Children's books solidify gender stereotypes in young minds

A new study from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison has found children's books may perpetuate gender stereotypes. Such information in early education books could play an integral role in solidifying gendered perceptions in young children. The results are available in the December issue of the journal Psychological Science.

"Some of the stereotypes that have been studied in a social psychology literature are present in these books, like girls being good at reading and boys being good at math," said Molly Lewis, special faculty in the Social and Decision Sciences and Psychology departments at the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences and lead author on the study.

Lewis has found that books with gendered language were centered around the protagonist in the story. Female-associated words focused on affection, school-related words and communication verbs, like 'explained' and 'listened.' Meanwhile, male-associated words focused more on professions, transportation and tools.

"The audiences of these books [are] different," said Lewis. "Girls more often read stereotypically girl books, and boys more often read stereotypically boy books."

Girls are more likely to have books read to them that include female protagonists than boys. Because of these preferences, children are more likely to learn about the gender biases of their own gender than of other genders.

The researchers analyzed 247 books written for children 5 years old and younger from the Wisconsin Children's Book Corpus. The books with female protagonists had more gendered language than the books with male protagonists. The researchers attribute this finding to "male" being historically seen as the default gender. Female-coded words and phrases are more outside of the norm and more notable.

The researchers also compared their findings to adult fiction books and found children's books displayed more gender stereotypes than fictional books read by adults. In particular, the researchers examined how often women were associated with good, family, language and arts, while men were associated with bad, careers and math. Compared to the adult corpus, which was fairly gender neutral when it came to associations between gender, language, arts and math, children's books were far more likely to associate women with language and arts and men with math.

"Our data are only part of the story—so to speak," said Mark Seidenberg, professor of psychology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and contributing author on the study. "They are based on the words in children's books and say nothing about other characteristics that matter: the story, the emotions they evoke, the ways the books expand children's knowledge of the world. We don't want to ruin anyone's memories of 'Curious George' or 'Amelia Bedelia.' Knowing that stereotypes do creep into many books and that children develop beliefs about gender at a young age, we probably want to consider books with this in mind."

The study did not directly assess how children perceive the messages about gender in these books or examine how the books influence how the readers perceive gender. The study also did not evaluate other sources of gender stereotypes to which children are exposed.

"There is often kind of a cycle of learning about gender stereotypes, with children learning stereotypes at a young age then perpetuating them as they get older," said Lewis. "These books may be a vehicle for communicating information about gender. We may need to pay some attention to what those messages may be and whether they're messages you want to even bring to children."

Lewis and Seidenberg were joined by Matt Cooper Borkenhagen, Ellen Converse and Gary Lupyan from the University of Wisconsin, Madison in the study, titled "What books might be teaching young children about gender?"60 years of children's books reveal persistent overrepresentation of male protagonists

More information: What books might be teaching young children about gender? Psychological Science (2021).

Journal information: Psychological Science

Provided by Carnegie Mellon University

60 years of children's books reveal persistent overrepresentation of male protagonists

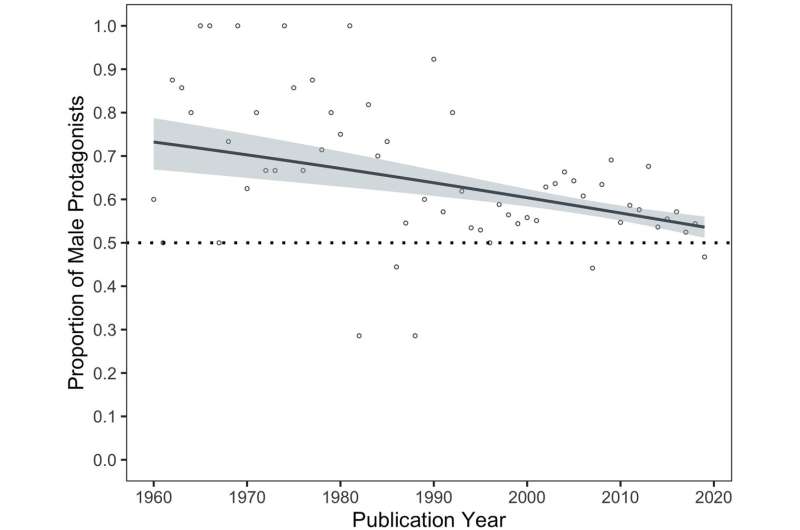

An analysis of thousands of children's books published in the last 60 years suggests that, while a higher proportion of books now feature female protagonists, male protagonists remain overrepresented. Stella Lourenco of Emory University, U.S., and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on December 15, 2021 and explore the factors associated with representation

