The legacy of the collapse of Stalinism

December 2021 marks the thirtieth anniversary of the official dissolution of the USSR.

December 2021 marks the thirtieth anniversary of the official dissolution of the USSR. This year's Socialism event in November included a session on the legacy of the collapse of the Stalinist regimes in Russia and Eastern Europe, introduced by Clive Heemskerk, editor of Socialism Today, the Socialist Party's monthly magazine. Below is an edited transcript of his introduction.

This year's Socialism is taking place one month short of the day 30 years ago, on Christmas Day in 1991, that Mikhail Gorbachev announced the dissolution of the USSR - the 'Union of Soviet Socialist Republics' - which had been founded five years after the October revolution of 1917, in 1922.

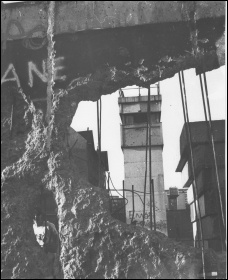

The end of the USSR did not have the same iconic imagery as the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 or the execution of the Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. But Gorbachev's announcement was the culmination of the collapse of the Stalinist regimes in Eastern Europe and the USSR, events which opened up a new era and gave a renewed impetus to capitalism for a whole historical period.

Firstly, it led to an ideological disarming of the workers' organisations - both the trade unions and their traditional political parties - consolidating the idea that there was no alternative possible to capitalism.

And secondly, it created a new world order - globalisation under rules set by the USA including the opening up of China - in which the countries of the ex-colonial world, both the masses and the elites within those countries, also no longer saw an alternative model of economic development.

But that 'post-Stalinist' era is ending, with the factors that gave capitalism a new lease of life turning into their opposite, opening up another new period - of the system showing once again its inability to solve the problems of society (economically, socially, and environmentally too); generating a new mass awareness of the need for a different way of organising human relations; and therefore creating the conditions for a mass revival of socialist ideas.

Those themes show that understanding the legacy of the collapse of Stalinism in Russia and Eastern Europe is not just an historical discussion, but sets the parameters for the events that will unfold in the years ahead.

Ideological defeat

There is an irony in discussing the legacy of the collapse of Stalinism at the Socialism weekend, because for us the totalitarian Stalinist regimes were not models of socialism but a grotesque caricature.

Leon Trotsky, whose ideas we base ourselves on, was actually the first Russian 'dissident' against Stalinism, defending the ideals of the 1917 October revolution which he led alongside Vladimir Lenin, against a regime headed by Joseph Stalin which emerged and then consolidated itself in power in the 1920s, before Trotsky was assassinated by an agent of Stalin in 1940.

Trotsky defended, as we do, the 1917 revolution as the greatest democratic movement in history, transferring power from the landlords, the factory owners, the judges, the elite civil servants, the police chiefs, the army tops, the owners and editors of the means of communication, the university directors, and so on, to committees of the people, of workers and peasants - the soviets - democratising every aspect of economic and social life.

But the revolution took place in a relatively underdeveloped country, mainly a peasant economy, with mass illiteracy, facing armed intervention from 21 different countries, including Britain, which sent troops to Archangel, Vladivostok, and the oilfields of Azerbaijan.

And because the revolution did not spread to the West - above all to the more economically advanced Germany where a series of revolutionary opportunities were lost from 1918 to 1923 - mass participation in the running of society was under constant pressure and increasingly replaced by the rule of the officialdom, the administrators, the bureaucracy as Trotsky termed it, which consolidated itself as a system of rule in the 1920s.

Initially, with the removal of the old owners, state direction of the economy still saw enormous economic progress made, even under the rule of the bureaucracy. There are many different figures but even the ideologically pro-capitalist Economist magazine, on the hundredth anniversary of the 1917 Russian revolution, pointed out that manufacturing output in the USSR grew by over 170% from 1928 to 1940 while "the rest of the world wallowed in the Depression". (11 November 2017)

But without the check of either workers' democracy or the price signals of the capitalist market, this came with enormous overheads. So, after a new spurt in the period following the end of world war two, the economy began to stagnate, unable to incorporate new technology, for example, or be flexible enough to meet new consumer needs, with the bureaucracy moving from being a relative fetter to an absolute fetter.

