How one B.C. group, First Nations bought out trophy hunters

Buying out trophy hunters

Butchart Gardens, the slopes of Whistler, a wine-lover’s adventure through the Okanagan — these are some of the hot spots many tourists to British Columbia look to tick off on their way through YVR.

But for a select few, the province’s draw lies in its woods, broken highlands and rugged coastlines, a canvas to hook a 30-pound salmon or bag a huge diversity of big game.

“About 75 per cent of our clientele are international clients,” says Scott Ellis, CEO at the Guide Outfitters Association of British Columbia (GOABC), which represents between 60 to 70 per cent of the roughly 245 fishing and hunting outfitters in the province.

“We've got species of stone sheep and mountain goat you’ve got nowhere else. We’ve got three kinds of moose.”

As of 2017, GOABC says the industries brought in $192 million and employed about 2,500 people. When the pandemic hit, that business evaporated overnight, leaving fishing lodges and hunting guides to shut down or struggle on a trickle of dedicated hunters from places like Ontario.

According to government data, the 2020-21 season saw a more than a four-fold decline in the number of hunting licences issued to hunters from outside of B.C. In the biggest post-pandemic decline, the number of licences sold to non-residents to kill black bears fell 23-fold, dropping from 2,210 in the 2019-20 season to 96 last year.

Elsewhere across Canada, Dominic Dugre, president of the Canadian Federation of Outfitter Associations, says hunting guides have lost 99 per cent of their clients.

Desperate for a paycheque, many guides had moved into construction or the oil and gas industry. Business had climbed back up to 85 per cent in the fall and things looked up.

Then Omicron hit. Now many of the guides still operating are turning to offer their hunting cabins to clients more interested in snowshoeing, hiking or viewing wildlife, says Ellis.

“You don’t have any revenue for a year and a half, it’s pretty devastating for those folks,” he says.

For others, that pivot isn’t coming fast enough. The drop in foreign trophy hunters during the pandemic has offered a glimpse of a province where killing animals for sport is relegated to the past.

Most British Columbians agree. One 2015 survey found 91 per cent of B.C. residents opposed hunting animals for sport; another in 2017 found four in five Canadians supported an outright ban on trophy hunting.

In 2017, the province banned the grizzly trophy hunt, but left opponents questioning, what if another government overturns that decision?

A more pressing concern, say conservationists: the B.C. government has moved to defer old-growth logging, there remains no legal shield to protect roughly 60 species preferred by trophy hunters, such as black bears, wolverines, cougars and wolves.

Some B.C. First Nations run their own trophy hunting guide operations, while others, like the Coastal First Nations, argue that there is no good economic or ecological justification to kill animals for sport — a bear, they say, is worth far more alive than dead.

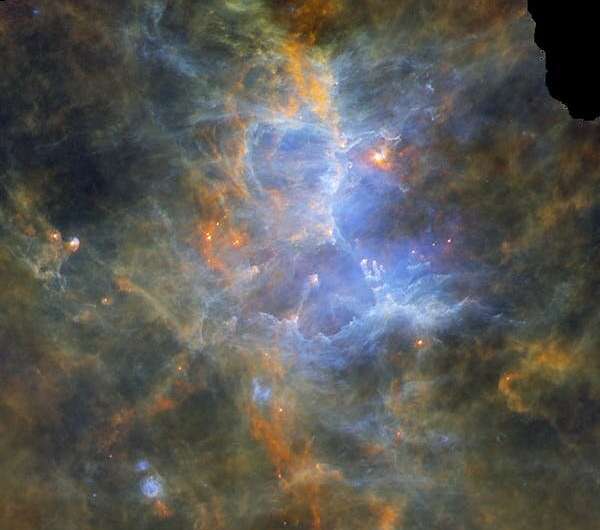

Over 500 kilometres from British Columbia’s biggest urban centres, where fjords butt up against the largest intact coastal temperate rainforest in the world, First Nations fought trophy hunters and won.

As B.C. looks to reset how it manages forests in the province, the victory against trophy hunting offers lessons for an alternative path: how to phase out an extractive industry and replace it with something that lasts. ?

BUYING THE RIGHT TO LIVE

One day over two decades ago, Brian Falconer remembers looking around and thinking, “I have nothing in common with these people.”