A large body of evidence points to a bias in male versus female representation among protagonists in children's books published prior to 2000. However, evidence is lacking as to whether that bias has persisted. In addition, it has been unclear which factors, such as author gender, may be associated with male versus female protagonists.

To help clarify whether gender bias still exists in American children's literature, the authors conducted a statistical analysis of the frequency of male versus female protagonists in 3,280 books, aimed for audiences aged 0 to 16 years and published between 1960 and 2020. They selected books that can be purchased online in the United States, either as hard copies or as digital books, and primarily written in English (<1% written in multiple languages). To enable direct comparison of the rates of appearance of male versus female central characters, they focused on books featuring a single central protagonist, and also only included books for which the gender of the book author was identifiable and matched for all authors if there was more than one.

The analysis found that, since 1960, the proportion of female central protagonists has increased—and is still increasing—but books published since 2000 still feature a disproportionate number of male central protagonists.

The researchers also found associations between the ratio of male versus female protagonists and several relevant factors. Specifically, they found that gender bias is higher for fiction featuring non-human characters than for fiction with human characters. Meanwhile, non-fiction books have a greater degree of gender bias than fiction books, especially when the characters are human.

Books by male authors showed a decline in bias since 1960, but only in books written for younger audiences. Books by female authors also declined in bias over time, ultimately with more female than male central protagonists featured in books for older children and in books with human characters.

These findings could help guide efforts toward more equitable gender representation in children's books, which could impact child development and societal attitudes. Future research could build on this work by considering reading rates of specific books, as well as books with non-binary characters.

The authors add: "Although male protagonists remain overrepresented in books written for children (even post-2000), the present study found that the male-to-female ratio of protagonists varied according to author gender, age of the target audience, character type, and book genre. In other words, some authors and types of books were more equitable in the gender representation of protagonists in children's books."

Learning to read starts earlier than you might think: Five tips from an expert

In the early weeks of their lives and even before birth, babies are skilfully processing important information about the sounds they hear. They are attuning to tones, patterns of language and distinguishing their own familiar adults' voices. Making sense of sounds, patterns, words and sentences are important skills that will help a child as they progress towards reading.

Early reading for under-threes is rooted in their daily lives. It involves lots of listening, communication, speech and language activities—not just sharing books.

As their language and communication skills develop and they build vocabulary, under-threes learn to use pictures, words and sounds, tell and retell familiar stories, and sing songs and rhymes. In turn, these activities help children navigate pictures, words and sentences they encounter on the page.

Here are five tips to support early reading for children aged under three.

1: Create a "chatty" environment

Encourage and support lots of communication. Research shows that talking to babies and toddlers helps them build vocabulary, while conversation a child simply overhears does not always contribute to their vocabulary development.

Take turns in conversations and comment on their activities and the routines of the day. This could be when getting dressed, during play, nappy changing or taking a walk through the park. This will enable under-threes to begin to develop receptive language—the ability to understand others. They will make connections, notice, respond and engage with sounds and images in the environment, all important early reading skills.

2. Have fun with rhythm and music making

Play lots of rhyming games, sing nursery rhymes, comment on rhyming patterns in songs and make lots of music. Repetition and predictable rhyme helps children remember new words.

Alliteration and assonance in poetry and nursery rhymes draws attention to the individual sounds and patterns in words.

3. Share meaningful images

Use images, such as pictures and photographs of familiar places, objects, families and communities, to create meaningful shared experiences for children under three. Make books with photographs or apps to encourage talk and interaction about children's home cultures and families. Encourage children to point out the details they encounter in pictures.

Reading pictures and following images helps children learn to read as they begin to make connections, understand sequences of stories and further develop their comprehension skills. Very young children are adept at interpreting visual texts and noticing details.

