Christopher Flavelle, The New York Times•January 21, 2020

Billy Ezzell takes down boards covering windows after Hurricane Florence in Carolina Beach, N.C., Sept. 17, 2018. (Eric Thayer/The New York Times)

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration is about to distribute billions of dollars to coastal states mainly in the South to help steel them against natural disasters worsened by climate change.

But states that qualify must first explain why they need the money. That has triggered linguistic acrobatics as some conservative states submit lengthy, detailed proposals on how they will use the money, while mostly not mentioning climate change.

A 306-page draft proposal from Texas doesn’t use the terms “climate change” or “global warming,” nor does South Carolina’s proposal. Instead, Texas refers to “changing coastal conditions” and South Carolina talks about the “destabilizing effects and unpredictability” of being hit by three major storms in four years, while being barely missed by three other hurricanes.

Louisiana, a state taking some of the most aggressive steps in the nation to prepare for climate change, does include the phrase “climate change” in its proposal in one place, an appendix on the final page.

The federal funding program, devised after the devastating hurricanes and wildfires of 2017, reflects the complicated politics of global warming in the United States, even as the toll of that warming has become difficult to ignore. While officials from both political parties are increasingly forced to confront the effects of climate change, including worsening floods, more powerful storms and greater economic damage, many remain reluctant to talk about the cause.

The $16 billion program, created by Congress and overseen by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, is meant to help states better prepare for future natural disasters. It is the first time such funds have been used to prepare for disasters like these that haven’t yet happened, rather than responding to or repairing damage that has already occurred.

The money is distributed according to a formula benefiting states most affected by disasters in 2015, 2016 and 2017. That formula favors Republican-leaning states along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, which were hit particularly hard during that period.

Texas is in line for more than $4 billion, the most of any state. The next largest sums go to Louisiana ($1.2 billion), Florida ($633 million), North Carolina ($168 million) and South Carolina ($158 million), all of which voted Republican in the 2016 presidential election.

The other states getting funding are West Virginia, Missouri, Georgia and California, the only state getting money that voted Democratic in the presidential race of 2016. California hasn’t yet submitted its proposal, but in the past the state has spoken forcefully about the threat of climate change, in addition to fighting with the Trump administration to limit greenhouse gas emissions from cars.

Half the money, $8.3 billion, was set aside for Puerto Rico, as well as $774 million for the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Trump administration has delayed that funding, citing concerns over corruption and fiscal management.

Not every state has felt compelled to tiptoe around climate change. Florida’s proposal calls it “a key overarching challenge,” while North Carolina pledges to anticipate “how a changing climate, extreme events, ecological degradation and their cascading effects” will affect state residents.

The housing department has itself been careful about how it described the program’s goals. When HUD in August released the rules governing the money, it didn’t use the terms “climate change” and “global warming” but referred to “changing environmental conditions.”

Still, the rule required states that received money to describe their “current and future risks.” And when those risks included flooding — the most costly type of disaster nationwide — states were instructed to account for “continued sea level rise,” which is one consequence of global warming.

A spokeswoman for the housing department did not respond to requests for comment.

Stan Gimont, who as deputy assistant secretary for grant programs at HUD was responsible for the program until he left the department last summer, said the decision not to cite climate change was “a case of picking your battles.”

“When you go out and talk to local officials, there are some who will very actively discuss climate change and sea-level rise, and then there are those who will not,” Gimont said. “You’ve got to work with both ends of the spectrum. And I think in a lot of ways it’s best to draw a middle road on these things.”

Texas released a draft version of its plan in November. That draft said the state faced “changing coastal conditions,” as well as a future in which both wildfires and extreme heat were expected to increase. In response, the state proposes better flood control, buying and demolishing homes in high-risk areas and giving counties money for their own projects.

But state officials in Texas, where Republicans control the governor’s mansion and both chambers of the Legislature, were silent on what is causing the changes. The report does not cite climate change or global warming, though “climate change” pops up in footnotes citing articles and papers with that phrase in their titles.

Brittany Eck, a spokeswoman for the Texas General Land Office, which produced the proposal, did not respond to questions about the choice of language or the role of climate change in making disasters worse. In an email, she said Texas would distribute the funding based on “accepted scientific research, evidence and historical data to determine projects that provide the greatest value to benefit ratio to protect affected communities from future events.”

