Aaron Sorkin’s Annoying Tics Are Actually Good in The Trial of the Chicago 7By

Alison Willmore MOVIE REVIEW SEPT. 25, 2020

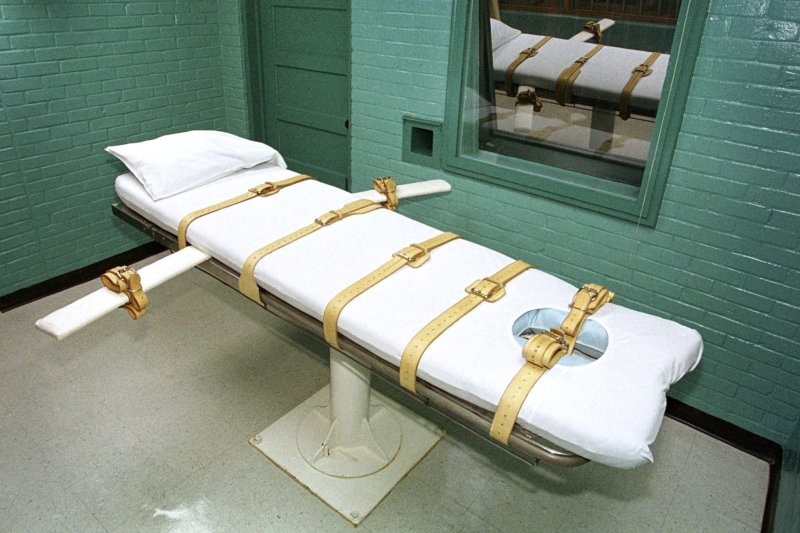

The speeches, the grandstanding, the quips — they totally work in the context of this Netflix courtroom drama. Photo: Niko Tavernise/Netflix

The most maddening, irresistible proposition in an Aaron Sorkin production is that a speech can change hearts and minds. Sorkin loves speech, period — motormouthed walk-and-talks where the cleverness of the characters mitigates the fact that they sound awfully similar, quippy exchanges that ping-pong back around to an eventual callback, arguments that rise in a calculated crescendo until one character breaks into a yell and the room abruptly falls silent. He’s a playwright who moved into film and then television and, more recently, started to direct. The Trial of the Chicago 7, about the protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention and the seven participants who were charged by the federal government with crimes like conspiracy and inciting a riot, is Sorkin’s second venture behind the camera, after Molly’s Game in 2017. But he’ll always be a writer first, and you can see it in his certainty that the correct words, delivered with the proper amount of conviction, can win someone over from the other side of the aisle, even if it’s only one instance — cracking a closed mind open with some carefully crafted sentences.

There are a lot of speeches in The Trial of the Chicago 7, but it’s hard to mind, given what it’s about. This film is one of those exhilarating instances when Sorkin finds a context in which all of his well-established impulses that can be so annoying elsewhere — the self-righteousness, the straw men, the great men, the men who aren’t onstage but are nevertheless digging deep in their diaphragms to deliver their lines to the back row — actually work. (It helps that there are almost no women here for Sorkin to mangle.) It’s about a trial, and it’s about activism, two worlds where people spend a lot of time trying to move hearts and minds with instances of grandstanding. The film moves between these innately theatrical spheres with a crackling energy, slipping easily from the courtroom in 1969 to the preparations and protests in 1968. What makes it so rousing is not the floridness of the dialogue but the way it’s used to acknowledge that moral clarity is not an end unto itself. While Assistant U.S. Attorney Richard Schultz (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), acting at the behest of the new Nixon administration, tries to create a monolithic bogeyman out of the “radical left,” we’re shown how little agreement there actually is on the side of the seven defendants as to what it means and how to effect change.

There’s so little agreement that there are actually eight defendants when the trial begins. Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) insists on his own representation, despite being forced to fend for himself after his lawyer has a medical emergency. It’s politically expedient for the prosecution to group Bobby in with the others in what they dub “the all-star team,” but he rejects the forced comparison — “Your life, it’s a fuck-you to your father, right? And you can see how that’s different from a rope on a tree?” he asks Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) midway through the movie, after Fred Hampton (Kelvin Harrison Jr.) is killed by the FBI. Tom and Rennie Davis (Alex Sharp) are part of Students for a Democratic Society, and their focus on stopping the war and winning elections doesn’t entirely jibe with the anti-authoritarian Yippies, as represented by Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong), who want a cultural revolution as well as a political one. Their readiness to hurl Molotov cocktails in turn contrasts with David Dellinger’s (John Carroll Lynch) committed pacifism. John Froines (Danny Flaherty) and Lee Weiner (Noah Robbins), more minor players who comment from the sidelines, muse that “this is the Academy Awards of protests, and as far as I’m concerned, it’s an honor just to be nominated.”

It’s a sprawling ensemble — capped by Mark Rylance and Ben Shenkman, as the group’s attorneys, William Kunstler and Leonard Weinglass, and Michael Keaton in a small but pivotal role — and Cohen and Strong emerge as the standouts. They sometimes feel like a stoner-comedy duo, with Strong doing a voice best described as Tommy Chong by way of Bullwinkle J. Moose. But Cohen emphasizes Abbie’s shrewdness, the intention behind all the jokey irreverence. The Trial of the Chicago 7 plays fast and loose with certain details; when Seale was infamously bound and gagged at the order of Judge Julius Hoffman (Frank Langella), who wears his biases openly, it was for days, not for the minutes shown in the movie before his trial is severed from the rest of the defendants’. But as an account of history as filtered through Sorkin’s sensibility, the film takes a thrillingly unexpected, if also understated, turn against civility. When Abbie and Tom have it out over who should be the one among them to take the stand, it’s Abbie whose point is the better one and Abbie who tells the courtroom, “I think the institutions of our democracy are wonderful things that right now are populated by terrible people.”

Sorkin will always romanticize the idea of the honorable conservative and the promise of polite bipartisanship that accompanies it. At the end of

a talk at the San Sebastián Film Festival earlier this week, he offered up his scenario for how he would script the end of Election Night, and it was more unbearable than anything The Newsroom had to offer: Trump refuses to concede, and “for the first time, his Republican enablers march up to the White House and say, ‘Donald, it’s time to go.’” It’s the reason that fantasy of the perfect speech is as nauseating as it is appealing: It’s one based around the idea that there’s a universal understanding of what is right and that everyone wants to act on behalf of it, once enlightened or appropriately shamed. From the first time Gordon-Levitt appears onscreen as Schultz, who is portrayed as an eager up-and-comer disturbed by some of the trial’s developments, it’s obvious that the movie won’t be able to resist giving us some sign that he’s not just a good soldier. It’s an eye-rolling moment but minor compared with the film’s underlying acknowledgement that this trial was about attempting to punish people for refusing to abide by rules and structures that are inherently unfair. The movie ends not with a speech but with a listing of names — a reminder that demands for respectability and good behavior can equal demands for silence, especially when the straightforward speaking of facts counts as rebellion.