So what failed in the late 1980s and early 1990s was not democratic planning of the economy by the mass of the population - but the unchecked, top-down, bureaucratic planning of an unaccountable elite. Yet still the collapse of that system - not socialism but Stalinism - was used to 'prove' that socialism was unworkable and that the capitalist market was the only viable way of organising society.

It was an objective defeat, ideologically, for the international working class that led to a period of capitalist triumphalism - a torrent of propaganda about the 'end of history' - summed up in a headline in the Wall Street Journal, 'We Won'.

Impact on working-class organisation

The first consequence was the impact for a whole historical period on the confidence of even the most active, politically conscious workers in the possibility of socialism. This had its effect on working-class organisation in the 1990s - on the combativity of the trade unions and workers' parties - exemplified in Britain as the leader of an international trend with the transformation of Labour into Tony Blair's capitalist New Labour.

The Labour Party had been formed in 1900 as the result of the working class and its organisations coming into conflict with the capitalists and their political representatives in both the Conservative and Liberal parties, and drawing the conclusion of the need for their own independent party - which in turn developed their class consciousness by bringing workers together to discuss collectively their different sectional interests and their common struggle.

The party was a 'capitalist workers party', with a leadership which still reflected the outlook of the capitalist class but with a working-class base, and a structure through which the unions could move to challenge the leadership and threaten the capitalists' interests. This meant that, until Blair, Labour governments, while reluctantly tolerated as a means of holding the working class in check, were simultaneously undermined and eventually brought down by the capitalists when they could no longer accomplish that task.

That dual character of the party meant that when - in 1960 - the right-wing Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell tried to abolish the socialist Clause Four of Labour's constitution adopted in 1918 for "the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange", he was met with a storm of protest in the workers' organisations.

Even Harold Wilson, who went on to become prime minister in 1964, opposed the move, saying at the time that "nationalisation is to socialism what Genesis is to the Bible - it is the fundamental opener". While Michael Foot, who also later became Labour leader in 1980, said: "Like it or not, one of the most spectacular events of our age is the comparative success of the communist economic system".

Contrast that with 35 years later, in 1995 - just five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall - when Tony Blair was able to replace Clause Four with a new clause supporting the dynamic "enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition" with barely a whimper of opposition. And then back that up with organisational changes massively reducing the role of the unions within the Labour Party, to change its character into the completely capitalist dominated New Labour.

That process - of changing workers' parties into capitalist formations, which was an international trend - would not have been possible without the new conditions created by the collapse of Stalinism.

New world order

The collapse of Stalinism in Russia and Eastern Europe was an ideological defeat but it had material consequences in creating a new world balance of forces, no longer shaped by the 'clash of systems' that had defined the post-war period after 1945.

US imperialism had emerged from the rubble of world war two as the overwhelmingly dominant power among the capitalist nations. But the other victor was Russian Stalinism, with the war against Nazi Germany being effectively won on the Eastern front - there were 454,000 deaths suffered by Britain in World War Two, military and civilian, but at least 20 million by the USSR. The strengthened prestige of Russian Stalinism was especially dangerous for capitalism as a model in the former colonial countries, exploited and underdeveloped by the imperialist powers. But generally it presented a systemic challenge as a non-capitalist society.

The fear this generated was revealed in one incident, which only came to light after the release of government papers under the 30-years rule in 1991. In 1960, the Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev had gone to the UN and boasted that the USSR would 'catch up and surpass' the West. The then British prime minister Harold Macmillian sent a memo to the Foreign Office asking, "do you suppose this is true?" - to which the reply was 'Yes', maybe by 1980! This actually shows that they didn't understand the inherent contradictions of a planned economy without the check of workers' democracy, how the grip of the bureaucracy meant that it was doomed to stagnation.

But that fear explains the US intervention in Korea, in Vietnam, the propping up of the military in Pakistan, the attempt to overturn the Cuban revolution, and so on.

And it also explains the common interest that was created between the different national capitalist powers, a 'glue' to patch over their conflicting interests. Tensions certainly persisted between them throughout the cold-war period - erupting openly on occasions - but a lid was kept on them by the check made on world capitalism by the very existence of the non-capitalist, Stalinist, states.

It was this international order that ended with the collapse of Stalinism in Russia and Eastern Europe, leaving the US as the world 'hyperpower'.

