A general strike in Belarus could bring the Lukashenko regime down, but so far it has failed to reach critical mass

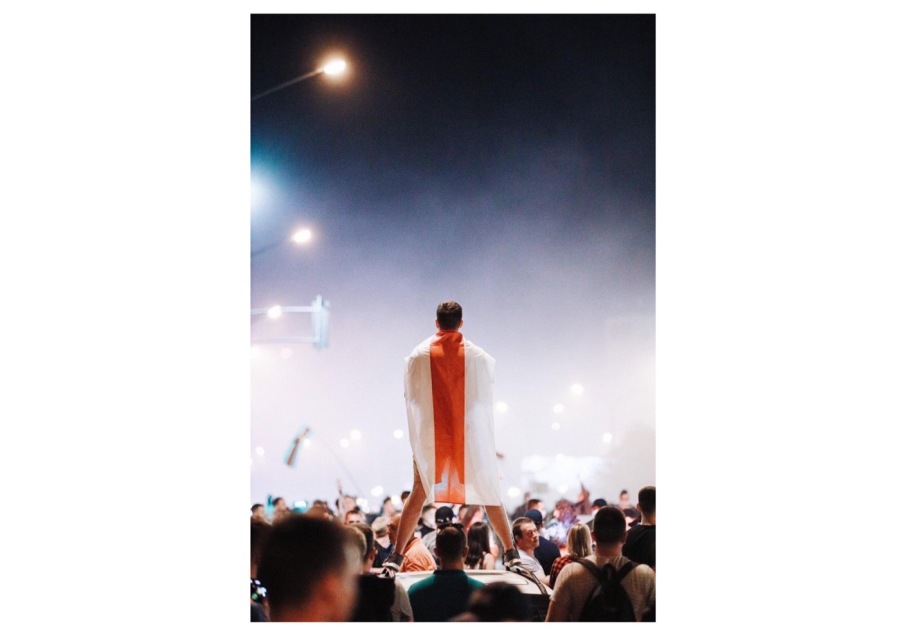

The mass rallies that have filled the streets of Minsk for the last three weeks are inspiring, but it is the general strike by the blue collar workers, traditionally Belarus' self-appointed President Alexander Lukashenko’s core supporters, that could bring his regime down.

The extent of the population’s disapproval only really became apparent when workers at the biggest state-owned enterprises rebelled during the first week of protests and chanted “get out” to Lukashenko’s face when he was foolish enough to address the employees at the MZKT truck factory on August 17, supposedly a bastion of support. It was dubbed his “Ceausescu moment” by pundits and he quickly left, looking visibly shaken by the experience.

But the general strike took a little time to take hold and experts say that it has failed to reach the critical mass needed to force Lukashenko from office. The first call for a general strike was made by the Telegram channel Nexta, which has become the de facto organiser of the protest movement, on August 11. It flopped.

A few workers downed tools, but were quickly arrested by waiting security services agents and disappeared into the detention centres that consumed 6,600 protestors over the first three days of general protests, who were horrifically beaten, raped and tortured.

But it was that very ill treatment that gave the general strike the impetus it needed. As details of the beatings emerged the entire population – including the factory workers – were radicalised. On August 13 the workers of state-owned company after state-owned company walked off the shop floor and the general strike became real.

Taking a leaf out of the Polish Solidarity movement that brought Polish industry to halt in the '80s, paving the way for the collapse of Soviet control and which celebrated its 40th anniversary this year, most of Belarus’ biggest companies have been affected. Bring the economy to a standstill is one of the most powerful weapons the population have to force Belarus' Lukashenko to the negotiating table.

However, despite the popular outrage the strikes are partial at most plants as many workers remain intimidated by the threat of the sack and Lukashenko’s promise to lock them out of any future employment if they do down tools.

And Lukashenko is not going to give up without a fight. He has called for the dismissal of workers for participating in strikes. “We have surplus personnel at MTZ [Minsk Tractor plant], MAZ [Minsk Automotive Works], BelAZ [Belarus Automotive Works] – everywhere. Let them go! But after that there should be no place for them in factories,” Lukashenko said on August 15, adding that he would close all enterprises where a strike began. However, none of them have been closed yet.

He also threatened to replace the staff of state-owned plants with Ukrainian workers, in comments that immediately backfired. Having lived through two revolutions that ousted two presidents already, the head of a mining union in Ukraine quickly put out a statement that no Ukrainian workers would travel to Belarus and his union was with the Belarusian people.

