By Rodielon Putol

Earth.com staff writer

Recent PhD research conducted at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean has revealed new insights into the potential impacts of deep-sea mining on marine life.

Marine geologist Sabine Haalboom’s findings illustrate that while much of the debris from mining activities — referred to as ‘dust clouds’ — settles relatively close to its source, a notable portion spreads far into the water.

This research, carried out in the Clarion Clipperton Zone, provides a crucial understanding of how mining operations could affect these pristine environments. Haalboom defended her dissertation on this topic at Utrecht University, highlighting significant concerns for deep-sea ecosystems.

Deep-sea mining and marine life

The depths of the ocean harbor unique ecosystems, with conditions and life forms that remain largely mysterious to scientists. These ecosystems are often fragile and sensitive to changes in their environment.

Deep-sea mining, particularly the extraction of valuable metals like manganese nodules, disturbs the ocean floor’s silt. This process can create extensive dust clouds, clouding the water over vast areas and potentially impacting these pristine habitats.

Given our limited understanding of deep-sea life, these disturbances could have unforeseen effects on the delicate underwater communities. The organisms living in these depths rely on specific environmental conditions for survival. Any alteration, even minor, could disrupt their way of life, leading to unknown consequences.

The potential impact of deep-sea mining on biodiversity and marine ecosystem functions remains a significant concern. Therefore, deep-sea mining’s environmental footprint needs careful consideration.

Researchers stress the importance of thorough studies to understand the full implications before engaging in large-scale mining operations in these unexplored and vulnerable areas.

Deep-sea mining’s environmental footprint

Haalboom utilized various instruments to measure the quantity and size of suspended particles in the ocean water. Her experiments took place in the Clarion Clipperton Zone, an area rich in manganese nodules.

She dragged a 500-kilogram grid of steel chains across a 500-meter stretch of the seabed. This action stirred up a significant amount of sediment, resulting in immediate murkiness in the water.

Initially, most of this stirred-up material settled quickly, within a few hundred meters of the disturbance site. This quick settling suggested that the immediate impact of mining activities might be localized. However, further observations revealed a different aspect.

A small fraction of the sediment did not settle quickly and remained suspended in the water. This suspended sediment was visible even hundreds of meters away from the initial disturbance.

These findings highlight the potential for deep-sea mining activities to affect broader areas of the marine environment, emphasizing the need for thorough research before large-scale mining operations proceed.

Further studies have shown that these “dust clouds” can travel up to five kilometers from the original mining site. This persistence poses a potential threat to the clarity of the water, which is typically crystal clear and vital for the survival of local marine life.

The scarce food available in these clear waters is crucial for the organisms that inhabit the deep sea, making even small changes to their environment potentially impactful.

Additional consequences

Deep-sea mining poses additional risks. It can disrupt habitats, leading to the loss of biodiversity. The noise and vibrations from mining equipment can affect marine life, particularly species reliant on echolocation.

Deep-sea mining activities can release toxic substances trapped in seabed sediments, contaminating the water and harming marine organisms. The physical removal of substrate can destroy slow-growing deep-sea corals and sponges, critical for ecosystem health.

Additionally, the increased human activity could introduce invasive species, further threatening native marine life. These potential impacts underscore the need for cautious, well-informed approaches to deep-sea mining.

Need for research in deep-sea mining

Haalboom’s co-promoter, NIOZ oceanographer Henko de Stigter, has expressed concern over the rapid commercial interest in deep-sea mining. He argues that the initial findings of quick sediment settling do not capture the full potential impact of these mining activities on deep-sea ecosystems.

The long-term effects of even minimal sediment dispersal are still unknown, prompting both Haalboom and De Stigter to advocate for more extensive research before proceeding with large-scale mining operations.

In conclusion, while deep-sea mining presents a tempting opportunity to extract valuable resources, the potential risks to unknown marine ecosystems and the broader environmental impacts demand careful consideration.