The post-1945 international institutions were remoulded in the 1990s under US direction - GATT, set up in 1947, was re-launched as the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995, for example - and under presidents George HW Bush and then Bill Clinton a 'Washington Consensus' was inaugurated of unrestrained access for US capital to the world markets - 'globalisation' - so that 85% of the global capital stock (in real terms) of the world's multinational corporations has been generated after 1990.

This included the opening up of China, which was admitted to the WTO in 2010 - actually on stricter terms, on paper at least, than the ex-Stalinist states of Eastern Europe.

This was a period of 'capitalism unleashed' - of US capitalism in particular - backed up militarily: between 1989 and 2001 the US intervened abroad once every 16 months, more frequently than in any period in its history.

Things turn into their opposite

But things turn into their opposite. The era of 'unleashed capitalism' - with the ideological and organisational weakening of the check that workers' organisation imposes on the capitalists - saw an explosion of inequality.

The share of national income, including capital gains, going to the top 1% in the US has doubled since 1980 from 10% to 20% (while the share of the top 0.01%, 16,000 families, went from 1% to 5%), back to 19th century levels of inequality. But this was not just in the USA. In Britain wages' share of gross domestic product fell from a peak of 65% in 1976, to 53% in 2008.

However, the consequence of this shift in power to the capitalists over the working class was to weaken demand and deepen a fundamental contradiction of capitalism. As The Economist wrote in 2012, noting the irony, "a high share of GDP for profits results in a low share for wages and thus may eventually be self-limiting - a positively Marxist outcome".

And things turned into their opposite in world relations too. Without the 'glue' of the 'clash of systems' pushing the capitalist nation states together, inter-imperialist rivalries resurfaced and deepened.

There has been a 'block-isation' of the world economy, with no new global trade round completed for twenty years - there are now over 300 regional trade agreements compared to just 70 in 1990.

The US was, and still is, the greatest military power - accounting for 35% of global military spending. But there are new flashpoints, not least between the US and the rising world power of China - which has brought capitalist relations into its economy over the past 30 years but under the direction of the state, and which therefore continues to be officially classified by the WTO as a 'non-market economy', still not compliant with the 2010 entry terms.

And the Iraq war was a moment of 'imperial overreach' by the US, producing a global movement of opposition with possibly 30 million demonstrating in over 600 cities in February 2003 - which the New York Times said showed there "may still be two superpowers on the planet: the United States and world public opinion".

That movement was largely an elemental tide of protest - the 'potential superpower of the street' lacked organised form and clear political aims. It showed both that the effects of the collapse of Stalinism had still not been fully overcome, but also how they will be.

The 2007-08 financial crash was a further turning point in shifting mass consciousness, in undermining both the ideas and the institutions supporting the capitalists' control of society, and responsible for the revival of basic socialist ideas - as shown in the Corbyn waves, the support for the Bernie Sanders' US presidential campaigns, particularly in 2016, the initial Syriza victory in Greece in 2015, the rise in just a matter of years of Podemos in Spain, and so on.

Even if those movements didn't realise their potential this time because of the weakness of their programmes, they show that 'capitalism unleashed' will generate mass opposition that looks to 'socialism' - because socialism is not just an idea but the reflection of the common, collective interests of the working class.

Thirty years is a long time in the life of an individual but a brief moment in history. We still need to answer the fear that socialism will inevitably lead to dictatorship - the lasting baleful legacy of Stalinism - but the main point is that events are showing that the idea of socialism can again become a mass force, a 'fresh idea' for millions.

And that the new era that is opening up will create the objective conditions once again for Marxists to boldly intervene - as we have done before in our history, as in Liverpool or the great anti-poll tax non-payment campaign - and begin a movement that could challenge the capitalist system itself and adopt a full programme for the socialist transformation of society.

Why is socialism in one country impossible?

Why did Russia degenerate into a totalitarian, Stalinist dictatorship, and how does the planned economy work to develop the productive forces without the “check” of the market?

What about Mao and the Chinese Revolution?

Is China today communist or capitalist?

