Norway Considers Opening Huge Area To Deep Sea Mining

Norway’s government plans to submit to Parliament in the coming weeks plans to open a large area to deep sea mining as it seeks to access and extract critical minerals from the seabed.

The government has prepared an impact assessment which was open for comments until the end of January this year. The Petroleum and Energy Ministry now plans to submit a report and a plan to open a Germany-size area to deep sea mining to Parliament, which is expected to vote on the proposal this autumn.

The plan has drawn opposition from environmental groups and the fishermen’s association.

The government and the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) believe that deep sea mining could become an important new industry in Norway and could help raise supply of metals key to the energy transition.

Deep sea mining could help Europe meet the “desperate need for more minerals, rare earth materials to make the transition happen,” Amund Vik, state secretary in Petroleum and Energy Ministry, told the Financial Times.

Early this year, the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate issued a resource assessment, in which it said that there were “substantial resources on the Norwegian shelf.”

Copper, zinc, manganese, cobalt, rare earth minerals, and other critical minerals could be found on the Norwegian seabed, according to the report, which noted that “The NPD’s assessment is that the resources in place are significant. For several of the metals, the mineral resources compare to many years of global consumption.”

Still, the NPD noted that “It remains to be seen whether the areas will be opened, and whether production can be profitable from a financial standpoint.”

At the end of the consultation period in January, Norway’s Fishermen’s Association said that the impact assessment had “significant shortcomings” on the impact on environment and fisheries. The government’s assessment “is not a good enough decision-making basis to authorize a possible opening of large parts of the Norwegian Sea for deep sea mining.”

WWF’s Norwegian chapter, Greenpeace, and other environmental organizations called on the government to halt the process of opening the shelf to deep sea mining as the assessment has many unanswered questions about the consequences of exploration and extraction on the Norwegian economy, climate, and seabed habitat.

By Tsvetana Paraskova for Oilprice.com

Norway proposes opening Germany-sized area of its continental shelf to deep-sea mining

Norway has proposed opening up a Germany-sized part of the Norwegian Sea to deep-sea mining.

The Norwegian government and industries say they will take a precautionary approach to this deep-sea mining.

However, critics say plans should be progressing more slowly to properly assess the marine environment and the possible impacts of mining, and the Norwegian government received numerous responses during a public consultation period arguing that the country should not mine its deep sea.

Norway is moving forward with plans to mine its continental shelf to procure minerals critical for renewable energy technologies. However, some scientists, members of civil society and even industry leaders have raised concerns about Norway’s proposal, arguing that deep-sea mining in this part of the ocean could cause widespread environmental harm.