The call for further study is clear: we must fully understand the consequences of our actions in these remote, unexplored parts of our planet before making irreversible decisions.

Monitoring strategies of suspended matter after natural and deep-sea mining disturbances

"Dust clouds" at the bottom of the deep sea, that will be created by deep-sea mining activities, descend at a short distance for the most part. That is shown by Ph.D. research of NIOZ marine geologist Sabine Haalboom, on the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

Yet, a small portion of the stirred-up bottom material remains visible in the water at long distances. "These waters are normally crystal clear, so deep-sea mining could indeed have a major impact on deep-sea life," Haalboom states in her dissertation that she defends at Utrecht University on May 31.

Currently, the international community is still discussing the possibilities and conditions for mining valuable metals from the bottom of the deep sea. This so-called deep-sea mining may take place at depths where very little is known about underwater life.

Among other things, the silt at the bottom of the deep sea, which will be stirred up when extracting manganese nodules, for example, is a major concern. Since life in the deep sea is largely unknown, clouding the water will definitely create completely unknown effects.

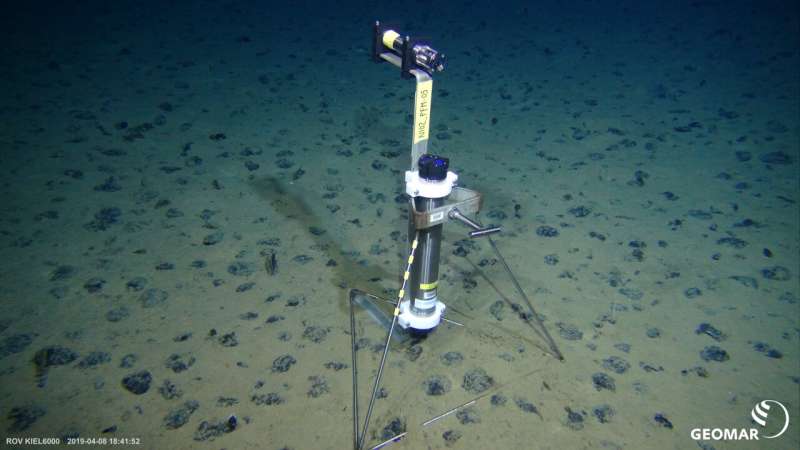

For her research, Haalboom conducted experiments with different instruments to measure the amount and also the size of suspended particles in the water. At the bottom of the Clarion Clipperton Zone, a vast area in the depths of the Pacific Ocean, Haalboom performed measurements with those instruments before and after a grid with 500 kilograms of steel chains had been dragged across the bottom.

"The first thing that strikes you when you take measurements in that area, is how unimaginably clear the water naturally is," Haalboom says.

"After we dragged the chains back and forth over a 500-meter stretch, the vast majority of the stirred-up material settled within just a few hundred meters. Yet, we also saw that a small portion of the stirred-up bottom material was still visible up to hundreds of meters from the test site and meters above the bottom. The water was a lot murkier than normal at long distances from the test site."

In a follow-up study, in which Ph.D. candidate Haalboom was not involved, the "dust clouds" were visible even up to five kilometers away from the test site.

International companies that are competing for concessions to extract the scarce metals from the deep-sea floor, are seizing on the results of these initial trials as an indication of the low impact of deep-sea mining on bottom life. Yet, that is not justifiable, says the co-promoter of Haalboom's research, NIOZ oceanographer Henko de Stigter.

"Sure, based on this Ph.D. research and also based on follow-up research, we know that the vast majority of the dust settles quickly. But when you take in consideration how clear these waters normally are, and that deep-sea life depends on the very scarce food in the water, that last little bit could have a big impact," he says.

Both Haalboom and De Stigter urge more research before firm statements can be made about the impact of deep-sea mining. "It is really too soon to say at this point how harmful or how harmless that last bit of dust is that can be spread over such great distances", de Stigter emphasizes.