But following Russian President Vladimir Putin's statement that he was willing to send a special military unit to quell the protests “if necessary” on August 27, Lukashenko has taken back the initiative and re-launched his campaign of intimidation in an effort to reassert his control.

It has been hard to assess how widespread the strikes have been and what impact they have had on Belarus’ leading enterprises. An investigation conducted by RBC estimated a total of 30 enterprises have been affected, although other estimates put the number at 150, which collectively have revenue equivalent to 27% of Belarusian GDP, based on last year’s results.

Of these state-owned enterprises (SOEs), every fifth is engaged in mechanical engineering, and every sixth is engaged in food production. The rest are involved in oil refining, transportation, fertiliser production, construction and electrical engineering, according to RBC.

The irony of the Belarus protest being an “old school” traditional revolution where it is the working classes that are holding their oppressors to account has not been lost on commentators.

“I love the idea that the working class can be the backbone of the current revolutionary movement in Belarus,” wrote Renaissance Capital chief economist Charlie Robertson on August 14 as cited by RBC, as the strikes were picking up steam.

But the state continues to up the ante and is already carrying out reprisals against workers who refuse to work. “The shutdown of enterprises is not only a decline in wages, loss of markets and the closure of production facilities, unemployment, a fall in the ruble and a rise in prices. Who and what will say to those who have lost their jobs when a budget clinic or school is closed near their home? One day a communal apartment will double in size, and no one will take out garbage from the yard for weeks,” warned the State Secretary of the Security Council of Belarus Andrei Ravkov, who has just been replaced as Lukashenko shores up his control over the security organs.

Part of the problem is while workers' unions have always been around, they were developed as another mechanism of control and were a throwback to Soviet-era unions that were designed to give the veneer of a “Workers' Paradise” rather than be truly representative bodies of the workers’ interests.

Workers have come out on strike as individuals, appalled at the mistreatment of the people by the police, rather than being taken out on strike by national level union organisations. As a result, the strikers are vulnerable to threats by the enterprise managers who remain loyal to the state and who are singling out the most vociferous strikers for punishment and dismissal. In other reported incidents workers have simply been locked in on shop floors and not allowed to leave the work place.

Another tactic employed by workers to avoid retribution but nevertheless cause the state problems is the “Italian strike”, where they go to their work places but basically do nothing. However, it appears this tactic too has failed to catch on and has not been effective.

According to IMF estimates, state-owned enterprises create more than 30% of added value in the country's economy, which is significantly higher than in other Eastern European countries; for comparison SOEs account for 10% of GDP and in Russia 15%, according to RBC. According to the National Statistical Committee of Belarus (Belstat), at the end of March 2020 the state owned 3,220 legal entities and employed 1.25mn people from a total population of just under 10mn, or 42.8% of the total working population.

RBC concludes that much of the strikes are actually protests and the strike movement has not gained a critical mass that would put the government under sufficient pressure to force it into negotiations. Moreover, as time passes the authorities' pushback is already effectively undermining the movement as the most militant workers are removed.

Belarus’s economy in danger of a crisis in the face of sustained popular protests, says IIF

Gripped by mass protests and a general strike, Belarus will struggle to meet its debt obligations this year and faces a serious economic crisis, reports the Institute of International Finance (IIF) in a paper released on September 2.

“Widespread protests, which began in the aftermath of the disputed presidential election on August 9, have now entered a fourth week, and the ultimate outcome of the stand-off remains uncertain,” Elina Ribakova, deputy chief economist with the Institute of International Finance (IIF) and economist Benjamin Hilgenstock said in a paper IIF shared with bne IntelliNews. “After some concessions in recent weeks, authorities have reverted to a tougher stance, likely emboldened by Russian promises of support to Lukashenko.”

The EU has threatened to impose sanctions on government officials but so far only the Baltic states have imposed any new measures – mostly personal travel bans and asset freezes targeting the individuals organising the torture and repression in Belarus.

US Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun met with opposition candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya this week but did not comment on whether similar steps were being considered by the US.

The international response to the events in Belarus has been loud condemnation, but very limited action, part at the request of the opposition themselves, who are wary of being dragged into the geopolitical stand-off between Russia and the West.

Funding the regime

Russia’s continued support is essential for Belarus, as it holds almost half of the country’s $17bn of public external debt (47%). In addition, Minsk is highly dependent on Russia’s energy subsidy, as well as exports to and imports from its eastern neighbour. About 40% of Belarus’ exports go to Russia, which also accounts for 40% of all the inbound investment. The true share of Russian inbound investment rises to more than half if the investment from Cyprus and the Netherlands is assumed to be Russian money too.

