it comes to cooperation among the Arctic players. Due to continued warming, an ice-free Arctic Ocean will likely become a reality in the near future. In this case, the Arctic Ocean is expected to be covered by less than 15 percent sea ice in the summer months. Such a scenario is now foreseen to occur by the mid-2030s, whereas some time ago this was not expected until the middle or end of the century. Due to this development, sea routes and resources in the Arctic will be more accessible soon. Civilian and military activities are already growing and competition for access and influence in the Arctic is intensifying. This has created a need for rules governing states’ behaviour, while also taking into account transnational and indigenous relationships.

The increase of military activity requires arms control in the original and comprehensive sense. This means that potential adversaries should engage in all forms of military cooperation in the interest of reducing the probability, scale, and violence of a potential military conflict, as well as the political and economic costs of preparing for one. In this context, it is now a question of what can be used in the medium term to overcome the ongoing tensions and to shape mutually beneficial cooperation in the Arctic in the future. A certain degree of cooperation with Russia is necessary in order to avoid misunderstandings, miscalculations, and mutually undesirable events which could occur in the context of military activities. In the long term, stability is a prerequisite to the sustainable use of Arctic sea routes and resources. The Arctic states will need to involve new players such as China if a “peaceful, stable, prosperous and cooperative Arctic” is to be possible in line with the US Arctic strategy.

Such a constructive approach currently has little chance of success within Russia, as with many NATO states. The Kremlin sees the collective West as an opponent and perceives willingness to negotiate as a weakness. Within NATO, the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine has strengthened internal cohesion, but the alliance is not united on the question of how security should be guaranteed against Russia in the future. The opinion in many NATO states is that Russia can only be countered from a position of strength, which thus requires comprehensive rearmament. Others, on the other hand, also consider risk reduction measures to be reasonable, which would require a minimum level of cooperation. A clear decision on NATO’s political direction is not expected before this year’s summit in Washington and the US presidential election.

First and foremost, it is necessary to reach a common understanding of how future relations with Russia should be shaped after the end of the war against Ukraine. The Arctic is of central importance to Russia not only as a national resource base and sea route, but also as a zone of security that guarantees Russia’s maritime nuclear second-strike capability. For their part, the northern European states, as well as the US and Canada, are facing new types of military threats that require novel concepts and costly investment in capacities. Former concepts such as crisis stability are being challenged by the emergence of hypersonic weapons systems, and this puts political decision-making processes under even more pressure.

The security dilemma in the Arctic should be defused, the build-up of military capabilities contained, and crisis and conflict prevention measures should be introduced. Ideally, these goals can serve as building blocks for a future security architecture. Otherwise, the increasing activities in the Arctic – from civilian shipping to large-scale military exercises – exacerbate the risk of unintentional escalation as a result of misunderstanding or misperception. Thus, a dialogue on military security issues in the Arctic must be established.

At which level could the Arctic states resume dialogue?

Despite tensions with Russia, communication between the Arctic states continues, both at an official level, such as within the framework of the United Nations, and bilaterally insofar as it is enshrined in agreements that regulate border traffic, protect fishing activities, and maintain search and rescue commitments. Multilateral formats are also still active, for example among parties to the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement (CAOFA).

However, a security dialogue that includes Moscow and focuses explicitly on the Arctic no longer exists. Since its annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia is no longer involved in dialogue among the Arctic states’ military commanders (the Arctic Chiefs of Defence [ACHOD]) or in the annual meetings of the Arctic Security Forces Roundtable (ASFR). Germany, France, the UK, and the Netherlands are also represented at the ASFR. Other formats of which Russia is a member such as the Arctic Council and the Arctic Coast Guard Forum (ACGF) do not address military security, nor does the Barents Euro-Arctic Council, from which Russia withdrew in September 2023. Even before the war, experts widely agreed that Russia needed to be reincluded in dialogue, but opinions differ among politicians and experts as to how this should be done.