Some local politicians in hard-hit areas of Texas are outspoken. Lina Hidalgo, a Democrat and the top elected official in Harris County, which includes Houston and which suffered some of the worst effects of Hurricane Harvey in 2017, said that addressing the effects of climate change was a top issue for her constituents.

“Harris County is Exhibit A for how the climate crisis is impacting the daily lives of residents in Texas,” Hidalgo said in a statement. “If we’re serious about breaking the cycle of flooding and recovery we have to shift the paradigm on how we do things, and that means putting science above politics.”

In South Carolina, which like Texas is controlled by Republicans in both legislative chambers and the governor’s office, the state’s proposal likewise makes no mention of climate change. It cites sea-level rise once, and only to say that it won’t be addressed.

The state’s flood-reduction efforts “will only address riverine and surface flooding, not storm surge or sea-level rise issues,” according to its proposal.

That is despite the fact that sea levels and storm surges are increasing across the coastal southeastern United States because of climate change, federal scientists wrote in a sweeping 2018 report. The report’s authors noted that Charleston, South Carolina, broke its record for flooding in 2016, at 50 days, and that “this increase in high-tide flooding is directly tied to sea-level rise.”

Megan Moore, a spokeswoman for South Carolina’s Department of Administration, said by email that the proposal “is designed to increase resilience to and reduce or eliminate long-term risk of loss of life or property based on the repetitive losses sustained in this state.” She did not respond to questions about why the proposal did not address climate change.

One of the states acknowledged that weather conditions were changing and seas were rising, but still mostly avoided the term climate change. Louisiana, whose location at the mouth of the Mississippi River makes it one of the states most threatened by climate change, intends to use the $1.2 billion it will receive to better map and prepare for future flooding — a major peril for countless low-lying areas — said Pat Forbes, executive director of the state’s Office of Community Development, which is managing the money.

“We realize we’ve got to get better, because it’s going to get worse,” Forbes said.

The state, where both the House and Senate are controlled by Republicans but the governor is a Democrat, submitted a proposal that makes references to climate change, noting that the risks of flooding “will continue to escalate in a warming world.”

Still, the 91-page report uses the phrase “climate change” only once, at the end of an appendix on its final page.

Forbes called climate change “not that important a thing for an action plan,” and said that mostly leaving the phrase out of the document was not intentional. He said the purpose of the proposal was to demonstrate to the federal government that Louisiana knows what it wants to do with the money.

“Our governor has acknowledged on multiple occasions that we expect the flooding to be more frequent and worse in the future, not better,” Forbes said. “So we’ve got to have an adaptive process here that constantly makes us safer.”

Other states used their proposals to emphasize the centrality of climate change to the risks they face. “Climate change is a key overarching challenge which threatens to compound the extent and effects of hazards,” wrote officials in Florida, where Republicans control both legislative chambers and the governor’s office.

In North Carolina, which has a Democratic governor and a Republican-controlled Legislature, the proposal argued that the state was trying to anticipate “how a changing climate, extreme events, ecological degradation and their cascading effects will impact the needs of North Carolina’s vulnerable populations.”

Shana Udvardy, a climate resilience analyst with the Union of Concerned Scientists, said the failure to confront global warming made it more important for governments to at least call the problem by its name.

“We really need every single state, local and federal official to speak clearly,” Udvardy said. “The polls indicate that the majority of Americans understand that climate change is happening here and now.”

Others were more sympathetic. Marion McFadden, who preceded Gimont as head of disaster-recovery grants at HUD during the Obama administration, said the department was responding to the political realities in conservative states. She described the $16 billion grant program as “all about climate change,” but said some states would sooner refuse the money than admit that global warming is real.

“HUD is requiring them to be explicit about everything other than the concept that climate change is responsible,” said McFadden, who is now senior vice president for public policy at Enterprise Community Partners, which worked with states to meet the program’s requirements. Insistence on saying the words raises the risk “that they may walk away.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2020 The New York Times Company

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration is about to distribute billions of dollars to coastal states mainly in the South to help steel them against natural disasters worsened by climate change.

But states that qualify must first explain why they need the money. That has triggered linguistic acrobatics as some conservative states submit lengthy, detailed proposals on how they will use the money, while mostly not mentioning climate change.

A 306-page draft proposal from Texas doesn’t use the terms “climate change” or “global warming,” nor does South Carolina’s proposal. Instead, Texas refers to “changing coastal conditions” and South Carolina talks about the “destabilizing effects and unpredictability” of being hit by three major storms in four years, while being barely missed by three other hurricanes.