As bne IntelliNews reported, the Belarusian ruble (BYN) has already lost some 11% of its value against the dollar in the last month and the government only has about $8.9bn of reserves ($4bn in dollar cash and the rest in gold and assorted assets), or equivalent to 2.4 months worth of imports. Economist say that a country needs a minimum of three months of import cover equivalent to ensure the stability of the national currency.

“While the National Bank of the Republic of Belarus (NBRB) denied rumours of FX shortages as it tightened liquidity to prevent further pressure on the currency, external financing stress could reach precarious levels,” warn Ribakova and Hilgenstock.

“In our baseline scenario, which assumes a drawn-out political stalemate in the context of $2.3bn in upcoming public external debt service, reserve losses would reach $3bn in 2020 – almost 1/3 of Belarus’ total reserves of $8.9bn,” the economists add.

Year-to-date, the currency has weakened by 26%, according to IIF, reflecting not only political uncertainty but also disruptions as a result of the coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemic that has raged unchecked due to Belarus' self-appointed President Alexander Lukashenko's unwillingness to take it seriously.

“This follows a period of a broadly stable BYN/USD exchange rate over 2016-19. As FX shortages appear to mount, high dollarisation is limiting the NBRB’s ability to step in as lender of last resort. Further dollarisation, for example as a result of attempts to ‘buy-off’ striking state-owned enterprise (SOEs) employees through the printing of money, could put significant pressure on already-limited reserves,” Ribakova and Hilgenstock said.

While it appeared that Lukashenko could be swept out of office by the popular uprising that has engaged almost the entire population from the liberal middle class to the blue collar workers in the SOEs, Lukashenko traditional base, that all changed following Russian President Vladimir Putin statement that he was willing to send a special military unit to quell the protests “if necessary” on August 27. The result of this statement was to significantly bolster Lukashenko's position and will almost certainly lead to the standoff being protracted.

“In this scenario, the Lukashenko regime will reject demands for a peaceful and organised political transition, but also refrain from any major escalation of its response to ongoing demonstrations. As a result, Western countries will likely limit sanctions to specific individuals and entities directly responsible for acts of oppression and hold back with respect to measures targeting major SOEs,” said IIF.

With the current regime remaining in power, Russia is expected to roll over existing debt and provide additional funding, thereby alleviating external financing stress and allowing Belarus to avoid a financial crisis, according to IIF. “Nevertheless, pressure on Belarus’ already-low reserves would be significant, even if manageable over the near term,” IIF added.

IIF considered two additional scenarios: one that assumes a peaceful transition of power leading to an opening-up of the economy (upside scenario); and one that assumes a deterioration of the political conflict and eventual escalation of violence (downside scenario).

“In the former, Belarus would attract inflows from international financial institutions (IFIs) and bilateral partners in the West, while maintaining its strong relationship with Russia,” say Ribakova and Hilgenstock.

In the positive scenario higher non-resident inflows, together with lower resident outflows, would allow for reserve gains of $1.75bn in 2H20 (and $1bn for the full year), according to IIF estimates.

In the negative scenario sanctions would be extended to SOEs and IFI support becomes out of the question. As a result, resident capital flight would accelerate to $3.5bn and surpass the record of $2.6bn in 2011, when Belarus had its last crisis and deep devaluation.

“Not included in our scenarios are additional risks to the [current account], which could partially stem from the loss of IT service revenues (over $2bn in 2019),” Ribakova and Hilgenstock say.

The IT industry has been the main driver of the economy in recent years, and in addition to bringing in export revenues equivalent to a quarter of the country’s entire hard currency reserves it also continues to grow at over 30% a year, industry experts told bne IntelliNews in a recent podcast. However, both Japanese-owned Viber and Russian-owned Yandex have already closed their offices and an exodus of IT companies is anticipated after over 300 IT CEOs signed a letter warning they would leave the country if Lukashenko did not end the repression after the police crackdown began in the first week of protests.

The outlook for the Belarusian economy is now highly uncertain. Russia has stepped in with financial aid before in times of political or economic crises but used it to exert pressure on the Lukashenko regime. The same is likely to happen again now. Putin has invited Lukashenko to Moscow in the near future where the Union State deal, that was agreed in principle in 1999, could be signed into existence that will bring the two countries much closer together, creating an eastern version of the Eurozone, including a single currency.

“However, the scale and persistence of the current protests is unprecedented. In the absence of meaningful external pressure, with protesters undeterred and the regime’s ability to suppress the opposition largely remaining in place, we see no reason to expect an end to the prevailing political stalemate,” say Ribakova and Hilgenstock.