A former angling guide turned conservationist, in 2005, Falconer, along with other First Nations, began to have some “serious confrontations” with a guide outfitter who owned a trophy hunting tenure in the Great Bear Rainforest.

At the time, Falconer says there was “zero interest” in moving away from trophy hunting. The province charges less than $2,000 for a five-year commercial hunting guide licence. But the seemingly endless supply of rich foreign hunters willing to pay thousands of dollars for a single trip means the value of commercial hunting licences skyrocket.

Despite the financial incentive to hold on to the licences, hunting guides still had to put up with the people opposing them. “When are you going to leave us alone?” Falconer remembers the guide telling him.

At the time, Doug Neasloss, chief councillor of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais, had been working to build up an ecotourism industry in his community of Klemtu since the 1990s.

The First Nation’s 5,000 square kilometres of traditional territory extends deep into the Great Bear Rainforest, a place with a huge diversity of wildlife and the highest concentrations of spirit bears in the world.

The early years were bumpy. After the First Nation’s kayak guide business failed, Neasloss says they decided to focus on the bears.

People started coming from around the world to see them. But there was a problem. In the early 2000s, Neasloss says wildlife guides would keep running into gruesome signs of a trophy hunt: dead bears with no head, no fur and no paws, left to rot.

When they did see a live bear, Neasloss says they were so terrified of the hunters they would usually be running away into the bush.

That’s when Kitasoo/Xai’xais and Falconer’s organization, Raincoast Conservation Foundation, struck upon a solution. Why not buy out the hunting guides directly??

In 2005, the hunting outfitter agreed and Raincoast bought the commercial hunting rights to a 25,000-square-kilometre tract of land. Since then, they’ve purchased four more tenures, effectively ending trophy hunting in over 38,000 square kilometres of forest, an area larger than Vancouver Island.

Instead of bringing in hunters with long-barrel rifles to shoot bears, guides take visitors on boats, helicopters and into the forest wielding camera lenses and binoculars. Slowly, the animals learned to no longer fear the mere presence of humans, says Neasloss.

Evidence shows the strategy is paying off.

Since 2005, Falconer calculates more than 1,300 animals, including nearly 900 bears, have had their lives spared in the commercial hunting tenures they control. By 2030, the number of animals saved from a trophy hunt will soar to nearly 5,000, including second- and third-generation bears that would never be born were their parents killed.

“You’re literally buying the right not to kill these animals. You’re buying the lives of these animals to live every year,” says Falconer, who now works as Raincoast’s Guide Outfitter Coordinator.

REBUILDING A COMMUNITY

Long before he was chief, Neasloss was a guide. When he started in the 1990s, unemployment had soared to almost 90 per cent in Klemtu.

“There just wasn't a lot of opportunities here. We live on an island on the Central Coast, extremely isolated,” he says.

In a year Neasloss describes as “a dark time for our community,” Klemtu was devastated by a series of deaths. Suicide, he says, spread like a "contagious virus" taking many of the community's young people.

The community organized to make changes, but many were skeptical tourism would take them in a positive direction.

At one band meeting, people stood up and said they worried outsiders would come into the community, peering into people's windows, buying up all the food at the store and running the fuel station dry.

For a people who have bears embedded in their dance, stories, art and identity, the biggest question, says Neasloss, was “am I selling my culture?”

The community of Klemtu spent a lot of time deciding what was culturally appropriate to share with outsiders and what was off-limits.

In the decades since, Klemtu has seen significant change. One of its architectural showpieces, the Spirit Bear Lodge, is a modern take on a traditional longhouse overlooking the Great Bear Sea. From bedroom windows, visitors from around the world can spot humpback whales and otters before setting out to explore the First Nation’s territory.?

Tourist revenue started to double, growing from $100,000 annually to roughly $2.5 million in 2019. Jobs followed. The ecotourism operation has grown from a two-man operation to employing roughly 40 per cent of the community’s working population. Dozens more benefit from the outfit’s economic spin-offs, from the band store to boat operators and local artists.

Beyond a financial windfall, it’s given the people of Klemtu a chance to raise the next generation of stewards to look after their traditional territory and stay connected with their culture.

“They get paid to be themselves, they get paid to be Indigenous. They get paid to interpret who they are and where they're from, and share the culture with people from around the world,” says the chief.