Q. Why is socialism in one country impossible?

A. First of all, socialism absolutely needs to be based on a high level of productivity. The lowest stage of socialism must be the highest stage of capitalism. If so many of the problems in the world today are due to the unequal distribution of resources, then the only solution is to produce more than enough and distribute it democratically to provide a high standard of living for all. Nowhere in any of the writings of Marx, Engels, Lenin, or Trotsky will you find them proposing the idea of socialism in one country. The Stalinist, nationalist idea of socialism in one country has nothing to do with Marxism which has always been internationalist in perspective.

The working class has had many opportunities to carry out a socialist transformation over the last century, and has tried in many different countries. However only once, and then only temporarily did they succeed, in the Russian Revolution of 1917. This revolution in a backward country succeeded in overthrowing 1000 years of Tsarist autocracy, and the working class began to grapple with running the whole of society. However it was never the intention of Lenin to build socialism in one country. That is impossible, as socialism requires a massive increase in production to produce the needs of society. That requires the pooling of resources internationally. Also of course, capitalism cannot simply be defeated in a single country. The revolution must spread to other countries, and eventually the whole world.

As a result of its isolation, and its backwardness, civil war, and the assault of 21 armies of foreign intervention, the revolution in Russia hung by a thread. Without the assistance of revolutions in more economically advanced countries in Europe, there could not be socialism in Russia. If the revolutions in the rest of Europe had been successful, they could have all pooled their technology, natural resources, and populations as one in order to begin producing enough for all and spreading the revolution to the rest of the world. Instead, the isolated revolution degenerated into a bureaucratic dictatorship. The struggle for socialism must be international!

Return to Stalinism menu

Return to Marxism FAQ menu

Q. Why did Russia degenerate into a totalitarian, Stalinist dictatorship, and how does the planned economy work to develop the productive forces without the “check” of the market?

A. In order to be able to understand the process of the socialist transformation of society, and why it has not yet succeeded, we must be able to give a scientific answer to the question what happened to the USSR? There is an entire book online about this question, called Russia: from Revolution to Counter-Revolution. But a brief generalization of the events is as follows.

First of all, the general historic appraisal that we make of the Russian Revolution is extremely positive. For the first time, the mass of workers and peasants proved in practice that it was possible to run society without landlords, capitalists, and bankers. The superiority of a planned economy over the anarchy of capitalist production was proved, not in the field of ideas but on the concrete arena of industrial development, raising living standards, education, and health. Russia, in a short period of time, went from being a backward, mainly agricultural, and imperialist dominated country into being one of the first industrial and economic powers on earth. And this was achieved only because of the planned economy. If you take any other backward capitalist country of that time and you see its evolution over the last 80 years, with very few exceptions, you will see that it remains backward and dominated by imperialism. You can use as examples India, Pakistan, the Philippines, most of Latin America, etc.

But at the same time we must be able to explain why the Stalinist states with their potentially very productive planned economies then entered into crisis at the end of the 1980s and eventually collapsed in the early 1990s. We think that the explanation lies in the lack of democratic control over the planning of the economy. Under capitalism, the market represents, to a certain extent, a check on the economy. If you own a shoe making factory, and the shoes you produce are of very poor quality and more expensive than others in the market, you will probably go bankrupt. If you invest in a sector of the economy where there is already overproduction you will probably go bankrupt.

So the market, although in an anarchic way and through devastating cyclical crises, represents a certain check on the productive forces (although this has been diminished by the concentration of the economy in the hands of a few multinational corporations). That does not exist under a planned economy. The only possible control is that of the democratic participation of working people (consumers and producers themselves) in the planning of the economy. Who knows better than the workers themselves the needs that there are in their neighborhoods? Who better than them knows how the factories should be organized? The problem in the Soviet Union was that these democratic controls did not exist at all. A handful of bureaucrats at the top of the “Communist Party” and the state apparatus dictated everything. .

It is clear that an economy which produced one million different commodities every year could not be controlled without real genuine workers’ democracy. So, why was there no workers’ democracy in the USSR? The bourgeois critics will tell us that this was the inevitable consequence of the struggle for socialism. “Communism is anti-democratic and means dictatorship.” We reply: these are all lies and slanders.

If you read Lenin’s State and Revolution, you can see how Lenin establishes a series of conditions for the functioning of workers’ democracy, which he draws mainly from the experience of the 1871 Paris Commune, the first workers’ government in history. There are four main conditions:

1) All public officials to be elected and with the right to recall (that is that they can be changed immediately when they longer represent the interests of those who elected them).