More information: Monitoring Strategies of Suspended Matter after Natural and Deep-Sea Mining Disturbances, (2024). DOI: 10.33540/2217

Provided by Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research

FULL STORY

'Dust clouds' at the bottom of the deep sea, that will be created by deep-sea mining activities, descend at a short distance for the biggest part. That is shown by PhD research of NIOZ marine geologist Sabine Haalboom, on the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Yet, a small portion of the stirred-up bottom material remains visible in the water at long distances. "These waters are normally crystal clear, so deep-sea mining could indeed have a major impact on deep-sea life," Haalboom states in her dissertation that she defends at Utrecht University on May 31st.

Unidentified Living Organisms between manganese nodules

Currently, the international community is still discussing the possibilities and conditions for mining valuable metals from the bottom of the deep sea. This so-called deep-sea mining may take place at depths where very little is known about underwater life. Among other things, the silt at the bottom of the deep sea, which will be stirred up when extracting manganese nodules, for example, is a major concern. Since life in the deep sea is largely unknown, clouding the water will definitely create completely unknown effects.

Variety of instruments

For her research, Haalboom conducted experiments with different instruments to measure the amount and also the size of suspended particles in the water. At the bottom of the Clarion Clipperton Zone, a vast area in the depths of the Pacific Ocean, Haalboom performed measurements with those instruments before and after a grid with 500 kilograms of steel chains had been dragged across the bottom.

Still murky for a long time

"The first thing that strikes you when you take measurements in that area, is how unimaginably clear the water naturally is," Haalboom says. "After we dragged the chains back and forth over a 500-meter stretch, the vast majority of the stirred-up material settled within just a few hundred meters. Yet, we also saw that a small portion of the stirred-up bottom material was still visible up to hundreds of meters from the test site and meters above the bottom. The water was a lot murkier than normal at long distances from the test site."

In a follow-up study, in which PhD candidate Haalboom was not involved, the 'dust clouds' were visible even up to five kilometers away from the test site

Scarce food in clear water

International companies that are competing for concessions to extract the scarce metals from the deep-sea floor, are seizing on the results of these initial trials as an indication of the low impact of deep-sea mining on bottom life. Yet, that is not justifiable, says the co-promoter of Haalboom's research, NIOZ oceanographer Henko de Stigter. "Sure, based on this PhD research and also based on follow-up research, we know that the vast majority of the dust settles quickly. But when you take in consideration how clear these waters normally are, and that deep-sea life depends on the very scarce food in the water, that last little bit could have a big impact."

Too early to decide

Both Haalboom and De Stigter urge more research before firm statements can be made about the impact of deep-sea mining. "It is really too soon to say at this point how harmful or how harmless that last bit of dust is that can be spread over such great distances," De Stigter emphasizes.

Story Source:

Materials provided by Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research. Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

A precautionary tale: Exploring the risks of deep-sea mining

Introduction

Deep-sea mining, which is the process of mining precious metals from below the deep seafloor, is a relatively new industry. This industry is thought to be profitable and alluring, because the metals in the deep sea can be used in batteries for electronics. There are three types of valuable metal deposits located within the deep sea, and these include polymetallic nodules, cobalt crusts, and seafloor massive sulfides [11], [14]. Each of these deposits are rich in cobalt, copper, manganese, nickel, and other metals, which are frequently used in batteries for electronics [14], [6]. These metals are mined using a three-phase process: prospecting, exploration, and exploitation [10]. To date, there has been no exploitation of the deep sea [9].

Discovered in the late 1950 s, the deep-sea was seen to contain an endless supply of valuable metals that would one day lead to the end of terrestrial mining [5], [6]. Throughout the 1970 s, ships were deployed to the Pacific Ocean in hopes of finding ways to extract the battery metals from the seabed [5], [6]. However, due to a lack of technology with the ability to extract the metals from the seafloor, deep-sea mining became impossible at that time [5], [6].