4. Draw attention to print in daily life

Use your environment and local community to point out words at home, at nursery or out and about. This could be print on cereal boxes, signs or logos. Encountering print in their environment helps under-threes recognize letters, sounds and images that have meaning.

5. Engage with books frequently

Shared book reading, story time and retelling stories together are valuable points of connection and social interaction for under-threes. When supportive adults encourage the exploration of pictures, draw attention to the text and the conventions of print, and talk about the characters or the sequence of the story, the story comes alive to create awe and wonder for children.

Choose a range of books—cloth, sensory, picture books and story books or online story apps. Ensure that under-threes also have independent access to these, so they are able to choose books or apps themselves, turn pages or handle interactive technology.

Puppets, props and role-play help to make books or stories and rhymes interactive and help children recreate stories through imaginative play. Under-threes need to relate images, sounds and words to their own experiences, so ensure that the props you use link to the child's culture and daily life.

Parents play a key role in fostering children's love of reading

Provided by The Conversation

Cognitive training designed to focus on what's important while ignoring distractions can enhance the brain's information processing, enabling the ability to "learn to learn," finds a new study on mice.

"As any educator knows, merely recollecting the information we learn in school is hardly the point of an education," says André Fenton, a professor of neural science at New York University and the senior author of the study, which appears in the journal Nature. "Rather than using our brains to merely store information to recall later, with the right mental training, we can also 'learn to learn,' which makes us more adaptive, mindful, and intelligent."

Researchers have frequently studied the machinations of memory—specifically, how neurons store the information gained from experience so that the same information can be recalled later. However, less is known about the underlying neurobiology of how we "learn to learn"—the mechanisms our brains use to go beyond drawing from memory to utilize past experiences in meaningful, novel ways.

A greater understanding of this process could point to new methods to enhance learning and to design precision cognitive behavioral therapies for neuropsychiatric disorders like anxiety, schizophrenia, and other forms of mental dysfunction.

To explore this, the researchers conducted a series of experiments using mice, who were assessed for their ability to learn cognitively challenging tasks. Prior to the assessment, some mice received "cognitive control training" (CCT). They were put on a slowly rotating arena and trained to avoid the stationary location of a mild shock using stationary visual cues while ignoring locations of the shock on the rotating floor. CCT mice were compared to control mice. One control group also learned the same place avoidance, but it did not have to ignore the irrelevant rotating locations.

The use of the rotating arena place avoidance methodology was vital to the experiment, the scientists note, because it manipulates spatial information, dissociating the environment into stationary and rotating components. Previously, the lab had shown that learning to avoid shock on the rotating arena requires using the hippocampus, the brain's memory and navigation center, as well as the persistent activity of a molecule (protein kinase M zeta [PKMζ]) that is crucial for maintaining increases in the strength of neuronal connections and for storing long-term memory.

"In short, there were molecular, physiological, and behavioral reasons to examine long-term place avoidance memory in the hippocampus circuit as well as a theory for how the circuit could persistently improve," explains Fenton.

Analysis of neural activity in the hippocampus during CCT confirmed the mice were using relevant information for avoiding shock and ignoring the rotating distractions in the vicinity of the shock. Notably, this process of ignoring distractions was essential for the mice learning to learn as it allowed them to do novel cognitive tasks better than the mice that did not receive CCT. Remarkably, the researchers could measure that CCT also improves how the mice's hippocampal neural circuitry functions to process information. The hippocampus is a crucial part of the brain for forming long-lasting memories as well as for spatial navigation, and CCT improved how it operates for months.

"The study shows that two hours of cognitive control training causes learning to learn in mice and that learning to learn is accompanied by improved tuning of a key brain circuit for memory," observes Fenton. "Consequently, the brain becomes persistently more effective at suppressing noisy inputs and more consistently effective at enhancing the inputs that matter."Trains in the brain: Scientists uncover switching system used in information processing and memory

More information: André Fenton, Cognitive control persistently enhances hippocampal information processing, Nature (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-04070-5. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-04070-5

Journal information: Nature

Provided by New York University

No comments:

Post a Comment