2) No public official to receive a wage higher than that of a skilled worker. Marx said that “social being determines consciousness,” in other words the way you live determine the way you think. One of the main causes for reformism amongst labor movement leaders is precisely the inflated salaries they receive as members of the government, or even trade union top officials. They therefore think that capitalism is “not so bad” after all.

3) No standing army, but general arming of the people.

4) Over a period of time everyone would participate in the tasks of running the economy and the state. In the words of Lenin “if everyone is a bureaucrat, no one is a bureaucrat.”

Even a superficial analysis of these conditions will immediately lead us to the conclusion that none of them applied in the old Soviet Union. But why? In the first years of the revolution, Lenin and the other leaders of the revolution struggled to establish what was probably the most democratic regime which has ever existed. The soviets (workers’ and peasants’ councils) were running the state and the economy and everyone was allowed to participate in them. All political parties were allowed to participate in soviet elections and debates and put forward their ideas. It is a little known fact that the first Soviet government was in fact a coalition between the Bolshevik Party and the left wing Social Revolutionaries. The only parties not allowed were those which had taken up arms against Soviet power.

Within the Communist Party (as the Bolsheviks were later called) there was the widest of democracies. During the discussion of the Brest-Litovsk peace agreement with Germany there were at least three different fractions within the CP with different opinions. One of them, the Left Communists, headed by Bukharin, even published for a while a daily paper, The Communist, opposing Lenin’s position on the issue! So, how could such a democratic regime become a dictatorship?

Lenin, in State and Revolution also deals with the questions of the economic preconditions for the establishment of socialism. The democratic planning of the economy can only be established if you have the economic and material basis to produce plenty for all. As soon as there is scarcity of the basic goods, inevitably, there must be someone to control in an authoritarian way, the distribution of these scarce goods. In short, in Russia in 1917 the material conditions for socialism did not exist.

So why did the Bolsheviks organize the revolution in Russia? Their perspective was never building socialism in Russia in isolation. They saw the Russian Revolution as the beginning of the European revolution. They thought that the taking of power by the workers in Russia would lead to a wave of revolutionary struggle all over Europe. Workers’ power in Europe would provide the material means for a fast development of backward Russia. And in fact, the Russian Revolution opened the way for a massive revolutionary wave in Europe. There was the 1918–19 German revolution, the Hungarian Soviet Republic, the Spanish revolutionary general strike, factory occupations in Italy, and in general mass movements of the working class all over the continent. But unfortunately, all these revolutions were defeated.

The were various reasons for these defeats, but to summarize it, the labor movement was still very much under the influence of the social democratic reformist leaders, and the Communists had not had time to organize properly and made a number of fatal mistakes in this period. So, in this way, the Russian Revolution became isolated in a backward, mainly peasant country, ruined by the First World War. If that was not enough, immediately they were sucked into a vicious civil war, in which the counterrevolution with the support of 21 foreign armies of intervention tried to overthrow the young soviet republic (and they nearly succeeded).

Finally, the Red Army won the civil war but at a very high cost. Not only the economy was completely destroyed and the masses were starving, but also the cream of the cream of revolutionary communist cadres had been killed over these difficult years. One of the preconditions for workers’ democracy is precisely a general shortening of the working week, in order to allow all working people time enough to raise their level of education and to participate in politics and the running of society. In Russia we actually had a longer working week and very bad conditions in general. Participation in the soviets slowly dropped and a layer of officials started to emerge which slowly started to push the normal workers out of politics and discourage participation.

One of the first to warn against the danger of bureaucratization was actually Lenin in his last writings, which were suppressed by Stalin for many years. But even under these extremely difficult conditions it was not easy for the Stalinist bureaucracy to firmly establish a grip on power. There was a very big opposition in the ranks and the leadership of the Communist Party. In fact, the bureaucracy had to physically eliminate most of the party in order to succeed. If you take the Central Committee of the party in 1917, the revolutionary leaders who carried out the October Revolution, by 1940 there was only one survivor apart from Stalin. Most of the others had been shot dead by Stalin, died in prisons and labor camps, some were missing and a few had died of old age. Thousands of honest and loyal Communists were killed or died in the concentration camps. The person who waged the most comprehensive opposition against the rise of bureaucracy was Trotsky, who with Lenin had led the October Revolution and later organized the Red army.