The most obvious solution seems to be the least realistic, namely extending the mandate of the Arctic Council to include military affairs. Indeed, the Arctic Council has a high degree of institutionalisation and has been successfully active for over two decades. The extension of its mandate would therefore appear to be easier than creating an entirely new format as it also already brings together all of the main regional players. In spite of this, member states would need to agree on broadening the Council’s mandate to include military security issues, and this has already been rejected by some members. While Iceland’s Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir and Finland’s Prime Minister Antti Rinne spoke out in favour of such a solution in the past, others voiced concerns that this could hinder cooperation. Former Norwegian Arctic envoy Bård Ivar Svendsen, for example, noted at a time of extensive cooperation that the dialogue with Russia in the Council only remained active precisely because security policy was not being discussed. Moreover, in 2021, Alaska’s Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) President Jimmy Stotts refused to address defence issues, stating, “[w]e don’t wish to see our world overrun with other peoples’ problems”. Consensus on this front therefore remains unlikely.

Another approach would be to resort to already established formats. For instance, in the beginning of Russia’s chairmanship of the Arctic Council (2021-23), Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov sought to reactivate dialogue between the general staffs of the Arctic states. With this in mind, Russia’s Arctic ambassador Nicolay Korchunov declared his intention to resume informal exchanges between military experts from the Arctic states. The war against Ukraine has put an end to these ideas, and the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO shows the need for an alternative interim approach aside from formats such as the ACHOD and ASFR that exclude Russia.

Even if scepticism is warranted, dialogue with Russia at an informal, expert level (Track 2) seems reasonable. This would make it possible to test potential approaches to confidence-building measures and, building on this, to initiate official talks at a formal level (Track 1) in due course. Informal talks are an instrument that stimulates reflective dialogue between actors in conflict, especially when discussions at official levels are difficult or even impossible. In today’s new mistrustful and competitive reality, it is important to restore a minimum level of stability. Dialogue between military experts from all eight Arctic states could constitute a new interim format and initiate a process in which confidence-building measures are developed.

To this end, the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) has had experience organising Track 2 (informal) and Track 1.5 (with officials) meetings with Russian representatives before the invasion of Ukraine. Russia has a very limited pool of experts who have little or no exchange with or influence over Russian policy- and decision-making. Since the beginning of the war, the Russian expert community has split into several groups: The first group has fled the country in exile; the second group is still in Russia, but is isolated and trying to fly under the radar; the third group is making a career for themselves by adopting or echoing the Kremlin’s rhetoric. Even if exchange with the second group could be constructive, these (former) experts would be putting themselves at extreme risk by engaging. Interrogations at the borders are commonplace and these experts can easily be declared foreign agents. Track 2 activities are also known to have been infiltrated by Russian intelligence services; and even in cases in which Moscow has authorised such talks (such as the 1993–2013 Armed Forces Dialogue seminars with Russia, organised by SWP in cooperation with the German Federal Ministry of Defence), no significant breakthroughs have truly been witnessed.

With this in mind, informal talks on arms control and transparency measures represent another possible realm of engagement that does not necessarily require mutual trust in order to be successful. Rather, such measures are a means of enabling predictable behaviour among parties who distrust one another and of creating trust in the long-term.

What kind of measures can restore trust?

Trust always involves a degree of uncertainty and the possibility of disappointment. Nevertheless, it also opens up more possibilities for action because, as the sociologist Niklas Luhmann puts it, “trust provides a more effective form of reducing complexity”. Those who act with confidence are optimistic about the future, which always contains a multitude of certain and uncertain events. If calculated rationally, risks cannot be eliminated, but they can be reduced. According to Luhmann, such points of reference can thus serve as a “stepping stone for jumping into a limited and structured uncertainty”.

According to its National Security Strategy, the German government “supports strategic risk reduction and the fostering of predictability, as well as the maintenance of reliable political and military channels of communication in relations between NATO and Russia. [It] remain[s] open to reciprocal transparency measures where the prerequisites for them exist”. This includes the development of new approaches based on behavioural arms control that can help reduce tensions.