Today, deep-sea mining has gained a renewed interest, and it can take place in either coastal countries’ exclusive economic zones (EEZs) or in the International Seabed Authority’s Area [1], [3]. In EEZs, current deep-sea mining explorations take place in Papua New Guinea, Fiji, The Cook Islands, and Nauru. Mining in the high seas is under the jurisdiction of the International Seabed Authority.1

Deep-sea mining does not come without potentially devastating environmental risks [7], [11], [13], [18], [2]. There are thousands of species that are threatened by the disruption deep-sea mining will bring to their ecosystem [13], [18], [2]. While there has been some work to protect ecosystems in the deep sea, scientist still do not know the full impact of deep-sea mining on the environment [7], [11], [12], [13], [18], [2].

Mining operations can have an impact not only on the deep sea, but the ocean in general [7], [11], [13]. Mining equipment is loud, disruptive on the surface of the ocean floor and the top surface of the ocean, and it gives off heavy light pollution [7], [11]. Additionally, mining equipment often stirs up sediments that can dislocate animals or create clouds of dust [11], [12]. When this dust settles, it can harm and possibly kill filter-feeders at the bottom of the ocean that rely on clean water flow [11], [12]. According to Greenpeace International [7], fish stocks will be endangered by the disruption on the surface of the ocean. Furthermore, the burden will fall on communities, which are disproportionately in the global south, that rely on fish stocks for economic means or for food [7]. Lastly, deep-sea mining can release carbon that is normally absorbed by the sea into the atmosphere [7].

In addition to biological impacts, deep-sea mining can significantly affect the chemical composition of the deep sea [11]. This is because extracting manganese can release toxic metals into the marine environment. Additionally, because metal extraction happens vertically, deep sea water is extracted along with the minerals and is often discharged either along the way or at the top of the ocean [11], [12]. The composition of this water can be different than that at the surface, and this can be disruptive to the ecosystem on the ocean surface (Koschinksy et al., 2018).

To combat threats to ecosystems, scientists have developed deep-sea restoration projects [18], [2]. For example, species, like cold water corals, are taken out of the deep-sea environment, placed in labs where they grow, and then reintroduced to the seafloor [2]. While experiments have shown that, after three years of post-reintroduction, 76% of corals survived [2], scientists do not know how successful large-scale restorations would be [18], [2]. Barbier et al. [2] point out that current knowledge is not promising, calling on research that was done on freshwater restoration. Four decades after freshwater restoration, ecosystems do not recover the full biodiversity as they had before disruption [2]. Another study with similar results was conducted in the Peru Basin [11]. The study removed manganese sediments, as a commercial deep-sea mining company would, to understand the environmental cost (Koschinksy et al., 2018). They found that mining caused permanent damage to the habitat [11]. Furthermore, costs for restoration can be very expensive. One estimate suggests that it would cost 75 million USD to restore one hectare of seabed in the Darwin Mounds in the Northeast Atlantic [2]. Overall, the environmental cost of deep-sea mining is not small, and it can be drastic if deep-sea mining begins before we truly understand its impact on the ocean.

Roche and Bice (2013) argue that the social costs of deep-sea mining will be very similar to the social costs of terrestrial mining. Social impacts of mining highly depend on the location and how long the project is expected to last (Roche & Bice, 2013). While there are uncertainties surrounding the social costs of deep-sea mining due to the fact that deep sea mining is yet to occur, some researchers have begun assessing both the potential costs and the benefits. In terms of costs, some argue that developing nations can: (a) see their economies be taken over by foreign corporations of the countries that received the permits to mine within their EEZs; (b) experience increased demands on infrastructure, such as ports, causing strain to these nations; and (c) witness potential displacement of local fishers (Roche & Bice, 2013). Additionally, a cost-benefit analysis conducted by the European Parliament Research Service concluded that while deep-sea mining is foreseen to generate fewer economic opportunities and jobs, it is likely to have substantial impacts on these communities, especially if “fish stocks are affected or if land-based processing practices of mining-related activities are not controlled” ([17], p. 55). Koschinsky et al. [11] warn that this does not take into account the fact that plumes of sediment from the deep-sea can travel far beyond the deep-sea mining site, impacting fishing by polluting the environment of the fish. Others suggest that the social costs of deep-sea mining can be situational: for example, a cost-benefit analysis conducted by Wakefield and Myers [19] found that allowing for deep-sea mining for sulfide deposits in Papua New Guinea and manganese modules in Cook Islands has the potential to improve the well-being of the people in these nations, nevertheless the same cannot be concluded for cobalt mining in the Marshall Islands, as such activity is not likely to improve the well-being of the communities in this nation.