The figure of Trotsky has been obscured for many years in the Communist movement, precisely by those who defended unconditionally the Stalinist bureaucracy. That is why it is to be welcomed for example that the documents of the last Congress of the South African Communist Party (ex-Stalinists) recommend the reading of his writings. Communists can only learn from an open and frank debate about the reasons for the rise of Stalinism. See also Lenin and Trotsky: What They Really Stood For.

Return to Stalinism menu

Return to Marxism FAQ menu

Q. What about Mao and the Chinese Revolution?

A. From time to time it is necessary to draw a balance sheet of our ideas and theoretical positions. How did they work out in practice over the past fifty years? If there is a major contribution of our tendency to Marxism, this is our analysis of the colonial revolution and the development of proletarian bonapartism, beginning with our analysis of the Chinese revolution after 1945. It was precisely the impasse of capitalism in these countries and the pressing need of the masses for a way forward which gave rise to the phenomena of proletarian bonapartism. This was due to a number of different factors. In the first place, the complete impasse of society in the backward countries and the inability of the colonial bourgeoisie to show a way forward. Secondly, the inability of imperialism to maintain its control by the old means of direct military-bureaucratic rule. Thirdly, the delay of the proletarian revolution in the advanced capitalist countries and the weakness of the subjective factor. And lastly, the existence of a powerful regime of proletarian bonapartism in the Soviet Union.

The victory of the USSR in the Second World War, and the strengthening of Stalinism after the war with its extension to Eastern Europe and the victory of the Chinese Revolution were all factors that combined to condition the development of proletarian bonapartism as a peculiar variant of the permanent revolution which was only understood by our tendency. This was an entirely unprecedented and unexpected phenomenon. Nowhere in the classics of Marxism was it even considered as a theoretical possibility that a peasant war could lead to the establishment of even a deformed workers’ state. Yet this is precisely what occurred in China, and later in Cuba and Vietnam.

We characterized the Chinese revolution as the second greatest event in world history, after the Russian revolution of 1917. It had an enormous effect in the subsequent development of the colonial revolution. But this revolution did not take place on the classical lines of the Russian Revolution in 1917 or the Chinese Revolution of 1925–27. The working class played no important role. Mao came to power on the basis of a mighty peasant war, in the traditions of China. The only way Mao was able to win the civil war of 1944–49 was by offering a program of social liberation to the peasant armies of Chiang Kai-shek, who was armed and backed by American imperialism. But the Stalinist leaders of the peasant Red Army had no perspective of leading the workers to power as did Lenin and Trotsky in 1917. When Mao’s peasant armies arrived at the cities, and the workers spontaneously occupied the factories and greeted Mao’s armies with red flags, Mao gave the order that these demonstrations should be suppressed and the workers were shot.

Initially, Mao did not intend to expropriate the Chinese capitalists. His perspectives for the Chinese revolution were outlined in a pamphlet called New Democracy in which he wrote that the socialist revolution was not on the order of the day in China, and that the only development that could take place was a mixed economy, i.e., capitalism. This was the classical “two stage” Menshevik theory which had been adopted by the Stalinist bureaucracy and had led to the defeat of the Chinese revolution in 1925–27. But our tendency understood that under the concrete conditions that had developed that Mao would be forced to expropriate capitalism.

Not only that but we also predicted in advance the fact that Mao would be forced to break with Stalin. Already in early 1949 we wrote:

“The fact that Mao has a genuine mass base independent of the Russian Red Army, will in all likelihood provide for the first time an independent base for Chinese Stalinism which will no longer rest directly on Moscow. As with Tito, so with Mao, despite the role of the Red Army in Manchuria, Chinese Stalinism is developing an independent base. Because of the national aspirations of the Chinese masses, the traditional struggle against foreign domination, the economic needs of the country and above all, the powerful base in an independent state apparatus, the danger of a new and really formidable Tito in China is a factor which is causing anxiety in Moscow.”