In 2023, Russia’s Arctic ambassador Nicolay Korchunov once again expressed the desire for comprehensive cooperation that included military issues, stating that “[i]t can all be sorted out by dialogue, which would strengthen trust”. Despite this sentiment, it will be difficult to start a dialogue in view of the consequences of the war in Ukraine. Russia’s current policy gives little hope for constructive talks, as deliberately playing with unpredictability is one of Russia’s manipulation tactics to destabilise Western societies and institutions. This, however, should not prevent preparations and considerations with respect to how security and stability can be enhanced in the future.

Confidence-building measures (CBMs) should define acceptable and legitimate behaviour. They should help to promote transparency and reduce the risk of misjudgements, and hence, unwanted escalation. In this way, a certain degree of crisis stability and trust in the intentions of the other side can be fostered. This could mitigate the current security dilemma.

CBMs could, for example, focus on creating transparency with regard to military activities, and they could incorporate recommendations from the former NATO-Russia expert dialogue. For instance, Arctic military bases could be subject to mutual visits. A regular regiment on visitation could be established and plans for military exercises could be disclosed. Advance notice of Russian exercises could help to avoid misinterpretation. In turn, NATO allies could inform Russia about unscheduled activities.

Confidence- and security-building measures (CSBMs) are rooted in the Vienna Document on CSBMs. In the 1990s, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) created the world’s most advanced set of rules for arms control, verification, and CBMs. Now many of the agreements under this arrangement have either been suspended or weakened as partners withdraw. According to OSCE Secretary General Helga Maria Schmid, however, this does not mean that CSBMs will not play an important role again in the future, as the instruments are still available.

New dialogue requires constructive substance in the form of suitable projects that foster cooperation. In the long term, it is important to develop a new set of (multilateral) rules that serve both sides’ interests. According to a team of authors from the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt, two basic conditions must be met to facilitate an effective multilateral agreement: The rules must be designed so that they are appropriate for solving the problems and these rules must be adhered to by the involved states. Accordingly, the crucial question is to what extent these rules will restrict state action, including military action.

Potential cooperation projects

The oldest CSBM to prevent unintentional escalation is the Incidents at Sea Agreement (INCSEA), concluded between the US and the Soviet Union in 1972. Individual NATO states such as Norway have continued similar agreements with Russia, taking into account new technological developments. All contain similar provisions that can be qualified as CSBMs. While bilateral INCSEA agreements between states with naval forces operating worldwide make sense, a multilateral Arctic INCSEA agreement or a NATO-Russia INCSEA agreement that would apply to all naval ships in the Arctic Ocean would be more purposeful. In practice, it would be easier for navy officers to work with a single set of signals than with many different ones, as noted by a RAND study. This would also mirror considerations for a similar agreement between the US and China in the Western Pacific.

Further rules of conduct, such as a Arctic Military Code of Conduct, have long been discussed. One possible model is the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement, which provides a format for negotiations between the Arctic’s coastal states, four countries engaging in fishing activities in the Arctic, and the EU. In addition to the Arctic states, a military code of conduct could also include countries that are capable of military operations in the Arctic. The purpose of this code would be to promote cooperation and keep tensions low.

A resumption of cooperation in the nuclear realm would surely address spectres of the Cold War – whether submarine wreckage, nuclear weapons systems, reactors, or fuel rod disposal systems – which threaten to contaminate the fish-rich Barents Sea and adjacent areas – as far south as Norway – with radioactive material in the long term. This is one reason why Oslo has taken the lead in cleaning up Russian wreckage and waste in the High North in the past. A proposal put forward during the beginning of Russia’s chairmanship of the Arctic Council envisaged the recovery of two nuclear submarines (K‑27 in the Kara Sea and K‑159 in the Barents Sea) with financial support from the EU. The submarines would otherwise continue to corrode and eventually release radioactive waste. Beyond this, respective Russian and American researchers have submitted proposals on how to regulate the handling of civilian nuclear energy in the Arctic; both are follow-ons from the Arctic Military Environmental Cooperation that was founded in 1996. This cooperative efforts was aimed at mitigating the dangers posed by radioactive vestiges of Russia’s Northern Fleet, and it indirectly contributed to the establishment of what is today the Arctic Council.