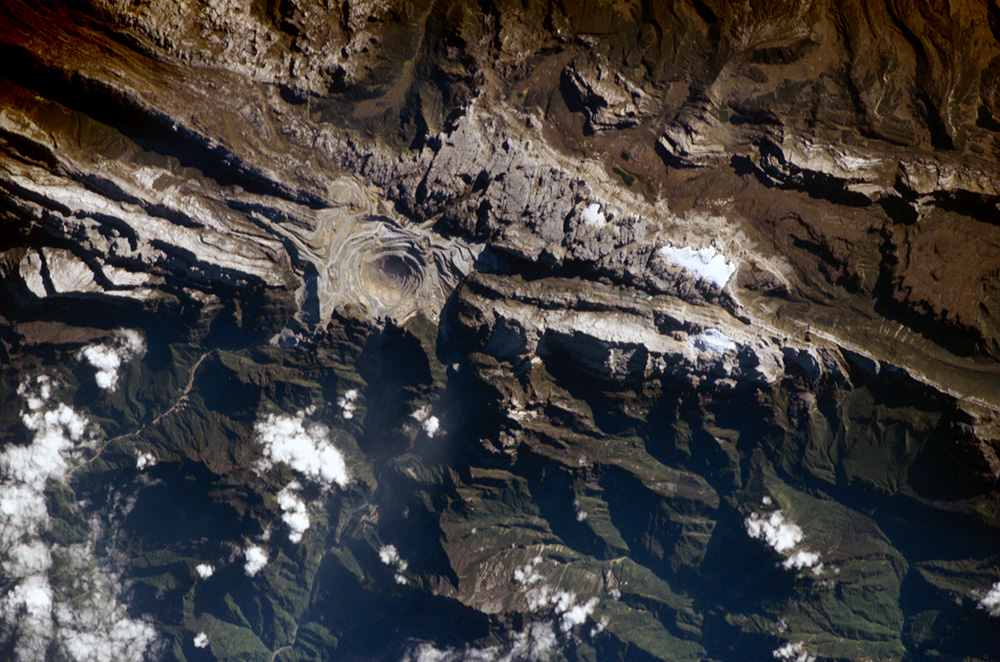

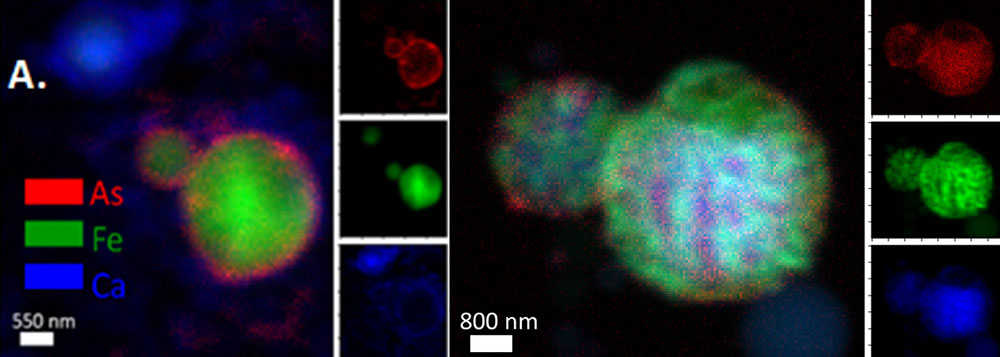

The nation’s Ministry of Petroleum and Energy has proposed opening up a 329,000-square-kilometer (127,000-square-mile) portion of the Norwegian Sea to deep-sea mining, an area nearly the size of Germany. The region overlaps with many marine areas previously flagged by Norwegian research institutes and government agencies as vulnerable or valuable. A study by the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD), a government agency responsible for regulating petroleum resources, found that this area holds significant quantities of minerals such as magnesium, cobalt, copper, nickel and rare-earth metals. Investigators found these minerals on manganese crusts on seamounts and sulfide deposits on active, inactive or extinct hydrothermal vents at depths of 700-4,000 meters (2,296-13,123 feet).

A sliver of this proposed mining area is within Norway’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The rest falls across the adjoining continental shelf — the gently sloping seabed stretching out from Norway’s mainland into the ocean — in international waters beyond Norway’s jurisdiction. However, Norway gained access to the continental shelf that borders its EEZ in 2009 after filing an application with the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, a U.N. body that manages extended access to the nations’ continental shelves. Norway’s access applies only to the seabed, not the water column or surface waters above the continental shelf.

In 2021, the Norwegian government began working on a mining impact assessment and released it for public consultation in October 2022. It received more than 1,000 responses, most from individuals, research institutes, environment agencies and other groups expressing opposition to Norway’s deep-sea mining plans.

One response came from the Norway Environment Agency, a government bureau under the Ministry of Climate and Environment. The agency raised several issues with the impact assessment, including that it did not provide adequate information about how mining could be done safely and sustainably. The agency argued that this omission violates the country’s Seabed Minerals Act, a legal framework created in 2019 for surveying and extracting minerals on the Norwegian continental shelf.

Now that the public consultation process has finished, the decision whether to open Norway’s EEZ and continental shelf to deep-sea mining sits with the federal government. If the government does open the area, Norway could become one of the first nations to initiate deep-sea mining in its nearby waters. A few other countries, including China, Papua New Guinea, the Cook Islands and New Zealand, have explored starting similar projects, but none have begun full-scale exploitation. According to the Cook Islands Seabed Minerals Authority, a government agency responsible for regulating seabed minerals, the country has issued exploration licenses to obtain “the information necessary to inform future decisions about whether it will allow mining to commence in line with the precautionary approach.” In the case of New Zealand, its supreme court blocked a proposed seabed mining operation in 2021, generating a major stumbling block for the industry.

‘Enormous supply gap’

Walter Sognnes, the CEO of Loke Marine Minerals, one of three companies looking to mine Norway’s continental shelf, said he believes the deep sea is key to supplying the “increasing demand” for critical minerals. Loke is aiming to mine manganese crusts that occur on seamounts on Norway’s continental shelf, believed to hold cobalt and rare-earth metals worth billions of dollars.

“We need to solve this enormous supply gap that is coming … and we think deep-sea minerals are the right way to go,” Sognnes told Mongabay.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), today’s mineral supply will fall short of what’s needed to transform the energy sector, resulting in a delayed and more expensive transition to renewable technologies. A recent study in Nature Communications likewise suggested that demand will escalate as countries work to replace gas-combustion vehicles with electric ones. For instance, it suggested that if nations aim to make all vehicles electric by 2050, the global demand will increase by 7,513% for lithium, 5,426% for nickel, 2,838% for manganese and 2,684% for cobalt. The study also pointed out that most of these critical minerals were available only in “a few politically unstable countries such as Chile, Congo, Indonesia, Brazil, Argentina, and South Africa.”