A GROWING SOLUTION — WITH LIMITS

Beyond Klemtu, nine other Coastal First Nations — out of 204 total across B.C. — have entered into partnerships with Raincoast to manage their territories.

Falconer says his group can only buy out trophy hunting licences where there’s a willing buyer and he has support from First Nations. Ellis, meanwhile, says he supports any “willing seller, willing buyer” agreement.

First Nations’ roles are essential. Without them, there would be nobody to keep an eye on roaming trophy hunters, or regulate a permit system to limit the number of non-Indigenous tour guides operating in the territory.

“We don't want it to be overrun,” says Neasloss, whose nation offers 18 permits to sport fishing and ecotourism guides. “We don't want it to be like the Galapagos and we want to make sure it's sustainable.”

More than 400 kilometres down the coast at the southern end of the Great Bear Rainforest, the Homalco First Nation is the latest community to partner with the Raincoast Conservation Foundation.

Last month, the conservation group announced it was working to raise $1.92 million to purchase its sixth hunting tenure — this one at more than 18,000 square kilometres. If the sale goes through, First Nations and conservationists will have protected a piece of land bigger than the entire country of Costa Rica.

As Falconer put it at the time, “This is part of a just transition to a new economy.”

That “new economy” means Homalco tour operators have hosted a number of high-profile celebrities over the years, adding an even bigger draw for young people deciding what to do with their future.

“What the residential schools have done was the shaming around our culture and being First Nations,” says Homalco Chief Darren Blaney. “It takes that away and then it shows you there's people that value what our people knew — artisanal knowledge, how our people survived in the territory.”

With the rich and famous come big tips from such celebrities as Prince Edward, Microsoft's Bill Gates, and one of the guides' favourites, actor and comedian Chris Rock.

Studies carried out by Raincoast and First Nations have found an economy based on ecotourism generates 15 times more employment and 11 times more direct revenue than one based on trophy hunting. But relying on destination tourists also has its downside.

The flights, the lodging, the time — it all adds up, meaning many of those who can afford it are wealthy clients coming from Europe and Australia, or from the United States. A border closure that affects trophy hunters also affects wildlife guides in Klemtu and the Bute Inlet.

Guides haven't been idle. Kitasoo/Xai’xais operators have used the opportunity to help scientists determine how long a bear viewing group can stay and how big it can get before impacting the local ecosystem.

“A lot of that science is not out there in British Columbia, so we thought we'd take a lead on it and that gives us the information to be able to back up some of our management closures,” says Neasloss.

The two years downtime has also prompted Coastal First Nations, including the Kitasoo/Xai’xais, to remove hundreds of tonnes of trash in one of the largest beach cleanup operations in the province’s history.

And despite the pandemic, bear viewing tours are booked two years in advance with a full slate of visitors scheduled to arrive in Klemtu next spring. With the rise in Omicron cases, Neasloss says they still have another month before they have to start making decisions on delaying tours.

In the end, he says, “we’ll find ways to keep people employed.”?

'AN INCREMENTAL APPROACH'

Outside the pandemic, both communities are looking ahead to an even bigger transition, a carbon-neutral world. Klemtu already runs its own micro-hydropower generating station and a number of houses have been upgraded with heat pumps and solar panels.

But like any ecotourism operation relying on foreign visitors, mitigating emissions from international flights remains a big unanswered question. How do you build a business celebrating nature when clients are dumping thousands of litres of jet fuel emissions into the atmosphere to see you?

One solution is to turn to clients closer to home. While Neasloss and Blaney both say they’ve seen a growing number of Canadians join their tours, there’s still not a big enough pool of local people to replace international travellers.

For the Homalco, Blaney says removing trophy hunters from their territory needs to be seen for what it is — a cog in a system of government-regulated extractive industries that have long shut out First Nations.

In that light, partnering with Raincoast and working to build the high-end tourism infrastructure seen in Klemtu is part of what he calls “an incremental approach” to regain full control over its territory.

It's an understanding of a world where biodiversity loss and a warming global climate system cannot be separated. But neither can the people that keep watch over the land.

“We're gonna start saying ‘it’s our land,’” says Blaney. “You got to get ready for a new landlord.”