Map

Source: Charles Digges, “War Puts Cleanup of Russia’s Radioactive Wrecks on Ice”, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 28 November 2022 (map created by Thomas Gaulkin), https://thebulletin.org/2022/11/war-puts-cleanup-of-russias-radioactive-wrecks-on-ice/.

Seeing that discarded radioactive material is a cross-border, transnational problem, there should be just as much interest in its clean-up in Moscow as there is in Oslo and other northern European capitals. Seeing that the prevention and clean-up of oil spills and search and rescue operations represent issues whose importance is undisputed among Arctic states and which has formed an essential basis for successful cooperation in the Arctic, the proper disposal and clean-up of radioactive material could come to constitute a similar realm of cooperation.

Berlin in the High North

The Arctic is a challenge for Berlin because security must be ensured on NATO’s northern flank, and even more acutely in the future. New arms control ideas require first and foremost the restoration of deterrence and defence capabilities. Deterrence only works if backed by substantial defence capabilities in the event that deterrence fails. The military potentials of both China and Russia, which have been growing for decades, must be taken into account in terms of their significance for the Arctic and North Atlantic region when it comes to determining adequate contributions to alliance defence. Only on the basis of such a shared perspective within NATO can promising arms control activities be determined. Similar to the NATO Dual-Track Decision initiated by Chancellor Helmut Schmidt in 1977, armament and arms control must both be considered as equally important, and a comprehensive rearmament process must be planned, financed and, implemented.

Even if Russia’s interest in stability in the Arctic grows, its war in Ukraine and ongoing confrontation with other Arctic states still serve to stabilise Putin’s regime. It therefore remains to be seen whether the Kremlin is prepared to take concrete actions to stabilise the situation in the spirit of arms control and thus to relativise the image of adversity that is useful to Putin, or whether it intends to expand the war given its already mobilised war economy.

For NATO’s navies, comprehensive maritime situational awareness is required in order to better detect and track Russian activities over, on, and under the water. It should be noted that cooperation between China’s Coast Guard and Russia’s Border Guard will increase as codified in the Murmansk Agreement of April 2023. The UK foresees an increase in the number of NATO’s P-8 maritime patrol aircraft alongside a proposal to extend cooperation between the US, UK, and Norway which should also involve countries such as Denmark and Germany.

Furthermore, the German Navy’s 2035+ objectives must be implemented as soon as possible. New F‑126 frigates should not only be suitable for operations in the sea ice of the Baltic Sea, but F-127 frigates should also be capable of operating in Arctic waters like the U212 CD German-Norwegian submarines. Long-range airborne surveillance and reconnaissance drones should also be equipped to operate in this arena, as should unmanned long-range underwater vehicles that monitor critical maritime infrastructure on the seabed.

Germany indeed needs to take a “new look” at the Arctic, and new guidelines for Germany’s Arctic policy will need to take shifting security considerations into account. It is rightly accepted that Russian aggression against Baltic states or in the Barents Sea would trigger a war with NATO. Nonetheless, because of Putin’s erratic behaviour, an escalation in the Arctic cannot be ruled out.

The restoration of trust is nowhere on the horizon, but in the meantime, a certain degree of cooperation on critical issues must continue where necessary during Russia’s war against Ukraine and where possible after the war, especially in the Arctic. As in climate policy, what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. However, how Russia’s war of aggression ends will have a profound effect on whether and how cooperation with Russia may occur in the future.

Dr Michael Paul is a Senior Fellow in the International Security Research Division at SWP.

© Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2024

All rights reserved

This Comment reflects the author’s views.

SWP Comments are subject to internal peer review, fact-checking and copy-editing. For further information on our quality control procedures, please visit the SWP website: https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/about-swp/ quality-management-for-swp-publications/

SWP

Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik

German Institute for International and Security Affairs

Ludwigkirchplatz 3–4

10719 Berlin

Telephone +49 30 880 07-0

Fax +49 30 880 07-100

www.swp-berlin.org

swp@swp-berlin.org

ISSN (Print) 1861-1761

ISSN (Online) 2747-5107

DOI: 10.18449/2024C18

(Updated and expanded English version of

SWP-Aktuell 3/2024)