While environmental experts argue that industries can obtain minerals through means such as battery recycling, Sognnes said he doesn’t think that will become a viable option for at least a couple of decades.

Mineral supply chains can also be complicated by geopolitical tensions with countries like China and Russia, which currently generate many critical minerals, Sogness said.

“You have to look at the alternatives,” he said. “We believe that if you apply the best technology and work together [to protect] the environment, deep-sea minerals can be a better alternative, both on ESG rating, but also on the geopolitical side, you can have a resource that makes us less dependent on China.”

An ESG rating is a measure of how well a company addresses environmental, social and governance risks

Sognnes said if Norway does open its continental shelf, Loke would not begin mining until early in the 2030s. He said it would first be necessary to map and explore the seabed and develop the best possible technologies. Loke plans to use excavation tools, thrusters and pumps to “scrape” the manganese crusts then transport them to a collection vessel.

Some researchers have suggested that plumes generated from deep-sea mining extraction could be highly destructive by distributing sediment and dissolved metals across large swaths of the ocean, which would threaten organisms and introduce heavy metals into the pelagic food chain. However, Sognnes said he does not expect Loke’s crust cutting and collection to generate plumes.

Loke also recently acquired UK Seabed Resources (UKSR), a deep-sea mining firm formerly owned by U.S. global security company Lockheed Martin. This acquisition has given Loke full ownership of two exploration licenses and partial ownership of another in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the Pacific Ocean. This proposed mining would focus on extracting polymetallic nodules, which are potato-shaped rocks containing critical minerals like manganese, nickel, cobalt and copper. Since the CCZ is located in international waters beyond any nations’ jurisdictions, mining activities there are regulated by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a U.N.-affiliated body tasked with protecting the marine environment while ensuring nations receive equal access to minerals.

While the ISA has yet to issue an exploitation license for deep-sea mining, it is working to finalize a set of regulations that could allow mining to start as early as next year — a move that has garnered criticism from governments, civil society organizations, research institutes and many other individuals and groups. Those in opposition say that not enough is known about the deep sea to accurately assess the impacts of mining, and that mining technology is not advanced enough to minimize harm. Additionally, critics say what is known about the deep sea suggests that mining could cause irreversible harm to habitats and species that are essential to the functioning of the ocean.

Some nations and delegates to the ISA are calling for a “precautionary pause” or a moratorium on deep-sea mining until more research is conducted on the deep sea and the possible impacts of mining. France has even called for an outright ban.

Norway, an ISA council member, has generally supported swiftly completing the international mining regulations but stated at recent ISA meetings that no mining should proceed without the “necessary knowledge about ecosystems.”

Other Norwegian companies looking to mine in Norway include ADEPTH Minerals and Green Minerals. While Norwegian energy company Equinor previously expressed interest in deep-sea mining, the company called for a “precautionary approach” during the public consultation, saying experts must have sufficient time to properly understand the possible environmental consequences of deep-sea mining.

‘Too quick and too big’

Peter Haugan, a scientist who serves as policy director of Norway’s Institute of Marine Research and director of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen, said the Norwegian government should not rush mining in the country’s continental shelf.

“Jumping right into mining and opening big areas for exploration first with the implication that there will be mining is a bit too quick and too big,” Haugan told Mongabay. “Normally, when we think about new industries that may be moving into areas in the ocean, we typically take small steps.”

Haugan said that while some academic research has been conducted on features like hydrothermal vents in the proposed mining area, more is needed to understand this deep-sea environment, the water column and the organisms that live there. Before mining is allowed to proceed, he said researchers need to conduct extensive baseline studies to understand the impacts for both the mining area and the wider environment, which would be hard to do within short timespans.

“It’s very difficult to imagine that a single company getting a license for a small area will be prepared to do the environmental baseline that is needed in their area and in the surrounding areas, which may be affected and which may have connected ecosystems,” Haugan said.

According to an assessment by the Institute of Marine Research, there is a lack of information for 99% of the proposed mining area.

Kaja Lønne Fjærtoft, a marine biologist and global policy lead at WWF, told Mongabay it’s difficult to “nail down the actual consequence” of deep-sea mining on the Norwegian shelf without more knowledge of the environment, technology and mining impacts. Based on what is known, she said there is concern that mining manganese crusts or sulfide deposits could have widespread effects on species through the destruction of habitat, generation of harmful plumes and noise pollution. (Sognnes of Loke, however, said his company’s proposed operations would not target unique habitats or generate plumes and would produce minimal noise.)

Transboundary concerns

Norway’s plans also raise several transboundary concerns. For one, mining activities could impact fisheries operating in the water above the extended continental shelf, Fjærtoft said.