Louisiana, a state taking some of the most aggressive steps in the nation to prepare for climate change, does include the phrase “climate change” in its proposal in one place, an appendix on the final page.

The federal funding program, devised after the devastating hurricanes and wildfires of 2017, reflects the complicated politics of global warming in the United States, even as the toll of that warming has become difficult to ignore. While officials from both political parties are increasingly forced to confront the effects of climate change, including worsening floods, more powerful storms and greater economic damage, many remain reluctant to talk about the cause.

The $16 billion program, created by Congress and overseen by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, is meant to help states better prepare for future natural disasters. It is the first time such funds have been used to prepare for disasters like these that haven’t yet happened, rather than responding to or repairing damage that has already occurred.

The money is distributed according to a formula benefiting states most affected by disasters in 2015, 2016 and 2017. That formula favors Republican-leaning states along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, which were hit particularly hard during that period.

Texas is in line for more than $4 billion, the most of any state. The next largest sums go to Louisiana ($1.2 billion), Florida ($633 million), North Carolina ($168 million) and South Carolina ($158 million), all of which voted Republican in the 2016 presidential election.

The other states getting funding are West Virginia, Missouri, Georgia and California, the only state getting money that voted Democratic in the presidential race of 2016. California hasn’t yet submitted its proposal, but in the past the state has spoken forcefully about the threat of climate change, in addition to fighting with the Trump administration to limit greenhouse gas emissions from cars.

Half the money, $8.3 billion, was set aside for Puerto Rico, as well as $774 million for the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Trump administration has delayed that funding, citing concerns over corruption and fiscal management.

Not every state has felt compelled to tiptoe around climate change. Florida’s proposal calls it “a key overarching challenge,” while North Carolina pledges to anticipate “how a changing climate, extreme events, ecological degradation and their cascading effects” will affect state residents.

The housing department has itself been careful about how it described the program’s goals. When HUD in August released the rules governing the money, it didn’t use the terms “climate change” and “global warming” but referred to “changing environmental conditions.”

Still, the rule required states that received money to describe their “current and future risks.” And when those risks included flooding — the most costly type of disaster nationwide — states were instructed to account for “continued sea level rise,” which is one consequence of global warming.

A spokeswoman for the housing department did not respond to requests for comment.

Stan Gimont, who as deputy assistant secretary for grant programs at HUD was responsible for the program until he left the department last summer, said the decision not to cite climate change was “a case of picking your battles.”

“When you go out and talk to local officials, there are some who will very actively discuss climate change and sea-level rise, and then there are those who will not,” Gimont said. “You’ve got to work with both ends of the spectrum. And I think in a lot of ways it’s best to draw a middle road on these things.”

Texas released a draft version of its plan in November. That draft said the state faced “changing coastal conditions,” as well as a future in which both wildfires and extreme heat were expected to increase. In response, the state proposes better flood control, buying and demolishing homes in high-risk areas and giving counties money for their own projects.

But state officials in Texas, where Republicans control the governor’s mansion and both chambers of the Legislature, were silent on what is causing the changes. The report does not cite climate change or global warming, though “climate change” pops up in footnotes citing articles and papers with that phrase in their titles.

Brittany Eck, a spokeswoman for the Texas General Land Office, which produced the proposal, did not respond to questions about the choice of language or the role of climate change in making disasters worse. In an email, she said Texas would distribute the funding based on “accepted scientific research, evidence and historical data to determine projects that provide the greatest value to benefit ratio to protect affected communities from future events.”

Some local politicians in hard-hit areas of Texas are outspoken. Lina Hidalgo, a Democrat and the top elected official in Harris County, which includes Houston and which suffered some of the worst effects of Hurricane Harvey in 2017, said that addressing the effects of climate change was a top issue for her constituents.

“Harris County is Exhibit A for how the climate crisis is impacting the daily lives of residents in Texas,” Hidalgo said in a statement. “If we’re serious about breaking the cycle of flooding and recovery we have to shift the paradigm on how we do things, and that means putting science above politics.”

In South Carolina, which like Texas is controlled by Republicans in both legislative chambers and the governor’s office, the state’s proposal likewise makes no mention of climate change. It cites sea-level rise once, and only to say that it won’t be addressed.

The state’s flood-reduction efforts “will only address riverine and surface flooding, not storm surge or sea-level rise issues,” according to its proposal.

