Caravaggio/Andy Warhol/Keith Haring: Three Cases of Radical Innovation

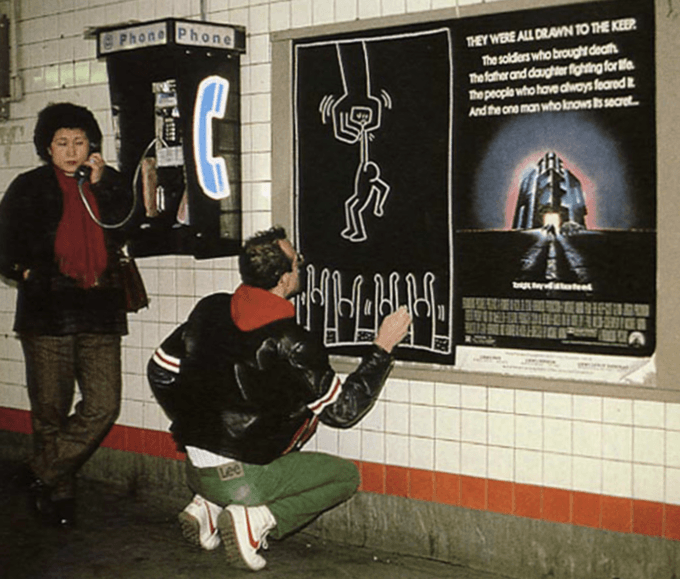

Keith Haring drawing in the New York subway. Image Singulart.

Sometimes development in the history of art involves a break with tradition. Consider three examples. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610) inaugurated his career by painting naturalistic genre scenes. Andy Warhol (1928-1987) started out as a commercial illustrator. And Keith Haring (1959-1990) first become known for making graffiti in the New York subway. They all created new works which were so radical-looking that they were often said not to be art at all. In a creative exercise of deskilling, these artists renounced the accepted ways of understanding art making, in favor of novel conceptions of a painter’s skill. At the time, their works looked all wrong to the connoisseurs. Caravaggio’s figures looked too naturalistic to be artworks, Warhol’s illustrations images of subjects too banal to be acceptable, and Haring’s drawings too simplified to be interesting. Responding to such radical originality can take time.

The Yale art historian George Kubler developed a conceptual tool which is useful here, the entry point. How an artist can develop depends upon the resources available in her or his visual culture. The very diverse achievements of Caravaggio, Warhol and Haring depended upon their very distinctive entry points. And so, to understand their art we need understand the options available within their art worlds. Caravaggio arrived in Rome when there was an established market for small genre paintings, and a place for novel ambitious sacred works. Warhol got to New York when, Abstract Expressionism has created a strong market for contemporary American art. But that movement was spent and so it was time for something new. And Haring arrived there when life down-and-out in downtown Manhattan was very cheap, art school education was affordable and there was an newly developed international market for novel American artworks. Caravaggio’s Rome, like Warhol’s and Haring’s New York was a great place to study recent developments. These entry points created an opening for their radical innovations.

In all three cases there was clearly such an obvious art world destination for an ambitious artist, Rome in 1600 and New York in the mid and late twentieth century. Had Caravaggio remained in Milan, Warhol in Pittsburgh (where he was born), or Haring in Pittsburgh (where he first went to art school), then they would have become at best successful provincial artists. That’s what defines an art world center, which is a place where ambition may be rewarded. Had anyone with their particular skills arrived in the centers of the art world a couple of decades earlier, it is hard to know what they could have made of the situation, for the art world was not yet ready for them. And a couple of decades later, it would have been too late. Needless to say, identifying the character of these entry points is only to pick out the necessary conditions for serious achievement.

In retrospect, the achievement of radically innovative artists can be understood historically. There were precedents for Caravaggio’s naturalism, Warhol’s pop subjects and Haring’s line. And when we do that, then continuity is restored to our history of art. What, however, can be harder to see is what happened right when radically original work appeared. Consider the case of Haring. There was a great deal of graffiti on 1980s subway cars. But he seems to have been the one artist who saw the potential of the blank panels, which waited to be covered by commercial advertising. There was a vast audience for drawing on these sites. And, of course, he had the skill needed to work very quickly, which was necessary because doing this public art making was illegal.

Once their early work attracted attention, these three men entered the art world by upscaling their work. Caravaggio moved from genre painting to sacred narratives; Warhol went onward to making Pop Art; and Haring began doing murals. They thus discovered that their basic skills were adaptable to these novel situations. And so Caravaggio did radically original altarpieces; Warhol a variety of subjects borrowed from mass media; and Haring public street art. There were a lot of ambitious painters in Rome, circa 1600 and in Manhattan in the 1950s. And many gifted young people doing graffiti in New York in the 1980s. But, so far as we can see, none of these contemporaries of Caravaggio, Warhol or Haring had their skills of adaptation. Looking just at Caravaggio’s early genre paintings, Warhol’s commercial work in the 1950s, or Haring’s subway drawings circa 1982, it would not have been easy to predict their later accomplishments.

In a classic essay “Other Criteria,” originally presented in 1968, Leo Steinberg argued that the birth of post-modernism, the tradition coming after modernism, required new evaluative criteria. His analysis is highly relevant here, for the same is true, in a more dramatic way, of the painting of Caravaggio, Warhol and Haring. Initially their art was very hard to understand because it broke with accepted standards. In crowded art worlds, the ability to swiftly innovate gets well rewarded, for it allows an artist to stand out. And so it’s the essential task of the art critic to also respond quickly, and prepare the public to understand what is happening. These three men worked in very different situations. And so it’s surprising to see the deep analogies in their situations.

No comments:

Post a Comment