“We don’t have exclusive rights to fisheries above it, so the mining that could happen in the seabed could impact international fisheries because most of the [proposed mining] areas are also in areas where like the U.K. would be fishing, the EU would be fishing,” she said. “And that’s not really accounted very well for in the impact assessment.”

According to 2019 data, the U.K. and several EU countries fish in the proposed deep-sea mining area, targeting species like shrimp, cod, sole, haddock and mussels.

Norway submitted its impact assessment to Denmark and Iceland in accordance with the Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment, which requires parties to disclose if activities could cause transboundary environmental harm. Denmark’s Environmental Protection Agency wrote a letter to the Norwegian Environment Agency, arguing that the mining’s possible effects on seabirds and marine mammals have not been thoroughly investigated, according to documents reviewed by Mongabay.

Another issue is that part of Norway’s proposed mining area falls across the continental shelf of Svalbard, an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. The Svalbard Treaty, which 48 countries have ratified, recognizes Norway’s sovereignty over Svalbard but also specifies that parties have equal rights to engage in commercial activities there. However, in a letter viewed by Mongabay, Iceland’s Ministry for Foreign Affairs informed the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that the exploitation of any mineral resources on Svalbard’s continental shelf was “subject to the provisions of the Svalbard Treaty, including the principle of equality.” In other words, Norway couldn’t claim sole ownership of these resources.

“If Norway actually goes ahead with extraction of seabed minerals, it will be the first time the Svalbard Treaty — in terms of extractive seabed resources, including oil and gas — is tested in that region,” Fjærtoft said. “This will set precedent for future potential oil and gas extraction in this area.”

Fjærtoft also argues that Norway’s plans for deep-sea mining contradict its commitments as a founding member of the Ocean Panel, a global initiative that aims to help member nations “sustainably manage” 100% of their national marine waters by 2025.

In a paper, the Ocean Panel stated that nations should take a precautionary approach to deep-sea mining and that regulations and knowledge should be in place by 2030 to “to ensure that any activity related to seabed mining is informed by science and ecologically sustainable.”

More recently, Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre, the current head of the Ocean Panel, said in an interview with a Norwegian paper in March that deep-sea mining can be one of three sustainable ocean actions Norway can set in motion and that deep-sea mining could be done in a way that doesn’t harm marine biodiversity. Støre’s comments garnered criticism from environmental NGOs.

Haugan, who serves as co-chair of the Ocean Panel’s Expert Group, said the Norwegian government’s course technically satisfies the panel’s “not very precise” statement directing a precautionary approach to deep-sea mining. However, he said he was still concerned about how quickly things were moving.

“There is a real fear that the quality and quantity of those environmental investigations will not be sufficient,” Haugan said. “And therefore, there’s this big danger that this will run off and lead to inappropriate actions in the deep sea.”

What happens next?

Amund Vik, state secretary of Norway’s Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, the body forwarding the proposal to mine, told Mongabay the impact assessment, consultation impact and resource report from NPD “will form an important part of the decision basis on whether to open areas” to deep-sea mining. However, he emphasized that a decision to open the area wouldn’t necessarily result in commercial activities. Vik also said the government will submit a white paper about the issue to parliament in “spring.”

“A comprehensive permitting regime has been established in Norwegian legislation, and this regime is based upon a stepwise approach to allowing commercial activities to take place,” Vik said in an emailed statement. “Seabed mineral activities will only take place if it can be done in a prudent and sustainable manner.”

However, Fjærtoft said she believes if and when the Norwegian government does approve the opening of the proposed mining area, commercial activities could quickly begin. The nation’s Seabed Minerals Act specifies that companies may immediately apply for exploitation licenses alongside exploration licenses. According to Fjærtoft, companies are likely to opt for exploitation licenses because they confer exclusive rights to an area; exploration licenses, on the other hand, are nonexclusive.

“Norway could be the first country to give an exploitation license,” Fjærtoft said. “If they do that, that is heavily criticizable because you definitely do not have enough knowledge to be able to assess anything on the impact of exploitation. You don’t even have enough to assess impacts of exploration.”

Elizabeth Claire Alberts is a senior staff writer for Mongabay. Follow her on Twitter @ECAlberts.

Banner image: Walruses in Svalbard, Norway — a vulnerable area. Image by Gregoire Dubois via Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Citations:

The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions. (2021). Retrieved from International Energy Agency website: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary

Zhang, C., Zhao, X., Sacchi, R., & You, F. (2023). Trade-off between critical metal requirement and transportation decarbonization in automotive electrification. Nature Communications, 14(1). doi:10.1038/s41467-023-37373-4

Transformations for a Sustainable Ocean Economy: A Vision for Protection, Production and Prosperity. (2022). Retrieved from High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy website: https://oceanpanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/transformations-sustainable-ocean-economy-eng.pdf