That is despite the fact that sea levels and storm surges are increasing across the coastal southeastern United States because of climate change, federal scientists wrote in a sweeping 2018 report. The report’s authors noted that Charleston, South Carolina, broke its record for flooding in 2016, at 50 days, and that “this increase in high-tide flooding is directly tied to sea-level rise.”

Megan Moore, a spokeswoman for South Carolina’s Department of Administration, said by email that the proposal “is designed to increase resilience to and reduce or eliminate long-term risk of loss of life or property based on the repetitive losses sustained in this state.” She did not respond to questions about why the proposal did not address climate change.

One of the states acknowledged that weather conditions were changing and seas were rising, but still mostly avoided the term climate change. Louisiana, whose location at the mouth of the Mississippi River makes it one of the states most threatened by climate change, intends to use the $1.2 billion it will receive to better map and prepare for future flooding — a major peril for countless low-lying areas — said Pat Forbes, executive director of the state’s Office of Community Development, which is managing the money.

“We realize we’ve got to get better, because it’s going to get worse,” Forbes said.

The state, where both the House and Senate are controlled by Republicans but the governor is a Democrat, submitted a proposal that makes references to climate change, noting that the risks of flooding “will continue to escalate in a warming world.”

Still, the 91-page report uses the phrase “climate change” only once, at the end of an appendix on its final page.

Forbes called climate change “not that important a thing for an action plan,” and said that mostly leaving the phrase out of the document was not intentional. He said the purpose of the proposal was to demonstrate to the federal government that Louisiana knows what it wants to do with the money.

“Our governor has acknowledged on multiple occasions that we expect the flooding to be more frequent and worse in the future, not better,” Forbes said. “So we’ve got to have an adaptive process here that constantly makes us safer.”

Other states used their proposals to emphasize the centrality of climate change to the risks they face. “Climate change is a key overarching challenge which threatens to compound the extent and effects of hazards,” wrote officials in Florida, where Republicans control both legislative chambers and the governor’s office.

In North Carolina, which has a Democratic governor and a Republican-controlled Legislature, the proposal argued that the state was trying to anticipate “how a changing climate, extreme events, ecological degradation and their cascading effects will impact the needs of North Carolina’s vulnerable populations.”

Shana Udvardy, a climate resilience analyst with the Union of Concerned Scientists, said the failure to confront global warming made it more important for governments to at least call the problem by its name.

“We really need every single state, local and federal official to speak clearly,” Udvardy said. “The polls indicate that the majority of Americans understand that climate change is happening here and now.”

Others were more sympathetic. Marion McFadden, who preceded Gimont as head of disaster-recovery grants at HUD during the Obama administration, said the department was responding to the political realities in conservative states. She described the $16 billion grant program as “all about climate change,” but said some states would sooner refuse the money than admit that global warming is real.

“HUD is requiring them to be explicit about everything other than the concept that climate change is responsible,” said McFadden, who is now senior vice president for public policy at Enterprise Community Partners, which worked with states to meet the program’s requirements. Insistence on saying the words raises the risk “that they may walk away.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2020 The New York Times Company