However, the subordination of the Chinese economy to the benefit of the Russian bureaucracy, with the attempts to place puppets in control who will be completely subordinate to Moscow—in other words, the national oppression of the Chinese—will create the basis for a clash with the Kremlin of great magnitude and significance. Mao, with an independent and powerful state apparatus, with the possibility of maneuvering with the imperialists of the West (who will seek to negotiate with China for trade and try and drive a wedge between Peking and Moscow) and with the support of the Chinese masses as the victorious leader against the Kuomintang, will have powerful points of support against Moscow.

Stalin’s very efforts to try and forestall this development will tend to accelerate and intensify the resentment and the conflict. (“Reply to David James”, reprinted in, The Unbroken Thread, 304.)

These lines were written more than a decade before the outbreak of the Sino-Soviet conflict, when the Chinese and Russian bureaucracies seemed to be inseparable allies.

The victory of Mao’s peasant armies in China was due to a number of factors: the complete and utter impasse of Chinese capitalism and landlordism, the inability of imperialism to intervene because of the war-weariness of the imperialist troops after the Second World War, and also because of the colossal power of attraction of the nationalized planned economy in Stalinist Russia which demonstrated its superiority during the war with Hitler’s Germany.

The fact that the peasantry was used to carry through a social revolution was a completely new development in the history of China. China was the classical country of peasant wars, which took place at regular intervals. But even when these wars were victorious this merely resulted in the fusion of the leading elements of the peasant armies with the elite in the towns, resulting in the formation of a new dynasty. It was a vicious circle which characterized Chinese history for over 2,000 years. But here we had a fundamental departure. The peasant army under Mao was able to smash capitalism and create a society on the image of Stalin’s Moscow. Of course, there could be no question of a healthy workers’ state as in Russia in November 1917 being established by such means. For that, the active participation and leadership of the working class would be required. But a peasant army, without the leadership of the working class, is the classical instrument of Bonapartism, not workers’ power. The Chinese Revolution of 1949 began where the Russian Revolution had ended. There was no question of soviets or workers’ democracy. From the very beginning it was a monstrously deformed workers’ state. Our tendency underlined that on the world scale the only class which can bring about the triumph of socialism is the proletariat.

Once Mao had taken power and created a state apparatus on the basis of the hierarchy of the Red Army he did not have any need to ally himself with the bourgeoisie. In a typical bonapartist fashion, Mao balanced between the different classes. He leaned on the peasantry and to a certain extent on the working class to expropriate the capitalists, but once these had been defeated he then proceeded to eliminate any elements of workers democracy that might have existed. This phenomena was possible precisely because of the delay of the world revolution and the impasse of society. He had the powerful example of Stalinism in Russia, where a strong bureaucracy was parasitizing the planned economy and benefiting from it, so he decided to follow the same model. Despite its monstrously deformed character, the Chinese Revolution nevertheless represented a gigantic step forward for hundreds of millions of people who had been the beasts of burden of imperialism.

Return to Stalinism menu

Return to Marxism FAQ menu

Is China today communist or capitalist?

The Chinese bureaucracy, having seen the collapse of Stalinism in the USSR and Eastern Europe, sought a way to invigorate their economy and maintain their privileged positions. Beginning in 1978, Deng Xiao Ping introduced a series of measures to invigorate the economy to stimulate the economy. Since this time it has taken on a life of it’s own. Throughout the 1980s “free market zones” were established, allowing foreign-owned companies to operate with Chinese labor. Along with this process was a decline in the conditions of the Chinese working class. This is what lead to the massive Tianenmen Square movement which threatened to overthrow the bureaucracy. During the 1990s the bureaucracy accelerated the process, with more state enterprises being reorganized to be geared towards private sector, if not completely nationalized. In 2001 China joined the World Trade Organization.

While it is impossible to say where the nationalized, planned economy passed qualitatively into capitalism, it is undeniable that what exists in China today is the worst features of capitalist exploitation, along with a monstrous Bonapartist state that visciously represses the working class.

The task of the Chinese working class, is not merely a political revolution to overthrow the bureaucracy—as was advocated by Marxists in regard to the Soviet Union—but a social revolution to overthrow the current regime and to take over the private industries, nationalize them, and put them under democratic, workers control.

For more on this process, please read our document China’s Long March to Capitalism

Return to Stalinism menu

Return to Marxism FAQ menu