It is important to acknowledge that ‘social cost’ does not inherently imply a negative connotation. Terrestrial mining has benefitted, in some capacity, developing countries by boosting education and healthcare access and quality, by allowing community members to participate in the economy by owning better homes or opening businesses, and by affording opportunities for women to get involved (Roche & Bice, 2013). Deep-sea mining may have similar impacts. For example, Wakefield and Meyers (2018) predicted that deep-sea mining on the Cook Islands would lead to 150 jobs for 20 years. While this number may appear small, when taking into account how small the Cook Island’s workforce is, 150 jobs is actually a 2% increase in employment (Wakefield & Meyers, 2018). All social implications as they apply to deep-sea mining are yet to be seen, but these need to be taken into consideration before deep-sea mining exploration actually begins [8], [4].

As it can be seen, deep-sea mining comes with some known environmental and social impacts [7], [11], [2], however, studies on the risks associated with deep-sea mining remain scarce. This paper fills one gap in this research by focusing on examining data on 21 countries that have been given mining exploration permits by the International Seabed Authority (see Appendix 1 for a list of these countries). The risks are assessed in terms of their international commitments through the ratification/signing of international treaties, as well as through their performance on various risk indices. This paper argues that the overall lack of good-faith commitment through clear demonstration of ratification of relevant international treaties, in combination with various performance indices of risk (as assessed by third parties, such as the World Bank), should be a warning sign and be taken into consideration when issuing permits for deep-sea mining.

Section snippets

Researh methods

To achieve the goal outlined above, this research collected data on all 21 nations that have a contract with the ISA. The data were separated into two subcategories: commitments to UN and other International Conventions; and Other Risk Indicators. The following section will lay out the conventions and other indicators for which data were collected, summarized, and analyzed in this research.

Ratification of major international conventions

For the purposes of this research and its scope, we have identified a total of 17 international conventions. These fell into four different groupings, including sea conventions (n=5), IUU-fishing related conventions (N=3), climate conventions (n=4), and transnational organized crime-related (TOC) conventions (n=5). The 21 countries that have been given permission for deep-sea mining have performed relatively differently in terms of their commitment to these conventions. Of the 17 conventions,

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Gohar A. Petrossian: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Jess Lettieri: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

References (20)

- et al.

Mining of deep-sea seafloor massive sulfides: a review of the deposits, their benthic communities, impacts from mining, regulatory frameworks and management strategies

Coast. Manag.

(2013) - et al.

News from the seabed – Geological characteristics and resource potential of deep-sea mineral resources

Mar. Policy

(2016) Preventing illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing: a situational approach

Biol. Conserv.

(2015)A micro-spatial analysis of opportunities for IUU fishing in 23 Western African countries

Biol. Conserv.

(2018)- et al.

Social cost benefit analysis for deep sea minerals mining

Mar. Policy

(2018) How can life in the deep sea be protected?

Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law

(2009)- et al.

Ecology: protect the deep sea

Nature

(2014) - et al.

Ocean Coast. Manag.

(2020) Deep-sea mining: historical perspectives

Economic geology: lessons learned from deep-sea mining

Science

(2000)