KEEP THEM RELIGIOUS KEEP THEM IGNORANT

LOW EDUCATION INCREASED ANTI SCIENCE DEMAGOGUERY AND CLIMATE CHANGE DENIAL

IN THE POOREST WHITE RIGHT WING STATES

OF THE OLD SLAVE CONFEDERACY

LOW EDUCATION INCREASED ANTI SCIENCE DEMAGOGUERY AND CLIMATE CHANGE DENIAL

IN THE POOREST WHITE RIGHT WING STATES

OF THE OLD SLAVE CONFEDERACY

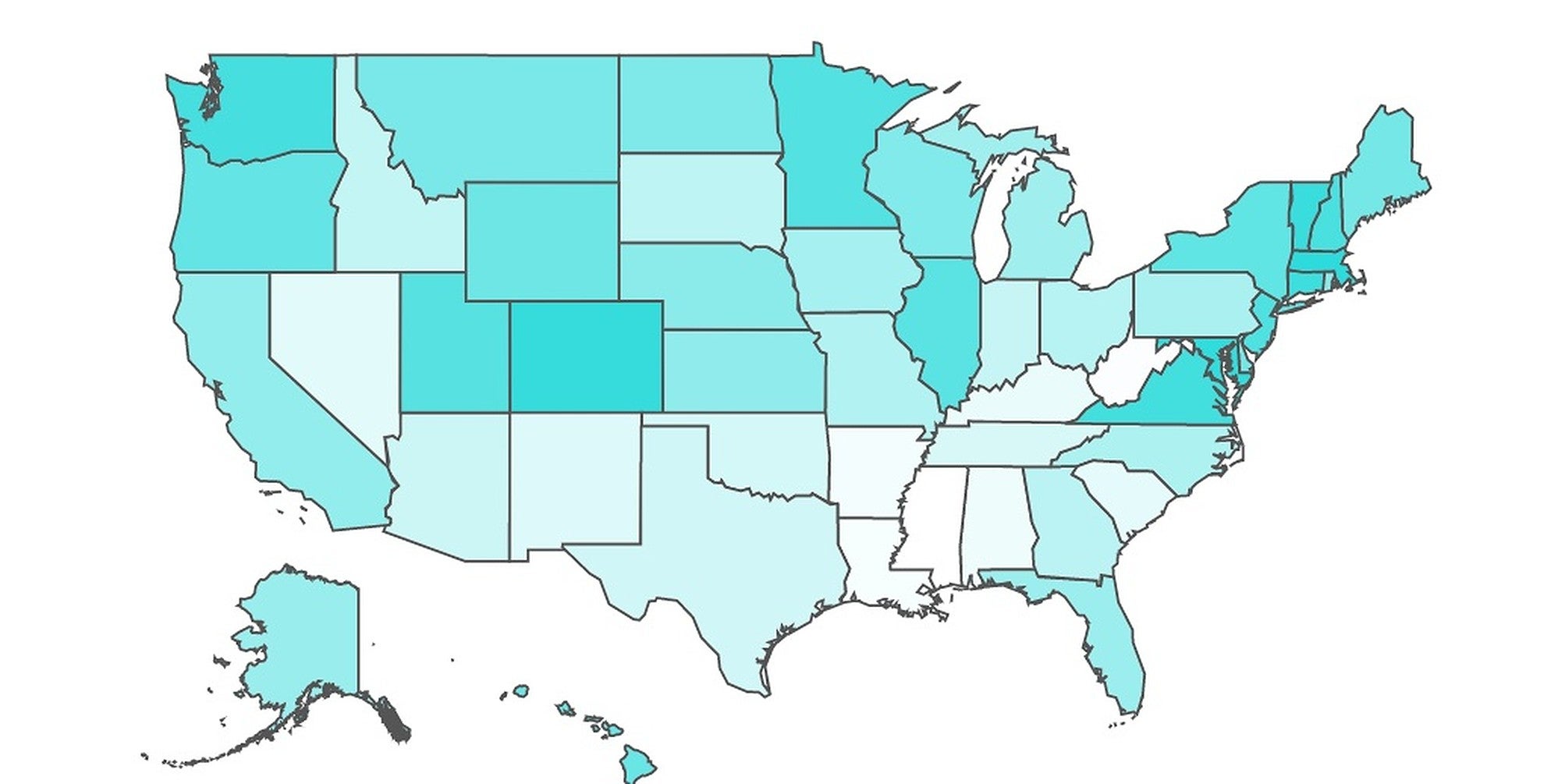

The most educated states in America, mapped

Image: WalletHub

For many people, an expensive education can be the ticket to better career opportunities and higher pay – but it isn’t attainable for all.

Website WalletHub have compiled a set of handy maps and charts that show how educated different states in America are.

Their methodology was pretty intensive, examining what they call “key factors” of a well-educated population: educational attainment, school quality, and achievement gaps between genders and races. Comparing all 50 states, the data set ranges across adults aged 25 and older with at least a high school diploma.

In order to determine the “most” and “least” educated states, they compared them across two key dimensions: educational attainment and quality of education, examined using 18 relevant metrics on a 100-point scale.

It’s pretty complex, and their findings were fascinating. WalletHub found that the top five states were: Massachusetts, Maryland, Colorado, Vermont and Connecticut. The lowest ranking state was Mississippi, which scored just 21.01 on their scale.

The study showed some other pretty interesting findings: despite ranking at number 25 on the scale generally, California ranked highest for university quality. Meanwhile, Massachusetts had the highest number of graduate degree holders.

You can see the fully study (with imagery) here.

Source: WalletHub

Source: WalletHub